Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

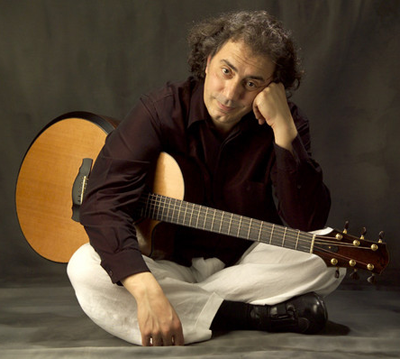

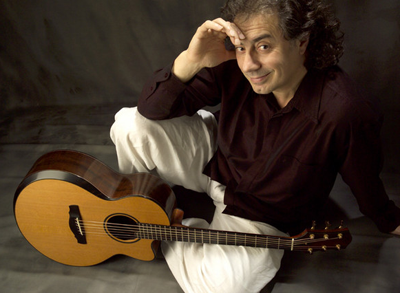

Pierre Bensusan

Servant of the Music

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1999 Anil Prasad.

There’s a lone figure standing in front of Berkeley, California’s Freight and Salvage folk club on this bright, breezy spring afternoon. Clad in a David Crosby-esque, Cherokee leather coat, the mysterious stranger knocks quietly on the venue’s entrance. Greeted only by the din of the tall, rattling door, the puzzled visitor proceeds to peer into the club’s window in search of signs of life. Innerviews, having arrived only moments before, quickly realizes the stranger is none other than renowned French acoustic guitarist Pierre Bensusan.

Bewildered at their inability to get inside on schedule, guitarist and journalist saunter to the parking lot to discuss the situation with tour manager Tom Long. Both he and Bensusan are eager to get soundcheck started. After all, with a complex, high-tech rig and an exacting approach to achieving optimal venue sound, Bensusan is far from being a ‘plug’n’play’ acoustic guitarist. Rather, he requires at least an hour of set-up time—often considerably more—before he’s satisfied.

With no club staff in sight, Bensusan and Innerviews take advantage of the down time and begin the interview festivities in the parking lot. Seated on large black and silver equipment cases in the shadow of his tour van, we begin by discussing his latest release, a compilation titled Nice Feeling. The disc draws largely from solo instrumental material from his first six studio albums which date back to the mid-‘70s. It showcases his highly-evolved virtuoso fingerstyle technique—one steeped in alternate tunings and influences that span the globe. Occasionally, the release also features pieces incorporating his distinctive wordless chanting to remind listeners that he’s also a fine vocalist with a warm, lilting tint.

"I’m very proud of this compilation," said Bensusan, 41, a native of Algeria who relocated to Paris with his parents at age 4. "Now, people who haven’t heard of me can listen to this and go ‘I heard someone else play like this, but God, he has been playing like this since 1974.’ What I like about the record is in one hour, you get a complete musical kaleidoscope of different genres. It’s world music, which I used to do for a long time before the term existed."

The record’s title is a double-entendre. Beyond the obvious interpretation, it also refers to a track inspired by his time living in the city of Nice, France in 1981. Although his music is inspired by people, places and beauty, he prefers listeners situate it in a larger framework. "It’s a about a big journey. It’s a big statement," he said, as his long, dark curly hair swayed with the wind. "I’m saying ‘This is guitar, but it isn’t about guitar. It’s about something else. So, open your ears.’ It’s a basic invitation to step into my world—my living room—and listen."

Bensusan’s first invitation was his prodigious 1975 release Près de Paris, recorded when he was only 16. Two pieces from the disc are included on Nice Feeling. Had he put the compilation together a few years ago, chances are the earlier material wouldn’t have made the cut.

"I used to be extremely harsh and intolerant with myself—especially as soon as a record would be finished," he said. "I have changed and now I can listen to any of my records and completely accept what they are, where I succeeded and where I succeeded less. It’s a bit like if the train had stopped for the first time. I can look around at the scenery—look around at my life—from a distance."

Even though Bensusan had doubts about his early efforts, it’s unlikely anyone else did. In fact, they had a significant impact on musicians and listeners across the world.

"I was amazed when I first heard Près de Paris," said Alex de Grassi, an acclaimed acoustic guitarist and long-time Bensusan listener. "His playing was very intricate and ornate, but very fluid and obviously rooted in the British Isles tradition. It was as if the baton had been passed by all my favorite British Isles folk and blues players like Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Martin Carthy and Davy Graham. It was very fresh. In subsequent recordings, Pierre's music began to show influences of North Africa, Latin America and American Jazz. I think Pierre has successfully woven these traditions into a very personal style and that's what makes him a special player. He's got a great musical vision coupled with highly-developed technique. Pierre has really pushed the technical limits of what can be done with the acoustic guitar. He's combined techniques and musical ideas in a way that stretches the imagination. His ability to phrase and ornament melodies and extended improvisations is like some of the great jazz players, and yet he uses it in the context of a solo fingerstyle approach that incorporates all the vital elements of a solo style. Pierre has shown that a wider range of music is possible in the solo guitar genre."

De Grassi’s not along in his thinking.

"Pierre’s got tremendous feeling in his music," said George Winston, the best-selling solo pianist, and a good friend of Bensusan’s. "It’s really nourishing to hear. He gets more awesome all the time. He’s put a lot of hard work into what he does. He’s just a very big inspiration to me for playing and living. He’s got a direct connection from his soul right to the instrument and it makes you want to get there more. There’s a level of soul there as much as any blues or R&B singer. Maybe more. It’s what everybody who plays music is searching for. Seeing somebody doing their thing that well makes you want to do yours that well, no matter what endeavor it is. There’s nobody I could hold in higher esteem."

There has been no shortage of accolades for Bensusan during his 25-year career. But though revered amongst guitar aficionados across North America, his work hasn’t enjoyed the profile that releases from contemporaries such as Paco de Lucia, Leo Kottke and John McLaughlin have.

"The audience here is always fantastic. So, it’s quality, not quantity. But I think there is a bigger audience for me," he said. "I don’t feel my audience is just guitarists and people into guitar music. Of course, there are a lot of different people coming to the shows, but it seems like the media and club owners put me in this pigeonhole. They are so wrong. I’m not a guitarist. I am a musician and I want to play music for people to enjoy. I want to touch them and move them to emotion. The idea is when you hear music on a guitar, you forget the instrument. You want to raise them to another level."

Bensusan is realistic about the key to transcending the "guitarist’s guitarist" tag.

"It’s about being there at the right time," he said bluntly. "I’ve started to feel that a lot of things don’t happen because of talent but because of something else—politics. I’m not very good at that. In fact, I’m very bad. Music is coming from something inside. It’s something that’s urgently needed and required. I don’t position myself. I don’t calculate. I’m 100 percent into the music."

The guitarist is considering an unusual tact in order to broaden his audience. He’s planning to take his back catalog out of print and repackage the studio material that didn’t appear on Nice Feeling into two more compilations—one containing songs and the other focusing on ensemble work.

"It’s what I should have done before—present what I have been doing in a different way that will be better accepted by radio," he explained. "I’ve been singing, playing solo tunes and performing with a group. These are a lot of different aspects of the same thing really. But for some people, it can be confusing. I have not been considering the audience’s point of view."

But why would an artist true to his muse need to consider an audience’s point of view?

"Because I haven’t been selling many records?" he asked rhetorically. "I am questioning this. Is it me? Is it the record label? Is this the music business? I would like to give a hand to people to come and listen. I think to what kind of emotion I expect when I listen to a record. I like to be in one mood for a record, so I am going to try and put all of my [vocal] songs onto a record and know that when people listen to the sequence they might see that I am a singer and that I just use the guitar as an instrument that I play very, very well. That would be kind of ironic. I would kind of like that."

Bensusan’s versatile vocal approach manifests itself in several ways on his recordings. He can be found singing songs, chanting and punctuating rhythms with Bobby McFerrin-style a cappella bursts. The unique combination came together after years of examining how best to use his voice as an extension of the guitar.

"I first played piano and I was singing all the time. So, it was always part of me. Whether I was a good or bad singer, I needed to sing," he said. "When I took up the guitar, I became even more of a singer and I even wrote a lot of songs. Then I found out I could use the guitar as an instrument to arrive at a point where the voice becomes an element of coloring. I felt very in sync with that attitude for awhile until I started to feel it was another excuse to not sing words. It was difficult to find words. I didn’t want to step into the process of systematically taking poets and their poetry, because I’ve done that a lot. It’s a good approach, but you also have to stand somewhere else. My system was to sing whatever melody and to forget that my guitar could be the singer as well. I had a system, so I broke it. Anything erected as a system is something I try to stay away from. It took me a certain amount of time to trust my guitar and ability to transcend the song and chant. So, now this is my focus—to have the guitar sing those melodies and then there is no need for a voice. So, I sing much less now, but when I sing, it’s much more dramatic. I use my voice as if I was playing with another musician. It’s a much better statement that way."

Bensusan’s use of the DADGAD alternate tuning represents a major statement to many in the guitar world. The tuning was first created by British guitarist Davy Graham in 1962 when he sought to adopt the qualities of the oud for acoustic guitar. Today, Bensusan is considered one of the world’s leading authorities on the tuning. DADGAD allows guitarists to explore tonalities and progressions free of the cliches and archetypes often associated with solo guitar music. But what does it mean for non-musicians?

"Non-musicians shouldn’t give a damn whatever tuning you are using," said a fired-up Bensusan. "A non-musician is going to just listen to the music. Thank God for that. If a non-musician starts questioning ‘What tuning do you use?’ then this is the end of the world for me. It’s like ‘Oh no! Not you! Not you too!’ I am a self-taught guitarist. No-one taught me how to tune. I was exposed to DADGAD by reading a book on alternative tunings, so I tried it and loved it. I didn’t want to use standard tuning because I would sound like other people. Initially, I was doing the most obvious things ever on DADGAD—open strings, D tonalities with a capo, E, F Sharp, and I was playing a lot of traditional music, as well as original music based on traditional inspiration like Celtic, British, American Blues, Indian and Chinese. Then I found that I was limited again. Everything I was playing was too much in the same vein. I felt it was time to take DADGAD to a different level—to make it completely disappear. I don’t want people to be distracted by this tuning. You have to play the instrument, not the tuning, otherwise you cannot deepen anything because then the guitar is playing you and you are not playing the guitar."

Bensusan also applies that philosophy to his composing process. He often waits until a piece is fully-formed in his mind before picking up the guitar to try it out.

"I have a debate with myself: ‘How do I treat this material? What do I do with it?’ It’s a long process. I feel like I’m a house builder. I start with the foundation and I build a roof, but then what do you put inside? I want my tunes to be rich, yet full of space. Suggestive, but not too vague. Precise, yet not rigid. What’s good about imagining the pieces is you have no restrictions. I try to have it pretty clear in my inner ear so that when I pick up the guitar, the guitar is going to give me other information. Sometimes it is going to confirm what I thought. Sometimes it is going to inform what I thought. And then, eventually, I take the guitar and start writing the piece. Or if I want to write something for a choir, I’m gonna do that."

In fact, Bensusan is doing just that. He’s been commissioned to create a choir work for the city of Wilton, Connecticut to be presented at the end of 2000. Last November, he also performed an original piece with a choir of 200 children in the North of France for Le Festivale Tendance.

"It took place in Boulogne-sur-Mer, just across England," said Bensusan. "This is where Napoleon brought his huge French army of 70,000 people to invade England. They had a big camp there. The field is still there. Eventually, they decided to go somewhere else and not invade England. If Napoleon had invaded England, I think the music business would be Francophone today. I like to think that. I don’t know if it’s true or not."

Although Bensusan delivered the remark lightheartedly, he admits the fact that the music business is so Anglophone dominated is of concern to Francophones.

"We have a very old culture and a language which is one of the most tremendous languages in the world—not that it is the best," said Bensusan. "There are some amazing artists expressing themselves in French, as well as those who are not using words, but music, who don’t have the recognition they deserve because they are not on the right agenda. And I think because we sing in French, we touch much less people. It’s a pity because there’s a lot of beautiful poetry, amazing ideas and amazing ways of putting things together which won’t ever be heard over here in America. The truth is, today the world is English-speaking. England has been very good at buying and selling—especially selling—all over the world. As a result, America has too."

At this point, the recently-arrived Freight and Salvage staff summon Bensusan to prepare for the show. The evening’s concert is a masterful blend of all of Bensusan’s loves: acoustic solo tunes, pieces featuring an array of electronic effects, heartfelt songs and evocative storytelling that includes the occasional French history lesson. The pieces involving electronics are particularly fascinating. Bensusan uses a volume pedal to cut the attack of notes and so he can "react like a violin with a bow." Other tools include a sophisticated multi-effects box that features reverb, overdrive, modulation, chorus, flanger and compressor. The final gadget is a digital delay, also called an echo unit, that enables him to sample himself onstage. A recent release titled Live In Paris, a duo effort with saxophonist Didier Malherbe, features tunes that showcase the vibe the Freight and Salvage audience experienced.

"What I do is loop different parts when I play live onstage," he said. "I click one pedal to open my recording and click the same pedal to shut off the recording and then create a loop of a specific length. With that length, I can add different layers and varieties of sounds, and then I appear like I am being two or three musicians. So, for a solo act like mine, it’s a very good and entertaining thing for the show as long as it’s not overdone. It’s like the cherry on the cake. It has to add something, not hide something. I also use effects to improvise—to go away from my very austere, regal behaviors to play bass, melodies and chords all at the same time. So, I can push a chord progression and feel free to fly away a bit."

The next night, Bensusan flew far away from regular gig mode. He performed an entirely acoustic concert without a P.A. at the Alliance Française auditorium in downtown San Francisco. The unplugged event was a rarity in his career. He’s only done it five times before.

"It was like day and night," he said, comparing the show to the previous evening’s performance. "Tonight, I was playing strictly acoustic. It was excellent to go back to the essence of the instrument, to react, to color the sound, to use the vibrato. When you have reverb, it’s sometimes a bit too comfortable. You have the impression that because you have reverb, you don’t have to color the actual acoustic sound. You can forget that you can do vibrato and this and that. Tonight, it was naked. It’s truth. To play for people this way was quite a challenge—a mental challenge."

And did he miss his gadgets?

"Yes. Sometimes. No. Yeah," said an uncertain Bensusan as he broke into laughter. "I was amazed because sometimes I would miss them and I would question myself ‘Why do I miss them? Because what you play is not enough?’ So, there’s interchange so I don’t have the impression something is missing. A musician has to reach and interact with whatever he has to do. Sometimes I was trying to modify the trajectory and interpretation of the sound, and the sound of my fingers as I was playing. I was very destabilized and at the same time, I tried to go back inside of me and play for myself. That was the only way I was going to succeed tonight."

Bensusan started using electronics at the very beginning of his career after playing a festival show in Vienna, Austria. He decided to take an electro-acoustic approach in order to more effectively deliver his sound to a large audience. Though his need for electronics was born of necessity, there have been critics who have charged him with relying on gimmickry.

"Maybe their criticism has been right at some point in my career," he said. "And I must say that in fact, I was overusing those effects because they were new and I was overwhelmed. It was being confronted with something new and you have to do what you have to do in order to mature. Today, I feel pretty at peace. This is something I control now. I’ve mastered it. I have a good reputation for it. But in the past, I went over the edge and maybe those people were right then. They are not right anymore."

Those with open ears agree.

"To me, it’s just part of the expression. He’s doing as much as he can as one person at one time which is more than I’ve heard anybody else do," said George Winston. "The electronics are an extension of what he does solo. He’s got so many ideas running through him and he only has two hands. I want to emphasize that he doesn’t need it. It’s what he wants."

What Bensusan wants to do next is record a new studio album. He was scheduled to release an album of solo guitar with no effects or overdubs last May. However, he became dissatisfied with last January’s Aspen, Colorado recording sessions and decided to go back to the drawing board with a new vision.

"I was not happy with the way it came out because I wrote and went straight from writing into the studio," he said. "This was wrong. I need to play the music in front of audiences first. I need the music to tell me the story. The record is still going to be only me, but there will be effects. I changed my mind. I wanted to do a solo acoustic record, but why do that? When I play, I use my effects. So, it’s going to be a mix. There will be solo guitar without effects and tunes with effects like I do onstage. It’s important to have contrast on a record. If you have several things to offer, why reduce yourself to only one?"

The forthcoming album will include a tribute to the late, pioneering acoustic guitarist Michael Hedges called "So Long Michael." Bensusan was a major inspiration for Hedges, who passed away in a car accident in 1997. Hedges even titled a piece "Bensusan" on his seminal 1984 release Aerial Boundaries.

"We had a lot of respect for each other," said Bensusan. "Michael would express it by listening to my records for three weeks in a row and then writing a piece with my name. I would express my gratitude and listen to the piece. Every time I would see him, I would tell him that I love the piece. I’ve been moved by his music on several occasions. His music has been part of me. I also have a lot of respect for his approach and attitude to the guitar. He was not imitating anyone. He was doing his thing. That’s what I care for the most. I felt very close to him because he was coming up with something very different and personal. The last time I saw him was in Buffalo, New York two years ago. He said ‘Pierre, we don’t get to see each other often enough. We really have to work together.’ I said ‘Anytime Michael.’ Then he passed away. I was in peace with him. His memory is very much alive for me."

Like Hedges, Bensusan believes there is a new discovery to be made every time he picks up the guitar.

"I’m working every day towards being a better servant of the music," he said. "I don’t think for one second that I’ve succeeded at what I do. I feel like there is so much to improve—my playing, my attention to details and how I improvise. But I feel I’ve started to really understand the language of music from the inside. With age, experience and distance, I can announce that I can really control what I want to say with the music and the emotion I want to create. I can really understand what it takes to interpret an abstraction through music and make it something I can share with people which is completely focused."

Complete Interview Transcripts:

Scene one: The Freight and Salvage folk club’s parking lot. While waiting for the club’s tardy staff to arrive, Bensusan and Innerviews take advantage of the down time to begin the interview festivities. Seated on large black and silver equipment cases in the shadow of his tour van, we begin by discussing his latest release, a compilation titled Nice Feeling.

Why is now a good time for a career retrospective?

There is no good time for a career retrospective. It’s just a matter of coincidence and opportunity. It was not something that came from me, but the French record label. They approached me with the idea of doing a guitar collection for France, so we did. I looked at all six of my records and said "This is a good tune and this is a good tune." As soon as it came out, I sent it to my friend Ricky Schultz at Zebra and he raved about it and loved it. I didn’t even think for one second to do it for America, but he said he wanted to. The feedback was tremendous. I said "The rights belong to Rounder and maybe you can discuss it with them." So, this is what happened. It works very nicely. I’m very proud of this compilation. It works fine and it’s strong. Now, people who haven’t heard of me can listen to this and enjoy it. As far as I’m concerned, it’s kind of good to resituate where I am coming from. Sometimes you need this kind of recognition so someone can hear it and go "I heard someone else play like this, but God, he has been playing like this since 1974."

Do you feel you’ve received the acclaim you deserve in North America?

No. [laughs] I mean yes and no. The audience here is always fantastic. They’re very receptive. So, it’s quality, not quantity. I feel I have a very loyal following here. These people keep coming back. But I think there is a bigger audience for me. I don’t feel my audience is just guitarists and people into guitar music. Of course, there are a lot of different people coming to the shows, but it seems like the media and club owners put me in this pigeonhole which is guitar music. They are so wrong. I mean, I’m not a guitarist. I am a musician and I want to play music for people to enjoy. I want to touch them and move them to emotion. I want to do this through music and not on the guitar. The idea is when you hear music on a guitar, you forget the instrument. You want to raise them to another level. I’m working towards that direction. I don’t think I’m doing anything wrong right now. My agent is very committed and supportive, so we’ll see.

What are some examples of acoustic guitarists you feel have transcended the "guitarist’s guitarist" category?

Paco de Lucia, Ralph Towner and Michael Hedges.

What do you think is the key to transcending the tag?

It’s about being there at the right time. I’ve started to feel that a lot of things don’t happen because of talent but because of something else—politics. I’m not very good at that. In fact, I’m very bad. [laughs] Music is coming from something inside. It’s something that’s urgently needed and required. I don’t position myself. I don’t calculate. I’m 100 percent into the music and I feel that when the quality is there, the people recognize it.

What criteria did you use when choosing the material for Nice Feeling?

Variety. Good behavior in age. If it is a good one, how did it age? It seems all those tunes are aging very well. When you think some of them are 25 years old, that’s amazing. I surprise myself. I haven’t seen my life go by since I was 17. It all seems very fresh to me today—the musicality, the playing and the sound. And even if the sound is not quite together—some of those tunes were recorded in ‘74 on four track or eight track analog machines—the criteria is musicality and the story the record was telling.

How would you describe the types of stories your records tell?

It’s about a big journey. It’s a big statement. I’m proud of this statement. I’m saying "This is guitar, but it isn’t about guitar. It’s about something else. So, open your ears. Just listen." It’s a basic invitation to step into my world—my living room—and listen.

The title Nice Feeling is a double-entendre. Describe where it came from.

I was living in Nice [France] in 1981 and I was whistling this tune for two months while I was painting my new apartment. But even though this whistling tune came about, I made the commitment to not touch my guitar until my apartment was finished. I hadn’t touched my guitar in three months. As soon as I did, "Nice Feeling" came through my fingers because it had been with me the whole time.

How do you look back at the older material from Près de Paris and Pierre Bensusan 2 that you included on the compilation?

I used to be extremely harsh and intolerant with myself—especially as soon as a record would be finished. I have changed and now I can listen to any of my records and completely accept what they are, where I succeeded and where I succeeded less. It’s a bit like if the train had stopped for the first time. I can look around at the scenery—look around at my life—from a distance. It’s very important. I can look at my life and evaluate.

Do you have a visceral feeling of your life experience being encapsulated in those pieces?

In fact, yes. This is not meant to be the case, but it does apply when you look. What I like about all this is my versatility is tremendous. I’m in awe. What I like about the record is in one hour, you get a complete musical kaleidoscope of different genres. It’s world music, which I used to do for a long time before the term existed. I used DADGAD which now everyone is writing about. Alternate tunings to me were never a big deal. It has always been there. Maybe sometimes people take advantage of that today, but I have decided not to be resentful. I am going my way and I believe in my direction.

Can you describe that direction?

It’s an even more musical direction. I’d very much like to express the music I hear inside of me. I’m working every day towards being a better servant of the music. I don’t think for one second that I’ve succeeded at what I do. I feel like there is so much to improve—my playing, my attention to details and how I improvise. But I feel I’ve started to really understand the language of music from the inside so I can be a better musician. Before, I did not think I was into it. Now, with age, experience and distance, I can announce that I can really control what I want to say with the music and the emotion I want to create. I can really understand what it takes to interpret an abstraction through music and make it something I can share with people which is completely focused.

Elaborate on the idea of being a servant to music.

I have to be. Music is stronger than you. You have to be able to compete with music. It’s a very difficult process. I have heard a lot of people who do not listen to what they play. If they did listen to what they place, they will not play what they play. I have heard many, many people! I mean, for sure they don’t listen to every note they play. There are so many notes that they could do without. It’s a matter of listening. Paco de Lucia once said something very nice and very simple. He said "The secret is how you listen." When I read that the first time, it struck me that as I am getting older, I can inhale and digest it. I can really see what he meant. It’s true. When you are a musician, before you develop your ability to be a good manual worker with your eyes, fingers and body, you have to be a listener. What is a musician? Somebody who listens. Someone who listens to things, digests their potential and then lets himself or herself be moved by it and who can then transcend that. This is a musician—somebody sensitive and always very, very apt to react fast. Someone attentive to what’s happening. Somebody who observes. It is like you are hunting the bad notes. You are hunting the spot where there is no music anymore. With musicians, when we get together, we never talk about when the music is there. We talk about when the music is not there. We discuss "Why did it happen? What did we do?" But when the music is there, we talk about something else.

I understand there’s a move afoot to take all of your old records out of print and repackage the music according to theme, style or genre.

I would like to do that. It’s what I should have done before—present what I have been doing in a different way that will be better accepted by radio. I’ve been singing, playing solo tunes and performing with a group. These are a lot of different aspects of the same thing really. But for some people, it can be confusing. I have not been considering the audience’s point of view.

Why should you?

Because I haven’t been selling many records? I am questioning this. Is it me? Is it the record label? Is it a configuration of what you do today? Is this the music business?

If you are a servant to music, why does any of this matter?

It does not matter at all. This is why I never really cared about it. But today, it starts to be important to me—not that I’ll change one note of what I do. But I might though. I would like to give a hand to people to come and listen. I think to what kind of emotion I expect when I listen to a record. I like to be in one mood for a record, so I am going to try and put all of my [vocal] songs onto a record and know that when people listen to the sequence they might see that I am a singer and that I just use the guitar as an instrument that I play very, very well. That would be kind of ironic. I would kind of like that.

It sounds like there’s a contradiction at work between the muse and the marketing.

Yeah, but it’s not like I have to do something I would not do otherwise. I am presenting what I already did in a different form. It’s still all there.

Do you not believe in the sanctity of an album as a single experience or a representation of a specific point in time?

I do, I do. But at the same time, some of those albums have been there for 25 years. How long are they going to be there? Am I a fetishist? Do I need to keep an album as a collector’s idea? What is amazing is that the life of the tune is endless. That’s what I like about it. My idea is to do now with the vocal elements and group work what we did with Nice Feeling which is a presentation of my guitarist approach in an instrumental project. The idea really worked. It’s not like I was wrong to do it. I listen to it and it has a musical strength, so it’s not like "Why did you do that?" I think the same could apply to the others, so I think we’ll do that.

So, your previous six solo studio releases will be reduced to three CDs? One vocal, one group work and one solo guitar?

Yeah, because some people don’t like it when I sing and I respect that. You know, why am I getting these people? Because they love the music. But as soon as I sing words, they tell me something that I’ve listened to. I like to listen to people tell me things. It’s not that I am going to do what they want, but I will listen. Eventually something is going to touch me which is already in me and then I react. They said "You are touching us with the music and we don’t need the words. If we want words we are going to listen to a singer whose strength, ability and experience is to interpret songs and to do what you do with music to words. When we see you, we want our minds to be free. If you use your voice without words, it’s okay. As soon as you start singing songs, you are perceived as a singer making a statement and there’s something that doesn’t follow." So, I try to understand what they meant and I realized that I was using words as music. I was saying words as I would play the notes.

Today, I don’t sing the same way I did five or ten years ago. Today, the voice is there, I am speaking to the audience, I am addressing them, but now I open my eyes. For 20 years, I was closing my eyes most of the time, especially when I would sing. My friend asked one day "Why do you close your eyes? What is it you are trying to say when you close your eyes? You don’t want us to see you? Are you shy? Are you hiding something? Do you want to hide yourself?" I said "No, it is that I am distracted when I see people." She said "It is distracting for us to never see your eyes and we wonder why we don’t." She is a comedienne and actress. So, all of these things I have started to recoup. They in fact mean the same thing. Now, I look with my eyes when I sing and I am very happy about it. I look at people and I look far away. It doesn’t mean that I am looking, but it means I am letting the feeling out to circulate and go back and forth.

Do you own your own masters?

Yeah, I do.

Describe the importance of that.

I am independent. I am free. I do whatever I want. It’s strange. I would not really mind [not owning my masters] if I was working with a good producer and record label who were really respecting my work and would never give me any fears that this could be completely abandoned. But in fact, my experience teaches me that’s not always the case. It’s better to own your own masters and to take them back whenever you feel a better opportunity will serve you more. That’s why I was very keen on owning my own masters and producing myself. And even with CBS, they allowed me to buy them back. I bought back Spices and Solilai from them. That’s why I can approach Zebra and Rounder as I did and make it work without having to ask authorization.

Do you recommend this course to young musicians prone to signing their lives away?

You never sign your life away. When you sign your life away, you are really so good that everybody wants to work with you. This is a cliché. For some very big names, the producers and record company want them to sign their lives away. In my world, no-one has ever asked me to sign my life away, even when I was with CBS Masterworks. I had a contract for five records and every record was optional. Neither they or me had to do it if we didn’t want to.

Why did your CBS Masterworks deal not work out?

I don’t know. Because they have so many artists? The people working in those majors are human beings. Like everyone else, they can only do so much. They have one project after the next. They don’t want to devote their attention for all of the time that’s necessary. They want things that are going to work in the fastest way so they can go to the next project. For someone like me, I am still developing. What I do is not obvious and I have several things to offer. It’s not easy to market a guy like me, so a smaller label is probably more appropriate.

Your last studio album was nearly five years ago. Why are you recording so sporadically?

Because I am busy. I have no time. I am touring. I have a family. I am doing work in my office. I am teaching. I am traveling. And also because it’s good to keep a wine for several years in the cellar before people drink it. So, that’s my attitude. It’s about having things to say and how you say them. But I have been writing a lot of material. There are several records I can record in one year. I going to record more now.

Let’s talk about your composition process. I understand you don’t even pick up the guitar until a piece is fully formed in your mind.

More or less, yeah. What’s good about imagining the pieces is you have no restrictions. There is nothing that can stop you from imagining whatever is going to be right for the tune. I try to have it pretty clear in my inner ear so that when I pick up the guitar, the guitar is going to give me other information. Sometimes it is going to confirm what I thought. Sometimes it is going to inform what I thought. And then, eventually, I take the guitar and start writing the piece. Or if I want to write something for a choir or string quartet, I’m gonna do that.

Are you composing for choirs and string quartets?

I’ve been writing for a children’s choir of 200 children. It’s five songs—a commission. I’ve been working with my friend Jordan Rudess on keyboards from Dixie Dregs and Dream Theater. The two us rehearsed for five days at my house in France. It was a tremendous experience. We have other projects together. He’s a musician I want to work with. He’s a very progressive musician, very open and completely a chameleon—like me. A lot of people don’t know my potential because when I play. People are really amazed. Someone the other day said "You are my favorite electric guitarist." I said "Thanks for the honor and compliment. I don’t believe what you say, but it’s nice to hear." I do some electric-sounding things with my effects. I like to create a mystery—a kind of progression, because of the way people see things and look at me. I like to surprise people. I like to say "You expect me here, but I am also here." It’s important. An artist has to show several aspects of the same art. If people are not necessarily touched here, they are going to be touched there. Aside from the choir, I’ve also been writing new material for my group.

Are there plans to record with the choir?

I would love that in fact. I would love to make a vocal project and hire a choir once in awhile. I’ve been commissioned for another choir work for the community of Wilton, Connecticut. Half of the show will be solo and the other half will be me with the choir and Jordan on keyboards. That’s going to be for the end of the year 2000.

Where was the other commission performed?

Last November at a festival in the north of France. Every year this festival commissions an artist to write a creation. It’s called Le Festivale Tendance—tendencies. It took place in Boulogne-sur-Mer, just across England. This is where Napoleon brought his huge French army of 70,000 people to invade England. They had a big camp there. The field is still there. Eventually, they decided to go somewhere else and not invade England. If Napoleon had invaded England, I think the music business would be Francophone today. I like to think that. I don’t know if it’s true or not. [laughs]

Does it concern you that the music business is so Anglophone-dominated?

It does concern Francophone people—absolutely. We have a very old culture and a language which is one of the most tremendous languages in the world—not that it is the best. But the old French has been inspiring languages like modern Italian and modern Spanish. There are some amazing artists expressing themselves in French, as well as those who are not using words, but music, who don’t have the recognition they deserve because they are not on the right agenda, you know? And I think because we sing in French, we touch much less people. It’s a pity because there’s a lot of beautiful poetry, amazing ideas and amazing ways of putting things together which won’t ever be heard over here in America. I think historically speaking, English people and the Saxon mentality is a better marketing mentality than the French mentality.

How would you describe the French mentality?

It’s a more Catholic mentality. It’s a country that’s been Catholic for a long time, so the way to do business in our country is quite different than doing business in Protestant countries because of religion and stuff. It’s quite different. Maybe in places like Germany and England, making business is the goal of a lifetime. You live to make business—to sell and buy and nothing can stop you from doing that. No human strength can persuade you that it’s wrong. But in Latin countries, it’s quite different. It’s not like we don’t business, but there are other things involved. It’s difficult to explain in English. The truth is, today the world is English-speaking. England has been very good at buying and selling—especially selling—all over the world. As a result, America is too, you know.

Can you describe the contrast with the French mentality in more depth?

The contrast is the French people are still amazed they are not ruling the world. [laughs] They haven’t digested it yet. They think they are still very important. I always like to run and think to Ireland which is a usually peaceful country, despite what we know about Irish history and the [conflicts in the] North and the South. The Republic of Ireland is peaceful and neutral. It has no trouble internationally. They do not say "We are here! We exist! We are this and we are that!" I am tired of those countries that want to be more important than the other ones. I would like people to live in gentle peace, in good cohabitation, to coexist together in a universal place that will take all of us into account and "Give peace to our children" as one of Bobby McFerrin’s songs said. We need more peace. Peace is always the bottom line. But we need to evolve and work on ourselves to live in a peaceful timeframe.

Do you consider yourself a cultural ambassador?

Maybe, yeah. I’m French. I’ve never been so French as when I’m outside my country. [laughs] I feel I represent it okay. Obviously, I am French, so people look at France through me which is pretty funny sometimes.

Speaking of Francophone culture, "Montségur" is one of the more fascinating pieces in your repertoire. Take me through how you created it.

It’s about different agendas. The first one is an improvisation in a little club in Marseilles where I found out about a guitar technique from Flamenco and Spanish classical music. From there, I went out and improvised a theme about Montségur and I started to think "Let’s go this way." What I liked about it is there was nothing guitaristical about it. In fact, a lot of what I do has nothing to do with the guitar. This is what I like about what I do—it can be played by any instrument. I try to play my instrument, I don’t want my instrument to play me. So, I focus on what I want to say in the music within the melody and try to use some classical techniques of composing such as taking a theme and playing it in a different mode and then repeating a phrase that has been heard before. But the repetition will only be the repetition of the first part. The second part will go somewhere else. You try to build a trance—something emotional which reaches a peak and still sings to dramatic elements like history, places, geography and time that happened in Montségur.

Some people in North America may not be aware of the history of Montségur during the 12th Century. Can you offer a brief history lesson?

Montségur is a castle from old France. The old Occitan language was used then which is the language of the troubadours who came from the south of France. Their heritage was from the Arabs. They were able to improvise poetry, rhymes and prose. They were very skilled. Montségur used to mean "safe mountain." There, you are not in the Pyrénées, but in an area which covers 60 kilometers where there are a lot of castles that have been built by the Cathars. The Cathars were the first protestants and refused the corruption of the church of the 12th Century. They were also refusing the authority of the Pope and criticizing the way Christianity was interpreted big time. They refused a lot of rules of the time. They were proposing something else that was very austere, obscure, orthodox and fundamentalist. This European rebellion began in Bulgaria. The first name of these people are ‘Le Bougres’—the Bulgarians in old French. Today ‘Le Bougres’ is used in the pejorative. When you say someone is a ‘Bougres.’ we are not even calling him a man. We don’t know who he is. But a lot of names come from those times.

These rebellions were first initiated in the Balkans and then all of the south of Europe including Italy and the south of France. Then It became huge all over France, but especially in the south in the Pyrénées mountains. [The Cathars] have been persecuted everywhere. They were at war against the authorities of that time—The King of France, the King of the North, the Pope, the Christian armies. It was a perfect pretext [for the Church and Northern nobility] to invade the South. From Belgium, they invaded the south of France and killed a lot of those Cathars and then went to Jerusalem and killed a lot of Jews at the same time. It was an era when Europe was trying to regain the prosperity at the end of the Roman Empire, before the barbarians completely killed everybody and tried to erase all of the good things of that time. I’m fascinated by history and especially by that era.

Is composing an easy process for you?

The inspiration is there and I feel blessed for that. I have no problem with getting the melodies and identifying them. Then, I have a debate with myself: "How do I treat this material? What do I do with it?" It’s a long process. I feel like I’m a house builder. I start with the foundation and I build a roof, but then what do you put inside? I want my tunes to be rich, yet full of space. Suggestive, but not too vague. Precise, yet not rigid. It always has to suggest or evoke something. I want the notes to be a pretext. I have to master these notes to overcome them and to have people use the notes for something else. In other words, notes are not the finality. The finality is about feelings, emotions and traveling. This is an interesting thing to talk about. I do it a lot when I teach. I try to understand and hear people when they come in with a tune. I try to make them touch what they are doing and understand how they can interact so they can take advantage of it in a better way that’s more intuitive.

How many people do you teach yearly?

I have two to four sessions, six students at a time. When I tour, I also have master classes and guitar clinics. I don’t do too many of them. I want it to be very fresh. I work with 50 to 60 people a year. That’s enough.

What are some of the basic philosophies you impart on students?

I try to respect whatever they come in with. If they ask my opinion on the artistic content, I will tell them what I feel. I also then try to analyze the parts to see where they can be split—where one part can be developed in a better way in order to evoke something else. Sometimes the tendency is to put in too many different parts and not deepen one part enough. I think it’s very important to go from an atom to create a molecule, rather than putting 26 molecules one right after the other and hope that’s going to make a good tune. You take the essential idea which contains one melody—one that has an inner reason and harmonic development potential. You can make a symphony out of three notes. That’s the little seed that blooms and becomes a big tree.

I try to ask students to go back to something very simple and minimalist and make them understand that what they play now, they should imagine they are playing in reverse. Imagine, instead of being major, you are playing it minor. Put those melodies together and it creates a new melody. Now, change the tonality. Change the mode. These are all tricks people use when they compose. I try to make them available to students as they do it. It’s a big process, because most of the people I address are self-taught guitarists who are lacking technique. So, it’s difficult for them not only to think like this, but it’s also difficult to play the ideas. I tell them "Use the technique you need. Don’t use any other technique. Use only the ingredients you need in order to express yourself. That’s all. By doing that, you will learn how to play the guitar. You don't need to play the zillions of scales or all the chords or go fast. First, identify what you want to play, then learn how to play it. It’s simple."

Do you ever encounter resistance to your methods?

Very little, but some people resist. They might leave the next day because it’s intense. Basically, you have to remain open and humble. You have to acknowledge the fact that you might have been wrong for ten years. And instead of being negative and thinking "I’ve lost me time," you can think "Well, there is something I can do better now." It’s a glass half-empty, glass half-full thing. But most of the students are very brave and courageous I must say.

What do you get out of teaching?

There is a saying that goes "Teach only what you need most to learn." I like that because it’s very true. I am teaching in order to learn. I am going back to the fundamentals. Whatever I tell them, I try to apply to me too. I try not to bullshit them. I try to be sincere in the sense that whatever I am saying to them is something I have experience with through my soul, not only my intelligence. It’s my experience of something beyond instructional intelligence which is action, attention and observation.

You mentioned the ideas of being humble, letting go of ego and learning to accept ideas. Contrast that with the idea that it takes a certain amount of ego to get onstage to do what you do.

It takes a huge amount of ego at the beginning because at the beginning, you don’t know why you go onstage. You are balanced by your ego. Maybe you have a duty and there is a reason you are there. I am there to be a servant of music. By being so, [the audience] is using me in order to elevate their soul or something. I use music for the same purpose.

The ideas of a duty beyond the tangible or being a servant to another force are usually indicative of some sort of spiritual perspective.

I think I am very religious, but only in my own way. I am not at all wearing any religious uniform. I am not fighting for any God. I respect people and I just want them to respect me. If they don’t respect me, I don’t respect them.

Scene two: Backstage after an unplugged gig at the Alliance Française auditorium in downtown San Francisco. The show was an entirely acoustic performance without a P.A.—a rarity in Bensusan’s career.

Describe the difference between tonight’s performance and yesterday’s.

It was like day and night. Tonight, I was playing strictly acoustic. It was excellent to go back to the essence of the instrument, to react, to color the sound, to use the vibrato. When you have reverb, it’s sometimes a bit too comfortable. You have the impression that because you have reverb, you don’t have to color the actual acoustic sound. You can forget that you can do vibrato and this and that. Tonight, it was naked. It’s truth. I need to do what I did tonight, but I rarely do an acoustic show—completely acoustic with no PA. I’ve maybe done this five times in my whole life. To me, the guitar is something intimate, whether it’s by myself or when I play for a very small group of people. To play for people this way was quite a challenge—a mental challenge.

Did you miss the electronics?

Yes. Sometimes. No. Yeah. [laughs] I was amazed because sometimes I would miss them and I would question myself "Why do I miss them? Because what you play is not enough?" You try to correct it immediately, so you won’t miss it. So, there’s interchange so I don’t have the impression something is missing. It’s okay. A musician has to reach and interact with whatever he has to do. So tonight, I was improvising and reaching. Sometimes I was trying to modify the trajectory and interpretation of the sound, and the sound of my fingers as I was playing. I was very destabilized and at the same time, I tried to go back inside of me and play for myself. That was the only way I was going to succeed tonight.

Describe the various stages you go through in order to electronically process acoustic guitar.

My guitar is electro-acoustic, which means I have different systems of amplifying the sound—of translating the acoustic signal into an electric signal in order to bring the guitar into the electronic world. I have two different microphones to do that. Then, with a cable, I go into the pre-amp which is going to boost that signal to get a good level in order to have a good signal ratio without any noise. With this boosted signal, I can go in my different machines. So, it’s in from one machine, into another machine and into another machine. It’s in and out, in and out. From my pre-amp, I go into a volume pedal. My right foot is always positioned on that pedal, which also helps me get balance to hold the guitar at the right height. The volume pedal also allows me to cut the attack of notes and to react like a violin with a bow to make a crescendo. It’s also good for chords. It’s a bit like an electric guitarist will play with a knob to make notes fade in and out.

From the volume pedal, I go into an equalizer which allows me to basically work the actual frequencies of my sound. It has 28 frequencies. So, my sound is divided into 28 different frequencies from very low to very high. When you play electro-acoustic guitar, you need access to these frequencies in order to cut and boost some frequencies if there are too many or not enough or if they’re non-existent or too predominant. From the equalizer, I go into a multi-effects box which gives me access to all kinds of crazy sounds and reverb—sounds like an octave bass, overdrive like an electric bass, different voicings, modulation, chorus, flanger and compressor. My final machine is a loop, which is also a digital delay. It is an echo unit. What is an echo? The ability to record and to play it again. We also call this delay. A delay is a short recording of say 200 milliseconds—much less than one second. Following that concept, you can use it as a tape recorder as well. You have 65 seconds if you want.

What I do is loop different parts when I play live onstage. I click one pedal to open my recording and click the same pedal to shut off the recording and then create a loop of a specific length. With that length, I can add different layers and varieties of sounds, and then I appear like I am being two or three musicians. So, for a solo act like mine, it’s a very good and entertaining thing for the show as long as it’s not overdone. It’s like the cherry on the cake. It has to add something, not hide something. I also use effects to improvise—to go away from my very austere, regal behaviors to play bass, melodies and chords all at the same time. So, I can push a chord progression and feel free to fly away a bit.

Why and when did you first start using electronics?

Twenty-five years ago. One day, I was working with a sound engineer at a festival in Vienna, Austria. I was playing acoustic guitar at this big festival and he asked me if I can play louder. It was so frustrating. I said "I’m very sorry, I can’t." I felt like I had nothing to do there—that I was not at the right place. [laughs] I like playing acoustic in a little room today where everyone is very receptive and attentive. But something happens to the guitar when we play the instrument for a [larger] crowd. So, I started to look around and see what was available. I started to buy magazines and equipment—everything I didn’t want to do. I wanted to stay away from that world because once you step in, you have to go further and further in order to get the purest sound. So, I guess my ear has been developing as designers have been developing and building equipment.

But amplification and tonal issues are one thing. Reverb, flange and chorus are another. What do you find fascinating about the effects?

It’s not fascinating to me. It’s an obligation. What I’m trying to do is keep my guitar as pure as ever. In doing so, I need access to the best machines—the most expensive machines. It’s not like I’m fascinated. I’m extremely curious and interested, but if I could do without it, I would. But now I’ve also developed this aspect of the sound as an extension of musical personality—an extension of my instrument.

How do you answer critics who say you’ve sold out or are trading on soulless gimmickry?

Maybe their criticism has been right at some point in my career. And I must say that in fact, I was overusing those effects because they were new and I was overwhelmed. It was being confronted with something new and you have to do what you have to do in order to mature. Today, I feel pretty at peace. I haven’t heard one criticism today. There were five or six last year. This is something I control now. I’ve mastered it. I am known for it. I have a good reputation for it. But in the past, I went over the edge and maybe those people were right then. They are not right anymore.

You’re well known in musician circles for being a prime exponent of the DADGAD tuning. Explain why that’s important in non-musician terms.

For a non-musician, DADGAD is not important. Non-musicians shouldn’t give a damn whatever tuning you are using. A non-musician is going to just listen to the music. Thank God for that. If a non-musician starts questioning "What tuning do you use?" then this is the end of the world for me, you know what I mean? It’s like "Oh no! Not you! Not you too!" [laughs] I am a self-taught guitarist. No-one taught me how to tune. I found standard tuning by myself and from talking to people at school. Then I started to fool around with mechanics and tuning heads. I was attracted to tuning the guitar differently back in ‘71 or ‘72. I was exposed to DADGAD by reading a book on alternative tunings, so I tried it and loved it. I was using all of the tunings to a point where I was not mastering any of them. I was lost. I was depending on my memories of fingering, but I was not reacting as a musician or independent artist. So, I thought I should focus on one tuning, depend on it and make it my standard tuning. I didn’t want to use standard tuning because I would sound like other people. So, I said "Okay, let’s take DADGAD and sound different and play more different musics." So, this is my focus.

Initially, I was doing the most obvious things ever on DADGAD—open strings, D tonalities with a capo, E, F Sharp, and I was playing a lot of traditional music, as well as original music based on traditional inspiration like Celtic, British, American Blues, Indian and Chinese. Then I found that I was limited again. Everything I was playing was too much in the same vein—a bit too much of the same character. I felt it was time to take DADGAD to a different level—to make it completely disappear. I don’t want people to be distracted by this tuning. I just want to play guitar, not the tuning. You have to think of it as an instrument, not a tuning. You have to play the instrument, not the tuning, otherwise you cannot deepen anything because then the guitar is playing you and you are not playing the guitar.

Describe the origins of your vocal approach.

I first played piano and I was singing all the time. So, it was always part of me. Whether I was a good or bad singer, I needed to sing. When I took up the guitar, I became even more of a singer and I even wrote a lot of songs. Then I found out I could use the guitar as an instrument to arrive at a point where the voice becomes an element of coloring. I felt very in sync with that attitude for awhile until I started to feel it was another excuse to not sing words. It was difficult to find words. I didn’t want to step into the process of systematically taking poets and their poetry, because I’ve done that a lot. It’s a good approach, but you also have to stand somewhere else. My system was to sing whatever melody and to forget that my guitar could be the singer as well. I had a system, so I broke it. Any system is bad. Anything erected as a system is something I try to stay away from.

It took me a certain amount of time to trust my guitar and ability to transcend the song and chant. So, now this is my focus—to have the guitar sing those melodies and then there is no need for a voice. So, I sing much less now, but when I sing, it’s much more dramatic. I will sing songs and use the voice to really add something musically. I use the voice as if I was playing with another musician. It’s a much better statement that way. It’s very limited compared to what another musician can do. When I play with Didier Malherbe, what he does is quite amazing behind what I sing or play. In fact, when I play with him, I hardly sing. The bird is him. He is a wind instrument and plays sax and flutes. He’s the aerial element of our duets. I am the roots and earth.

Didier is one of your most important collaborators. How did you first meet?

We met in ’81 when I was going to record Solilai. I saw Didier play with Bloom, an amazing progressive rock band he was in after Gong. We were sharing the stage at a folk-rock festival in Brittany. I became very good friends with the guitarist of the group, Yan Vagh Weinmann, who is a tremendous composer and guitar player. Jan introduced me to Didier. I told him I would love to have Didier play on my record—I can hear his lyricism on it. So, I went to see Didier and played the tunes for him and he was very happy to collaborate. So, we became very good buddies and formed a band right after that record. I played synthesizer-guitar in the band. It was four people: Didier, myself, Loy Ehrlich [keyboardist] and a percussionist named Abdou Mboup who has played with Joe Zawinul. Then I invited Didier to play in my band. We recorded Spices and toured America in a quartet. Didier also invited me to play on his record called Fetish. We always felt we should do a duet album together because we have so much together. You know it was "We should, we should." But we never had time to do it. Then, a promoter in Nottingham, England decided for us. He invited us to play at a Nottingham guitar festival. My English agent then proposed a whole tour and Didier and I did 15 concerts in England together. That was the beginning. So, you need an excuse to do those things, otherwise you will never find the time, even when people want to play together badly. Excuses must come from the official music network.

Describe the chemistry between you and Didier.

Didier is a fantastic performer. He’s very attentive to what is being played and can fit any situation. I don’t think I can be as flexible as he is. He has a very attentive sense for melody. He loves to treat and interpret the melody all the time and bring it to a level of perfection. I’m very strong on melodies too—that is an important part of what I do, so we connected right there. He is a soloist and needs someone to accompany him so he can really play. I love being that person—the one who can create an atmosphere for him to play. So, we fit very well together. We both play compositions and improvise and go off the wall.

Tell me about the new record you’re working on.

It’s going to be recorded shortly. I was demo taping in Colorado and I was not happy with the way it came out because I wrote and went straight from writing into the studio. This was wrong. I need to play the music in front of audiences first. I need the music to tell me the story.

I understand it was originally going to be a solo acoustic guitar album with no vocals and effects, but you changed your mind recently.

The record is still going to be only me, but there will be effects. I changed my mind. I wanted to do a solo acoustic record, but why do that? When I play, I use my effects. So, it’s going to be a mix. There will be solo guitar without effects and tunes with effects like I do onstage. It’s important to have contrast on a record. If you have several things to offer, why reduce yourself to only one? But the concept will be no singing. That’s a concept I have a hard time staying with, but I’m going to work hard so that I don’t sing. It’s gonna be a beautiful record.

If you want to sing, you should sing.

I do what I want to do, but it’s the story of my life—I want to play and sing and I have to stop myself from singing, at least for this record. Another project will have a lot of songs, so it’ll be quite alright. I have to consider how people might comprehend things. There is a huge audience for guitar music, so I would like them to have a record of guitar music by me.

The record will include a tune dedicated to Michael Hedges called "So long Michael." Tell me what he meant to you.

A very striking artist. I think he’s someone who could have become a very good friend, but we were too far away from each other. We had a lot of respect for each other. Michael would express it by listening to my records for three weeks in a row without discontinuing and then writing a piece with my name. ["Bensusan" from the Aerial Boundaries album]. I would express my gratitude and listen to the piece. Every time I would see him, I would tell him that I love the piece. I’ve been moved by his music on several occasions. His music has been part of me. I have a lot of respect for his approach and attitude to the guitar. He was not imitating anyone. He was doing his thing. That’s what I care for the most. I felt very close to him because he was coming up with something very different and personal. The last time I saw him was in Buffalo, New York two years ago. He said "Pierre, we don’t get to see other often enough. We really have to work together." I said "Anytime Michael." Then he passed away. I was in peace with him. His memory is very much alive.

What can you tell me about the piece itself?

I had these notes which were kind of moving to him. Sometimes notes belong to someone else. It’s like you play something but it is the energy of another that is asking you to play. A musician is a channel. So, I am like "Okay, what is it I have to play? Oh!" I felt those notes belonged to Michael’s character—the Michael mood. It’s like describing notes with an abstraction—the feel you have for the personality of someone. This is what I did when writing the song. A lot of people said they could see it. They thought of him when they listened to the music. This is exactly what I was hoping for.

You’re a Jimi Hendrix fan. I’m curious how the rock aesthetic contributes to what you do.

I don’t see rock. I don’t see acoustic. I don’t see folk. I don’t see jazz. I don’t react or think like this. So, to me, Jimi Hendrix is a phenomenal musician like Bach, like Boulez, like Joe Zawinul, like Martin Carthy. Everyone brings something which touches me. I’m a real music lover. I’m not offended by any music. My ear can be aggressed by noise. But the difference between music and noise is another chapter. When the music is quality, means something and is well interpreted, you can really focus on it. You can hear that this is a big achievement. To me, Hendrix is a painter. I associate him with impressionist painters because you can listen to Hendrix and hear a lot of interesting, not clean things. Sometimes it seems it is not together, not accomplished and not clean. Then you will listen twice or three times and think "God, it makes complete sense." The notes were an excuse to create something else that’s about feeling. To me, the Hendrix trios—bass, drums and him—were like chamber orchestras. It’s classical music because his music will survive. What is classical music? Something which never fades out.

Alex de Grassi on Pierre Bensusan

Alex de Grassi is one of the world’s most renowned fingerstyle guitarists. His latest recording is The Water Garden, released on his own label Tropo Records.

I first met Pierre when he stayed at my house in San Francisco in the early ‘80s. I think he was playing at the Great American Music Hall. We played some pieces together just for fun. I was in a standard tuning and Pierre was in DADGAD. I had already recorded using several alternate tunings, but I was amazed at how fluent he was with DADGAD. I would say "Ab7+9" and he had already found the chord. I've always found open tunings a little like getting lost in the woods, but Pierre had DADGAD down to a science. He’s learned his way around DADGAD like most people know standard tuning. Since those days, Pierre and I have played a few gigs together and shared teaching a class at The National Guitar Workshop. We last shared the stage in Denver several years ago.

I was amazed when I first heard Pierre's Près de Paris recording. His playing was very intricate and ornate, but very fluid and obviously rooted in the British Isles tradition. It was as if the baton had been passed by all my favorite British Isles folk and blues players like Bert Jansch, John Renbourn, Martin Carthy and Davy Graham. It was very fresh. In subsequent recordings, Pierre's music began to show influences of North Africa, Latin America and American Jazz. I think Pierre has successfully woven these traditions into a very personal style and that's what makes him a special player. He's got a great musical vision coupled with highly-developed technique.

Pierre has really pushed the technical limits of what can be done with the acoustic guitar. He's combined techniques and musical ideas in a way that stretches the imagination. His ability to phrase and ornament melodies and extended improvisations is like some of the great jazz players, and yet he uses it in the context of a solo fingerstyle approach that incorporates all the vital elements of a solo style. He's also got a great way of using syncopated bass lines. Pierre has shown that a wider range of music is possible in the solo guitar genre.

George Winston on Pierre Bensusan

George Winston is a Grammy-winning solo pianist and guitarist who records for Windham Hill. He’s one of the label’s pioneering artists and has released eight studio albums to date. His latest is titled Plains. Winston also runs the acclaimed Dancing Cat label which produces and promotes Hawaiian slack key guitar music.

What first comes to mind when you think about Pierre?

First, he’s got tremendous feeling in his music. Second, he’s taken the solo guitar so far. And third, he makes beautiful use of chords, chord substitutions and improvisation. I like hearing him live the best. Every time I hear him live, my own playing changes whether it’s guitar or piano. It’s really nourishing to hear. He gets more awesome all the time. He’s put a lot of hard work into what he does. He’s just a very big inspiration to me for playing and living. I love him. He’s led a full life. He’s got lots of feeling no matter what he’s doing. He’s got a great smile. It’s just like the music.

How does your playing change after you hear him live?

He’s got a direct connection from his soul right to the instrument and it makes you want to get there more. I get it occasionally, but he has it virtually all the time as far as I can see. There’s a level of soul there as much as any blues or R&B singer. Maybe more. It’s what everybody who plays music is searching for. I’ll never get there as much as he does. But it encourages me try to get to that level in my own way with what I’m doing. I don’t play much like him. I don’t use the DADGAD tuning at all, but I want to get to that level even though I never will. He’ll always be ahead of me. [laughs] It’s not about competition. It’s "Wow," you know? Seeing somebody doing their thing that well makes you want to do yours that well, no matter what endeavor it is. It doesn’t even have to be music. What’s great about listening to him is he doesn’t make me want to give up. There’s nobody I could hold in higher esteem.

You played a role in Windham Hill releasing the Early Pierre Bensusan compilation, right?

I first heard his recordings when they came out around 1976. I first saw him live in 1979. We’ve been corresponding quite a bit since sometime in the early ‘80s. I just talked about him to the folks [at Windham Hill]. I’m sure Alex de Grassi talked about him a lot too. I didn’t produce the record, but I had a lot of conversations with them. A lot of [the music business] is just serendipity. All you can do is talk about who you like or put things out yourself or put other people’s things out there and see what happens.

Pierre told Innerviews that he’d like to be perceived more as a musician, rather than as a guitarist’s guitarist. He pointed to Ralph Towner and Michael Hedges as guitarists that have transcended the latter.

I would totally agree. And I’d say there’s a real parallel to Ralph Towner. They’re completely different, but Pierre’s certainly been influenced by Ralph a little bit. It’s too bad Michael’s not alive. He would have some great things to say about Pierre. He even had a song called "Bensusan" on the Aerial Boundaries record.

What do you make of Pierres’s penchant for the world of electronics and digital effects?

He’s using less than he used to. He was using a lot more in the early ‘90s, but he’s been using things since about ’84. It’s just electricity. He doesn’t need it. To me, it’s just part of the expression. He’s doing as much as he can as one person at one time which is more than I’ve heard anybody else do. I’m not an electric player, but I can hear expression in the electric stuff with him and other people. I’ve certainly been influenced by people doing electric things. Acoustic guitar with no mic is my favorite format personally. I’m not a huge fan of electronics, but there are things I’ve heard him do which make perfect sense—like his work on the volume pedal and things like when he’ll delay a chord and improvise over it. It’s better than what a rhythm guitarist can do. I don’t know how [electronics] got so into his expression, but how he’s doing it is irrelevant which I’m sure is how he’d like a listener to feel.

Originally, his upcoming record was conceived as a solo acoustic guitar album. But he said he abandoned that idea because he wants the disc to be more representative of his many guitar approaches—acoustic or otherwise.

I’d love to hear a solo acoustic thing. The electronics are an extension of what he does solo. It all comes out of his solo thing. I can see it’s part of the same expression. He’s got so many ideas running through him and he only has two hands. And it’s tricky economically to have a band. I saw him back in ‘78 when he just miced the guitar. I’ve seen him play with a trio after the Spices record. He loves going through different phases. He started using a little electronics in ‘82. He used a lot more of them by the late ‘80s and early ‘90s. But when I saw him last year, he didn’t use the volume pedal as much. It’d be interesting to have an album of solo acoustic live just to show a different side. To me, he’s taken the solo guitar as far or farther than anyone. It’d be interesting to get that documented. If people understood what he does on solo guitar, they might understand the electronics more because they could see how he doesn’t need to do it. Rather, it’s an extension—like having a band. He’s doing exactly what he wants to do and yeah, he goes crazy with the stuff sometimes. Whoever designed this stuff makes it so you will go crazy with it, you know? Actually, I started playing on electric organ and piano for the first four years. I played until I heard Fats Waller and went "Whoa, I wanna play solo acoustic." But I’d get a new gadget like a Leslie speaker and I’d go crazy. I’d be "Whoa, let me hear everything I do strained through this." It can be fun. Certainly, what Pierre does is also very entertaining live. But I want to emphasize that he doesn’t need it, it’s what he wants.

What do you believe audiences take away from a Bensusan concert?

I’ve seen him perform probably 20 times. I think everybody is moved and amazed as far as I can tell. I’m so busy dealing with my own being moved and amazement that I’m not really conscious of it. When I go hear somebody play, nothing else exists. I don’t go with anybody. It’s the most unsociable three hours imaginable for me. It’s not a social calling. It’s education and nourishment. Pierre certainly provides that. You’re going to hear something different every time. You could follow him around on a tour and hear different things different nights. For instance, he does a great "Night in Tunisia" and an Irish thing with four or five tunes. There’s an African thing too.

What influence do you think he’s had on the acoustic guitar world at large?

I think he’s encouraged people to explore DADGAD more, as well as improvisation in solo guitar. He’s sped up the evolution of the form.

What’s your favorite album?

My personal favorite is Solilai. I like ‘em all, but that’s my very favorite from beginning to end. It’s like one big, amazing song. When I know an artist that well, it’s not "What do I like?" but "What are they doing now? What is the expression now?"

I hear you’re diving further into the acoustic guitar world yourself lately. You’ve done a number of guitar-only shows this year and the limited edition version of Plains contains two solo guitar bonus tracks.