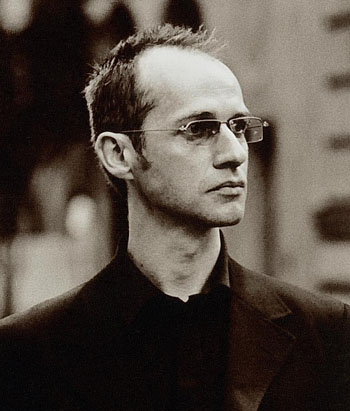

Iarla Ó Lionáird

Elastic Traditions

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2000 Anil Prasad.

I always felt that although traditional music was a wonderful birthright given to me, it was also an imprisoning one," says Irish singer-songwriter Iarla Ó Lionáird. "You have to make strong decisions if you want to do anything other than that. You have to step outside the fold."

As the lead vocalist for Afro Celt Sound System, Ó Lionáird knows more than a thing or two about bending musical conventions. Indeed, the band’s one-of-a-kind, seamless, high-energy mesh of West African, Irish and electronica elements has received enormous praise since debuting in 1995. Ó Lionáird’s lush, wistful voice represents the eye of the band’s hurricane of sound.

Ó Lionáird is justifiably proud of his contribution to the Afro Celts, but he’s far from abandoned his roots in traditional Irish music. In fact, he’s revered as one of Ireland’s foremost singers of sean-no or "old time" music. To this day, the native of Cuil Aodha, a Gaelic-speaking village, continues performing as a solo vocalist during his time off from the band.

His latest solo CD I Could Read The Sky is a soundtrack for a movie version of Timothy O’Grady’s novel of the same name. It’s a fictional work that looks at the story of a musical Irishman who emigrates to England in search of employment, love and stability unavailable to him in his homeland. What he finds instead is a reality steeped in sorrow. Yet through his bleak existence, he takes solace in music—a temporary respite from his downward spiral. It’s a rich effort, full of intriguing, finely-etched imagery that derives as much from Chicago-born O’Grady’s evocative approach as it does from the impressive pictorial contributions courtesy of British photographer Steve Pyke.

Many of the same terms apply to Ó Lionáird’s soundtrack. Its diverse palette of sounds chronicle the protagonist’s journey via the elegant simplicity of traditional fiddle and guitar tunes to stark spoken word pieces to intricate textures and pulsing beats—often anchored by Ó Lionáird's poignant vocals. Some of the talent joining him on the release include fiddler Martin Hayes, guitarist Dennis Cahill and vocalist Sinead O’Connor.

Ó Lionáird took Innerviews through a detailed examination of the making of the soundtrack. He also offers an intriguing perspective on the necessity of an elastic approach to tradition, as well as a look at the inner workings of the Afro Celts.

What initially drew you to the book and script?

It’s a beautiful book and its story was fascinating to me. And before the book, I knew the photographer Steve Pyke very well. I’d seen a lot of his photographs. Then the book came out and I met Tim O’Grady. I loved the book. It was very interesting, kind of magical and full of references to music. It was an imaginary trawl of the mind—of the Irish man abroad. It was quite experimental, rather than an epic story like Angela’s Ashes—that attracted me to it as well. I didn’t know they were going to make a movie based on it. But the producers approached me and asked if I’d like to sing for the movie. I said "I’d like to do the music for the whole lot." So, they thought about that and came back and said okay. But I was attracted to the story from the get go and thought I could bring something to it because I’m an Irishman and because I had met a lot of people who had the emigrant experience—in London particularly, as well as through music. I met a lot of people over there—a generation who were older and had sons and daughters, many of whom are musicians. So, the theme of the book didn’t seem very strange if you grew up in Ireland in the ‘50s, ‘70s or ‘80s. You get well used to the concept of people leaving and finding work and a life somewhere else, which is essentially what was going on all the time.

Do you have any first-hand experience with the emigrant dilemma as well?

I didn’t really. I was lucky. That’s the funny thing about it. The only thing that happened to me was I moved from a very rural part of Ireland to the city which was a huge change for me. But I didn’t really encounter the emigrant experience to Britain first-hand until I went to London working as a musician. That was pretty profound. You kind of saw first-hand the fracturing and the upset. Of course, there’s some huge success as well, but there was such a visible amount of poverty and fallout from the whole experience. I felt the ghettoization and a sadness to do with the communities having to move to a country where although they got work, they were treated like outsiders. In many ways, they were like a serf class and the book bore that out. That’s very much the theme of the book—that you can go to a place like England having had such a poor existence, but nonetheless an existence that made some sense culturally. In England, everything you understood in Ireland was of little use to you in this new world. Your skills didn’t match the new reality, so automatically you were at the bottom of the pile. So, it was pretty obvious to me the first time I worked in London. Even today, you can see traces of it.

Describe the general contrast the Irish emigrants experienced.

I think the Irish people at that time went there for work and economic reasons. But if they’re anything like the people I grew up with, they didn’t really have much knowledge of money or material. They would have been very religious, simple kinds of people who were more interested in stories, music, folklore, folk tales, old sayings, and family than in the rules of the commercial world. I don’t think they would have had any education in that either through lifestyle or schooling. They would have been experts at fishing salmon out of a river with their bare hands or tending to a pair of horses in a field. It sounds odd, but the book talks about finding it strange to buy a bus ticket or getting lost in a city quite easily. It’s almost like a different mindset. The book is excellent in how it talks about that.

You’ve said you weren’t particularly prepared for the soundtrack process going into it. What were the key challenges you faced?

I had never done anything like it before. So, in a way I was ill-prepared, but in other ways I was quite well-prepared because I’m used to making music. In some ways, it’s easier than making music for albums because you have a script to follow and an emotional story to explore. If you use that to your advantage, it’s a very strong guide to the mood you’re trying to create. I found it very exciting. Plus the movie wasn’t really available for us to look at during much of the construction of the soundtrack. We were working off the script and cue sheets—just a list of key points and scenes that require being lifted out using music. There might have been 40 of them in the entire movie. You also set out to create recurring themes as well. The movie is full of recurring events. It’s very much based on flashback. The main character keeps remembering certain things that happened. So, I found it a fascinating exercise. It was technically challenging towards the end. Both myself and Ron Aslan who worked on it with me, didn’t really have experience mixing to a 5.1 ratio which is a very different sound picture than we’re used to. But otherwise, we used the same tools and machines we normally use and tried to involve an interesting palette of sounds and instruments to give it an Irish feel, yet give it a modern urban feel as well.

How tricky was it to create the music and then map it back to the visuals after the fact?

I know a lot of people would say that it would be difficult, but it was amazing that it worked out so well. When we laid down the music for the picture the first time, I remember the extraordinary feeling I had. I’ll never forget seeing the picture come alive with this other musical language weaving into the images. We didn’t have much trouble with it. Obviously, some things had to be tweaked and there were different directions, themes and pieces. The director had a lot to do with picking the final ones and that’s pretty normal I understand. That was a different thing as well—working with a director and learning to fall in with that discipline of not having the final say.

Given the absence of footage while composing, your background in traditional Irish culture must have been a significant advantage.

It was surely a tremendous help. That’s the only reason I chose to do the movie in the first place. I felt I could straddle both ends of stick, much as the movie does. It deals with people who come from a certain background going into a much more complex background like going from a country to a city. I felt I could make that migration in music because I started out in traditional songs and ended up doing complex modern music with the Afro Celts and other people. It felt natural to adopt the strategy I adopted and this is what I offered the movie people when we first spoke about it. I fully intended to use electronica textures and native Irish instruments like concertinas, bodhráns and fiddles, as well as all the drones and other sounds. They all built up in a layering, textural process—a weave if you like.

You believe music has a shape and color. I imagine that took on new meaning for you within the context of this soundtrack.

It did. In this case, they were dark colors, predominantly. Sometimes, I think the movie is a very emotional, tough thing to watch. So, the music had to speak that language. One of the great pleasures I had during the whole thing musically was working with Martin Hayes [fiddle] and Dennis Cahill [guitar and mandolin] who live in Seattle. I think Martin’s track "Mother" is a very potent, improvisational fiddle piece. It’s very pure, simple and straw-colored. So there’s a lot of contrast on the soundtrack where you have heavy, dense, complex pieces and then it strips down to something very simple like an individual sound or a simple fiddle tune.

One of the movie’s main themes is the idea of music being the one thing that enables the main character to salvage himself from his existence—it was what kept him together. I imagine it’s an idea you can relate to.

Very much so. Music is special to the movie and the book in those terms. It’s the one thread in the man’s life that kept him together and motivated, and in some ways coherent as a person when everything else is falling down around him. In some ways, it’s his prison as well. I don’t think the movie reflects that side, but I feel a lot of Irish people who went aboard—to England in particular—tended to ghettoize themselves. When you hold on to your traditions too much in a foreign land, you become ghettoized. Yet you feel you must hold on to them in order to feel secure and happy, and to make sense of yourself culturally. So, there’s no answer for that crux, irony or paradox. But I could relate to it very much through my own background. I always felt that although traditional music was a wonderful birthright given to me, it was also an imprisoning one. You have to make strong decisions if you want to do anything other than that. You have to step outside the fold.

Expand on what you mean by traditional music being imprisoning.

Tradition goes two ways. I thought about it while working on the movie often. Again, I don’t think it explores it quite as much as the book, but it does indirectly. It exposes the truism that if you go to a new reality and stick to your guns, it’ll keep you together. But it will keep you as you were. It won’t allow you to change. To change, you have to give to tradition. You have to lend it the odd thing. The odd thing about all of this is that the most original forms of Irish music, specifically fiddle playing, available on record today wasn’t first recorded in Ireland. It was recorded in America. It came back to Ireland from America through Michael Coleman in the 1920s. They [Irish immigrants in America] held onto the tradition much more strongly, simply because they felt themselves in a situation of seclusion. They needed to protect themselves with a sort of cultural barrier. So, musical culture takes on a very strengthened, hyper-realistic dimension when it’s abroad sometimes. It tends to be stronger in the minds of people who purvey it there than even with the people at home.

Tell me about the spiritual themes you explored while composing for the movie.

Even reading the record sleeve, you’ll know that as the process progressed, it became more and more about my own musical story as well, in a sense. It was reflecting my own upbringing—not in a nostalgic way, but in a responsive way. It was just dreaming away, back to the kind of reality that I grew up with, which was very Catholic and sometimes Catholic mixed with pre-Christian. Where I grew up, there’s a lot patron saints which a lot of people say were actually Pagan and pre-Christian. There’s a lot of ritualistic, cultural, religious behavior in the parts I grew up in. It was just luck that the movie needed prayerful themes and meditative sequences. I found it fascinating in a way and it was an indulgence I suppose. Some people have criticized me for it, but sometimes they don’t realize that there is a menu when you do a soundtrack. The director has a menu and you have to cook the food. I was glad to. Whereas it looks like an indulgence, it was what I was asked to do. But in doing so, I was exploring my own world and background. So you have tracks like "Prayer" and "Grace/Grásta Dé" which yearn back to another time in my life.

What did you learn about your own strengths and weaknesses during the process?

That I have very definite limitations on the instrumental front. I played some piano and stuff on it, but I think next time I’d get someone else to play those. But in confronting one’s limitations, one also finds one’s possibilities. You can always get better at something if you practice and try things out. This was the first recording project in which I was very heavily involved in the technical musical process to the extent where I played a lot of the instruments, was involved in quite a lot of synthesis, and in all of the production detail, decision-making and tweaking. It was a privileged position to be in. I was able to create something from the ground up. That’s not to say I did everything, but I was involved in every single facet. So yeah, I found some limitations, but limitations are good. The most interesting music comes out of one’s limitations I think. There are a thousand different takes one could do on some things, especially when you’ve lived with something for a long time. Also, one of the things that happens when you do a soundtrack is you’re under a lot of time pressure. Most people are when they work. It’s a natural thing and one that’s a motivator, but sometimes you listen to a track a month after you finish it and you think "Oh well. I wish I had done this or that to this track." It’s nothing major, but sometimes small things matter to people, especially for musicians. As for strengths, that’s for other people to judge. I wouldn’t want to comment on that other than say I did my best at the time. There are lots of excuses people make for not doing something better, but at the end of the day, it is what it is and I’m reasonably happy with it.

What evolution does your music for I Could Read the Sky represent from your first solo album Seven Steps to Mercy?

I think there is an evolution. In some ways, I was using the soundtrack as an exploratory palette for myself in as much as I had to provide the music, but I was also using it as a means of exploration for my own benefit in terms of getting more experience in the studio, trying out new strategies and creating moods. It was more organic in some ways than the first album, which Michael Brook produced. I think there’s less finesse as well. But sometimes I missed his expertise in honing things down. He’s really a master of that.

How did your previous work with Brook influence your approach to the soundtrack?

A lot of the collage effects and sounds you find on this record are similar to what I did on the record with Michael. So, in a way I carried forward in many respects. The record turned out to be an exploration of my youth growing up in a sort of Gaelic cultural bubble. I tried to explore that reality on the record. It’s something you could explore forever really. I think I went further with It this time. There’s maybe more variety on this one too because obviously I’m not the only one singing on it.

You once said "I don’t have to go down the paths that other people other than Real World would carve out for me." What A&R influence does Real World have on your output?

Very little really. I’m allowed to do what I want to do pretty much—within reason. I mean, there are always budgetary restrictions and that’s a reality for any recording artist big or small. Real World is a small record label. They don’t have the most meaty budgets, but they give me a tremendous amount of freedom and that’s what I’ve found favorable. They give me a great deal of support—not just financial, but emotional. They’re interested in what I do and as long as they are, that’s all I want really. They allow me to expand my horizons and try out different things. I wouldn’t want to make the same kind of record every time. That would be a waste of my time. So, they don’t really intrude negatively.

I’m pretty open to other people’s views. One has to remember that even on this record, I brought in Dave Bottrill to mix it. He’s produced and mixed records for Peter Gabriel. I found him tremendously helpful and both the record company and I decided that he would be a great man to help me out. So, it was a joint decision at the mix stage. Quite a lot of things happened as a result. I felt I was further enabled by his skill to do different things. For example, "Stretched On Your Grave" was completely changed in the mix stage. The melody was changed and it became a new kind of song. I’m glad the record company voiced their view, which happened to concur with mine. Obviously, they don’t always concur, but I’m glad on this project there was quite a bit of concurrent thinking.

I understand the first Afro Celts album, Sound Magic, wasn’t your initial foray out of traditional Irish music.

I had dabbled with a few guys, but the Afro Celts was pretty much the first serious foray. Before the Afro Celts, I had done some writing with a guy in Dublin on a project called Technogue. That’s a great name, isn’t it? [laughs] It’s like mixing the Pogues with techno. That was good because it sharpened up my writing and made me ready to do it with the Afro Celts. With the Afro Celts, I had never had anyone provide as much to me beforehand. What they provided to me as substrate for songs was excellent. It’s quite inspirational and it’s still that way. I still depend on the band for creating the proper context for me to actually come in and do something.

When you did the first album, how did you initially deal with the chasm between your traditional leanings and what Simon Emmerson was trying to achieve?

To be honest, it didn’t feel like a chasm. This is the reason why the Afro Celts happened. I felt very comfortable with it. They really loved what I did and it was almost as if it was exactly what they were looking for, even though they didn’t know what they were looking for. To me, there is a huge degree of compatibility and satisfaction with the kind of work we’re jointly creating. There was a lot of comfort with it. In some ways, Release, the second album, was more challenging in that I had to develop new ways of singing and strategies, because I wouldn’t want the Afro Celts to be easy for me. There would be no point in it otherwise, because I still do lots of solo gigs all over the world. America is the only place I haven’t done it yet. I’ve been doing a very interesting multimedia show this summer with very old songs and huge images. But to get back to the Afro Celts, with them, I kind of expect to be challenged to bring out something different in myself both in technique and overall approach. I think that’s good.

You’re in the midst of recording the third Afro Celts record. What can you tell me about it?

It’s going very well. It’s been going on now for two or three months. There’s another two months left I’d say. It’s complex and more daring than the last one I think. We haven’t mixed a single track yet, but there are moments where it’s much bigger. And there are other tracks that have a very folk sound as well—not just electronic. Obviously, there are tracks that are very, very electronic. I think we’re going further down each avenue than we did before, to put it generally. Where we want something to sound folky, it sounds very folky. Where we want something to sound very electronic, we go very far down that road. There are also a lot of really beautiful African vocals this time. Perhaps we weren’t as strong on that last time. There are also some different instruments brought in for the first time.

The more I think about it, the more I think the last album was very constantly coming at you. Maybe that was out of fear that we wouldn’t get it right. We’ve got a lot more tracks going on this time—two times as many. We have more choice, so I hope the album will turn out to be bigger in scale where we want it to be, but also smaller and more intimate where we want it to be. I think it takes a certain confidence to do that. I hope we have it this time. I think we will. It’s shaping up very well. It’s been a very interesting, harmonious and lovely experience making it.

I’m told the album also features a deeper exploration of Gaelic culture than the previous records.

It’s a deeper exploration of everything really. We’ve had a lot more time to turn it around than the last album. And we haven’t had the fracturing episode of Jo Bruce's death. Jo was our wonderful keyboardist and friend. He passed away in 1997 during the making of the last record from an asthma attack. From a production point of view, that slowed things down and squashed us into a situation in which we had to make the most out of fewer tracks. We were pleased with the result, but I hope this upcoming album is richer, more varied, more subtle and inherently more effective at the end of the day.

The first Afro Celts album was a landmark achievement. It changed many people’s ideas of how different musics can be bridged. That must have created enormous pressure on the band when it came time to make the follow-up.

It did. I think we reacted to it fearfully. I would say we tried to pack everything into every track—maybe too much. I don’t like to be critical of the record, but there’s no harm in it either. We’re critical in private, otherwise we wouldn’t have to go on and make another one. We keep trying to improve all the time. I think the second record was in some ways overly structured and not breathing out enough. I think we could do better, you know? We tried to learn the lessons of the first record for the upcoming one as well. We’re very cognizant of the fact that people say we made a landmark record on record one. It’s possibly impossible to make another landmark record. But we’re trying to incorporate some of the aspects of the naïveté of the first album into this one.

Some have argued the second album mined too much of the same territory as the first.

Maybe it did. I think we tried to push things as well. For example, I think the fast tunes on the second record were superb. They were hard and edgy. I think "Lovers of Light" was a breakthrough in terms of a contemporary mix. It’s either a love it or hate it kind of track. I thought it was a real achievement in giving something a really brilliant edge and still having it identifiable as an Irish tune. I think it was far ahead of anything that was around at the time. I think some aspects of the new record are going to be more mellow—more "lovin’ it," you know? I hope so. The first record was very much like that for me—more "lovin’ it" and more peace.

I’ve been hearing Afro Celts music in a couple of American television advertisements lately.

That’s right, yeah. These big corporate giants like Ford and Visa seem to like us, believe it or not. I haven’t seen them myself, but I know they’ve happened.

What do you make of the decision to let them use the material?

I’ve got nothing against Ford or Visa. I don’t drive a Ford, but I do have a Visa card. They were looking for music and our publishing company sold it to them—simple as that. A lot of musicians do this, don’t they? I mean, look at Moby. You can hardly turn on the TV or radio without having Moby on. I don’t read too much into it. If it was something we didn’t like, we wouldn’t do them. There have been certain people who have tried to buy our music and we haven’t agreed to it on the basis of various things usually to do with Third World exploitation. You can argue that Ford are car makers and are damaging the environment. I’m not going to argue that one, but I’ve got a car and I like driving it. [laughs] Does that surprise you?

Not at all. With the narrow focus of radio and the music press these days, it’s understandable for bands to leverage as many outlets as possible to publicize their work.

You know, there’s probably a constituency out there that buys Afro Celts music and thinks it's very green and this, that or the other. And we are. But in the case of Visa and Ford, I thought there was nothing wrong with it. Why not? It’s a source of income for us which we desperately need. We find it difficult to make money on tours and we’re very much in demand as a live band. But it’s still hard to make it pay. There are quite a lot of us in the band. It’s a struggle sometimes to make the books balance out. I suppose if we were bigger, we could be even more scrutinizing.

When you sell a piece of music to an ad agency or whatever, you don’t really have any control over what the ad’s going to look like. Obviously, if there was anything untoward in it that we didn’t like, we’d make it quite clear. We’ve sold music to films as well. The Stigmata soundtrack had a song by us—the Sinead O’Connor track "Release." I’m sure the record label wanted to do that because it gave us great exposure and that in turn helps bring us to the people that want to hear us. If we don’t do things like that, it becomes more difficult to move forward and actually play the places we want to play—primarily America. It’s extremely expensive touring America. We really love doing it, so we have to find ways to make it work.

Sheila Chandra told Innerviews "The thing about your singing voice is that you can’t lie with it. If you’re crying, laughing or having an off day, it will show in the tone of your voice. I think there’s something very concretely special and truthful about singing." What’s your perspective?

I have tremendous regard for Sheila. I know her quite well and I agree with her. There’s some truth. Singing is a very physical act. I think if you are approaching a song, particularly in a live context—but in the studio as well—you need to be in good form from a functional point of view to get a good job done. But your emotions will usually percolate through as well. It can be good to be in bad form. [laughs] It can be beneficial to the project. It’s very difficult to lie with your voice. The voice is a part of the human being, more so than with most instruments. The voice is very strongly associated with your whole being and emotional structure. That’s the power of it. That’s why even if it’s sounding blue sometimes, it’s still worth listening to because it’s real.

Every artist, whether they’re a singer or a musician, has a performance that’s less than completely truthful. There’s an element of artifice involved in every art form where you have to project your feelings beyond yourself. That’s automatically setting up a mask or artificial structure. But behind that, there still can be a performance with a certain truth and emotional value to it. It’s an interesting question: Why do people go to hear people sing at all? It’s not just because they like the tune. I think if you reflect on singers like Billie Holiday, it’s also to reflect on the pain they’re going through. The truth of their experience—and everyone else’s—is very complex. We’re human beings. You might know more about someone from hearing them sing, rather than talking to them, depending on how they carry it off. It reveals something about people at its best. But that doesn’t apply to singers like those on the pop charts.

In Western culture, very few people sing anymore. For the most part, we look to other people instead of ourselves for that expression. Do you feel something’s been lost along the way?

I think something has been lost. In the world of traditional Irish music I come from, the great thing is everybody was singing and playing. There was no big deal. There was no such thing as a great singer or bad singer. Everybody had their own voice. You could go to the pub and this fellow would sing a song more than any other and another person would sing another song more than any other. It was their song. But now it’s all become very businesslike. The music business end is something one could spend a lot of time criticizing. There’s some amazing music out there for sure and we’re lucky to have it. But there’s an awful lot that’s really not of much value really. It’s just a way of making money. The idea of music as community is becoming less prevalent worldwide, I’d say. It started as people began realizing that it’s a commodity. The odd thing is that I’m a singer and my wife can sing too. But she sings a lot less than me. Maybe that’s proof as well. There’s something insidious about the professionalism of music-making. [laughs]

Your greatest passion lies in using your skills as a vocalist first and musician second. But you’ve also said that you’re more interested in musical revelation than lyrical revelation. Where do those two ideas meet for you?

I have time for everything. For instance, Bob Dylan’s revelation is always lyrical to me, not just musical. It’s a combination of both. Bob Dylan without his lyrics would be far less interesting, wouldn’t it? I always operate on the basis that no-one ever understood what I was singing about for the most part because I sing in Gaelic. So, I always asked myself "Why are people coming to my concerts and buying my records?" And it’s simply because they’re hearing something else. So, I’ve tended to lean towards the music and what it can say regardless of the words, almost. It’s funny, at a recent concert, someone suggested I should dispense of words altogether. [laughs] I’d never do that though. The words and poetry of the old Gaelic songs that I sing are something I also aspire to in my own work. That simplicity and brevity is something I try to bring to the Afro Celts as well. I don’t set out to write a big sexy rock song. That’s not to say I’m not interested in all kinds of music, because I am. So, it’s music that turns me on more than lyrics do these days. The sound of the voice is like a carrier wave. It carries both words and emotion. That’s what interests me.