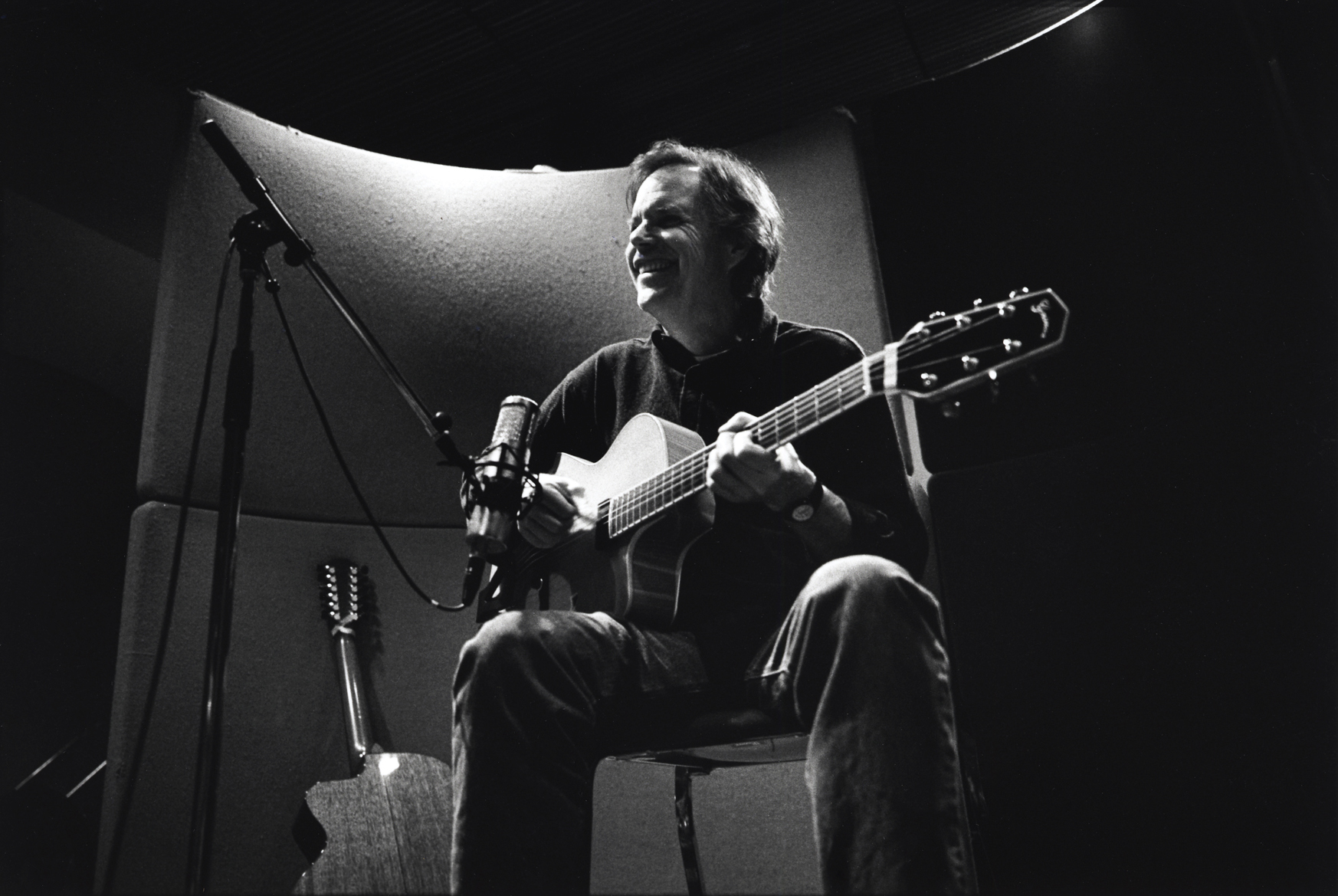

Leo Kottke

Duo Dialogues

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2006 Anil Prasad.

Photo: RCA Victor

Photo: RCA Victor

Leo Kottke's virtuoso fingerstyle steel-string guitar work communicates a broad range of emotions via a singular blend of tonal colors, percussive elements, and infectious rhythms. His singer-songwriter efforts—delivered with his rumbling, baritone voice—have also yielded dozens of idiosyncratic and endearing songs. His concert banter, infused with hilarious and illuminating tales, is equally legendary.

Kottke’s career took flight during the late ’60s when he signed to John Fahey’s Takoma Records label and went on to record 6- and 12-String Guitar, one of the most influential solo acoustic guitar records ever released. With hundreds of thousands of copies sold, the 1969 album propelled Kottke into the spotlight. He went on to record for Capitol and Chrysalis during the ’70s and early ’80s—stints that found him showing up in the Billboard charts and mainstream media worldwide. However, Kottke refused to let fame betray his muse and ensured that his rootsy approach—one that explores the intersections between folk, jazz, and classical music—remained intact.

Since the mid-’80s, Kottke has augmented his solo bent with several eclectic collaborative records that take his rollicking instrumentals, meditative tunes, and quirky songs, and situate them in contexts as diverse as chamber music, pop, funk, and hip-hop. But the most significant joint endeavors of his career are found on his recent pairings with Phish bassist Mike Gordon. The duo has released two records to date: 2002’s Clone and their latest, Sixty Six Steps.

The new recording was helmed by producer David Z, known for his work with Prince and Jonny Lang. It also features drummer Neil Symonette, the house drummer at Compass Point Studios in Nassau where the album was recorded. The influence of Symonette and the locale itself made for a record that was subtly colored by calypso influences. But it’s Kottke and Gordon’s impressive virtuoso interplay that is at the center of the album. On their original compositions, as well as on intriguing covers including Aerosmith’s “Sweet Emotion” and Fleetwood Mac’s “Oh Well,” the two gleefully imbibe in their infectiously playful chemistry.

How do you and Mike work together to write and arrange pieces?

We sit down, goof around, and throw ideas at each other and inevitably, something will get a little traction. There’s nothing really deliberate about what either of us does. Ideas pop up mutually and independently and we run with them. Mike and I have really become one thing and there’s no subdivision within that thing. It’s a great experience to play with him. We got to know each other before we ever played together. I think if you can get along, you can usually work together. If you can’t get along, why bother? The issue with me is that I’m a hog and when I play with anyone, I typically get in everyone’s way in different ways, according to the rules of whatever instrument they play. So, Mike and I talked about having him play bass beyond its usual role, rather than playing the two, the four, and the roots. It makes things easier for both of us. As a result, we don’t collide very often. In effect, the bass has become a horn in this collaboration. Mike is able to do anything he wants and I get to try to keep up.

Describe how the new album’s calypso elements relate back to when you first picked up the guitar.

Mike said he heard some calypso feel in my stuff and that reminded me that it really is in there. So, he thought it would be a good idea to go somewhere where calypso happened, like the Bahamas. We weren’t intending by any stretch to make a record with a calypso feel, but it’s hard not to feel that calypso thing when you’re working with Neil Symonette, who was born and raised in Nassau. It’s natural that what we did was imbued with some of that. Calypso was something I forgot about before those sessions. When I was learning to play the guitar, I tried to find calypso recordings and failed. All I can remember is hearing some calypso on a couple of radio stations once. What I like about calypso is the rhythmic structure and the way the melody moves around within that. It has a real bounce. John Fahey once said “Music is to dance to. If you don’t have the dance happening, you might as well forget about it.” I think that’s probably true.

When I started playing, I was also drawn to Buddy Holly. There’s a solo in “Cryin’, Waitin’, Hopin’” that sounds dead simple, but try and play it yourself so it means something. You can’t. It was a special moment that was caught. Now, that track didn’t remotely resemble calypso, but it had a calypso nature, with a diatonic, major-third melodic approach. So calypso was out there as a cloud on my horizon that cast a shadow on my development. I was trying to find that rhythmic sense on our version of Pete Seeger’s “Living In The Country” on the new record. It represented Pete’s idea of calypso. I love the piece because of the way it adds and drops beats. It has that rolling, propulsive, catchy thing that calypso has.

Your main instruments on the album are your Taylor Leo Kottke Signature 6- and 12-string guitars. What modifications have you made to them?

I’ve made the same modifications to every guitar I’ve owned. For me, they always have the strings too high in the nut. Guitar makers have some rule of thumb they use to determine how high they should be and I don’t think it works. My idea is that the strings should be no higher in the nut than if you had the zero fret there. So, I lower them. They also almost always have the spacing too narrow on the nut. Apparently, they move everything in so nobody will fall off the fretboard when they’re fretting. But if you do that, you’re just not fretting right. I like to have a little room, so I change the nut too. They also have this habit of lowering the high E at the saddle and it’s always too low for me. To compensate, I get a new saddle cut and have the low E come up. Frequently, I’ll have the B come up too. Another reason I change the saddle is because I prefer bone.

You use a Del Vecchio resonator on “The Grid.” Why did you switch guitars for that track?

I was having trouble with “The Grid,” and when the guitar player is having trouble, we get him out of the building and put some food in him. Then the guitar player would come back and frequently his approach was completely different. I don’t know who this guy is that turns up at the last minute with a different approach. When I got back from the restaurant, I also asked the studio owner if he had a Del Vecchio and he did. It was a wreck. The neck was warped and the strings were rusty and dead. It was like playing bananas that had been lying out in the sun. One of my regrets on the record is you can hear the rust and the fact that something is wrong with the guitar. But you can also hear that beautiful Del Vecchio quality. Half of what I’m playing on that track is an attempt to not hurt myself. You can do that with rusty strings. It was a really dangerous guitar to play.

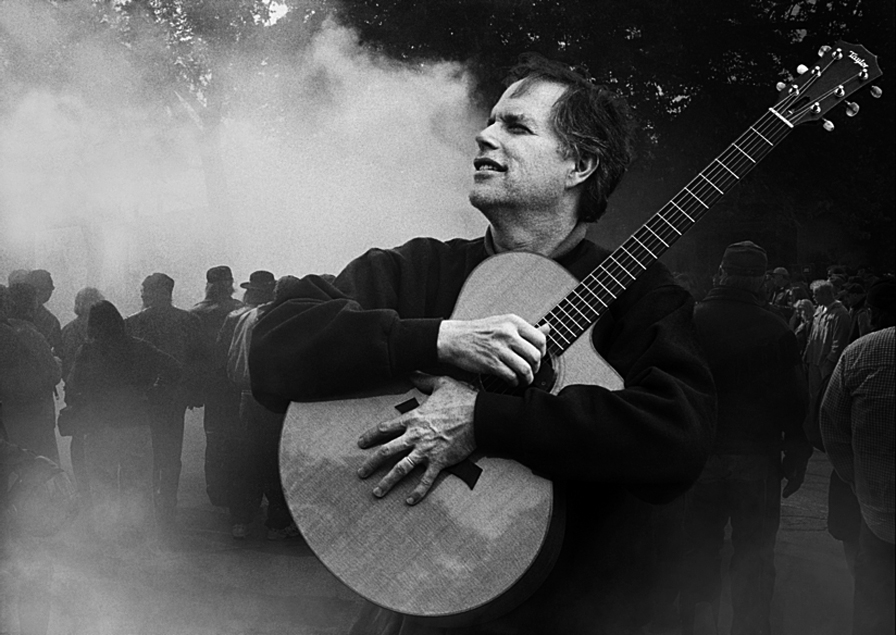

Photo: RCA Victor

Photo: RCA Victor

Your preference is to leave fret noise in your recordings. Why?

When I first started out, I didn’t know there was anything you could do about that stuff. When I realized you could, I would try to fix things and then I’d have to live with the fix, which is almost always worse to live with than the original problem. For me, if the attitude is right and the playing is up to par, you just keep the take. It’s not going to bother you in a couple of days and if it does, you’ll get used to it. Sometimes it turns out that the thing that makes the tune is the grit. These new digital editing tools let you get rid of it, but if you do, I find you don’t have a take anymore. I don’t know why that is, but I think you really have to keep some of the crap intact.

Tell me about some of the tunings you use on the new record.

I used a G-minor tuning on “From Spink to Correctionville.” “Living in the Country” and “Rings” use a dropped-D tuning. On “Twice,” everything is standard tuning except for bringing the A down to a G and the E down to a C. I heard a story about how some slack key players would drape a hanky over their left hand while they play so you couldn’t figure out their secret tunings, and I feel the same way about that one. Chet Atkins gave it to me. He was shown it by Ledward Kaapana. It’s the most beautiful tuning on earth and I guess I should really pass it on to other guitar players. It’s also very practical because only two strings are detuned.

What is your overall philosophy when it comes to open tunings?

Stay away from them! They’re just a waste of time! [laughs] You’ll find you get something you like in a kind of boneheaded way and you end up with tunings that apply to only one tune and you’ll have to tune to get there. If you just play for yourself it might be fun, but if you’re going to actually perform, you’re better off in standard tuning. It’s all available in standard tuning. You only have to listen to the greats like Joe Pass and John McLaughlin to know that. One of the reasons I still use open tunings is because I have to play some of my hits. Since they were written in open tunings, I try to come up with new stuff in the same tunings so I don’t have to always retune onstage.

How have you evolved as a guitarist over the course of your career?

In the beginning, I thought it was all about playing hard, ripping it up and breaking strings, but what breaks is you. You can get so much more power and authority through exercising restraint. As I evolved, I became more interested in the music. Instead of having the power coming from my hands, it now comes through my feet and into the rest of my body. Also, I’ve learned to listen to other people much better. That’s something I get to exercise a lot with Mike. If you listen dispassionately and without study when someone is playing or to a recording, it will do you a lot of good as a player. Chet Atkins, Albert Lee, Larry Carlton, and I were onstage together once and someone from the crowd asked what I learned from those guys. I said, “I can’t learn anything because it goes by too fast, but what I can do is cop their attitude.” Chet jumped up and said “That’s it! It’s about getting something you can wear. The more you listen, the more you can wear that attitude and your playing will benefit.” It’s a really extraordinary thing. And because I listen so much more deeply now, it’s harder but more satisfying for me to write new music.

Why is it harder?

I feel like I’m really missing the boat if I don’t go the final inch to get to something beyond my comfort zone. I used to stop with what I got for free. Now, I look for what wants to come in and that means it takes longer to write the pieces. For instance, a piece called “Gewerbegebiet” from my last solo album Try and Stop Me is still developing. I wrote it in front of crowds because there were problems with it I couldn’t solve myself. If you’re willing to humiliate yourself in front of an audience, you’ll find the piece exerts its own influence about where it wants to go. I love that.

Mike Gordon on working with Leo Kottke

Photo: RCA Victor

Photo: RCA Victor

What made you pursue Kottke for a collaboration?

I’ve been following Leo for a long time. I love his playing. I was driving around one day and one of his songs came on the radio. I suddenly just had this feeling that adding my bass to his sound would work. I wasn’t thinking about joining him onstage, because that would mean I wouldn’t be able to see him solo when he comes into town. However, he’s used a lot of musicians on his albums, so I thought maybe we could record together. I followed through with my scheme by adding an intricate bass part to one of his songs and gave it to him along with my book Mike’s Corner, an issue of Bass Player with me on the cover, and a copy of Story of the Ghost, the most recent Phish album at the time. The package seemed to get his attention.

How do you and Kottke complement each other?

Leo doesn’t need me, because he has bass lines built into his parts. I like the fact that I’m there because I’m wanted and not needed. When we play, it makes sense for him to do what he normally does and have me dancing in and out of it. But as with any great chemistry, an interplay happens that you surrender to like a Ouija board. We don’t have to think when we play together. It’s a great situation for me because I can move around the bass neck intuitively. We use no amplifiers or monitors onstage and stand eight inches apart. So I get my favorite acoustic guitar player in my right ear every night and swim in the sound.

You’re known as an electric bassist, but you play acoustic-guitar bass when touring with Kottke. Tell me about your setup.

While touring this year, I initially used a couple of Washburns and I think the instruments sound great, but I didn’t know some things. I figured out that you have to turn the brilliance knob all the way off and the treble to half on any acoustic-guitar bass if it’s going to sound good. That especially holds true because I use a pick. The sound of the pick with piezo pickups is so clicky. I remember listening to tapes from the tour thinking “The acoustic-guitar bass is a nonsense instrument and everyone knows it. No one respects them. Upright bass sounds big because it is big and solidbody electric bass sounds big because you have the bass amp. Acoustic-guitar basses don’t get the vibration or the depth.” We auditioned 12 other instruments to see if one would work better. The one that won out was the Martin ALternative X. It’s brushed aluminum on the front, so it looks really wild under the lights, and the back is Formica. The neck is made of out of Stratabond, which is a kind of plywood. It’s a little smaller than the other basses we checked out, but it’s really lively sounding and has a nice evenness to it. The sound jumps out of the instrument, which you wouldn’t expect from the size of it. As soon as Leo heard it, he said, “That’s the one.”

What has working with Kottke taught you?

For me, music is about the mind, body, soul, and heart. Leo gets to me in all of those places. After five years of playing with him, I’m always still blown away. He’s always fiddling with his guitar. It’s constant and he comes up with so many new things all the time. His relationship with his instrument is so inspiring. He loves it so much and every note he plays is unique sounding. He’s inspired me to approach my relationship to the bass in the same way.