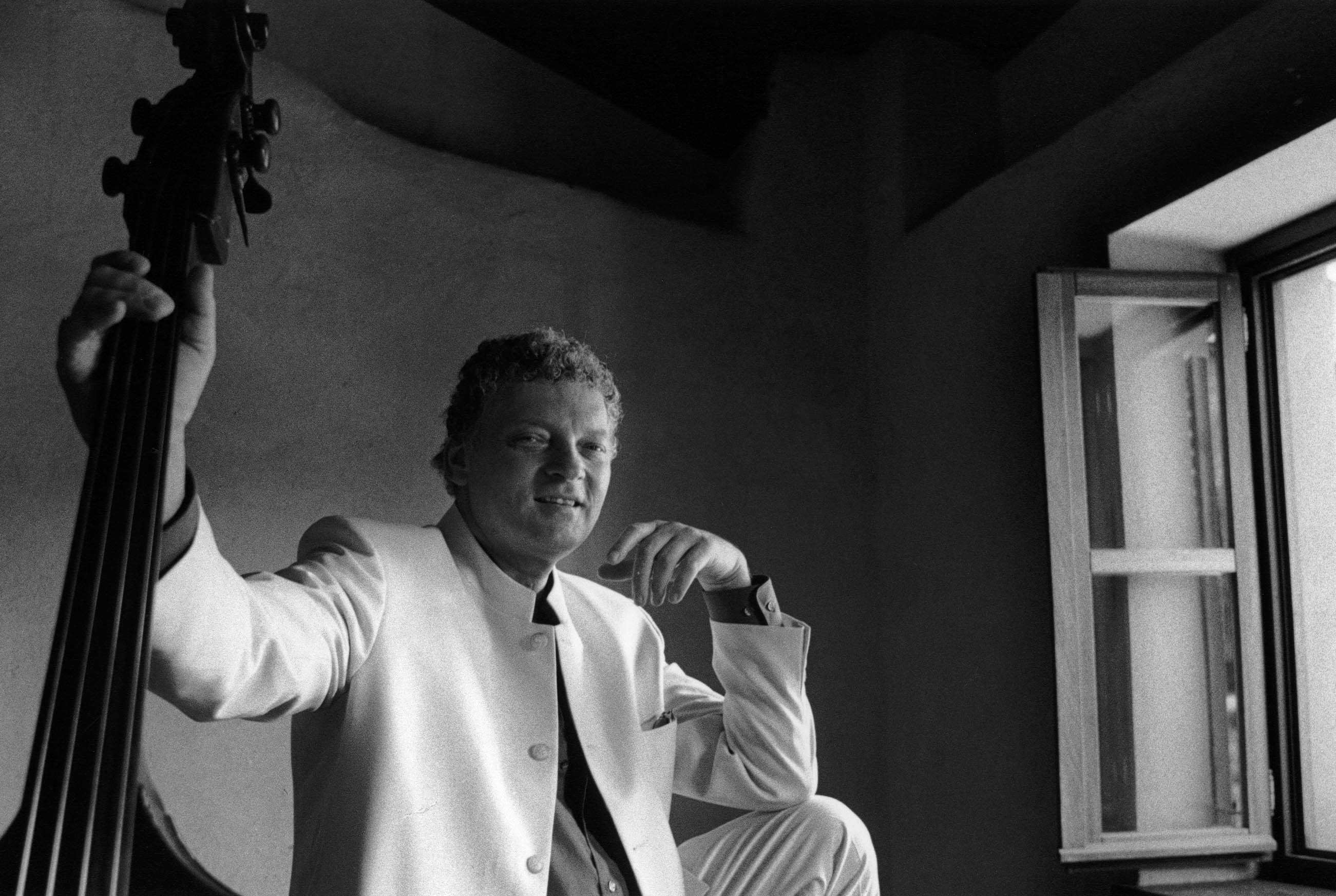

Miroslav Vitous

Freeing the Muse

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2004 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Roberto Masotti

Photo: Roberto Masotti

Freedom reigns supreme on Universal Syncopations, bassist Miroslav Vitous’ 2004 release. For his first disc in seven years, he assembled a dream team of pianist Chick Corea, drummer Jack DeJohnette, saxophonist Jan Garbarek, and guitarist John McLaughlin and gave them one overarching directive: play what feels right. Instead of issuing specific guidelines, he provided the musicians with maps that infused the sessions with an open and expansive mindset. The maps contained the tunes’ harmonies, melodies, and motifs. The rest was left open to interpretation.

The approach is reminiscent of one he took on his first solo album Infinite Search, released in 1969, that also featured McLaughlin and DeJohnette, as well as Herbie Hancock and Joe Henderson. During those sessions, Vitous broke from the traditional role of the bass and used the instrument as a primary vehicle for driving the tunes forward. He also encouraged the other players to reconsider current musical conventions in favor of uncharted, improvisational territory.

Exploring new terrain has been a hallmark of Vitous’ long career. That’s no surprise given that he emerged on the scene during the mid-to-late ‘60s playing with jazz giants including Art Farmer, Stan Getz, Herbie Mann, and Clark Terry. In 1970, he co-founded Weather Report with Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter. Vitous went on to record five albums with the pioneering fusion act prior to departing in 1975. He then relaunched his solo career which has yielded a dozen diverse releases to date, ranging from jazz-funk to solo bass to intimate acoustic duos and trios. Vitous is also on the leading edge of music technology as evidenced by his successful forays into the audio sampling world.

Why did you take a seven year break between solo albums?

I needed to make some sounds. I created and released a Miroslav Vitous orchestra samples library which took an extremely long time to do. It was a four-year project and then it took another three years to redo it in different formats for different samplers. I needed to have high-quality sounds to proceed with my compositions. I love the idea of computer technology, but there were no good sounds. They were all Mickey Mouse sounds. I waited and waited and no-one came up with anything, so I started to work on it myself. It was consuming, both timewise and financially, so I decided to release it to the public to make my money back. It’s extremely expensive to sample a whole symphony orchestra including every solo player.

At the same time, I needed a break from playing because I had played and toured all my life. I was able to get rid of some of my old playing habits. The only way to get rid of old habits is to have a reasonable amount of time off from playing. Your hands will forget to go the way they’re used to and you can teach them how to go new ways. It’s a very complex thing to change after years of playing. I also learned about choosing sounds and putting different sounds together. It was an incredible education. Without all of this, I could not have done the new album.

What made you pursue the orchestral samples project so passionately?

The desire to compose without having to pay $80,000 for a symphony orchestra. [laughs] And also to have it available 24 hours a day to me, whenever the ideas are floating. I’m the kind of composer who composes with sound, not with pencil. There are many people who are the same way. Basically, everyone in the Hollywood community of composers has the library. People all over the world use it too.

The new album was recorded over two years. Describe the process for me.

It was a lengthy process. It was very similar to recording classical music across different sessions where bar 69 to bar 110 are recorded many times until they’re right. You do all kinds of things to make it come out the way you want it to sound. I edited just as Miles Davis did with whatever limited technology he had. It wasn’t made with everybody playing together at the same time. The bass and drums were playing live, on the spot at the same time with no changes whatsoever. After that, I started editing the thing, writing different parts, motifs and melodies for Chick Corea. Then I did the same for the brass, John McLaughlin and Jan Garbarek. Then I took 14 months to choose the right takes for each track and put them where I needed them to ensure it makes complete sense. The album doesn’t sound like it was made this way because there was amazing intuition from all the musicians. For example, in some places, Jack DeJohnette would answer what Jan Garbarek played two years later. It was an amazing spiritual undertaking. I would think “How is this possible? How did he know he was going to play like that?”

Tell me about the choice of players on the album.

Jack DeJohnette was my all time favorite drummer for the last 20 years. There was no question it would be anybody but him. I wanted John McLaughlin because of his presence on my first album and the sound he had with Miles Davis and during the new music that was created in the early ‘70s. I think this album is a next step and I wanted to have that sound connecting the evolution. Chick Corea and I have had a long rapport. I’ve done many things on his projects for a long time, so I thought I’d have him do a project for me. Jan Garbarek is my favorite sax player. We also have an incredible musical rapport and you can hear it. He understands my Slavic melodies and what I use for atmosphere because he’s European and his father was Polish, which is very close to me. I’m from Czechoslovakia. Our musical communication is astonishing because we know what each other is going to play before we do it.

Photo: Roberto Masotti

Photo: Roberto Masotti

Did you conceive the music for the album specifically with these players in mind?

Yes, but I like to break the bar as much as possible so I don’t get locked into the box of the bar. When I made the album, there were no bar lines. They were dismissed. It’s just breath, feeling and motif statements. The music just lives on its own, instead of being limited. I made maps for myself before I recorded with DeJohnette. I followed the maps and they formed the tune as we were playing it. On these maps, I write down the notes, the harmony and the melody, but I don’t write down the exact numbers of bars and how long something is going to last. That’s why it’s more of a map than a definitive reading of music. When you read music, you’re not creating.

You’ve described the music on the new album as a conversation between the musicians.

Yes, on three tunes, “Miro Bop,” “Sun Flower” and “Univoyage,” I put things together in a way that created a new concept. I freed the bass. The bass is not playing all the time on these compositions. It is an equal instrument to the others and we are having conversations. This consequently frees the drummer because he doesn’t have to play a rhythm section role any longer. It also frees the bass player most of all too. The other musicians are also free and can answer each other rather than play traditional roles. I wanted to break that out.

The musicians on this album are on such a level that each has a lot to say and there has to be space for them to say it. So, I wrote the motifs in a way that gives them enough room and lets the overtones ring out before the new statement or melody comes in. I did some of this in 1969 on Infinite Search because of the way I played bass. This is another step forward.

How do you feel Infinite Search redefined the role of the bass?

I didn’t play the bass in a traditional way. I wasn’t playing with the drums’ time going “boom, boom, boom” all the time, with the piano playing harmony and the horn or guitar soloing on top of it. I would come up with motifs and come in with a second voice and tune down the bass. Nobody was used to playing in any other way before that. You have to remember that when jazz started, most of the bass players could not play their instruments well. Most of them were ex-trombone players, so jazz was created with a condition in mind that the bass player is not a good instrumentalist.

Clearly, that changed significantly during the ‘50s and beyond though.

Yes, you had musicians who could play the bass very well, but a lot of them had a hard time. They could play technically, but didn’t know where to put it. They would be overplaying on top of the musicians who were used to hearing “boom, boom, boom” behind their solo. It takes a very good, technical bass player and a great musician to know what to do with this. Scott LaFaro started doing it with Bill Evans. He was the first one who broke this barrier and was having a constant conversation with his instrument.

Why did you name the album Universal Syncopations?

The word “syncopa” refers to a rhythmical note. Syncopations are more rhythmical notes. I feel the music is very universal, so I called it Universal Syncopations. It’s universal because the music is free. When I say “free,” I don’t mean you have to be avant-garde. “Free” doesn’t have to mean going crazy. You can have music that incorporates many elements, not just avant garde things. That is also free. We have to get rid of the term “free” in that way. I am very proud that I was able to capture the creative force in the sound and the motifs throughout the album. There was an excellent marriage achieved between jazz, creative music and classical on it.

How do you look back at 1970’s Purple?

I made that album after Infinite Search. I was working with David Baker, the engineer, and was experimenting with different musicians and material. I had Billy Cobham, John McLaughlin and Joe Zawinul there. They experimented with me. After six months, I thought I had enough material and put together an album. I think there is some excellent music on it. Purple was made before Weather Report started, but you can already hear some material that we later played with the band. There’s a song called “Water Lily,” which has an identical skeleton to a piece we recorded with Weather Report called “Morning Lake.” There’s another Weather Report piece called “Seventh Arrow” that was also on Purple. There was a development of the material on Purple that ended up in Weather Report. It was a stepping stone.

Weather Report, 1972: Eric Gravatt, Dom Um Romao, Miroslav Vitous, Wayne Shorter, and Joe Zawinul | Photo: Columbia Records

Weather Report, 1972: Eric Gravatt, Dom Um Romao, Miroslav Vitous, Wayne Shorter, and Joe Zawinul | Photo: Columbia Records

What are your thoughts about the time you spent with Weather Report?

I enjoyed the beginning of it very much, but it turned into a little bit of a drag in the end because Joe Zawinul wanted to go in another direction. The band was seeking success and fame and they basically changed their music to go a commercial way into a Black funk thing. That’s what happened. I didn’t want to do that, so this is where we had to part. There were some unpleasant things that came with that. I was not treated correctly in terms of the business side. I was an equal partner and basically, I didn’t get anything. We had a corporation together that was completely ignored. If you have a company and three people own it, and then two people say “Okay, we don’t want to work like this anymore. It’s just two of us now,” normally, they break down the stock and pay off the third person, right? Weather Report belonged to all three of us. Sometimes in the music business things like this happen. There was something which was simply not fair about it.

In Europe, I spoke to a writer who reviewed my new album and said “I know two Weather Reports. One with you and one without you. Now, I understand what influence you had on the first Weather Report.” It’s the way the bass was played, which left a lot of room and ground to develop new music. This is what we started to do. I believe my influence at the beginning of Weather Report was much stronger than anyone ever imagined.

You briefly played with Miles Davis. What can you tell me about those days?

I played with him in August 1967 at the Village Gate with a quintet including Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock and Tony Williams. At the time, the group was still playing “My Funny Valentine,” "Stella by Starlight,” and music from ESP and Nefertiti. It was unbelievable. It was the ultimate experience with the highest quality musicians. I played with him for one week, subbing for Ron Carter who was doing a clinic. In his biography, Miles said that week was one of his most creative with the band ever, which of course is very complimentary to me.

I was playing with Clark Terry in a Chicago club called London House. Miles, Herbie, Wayne, and Tony came to the club. They had a concert at the Opera House that night. Miles heard me play and told Clark “Tell the guy to call me next week. I want him to play with me.” That was a fantastic break for me. It was amazing, the same thing happened the next day with Herbie Mann. He also played a concert at the Opera House and came to the club. He walked up to me and said “My bass player is leaving. Would you be interested in joining the group?” Literally, within two days, I had a career breakthrough.

Do you wish you could have worked with Miles further?

Yes. I wanted to play with Miles very much. In fact, Herbie told me later that they were discussing changing bass players a lot at the time because the band had been extremely creative that week. I wasn’t aware of it because I didn’t know how they played without me. So, that was very complimentary to me too. I finally did get to play with Miles once more, just before the beginning of Weather Report in 1970. I finally got the gig again. I was very happy about it, but Miles had changed his music and was going into a period where he needed a bass player to play repetitive motifs and I don’t play that way. Miles wanted the role of the bass to be one, specific thing. I wanted to focus on communication and composition. So, it didn’t work out. I was not the person he needed. I only played one concert. The group had Jack DeJohnette, Keith Jarrett, Airto Moreira, and Gary Bartz. At that point, I said “I’m not going back to Stan Getz or Herbie Mann. It’s time to get something together on my own.” So, I called Wayne Shorter and that’s how Weather Report started.

What’s your take on the state of popular music?

Personally, I think that past 1974, nothing new has been introduced to music. I really feel that way. Nothing of any importance or significant development occurred after the fusion movement that happened with Miles Davis, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Weather Report, and Return to Forever. Fusion took off and then disco came in, which basically destroyed everything, especially business for creative music. I haven’t heard anyone take music a step further. It’s possible that someone has, but I haven’t heard it.

The problem is the money man came in and said “Wait a moment. We need you to play things in a way so people can tap their foot and we can sell one million albums.” That’s been a problem for quite some time now. Disco was a catastrophe for creative music. I have seen some of the greatest musicians in the world fall off the scene because they could not cope with that. The rest of us who were able to survive had to adjust our playing and way of doing things so the businessmen would keep us alive. It’s ridiculous that since disco, money came into the art so strong that we had to stop playing art and start making music to survive and sell albums that have nothing to do with art and culture. I find it very pitiful. Business went so deep into the music that it stopped the growth of music.

In my own career, I couldn’t do this. I refused totally. I would rather make money another way instead of making music I don’t want to play. I was being pressed and pressed and pressed and finally said “You know what? I am not going to just play music for money. Where’s my passion? Where’s my love for this? It’s being killed. Why is this happening? Forget it. I am just going to go to Europe.” It was one of the reasons I left America. The freedom of playing was being cut and cut and cut. Moving back to Europe was the best possible thing I could have done at the time. I had lived in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, and Boston and went back to Europe in 1988. I was able to regenerate my desire and love for music and get back to my European roots. I had been away for 24 years. Now, I have a house in St. Martin and in Northern Italy. I stay in Italy most of the time because I started playing full-time again and perform at a lot of concerts.

I understand you were a top Olympic contender in freestyle swimming during your late teens.

I was on the international team and was going into the Olympic team from Munich when I won a competition in Vienna in 1966 and was able to go to the United States. There wasn’t much choice. I wanted to play music, so I went. Someone gave me something absolutely amazing: the discipline and strength to deal with physical situations. As a professional athlete, you have to conquer so much in training. There are so many difficulties. Even when you cannot go anymore, you have to keep going. You have to catch your second breath. Reaching the height of that condition helped me a lot in my later years when I was in New York. What I learned physically from swimming I transferred to my mental state. You can imagine how tough it was to be a young 19-year-old from a Communist country in New York alone. You need a lot of mental strength to hold things together. I learned how to survive and keep going. I owe all of that to swimming.