Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

BaBa ZuLa

Reinvigorating Roots

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2008 Anil Prasad.

Turkey is a nation in the midst of a dramatic transition. It’s pushing forward with social and economic reforms as it pursues membership in the European Union. During the process, it’s casting an eye to the rear view mirror, pondering and situating the impact of centuries of history stretching back to its pre-Islamic, Shamanic roots on its current hybrid Islamic-secular nation state. It’s a multi-layered country that blends Eastern and Western influences into its cultural mix—a fact that’s particularly apt given its geographic location straddling Europe and Central Asia.

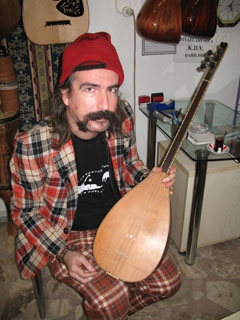

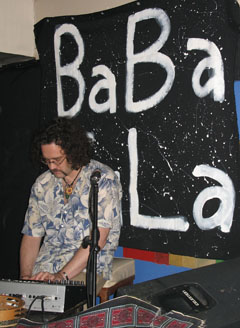

BaBa ZuLa, Turkey’s most beloved alternative music purveyors, provide an ideal soundtrack for this region in flux. The Istanbul-based band combines dub and reggae influences, traditional Turkish instruments, and electronica into a truly one-of-a-kind psychedelic sound. Comprised of electric saz player and vocalist Murat Ertel, electronics and percussion maestro Levent Akman, and darbuka player Coşar Kamçi, the three-piece band creates an enormous sound bathed in myriad melodies and polyrhythms. In concert, BaBa ZuLa is a quartet that also features the talents of Ceren Oykut, a renowned graphic artist that creates and renders projected digital images in real time.

While it is relatively unknown in the West, the saz is the foremost stringed instrument used in Turkey. With three-to-12 strings on a bouzouki-like body, it possesses a distinct, bright, and ringing high-pitched sound that’s pleasing to the ear. It’s at the core of the group’s sound and that of many other contemporary and traditional Turkish acts.

BaBa ZuLa just released Roots, its sixth album. It’s a stripped down affair that represents the essence of the group’s trio interaction. Previous discs featured many special guests, as well as outside producers, but the band was intent on keeping things in the family for its latest outing. The album features 25 mostly short pieces that largely came out of studio improvisations, as well as three dub mixes by noted Japanese producer Naoyuki Uchida.

Listeners abroad may have been previously exposed to BaBa ZuLa in Crossing the Bridge, a remarkable documentary by Fatih Akin now available on DVD worldwide. The film takes viewers through Istanbul's contemporary and avant-garde music scenes with a level of depth and intrigue rarely found in musical travelogues. The documentary has helped elevate BaBa ZuLa’s international profile considerably. Don’t be surprised if they hit your local scene in the near term.

Ertel sat down with Innerviews over Turkish coffee and pastries in an Istanbul café to discuss the new album, the band’s history, and the complexities of life as an artist in Turkey.

Describe the beginnings of BaBa ZuLa.

Initially, I was in a group called ZeN that I formed in the late ‘80s. It was a progressive, psychedelic rock band with some Turkish influences. The band was based on playing our own compositions, but one day, the bass player didn’t show up to a rehearsal. So, we were left in the rehearsal room at the University of Bosphorus with me mostly playing guitar and singing, a drummer, and another guy singing and playing bendir, a round Turkish frame drum. We got bored of playing our own material and started improvising. That transformed the band into one that focused exclusively on collective improvisation. More people joined the band and over the years it ranged between five and nine musicians.

In 1996, a friend of mine named Dervish Zaim from the same university approached me and said he’s completed a film called Tabutta Rovasata which translates into “Somersault in the Coffin.” He had put some music on the film but wanted Zen to create a new score. So, we watched the movie and some guys in the group didn’t like it, while the other three did. So, we picked up a new name just to do the music for the project, and that’s how BaBa ZuLa formed. We just reissued the soundtrack as a remastered CD.

We thought BaBa ZuLa would end with the film soundtrack, but it turned out to be very successful and new possibilities opened up. We were invited to do a live concert, which we hadn’t planned on. We figured out how to do it by performing as a three-piece, along with an American bassist named William MacBeath, who went by the stage names William MacBeth or Bill MacBeat. We went on to perform and jam with him at other concerts, and through him, we also met the saxophonist Ralph Carney, who we also collaborated with. From there, taking in guests became part of the BaBa ZuLa formula.

What does the name mean?

For Native Americans, it means “great big secret,” similar to “Wakan Tanka” in Dakota mythology. In Turkish, Baba refers to “father” or “big thing” and Zula is similar to “secret,” so it also loosely means the same thing.

Compare ZeN’s music to what BaBa ZuLa does.

It was very similar to what we do now, but much more simple and minimal. We didn’t want to stick with formulas, but rather just make music and then try to understand and analyze it later. Also, with BaBa ZuLa, I wanted it to be more focused on Turkish folk influences than ZeN. ZeN was more psychedelic with a little bit of Turkish music, but it also had many Western influences which were becoming too much for me. With BaBa ZuLa, I really found what I was looking for. In this band, we have a term called “defined improvisation” in that a piece may be defined with certain musical terms like a scale or a mood, but we play each song differently every time, yet when you listen to it, you understand that it’s that song. We also didn’t want to do the same thing as ZeN. We wanted a more song-oriented approach that included more traditional forms and the improvisational components that are inherent in most Turkish music.

Why was it critical to incorporate the Turkish folk component into BaBa ZuLa’s sound?

I really thought it was very important to find my roots and go back to the music I listened to during my childhood. There were great artists like Baris Manço and Mogollar who combined elements of Turkish folk with rock and roll who were really influential. When I was a child, I would get their 45s and listen to them over and ever. There’s also a form of music in Turkey called Ashik music, which means “the one that’s in love”—but not only with a woman or man. It also refers to being in love with God and nature. An Ashik is a minstrel who goes from village to village, carrying a saz, and he becomes a guest of the community. People give him a place to stay, and food and drink, and after awhile, he goes to another village. There were a lot of people like that in the past. Several Ashiks came to our house and were really important to my musical development. The main reason I took up the saz was because I was always seeing them.

I should also mention that my father, Mengü Ertel, was a graphic artist who did covers for many records by Turkish artists, which also proved highly influential for me. For instance, there was an artist named Ruhi Su and my father did all his album art direction during his lifetime, which came out to about 15 albums over a 24-year career. Before finishing his records, he would come over to our house and perform the whole album live. My father recorded it onto reel-to-reel tapes and he listened to them in the house while thinking about the cover design.

Tell me about the concept behind the band’s new CD Roots.

We wanted to make music that felt more like what we do in concert. Our previous two albums had lots of guests and production, so we chose to have just a couple of guests on the album and record mostly as a three-piece band, just like we did when we first formed. We also wanted to take advantage of recording techniques from the ‘50s and ‘60s in which they recorded in smaller studios and used acoustic technology. In addition, we wanted to get even further back to the roots of Turkish music on the album by using more indigenous Turkish instrumentation. We’re unhappy with the idea of globalization in which corporations want everyone to think about the same things, eat and drink the same things, and listen to the same music worldwide. Their strategy is to cut people off from their roots. So, we went in the opposite direction and tried to connect more with our roots. The album does have a mix of styles though given that we included a few dub mixes at the end of it by a DJ friend of ours from Japan named Naoyuki Uchida. He has a different sound from Mad Professor who we used on previous albums. Naoyuki takes a more minimalist and Eastern approach.

Describe the creative process behind Roots.

We began with five composed songs and the rest of the pieces were completely improvised. We had a two-day session during which we decided we would play short songs. We recorded 82 improvisations live as a trio and from those, we chose 21, which formed the basis for the rest of the album. In a way, this relates back to ZeN because that group was entirely about improvised music. During the previous BaBa ZuLa albums, we focused more on composed music, but we wanted to get away from that a bit because it started to feel a little formulaic. Having a balance of improvised and composed material feels like a good mix for the future too.

What made you want to incorporate dub influences into BaBa ZuLa’s music?

I’ve always liked the echo effect and delay very much. It’s always been influential, even when presented in a kitsch way. The music of Jamaica has been an influence on me since childhood. Some of the music that was most important to me as a child was Harry Belafonte’s calypso stuff. It gave me a grasp of Jamaican sounds. Then when Bob Marley became famous, he became a very big hero of mine. I liked that he was one of the first non-American, non-Anglo-Saxon musical heroes in the world. I really learned about reggae through him and that’s how I also found out about dub music.

The most interesting music to me is that which is influenced by reggae, including dub and reggae-influenced drum-and-bass acts. Lyrically, I also like the rebellion against the system and government represented in the music. It also stands for freedom, peace, and equality which are all things I really admire. Going back to Marley, he really made the point that it’s a white man’s world and that there is inequality to be overcome, and it’s that way in Turkey as well. Rhythmically, I also find dub very interesting because of the strong downbeats. In blues and rock, the downbeat usually hits on the second and fourth beats, but in Jamaican and Turkish music, they mostly hit on the first and third beats. So, there’s a link between two musical cultures there. You can actually replace a reggae drum machine with a traditional Turkish drum machine and it doesn’t feel strange.

How did you hook up with Mad Professor, who produced the band’s Duble Oryantal and Psyche-Belly Dance Music records?

When we started Psyche-Belly Dance Music, we had a problem with the drum machines we were using. They can be very dangerous in that they can get cheesy pretty fast. You really need to have a great sound to use them well. We were thinking about the problem and Cem Yegul, the executive producer from our label Doublemoon, said “You’ve made a very dubby album. Why not get a very good dub engineer to mix it?” We thought that was a very good idea. We thought about Lee Perry, Scientist, and Mad Professor. We thought Lee Perry would be risky [laughs] and felt that Mad Professor would be our man, so we contacted him. He came to Istanbul to mix three tracks, but we were so happy with what he did that we asked him to continue. He’s a really great musician. He also really deserves his name. Sometimes he fucks up equipment because he really takes things to the limit. [laughs] He’s a guy that’s done lots of things with electronics, but also with a deep roots feeling, which parallels what we’re about. We also have the songs too. We call the combination “Oriental Dub” and we hope to create some more music with him in the future. He really felt like a member of the group. He has a great grasp of what we’re doing and can really work some magic on the control board.

Your main instrument is the saz. Describe it for people who are unfamiliar with it.

It’s the main instrument in Turkish folk music. It’s been named differently throughout history. At first, it was called the kopuz when Turks lived in Asia. According to some art historians, this may have been around 1000 BC until sometime between 650 and 1000 AD when there were Arabian attacks and genocides against Turkish people. The kopuz was made out of a horse skull. Its body was covered in leather and it had a fretless fingerboard. The instrument was played with a bow. During this period, Turkish people, mostly Shamans, were killed and forced to convert to Islam. Lots of instruments resembling the Shamanist roots were banned and burned. As a result, the kopuz became less popular but continued its existence in various forms and names.

When Turks became Muslims, some of them came to Anatolia under the name of Selcuks. In the manuscripts of the Selcuk Turks we can see the word saz used for the first time, so it was renamed during this transitional period. It likely changed a bit during this time and had a wooden body instead of a leather-covered one, with metal strings replacing the gut ones. Also, the bow began being replaced by fingers and plectrums. Around this time, the Turkish people spread Islam themselves, and special ways of interpreting Islam were born around Anatolia. Some of the most beautiful examples for me are the Alevi, Bektashi, and Mevlevi orders. Those three sects of Islam are all closely related with the Anatolian Turkish culture. Their approach is to link Islam with the old Shamanic ways, and also through dance and music. For the Alevis and Bektashis, the saz became a symbol of Anatolia and revolt. This relates to the period around the 14th century, when the Ottoman Empire was founded by the Turkish people and others from Anatolia. At this time, the saz was seen as a symbol of opposition against the ruling Sunni sect. So, the Ottomanic Islamic authorities sought to ban it again. Around the 18th century, the name baglama emerged. The name means “to tie,” which I think must reference an instrument with tied frets, exactly as it is nowadays.

There is a great song by Ashik Dertli from the end of the 18th century which still refers to the instrument as a saz, and describes the situation perfectly:

Telli sazdir bunun adi.

(Stringed saz is its name.)

Ne ayet dinler ne kadi.

(It doesn’t listen to the verses of Qu’ran or the sayings of Muslim judges.)

Bunu calan anlar kendi.

(The one who plays it understands himself.)

Seytan bunun neresinde.

(Which part of it belongs to the devil?)

So, the instrument has three names. I prefer saz, but you still hear it called baglama, which is an even more popular name today. I should also mention that the bouzouki, which is far more well-known throughout the world, is nothing but a saz with a longer mandolin neck with frets and tuners. It was brought to Greece by the Rembetiko players who lived on the Turkish side of the Aegean Sea around the 1920s. It is named after the most popular tuning of the saz called bozuk, which means broken tuning.

When the kopuz evolved into the saz, it had gut strings that were played with fingers or a plectrum called a mizrap. Later, frets and steel strings were put on it and it began being played with plucks. Now, it’s usually set up with three sets of double- or triple-strings, with each grouping tuned in unison. Sometimes each group of strings is a combination of bass and treble strings. The fretting system is different from Western instruments in that it has 17 notes per octave. So, it has the 12 tones of the Western scale, plus five tones. And the additional five tones are not quarter tones divided equally, but another system called Comma, which is a Turkish system that wasn’t written, but passed down orally going back thousands of years. So, the division of the frets, in essence, represents the basis of Turkish melodic theory. In Turkish classical music, they divide things into between 24 and 32 and sometimes even more frets, which to me is impractical. It results in too many little frets. So, in Turkish folk music there are 17 frets. We also have certain scales which are called maqams or ayaks in Turkish folk music. These are different from typical scales in that they don’t always have just one octave, but usually two. And they aren’t always seven-note scales. Sometimes they are eight- or nine-note scales that begin from low notes and go into the high notes or vice-versa. There are also other scales that travel around, resulting in three main types of maqams.

The saz types are a bit like saxophones in that they start from soprano and go into the baritone registers. Each instrument covers a different range of notes and sounds. The big one is very large. It’s called a Meydan saz, which means “the big place where you held your meeting.” Therefore, it has a neck so big that you can’t hold it—you have to put your arm around it to play it. It offers very powerful volume and sometimes has nine strings arranged as three sets of three. The baglama stands at the middle of the saz range with a longer neck than a guitar. The smallest saz is called the three-stringed saz and only has three single strings on it.

You play an electric version of the instrument. Tell me how that variation evolved.

The electric saz was born in the ‘60s because of an electric guitarist named Erkin Koray. He’s not a saz player, but he came up with the electric saz idea. He wanted a specific sound and had one made for him. It’s a similar story to the blues guys who came to Chicago and other big cities with noisy clubs and couldn’t get their acoustic instruments heard, which is why they went to electric guitar. It’s the same story here. The electric saz is like a city version of a saz. It’s much easier to play at a high volume. One of the problems with it is that I get uncontrolled feedback from some electric sazs because they have hollow bodies. That’s why I decided to make a solid body electric saz. I’ve also added MIDI capabilities to one of my sazs, which I’ve been experimenting with in the studio.

I find the electric saz very interesting because it is the first and still the only Turkish instrument that has been electrified and modernized. It also is the only instrument that has links starting from the pre-Islamic roots of Turkish culture and then Anatolian culture and now modern day Istanbul.

While visiting Istanbul, I noticed there were few books or films documenting the Turkish music scene beyond Crossing the Bridge.

There are few documents, which is a problem. There are really fantastic musicians here, including a lot of old ones who could die any time. There should be books and films made because they know lots of things that young musicians don’t. There are also lots of old recordings that have yet to be re-released so people can have access to this important cultural information. Unfortunately, I think people are thinking very commercially here. Only the idealistic ones are looking beyond that realm. Things are changing little by little. One good example is old Turkish film songs from the ‘70s are resurfacing. Before the military coup in 1980, Turkey had the third biggest movie industry after Hollywood and Bollywood. Many of these films have been recycled on television and have worked their way into everyone’s subconscious. So, they took popular songs from those films, compiled them on a CD called Belkis Ozener and it became a number one hit. Since this record, people realized that old music can sell and they’ve started to pursue reissues, but the artists aren’t always treated with respect. For instance, for Bariş Manço, a funk-rock pioneer, there is no complete album of his released in original form from his ‘60s or ‘70s output. The songs are scattered across compilations. The albums should be reissued properly, in their entirety. Having said that, it’s good that there is a new respect for older Turkish music.

How do you look back at Crossing the Bridge?

It was a real milestone because there was almost nothing available on the recent music scene in Istanbul and Turkey. It’s a very influential scene and people should be aware of it. The movie was done by a Turkish guy named Fatih Akin, but he was born in Germany. So, a lot of Turkish guys got pissed off and jealous because they didn’t think about doing it first. In particular, lots of Turkish directors were upset because the film was so successful. Many say “It doesn’t represent the whole scene. This is not all of Istanbul.” Of course not. It can’t be. People should use the film as a motivation to create their own movies and focus on their favorite artists. A lot of things have changed since the movie. There are a lot of great things happening for Turkish musicians and we can feel it. We’ve been able to tour Europe and Japan, and these things could not have happened this fast without the film. We’ve also been on CNN, Euronews, and other television networks as a result

BaBa ZuLa is one of the main acts featured in the film. How did the band get involved with it?

I knew Fatih, but I first read that he was planning to work with us in a magazine. [laughs] I was really glad because he’s a director that I really admire. The collaboration began at a club called Peyote in Istanbul. They asked BaBa ZuLa to be the artistic directors for the venue, and the first thing we did was ban all the guys who played nothing but covers. [laughs] Most of the bands and musicians we chose to play at the club like Replikas and Selim Sesler made it into the film. When Fatih talked to them, he learned about their influences and sought them out for profiles too. It was a very natural and sincere project. The film also put me in touch with Alex Hacke of Einstürzende Neubauten, one of my favorite bands. Through him, I also met people like Lydia Lunch that I really love. The film proved very important and has influenced a lot of musicians. A lot of artists now come through Istanbul who are excited about the scene and want to be part of it.

BaBa ZuLa’s live show is highly acclaimed. Describe what you’re going for when you perform.

We really enjoy playing live because like Jean Baudrillard said, “We are living in an age of simulation.” And those simulations are getting better and better to the point where the difference between simulations and reality are becoming less and less. In this age, we feel a live concert should really be something. It should be better than a DVD in your living room. You should go to a concert knowing it will be the only possible time you can experience that unique event. To that end, we have improvisational elements in the concert. We also have multidisciplinary levels of art, including Ceren Oykut, who is drawing artwork that is projected on a screen throughout the show. She is a very important element of the experience. She helps draw people into the music. She also helps tell the stories of the songs to people who see us when we perform abroad. Most of the time, people don’t understand Turkish and she helps bridge that gap. We also have the element of belly dancing, which is a very interesting style to incorporate onstage. We don’t use belly dancing in a tourist sort of way. We are thinking about it at another level in that everyone has a connection to their mother’s belly. It is where we all come from. It’s true that belly dancing movements are erotic, but they are also linked to the act of giving birth. Belly dancing also links us to the Shamanic, pre-Islamic roots of Turkey that some people are trying to get the Turkish people to forget.

Is there a political component to BaBa ZuLa’s music?

Yes, the Ashiks were very political, and as my role models, infused me with including that idea in my music. When I hear there is injustice around me, I really get angry and want to express my thoughts about it through music. I want to fight lots of evil stuff that I don’t want in this world. The lyrics aren’t always directly about politics, but rather the politics of life. We have lots of songs about animals, plants, and nature. Some people criticize that and say “Why don’t you deal with important matters?” For instance, we have a song called “Leek” which I think has an important message. We survive by killing animals and plants, yet we don’t have any respect for them. No-one can tell me that a human being is superior to a plant. We don’t know that. It’s a life form and maybe a better life form than a human being because it comes from the Earth and has a real relationship with air, water, and the sun. And when it’s dead, it becomes part of the planet. It has senses and a way of life and we should respect it. The same goes for animals.

Some people think animals are dumb and stupid, but this might not be the situation. In fact, we might be the dumb ones. The bears might be more creative than us. You can’t judge these things by the weight of your brain. I’ve always thought about these other angles. When I was a kid, I always saw Westerns that portrayed the Native Americans as the enemy and later found out that they were actually the good guys, not the bad guys. BaBa ZuLa’s lyrics reflect those perspectives and sometimes people don’t like them. There are people that even want to ban us because of this. Five songs from our Duble Oryantal were banned from Turkish state radio because of their lyrics. “Leek,” “Children of Istanbul,” I Think I’m Pregnant,” “Free Spirit,” and ”Oh No, My Uncle Came” were all banned. The lyrics are nothing compared to what you hear in America. Take “I Think I’m Pregnant” for example. It’s about a girl that tells a guy she’s pregnant and that because of this, they will be banished. Later, the listener finds out the garden she’s referring to is Eden, and that these two are Adam and Eve. That was enough to have the track banned.

How did you react to being banned?

I can’t understand it. There are lots of weird examples of censorship with the Islamist government. There’s even a growing feeling that if you write lyrics that are considered controversial you could be murdered. There have been artists that have had to move away from Turkey because of political or religious persecution related to their art. You might have a case where lots of people support what you do, but there could be 10 maniacs out there threatening you that make the situation unlivable. Music has always been a problem throughout Turkish history. People were killed because of their songs and music going back centuries. Even as recently as 1992, more than 50 saz players, poets, and writers were staying at a hotel in Istanbul that a fanatic Islamist group set fire to. Thirty of them were badly burned, suffocated and lost their lives. Even my own family has had problems because of the military coups in Turkey. Some of them were put into prison and tortured.

Today’s conditions aren’t as bad as the past, but we don’t know what’s going to happen in the future. There’s a feeling that anything could still happen and things may get worse. Maybe I’m overly paranoid, but the current Turkish government is acting in unison with the petrol-oriented powers, including George Bush and the Saudi Arabians and I really don’t like it. Our government tries to seem liberal and acts like our people are free, but the truth is, only if you are rich can you act like you are free. If you’re a poor person, you live in terrible conditions and face a lot of economic and societal pressure. There is heavy stuff going on here, including a war in Iraq, so things are very difficult.

An example of how the government pretends to be liberal, yet really isn’t, manifests itself in the fact that you can’t go on television and sing about certain things. I really envy Western musicians who can talk about God, religious matters, and the government in the media. They can freely express themselves and you cannot really do it here. The worst part is the self-censorship that has taken hold in Turkey. Because you know you cannot talk about certain things, you censor yourself before even making an attempt.

Does self-censorship affect BaBa ZuLa’s output?

Yes. It’s sad, but true. I use art as a filter for my thoughts and to try and talk about certain things at certain acceptable levels. If I didn’t take this approach, it would be very dangerous for me. Look at Orhan Pamuk, the Nobel-winning Turkish author. He is living in New York City now, partly because he was threatened for his views. A fantastic classical pianist named Fazil Say also dared to comment on the problems in Turkey and how the government is trying to move in a fundamentalist Islamist direction by modifying secular rights in favor of Islamic laws. There were lots of insults and attacks on him, and he’s just a classical instrumentalist.

There is also Hrant Dink, a prominent Turkish-Armenian writer who was shot dead outside of his newspaper’s office in Istanbul. He was a peaceful man who defended the rights of Armenians who live in Turkey and Turkish people abroad. So, we as artists try to do our best and protest in the way we can without overly attracting the attention of the fundamentalists. However, most of our songs with lyrics remain banned from radio and television. Most musicians that appear in the media don’t talk about anything other than love and relationships. Young people are really being brainwashed by television and radio because they aren’t being told about the important problems around them.

BaBa ZuLa is the most popular alternative music act in Turkey. It’s surprising that you can be that well known, yet not have your music played very frequently.

Word of mouth is a big factor in our success, which is a great, organic way of building a fan base. The Internet has also played a really big role in attracting attention. I should also mention that it is possible to talk about serious matters in your art here, but you get a small audience. This is largely because media outlets are owned by fewer and fewer people. There is an underground movement in comic books and magazines which tell the truth about what is happening and I have hope and faith that these will turn some young people onto some new ideas.

What’s coming up for BaBa ZuLa?

We’re just starting to think about the next album now. We did some recording with Lydia Lunch, including two songs and one improvisation. We are also planning on recording with Jaki Liebezeit from Can. We’ve played with him a few times over the years and really like him. Jaki is a great drummer and can play the Turkish odd time meters and rhythms. He really has a great grasp of Turkish culture. I also recently performed with the Patti Smith Group in Istanbul which was quite an experience. I played on a couple of songs, including a cover of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” I’m hoping we can do something with her in the future too. So, there are a lot of possibilities for the upcoming BaBa ZuLa album and I’m really excited about how things are unfolding for it.