Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

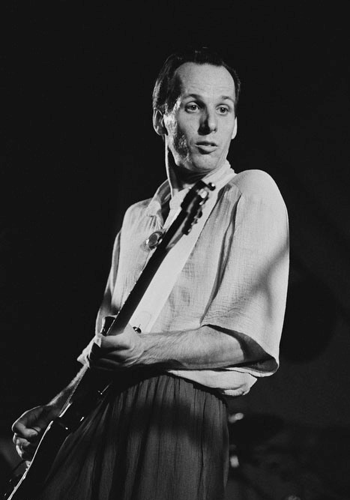

Adrian Belew

The Mind's Turntable

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1992 Anil Prasad.

Adrian Belew is many things to many people. For Frank Zappa, Talking Heads, David Bowie and Paul Simon, he's an eclectic virtuoso guitarist. For King Crimson, he's a charismatic and dynamic frontperson. And to his ever-growing fan base, he’s a singer-songwriter of the highest order.

Belew's last two solo records Inner Revolution and Young Lions combine the best of those worlds. They’re wide-ranging albums full of straightforward pop nuggets, muscular instrumental workouts and more experimental pieces. This interview explores the making of those records, his recent work with Bowie and the potential for a King Crimson reunion.

Inner Revolution has a much rawer feel than your last few albums.

Yeah, I tried to do that. About halfway through the record, I decided to put some more aggressive songs on. The first few were songs like "I'd Rather Be Right Here," "I Walk Alone" and "Everything." Then I decided that to really balance things out, you're gonna need a few aggressive things. Plus, I've been dealing with this recording style of using less information per song. In other words, having three instruments doing the job of six. That accounts for some of the rawness too. I think these are more pop songs than ever to me, but I just wanted to keep it simpler, more direct. Also, I knew that this would be music I was going to play live. I kept in my mind a vision of a band playing it.

Young Lions was a pretty direct album too.

Well, I had very little time to make that album—only 10 weeks. That's a remarkably short time to write and record 10 songs—especially if you're doing everything yourself. The elements were kept simple because I didn't have the time to stop and do the lengthy process of experimentation and sampling.

Was there a particular inner revolution that inspired the song of the same name?

It really came from conversations I had with my girlfriend Martha Thompson. She studies communication and nearly has a masters degree. The idea of an inner revolution is a theory of hers about how things can change dynamically in your life. It could be something that causes you to change or it could be you causing yourself to change. So, the general message that I read into the song was as it says: "If there's something in your life, you have the power to change it." And my life has gone through some dynamic changes lately.

What are some of the dynamic changes?

In the past two years, I would say going on tour with David Bowie for nine months was a big change in my life. On a career level, that was one of the biggest steps I had taken in a long time—not only because of the link there was, but also the finances of it and the whole scope of everything. That changed a lot of things. Also, in the last two years, I decided to get divorced and start my life over. I really felt my marriage had reached a complete failure state where I could no longer be myself and actually be the person I needed to be to do what I want to do in my life. This took a long time to work through and decide—a big decision. Following that, I met Martha and fell in love and that was a giant change in my life. So to me, a lot of this record revolves around the hope of a new love, of a new start in your life and a more positive feeling. Basically, I feel better than I've ever felt in my life, so I wanted to write some songs about that.

"I'd Rather Be Right Here" is about a fear of flying. I was surprised to learn it's autobiographical.

It's the strangest thing. It's totally illogical and it just came on me a few years ago. This has happened to a number of people I know—David Byrne and David Bowie. I used to love flying. In fact, I even have flown planes! I took flying lessons for a little while. I was always thrilled by airports and the whole idea thrilled me and then I don't know what happened. This real illogical fear started and now with the plane, there are times when I get up to move to another seat because I think I'm gonna help the plane a little bit! [laughs] It's that bizarre and stupid. It gives a great deal of humor to my friends. Whenever we start the take-off, my hands break out in an amazing sweat. Sweat just pours off of my hands. The guys in King Crimson used to laugh at it. They'd always say "Watch this—watch his hands!" [laughs] It's some sort of stigma. It certainly is weird. I wish I could get rid of it.

On "I Walk Alone," you have a Roy Orbison thing happening.

Yeah, that was the one song I wrote when I was on the Bowie tour. I used to lay in my bunk in the bus sometimes when I would get tired and try to think up songs. That was one I thought up and only later did I work out the chords and what it should be on the piano. Then I realized as I was doing it that it had that emotional timbre of Roy Orbison. Given that Roy was an influence on me when I was a kid, I thought it would be kind of nice to do something in that vein. Not many people write those kinds of songs these days. The only thing I left out was the big ‘Roy note’ that he always hit at the end of a song. [laughs] But I didn't want to copy him to that degree. I just wanted it to have that that overall quality of his voice.

You have a cover of the Traveling Wilbury's "Not Alone Anymore" on your last record.

It was around Christmas of 1988 when that song first came out. I was in the middle of doing Mr. Music Head. When I first heard it, I couldn't get rid of it and it haunted me. After three days of singing it non-stop, I decided to record it just to get it out of my mind so I could press on and finish Mr. Music Head. I decided not to put it on that record because it was too close to Roy Orbison's death and it really didn't fit that album anyway.

Tell me about "Only A Dream."

It began as a drum track while we were testing mike technique and sounds for the drums. I went ahead and played the drum track and really liked it because it had a lot of different drum rolls and things. I wrote the song over the top of that and it came very quickly. As soon as I worked out the chords, I knew what the melody would be. I always let the songs tell me what they want to be about and it seemed to me that this was a big dynamic-sounding song and therefore could be about something larger than some of the other subject matter. So, I went back to my usual "what are we doing to the earth?" plea. [laughs] I always like to include something like that on a record just to remind people who may not know of my convictions that I believe we are making some big mistakes in the way we are treating our planet.

Are you an active environmentalist?

No. I think my action is simply that what I can do is write songs about it to bring about some awareness and that's as far as I go with it. I don't really participate in any fundraising or anything like that. I think it's a private matter anyway. I think it's one person at a time doing what they feel would help. Even if it's just recycling, it does help.

Rumor has it you're back in a reformed King Crimson.

No, not really. Not officially.

Robert Fripp has been openly discussing it.

Well, we've only been talking about it at this point. I'm not certain it's going to happen. It looks positive that it could happen. I think until we sit and play music together, I wouldn't really be able to say for sure, but I'm excited about the possibility. I met with Robert last summer and we've talked a few times on the phone and it all sounds pretty good. I'm just not sure. It would have to be done in a newer way and that's what we're working out. If it was vital, new, unique music, then that would really interest me. I still really love that band. It's funny. When you play in a band like that and the years go by, all you're left with are the good memories—even though the band had a lot of truly awful moments for me. The end result is that the band made some very adventurous music and that's all that matters.

I understand Jerry Marotta is replacing Bill Bruford in the proposed new line-up.

Yeah. I don't think Robert wants to have Bill involved. There was a lot of conflict built into that situation. I think Bill is also entrenched in his new projects. Personally, I love Bill. He's a remarkable drummer. I learned a lot working with him.

Do you think tension was a catalyst for some of the better music that came out of the group?

I'm not sure if the music is a product of that or not. I'm not sure if you could still make the same music. I'd like to believe you could without all that tension. It's just the potential of all four musicians put together. Whether there were pressures beneath it or not, I think it would have still made the same music.

What is the biggest challenge for King Crimson to operate in the ‘90s?

Well, probably to overcome the stigma of being nostalgic—of reuniting. If we could have Crimson be the band of the 1990s, that would be terrific wouldn't it? [laughs] I must admit, I had a much better time with Robert this time personally, but Robert and I always got along real well. I still think we've both changed, grown up and matured some. Who knows? Maybe that accounts for a lot the differences. You have to approach Robert with kid gloves a little bit, because he's an unusually opinionated person. You have to learn how to, umm, like that. [laughs] He can be a hard guy to get along with, but he's always treated me very well. We really have a good friendship and a good musical understanding. I'm just concerned whether King Crimson is the right thing to do with my time in the '90s, because I'm really enjoying being a solo artist quite honestly. That gives me a lot of autonomy and I'm a little scared of giving some of that away.

Why were you asked to replace Gordon Haskell’s vocal on "Cadence And Cascade" for the King Crimson boxed set?

I was going to visit Robert over the summer for a couple of days and he suggested that "since you're here, why don't you do something on this new compilation?" So, it was entirely his idea, but I enjoyed singing it. I always liked that track even though I had no involvement in the original version.

Why did you choose to cover King Crimson's "Heartbeat" on Young Lions?

"Heartbeat" was the only song I can think of that I brought into the band complete as one of my own songs. Most of the time King Crimson wrote together. I felt the band took the song over and made it differently than I would have done. I always thought it would be nice to do it the way I had it on my mind's turntable.

That song had the makings of a hit single when released, but didn’t quite get there.

We used to laugh at things like that. We called it the "Crimson Curse." Everything we did, even if it was a pop song, wouldn't see the light of day on radio because the band had such a reputation for being outside.

Do you miss recording within a band format?

No, I don't actually. I prefer recording alone. I approach recording more like a painter approaches painting. It's the challenge of working through all the problem solving, of how to get to the music that you hear in your head that I find most attractive about creating music in the first place. Quite simply, it’s more challenging to do it all yourself like a painter. I have my own vision of how to do it. And if I can do it, I'm gonna try to do as much of it as I can on my own. Also, I think that in bands I've been in during the past, you get tired of having to compromise so often.

Did you tinker with some of the old tracks that appeared on the Desire of the Rhino King compilation?

There's a different version of "Lone Rhino" and there's a new song that was never on a record before that was on a Guitar Player flexidisc. Other than that, they're the same mixes. We remastered everything and they probably sound a little better.

I could swear you changed the bassline on "Big Electric Cat."

That's very observant. [laughs] There was a mistake in the mastering at the front of "Big Electric Cat" that cuts off the first note and seems to turn the beat around.

What can you tell me about the Prophet Omega who does the spoken word lyrics on "I am what I am?"

The Prophet Omega grabbed hold of my brain and I wasn't able to get rid of him. He is—or was—a radio evangelist who worked out of his apartment in Nashville. I got ahold of some tapes of his radio show, but haven't been able to locate him or determine the age of the tapes. I think they're about 15-20 years old. I felt his voice was so contagious and charismatic that I thought he should live on in one of my songs. So, I spent a day in the studio dropping my favorite lines carefully in the right place in the music so they would make sense and work rhythmically. I've listed him as a co-author, so in case a couple of hefty guys drop by my place someday, I can say "here's your money." [laughs]

You've worked with Bowie before, but how did the collaborations on Young Lions come about?

It was really simple. He called me while I was on tour for Mr. Music Head and we spoke about the idea of doing the Sound and Vision tour and also doing some new music together. He also offered the idea of using my touring band—Rick Fox and Mike Hodges. We've always been good friends and so far, it's been the best tour I've ever done.

Are you planning on doing another instrumental album in the future?

Yeah, I would like to do that, I don't know if I'll get that freedom from Atlantic or not. I've been letting material like that accumulate and sometime I'll find something to do with it. I'd rather do a movie soundtrack or something. I think that kind of music needs more of a purpose to exist because there's no place in the market for it. Also, I think it would be a dangerous step for me to take at this point on a career level too. I know that Desire Caught By The Tail lost me my record deal with Island. That was no big deal because I went over to Atlantic and did so much better with them. I'm happier, but still, that period was confusing for me.

You’ve done some television ads for a company in Japan called Daiken. What did you make of the experience?

The commercials don't tout a product as such. It's very different. They do a profile about me. In other words, the commercial is about me and at the end it says "I'm always unique, like Daiken is." That's it. I don't have any problems with it from an artistic view. It's not an artistic thing, it's a commercial thing—a thing you do for money and I enjoy it a lot. In the United States, it's frowned upon for an artist to do commercials. It's not looked at as artistic enough. But in Japan, people do commercials there who wouldn't do commercials here because they have a different outlook on it. The commercials are very short and often they're the best things on television. [laughs] People like Robert De Niro and David Bowie have done commercials there who wouldn't do them in the States. I was told that it's one of the only ways for a non-Japanese person to achieve stardom in Japan because they don't play the music on the radio. You can't go through the normal channels. So, the best way to be popular is to do these television commercials. A lot of people do them for that reason. I did them because it was an attractive idea and because the money was good. I really enjoyed it. It was like making a rock video. I liked the end result. I wish they'd show it here. It's a great little profile of me.

How old are you in the cover photo of Young Lions?

That's me at age five. It was taken when I was on my way to Sunday school. I have no idea what the stuffed animal I'm carrying is though. Some people have said that it looks like a duck or a skunk. One of the reasons I put that on the cover was because I first got interested in music at that time. My parents would have me sing with records. You get hooked on the applause.