Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Bill Laswell

Telling Stories

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2017 Anil Prasad.

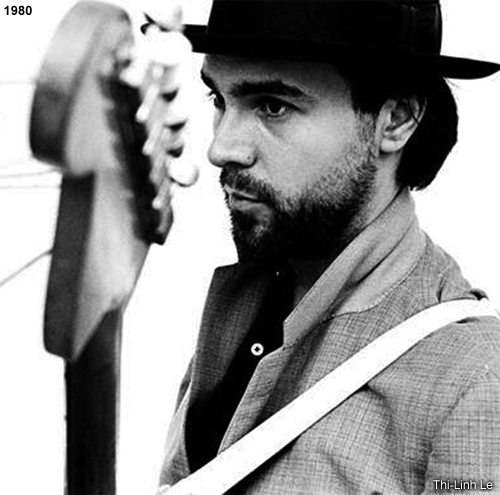

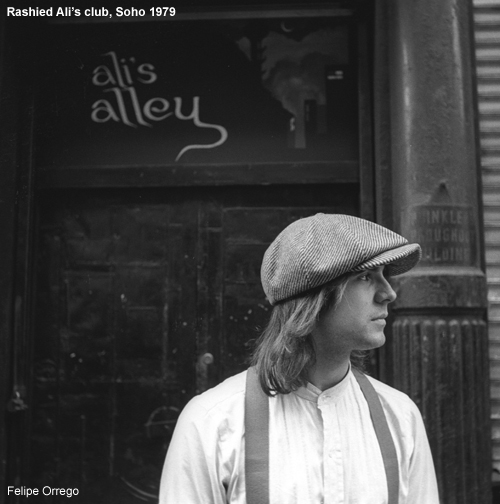

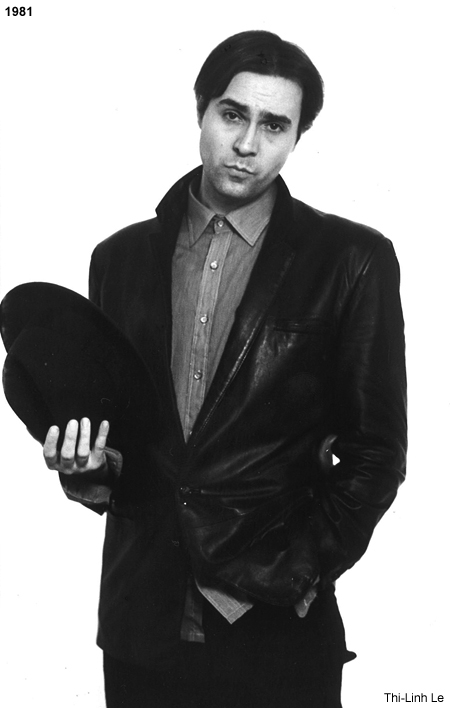

Two critical skills producer, bassist and composer Bill Laswell has emphasized and evolved across his nearly 40-year career are the abilities to adapt and improvise. Whether it’s within the music itself, dealing with mercurial musicians or facing the reality of changing business models, Laswell is a survivor. He continues to give shape to the amorphous across all fronts.

Laswell has helmed hundreds of records and projects, and influenced generations of musicians, producers and listeners. His openness to capturing what happens in the moment, including sometimes accepting mistakes as serendipitous opportunities, is key. His ability to mediate opposing creative and business forces is also critical to his success.

Much of Laswell’s philosophy is derived from a dub mindset. Negative space, drone, ambience, and dark rhythms are prime drivers in a great proportion of output under his own name, as well as shifting lineups that have recorded as Material, Praxis and Sacred System. Laswell is just as deft at propelling rock, pop, funk, metal, and jazz artists beyond their comfort zones. He also works with musicians from across the planet, capturing them as soloists, within traditional group contexts and meshing them with artists from other cultures.

The list of legendary names Laswell has collaborated with is epic, including Laurie Anderson, Afrika Bambaataa, Ginger Baker, Herbie Hancock, Whitney Houston, Zakir Hussain, John Lydon, Motorhead, Pharoah Sanders, Tony Williams, and John Zorn. The lesser-known, boundary-breaking names are no less important, such as Last Poets, The Master Musicians of Jajouka, Sonny Sharrock, Jah Wobble, Bernie Worrell, and Hideo Yamaki.

Innerviews met Laswell on his home turf in New York City at the Landmark Tavern in Hell’s Kitchen. It’s one of his favorite hangs, with a room on the second floor the owners provide for his use on request. The Irish pub originally opened in 1868. Many believe it’s haunted. A Confederate Civil War veteran was knifed to death in a fight and died in the bathroom next to the space where this interview was conducted. “I wouldn’t go in there if I were you,” said a genuinely concerned Laswell to Innerviews.

A gray vest provides the only color variant in Laswell’s otherwise all-black attire, including his signature knit cap covering his salt-and-pepper, shoulder-length hair. He’s a man of quiet intensity. Laswell pauses thoughtfully throughout our two-hour discussion. He offers serious reflections on the state of the world, politics and the music business, including his ever-expanding online platform that serves as an important outlet for new releases and reissues. His work with the likes of Last Poets, Public Image Limited, The Ramones, Wadada Leo Smith, Bernie Worrell, and Yemen Blues also serve as deep-dive topics.

Let’s start with the big picture view and how your current work is dovetailing with the business realities of 2017.

I’m just surviving. I don’t necessarily have a philosophical framework for moving forward. I’m just trying to sustain what I do. It’s been a little slow, but at the same time, I’m in touch with great musicians and somehow making it. I used to get a lot of money from labels and that doesn’t happen anymore, but there are investors and opportunities. Live shows are slower too. Europe is a little tighter than it was before and Japan is really difficult. That’s due to a serious radiation problem related to Fukushima, but no-one ever talks about it. People don’t talk about anything at a serious level these days. As for the Middle East, we can’t work there as much either. I had offers to go to Iran but the money wasn’t happening.

What’s your approach to making things happen today?

I’m a professional “waiter.” [laughs] I don’t struggle to raise money. I just wait. Things always happen. Always. It’s okay. I can get through things. I’m not a good hustler or con man. I’ve been around the greatest hustlers and con men who ever lived in this business, but I wasn’t influenced enough by them to learn how to do what they do. The film director Alejandro Jodorowsky once talked about a film he was making in Mexico during which the money ran out. The crew hadn’t been paid in months, he couldn’t pay for equipment and people were leaving. So, what did he do? He said “I’m going to go into my room and look at the wall. I’m going to wait like the Buddha and someone will show up with a newspaper and inside of it will be $300,000, which is just enough to cover everything.” A friend of his, who was the president of a bank, did show up and brought him $300,000, but not in a newspaper. So, I’m still waiting for something like that to happen. [laughs]

You’re using an online platform to release exclusive music, prolifically. What makes that approach attractive to you?

It's like thinking about making music available like a gallery. It’s more about fun than business for me. It’s nice to have a lot of things in one place. It’s a good feeling, but it’s very small money. Previously, I never liked the idea of a digital label. It felt like a cop-out, like you can’t get your record out, so you’re so desperate you have to do it that way. For a long time, I didn’t get it. But with Giacomo Bruzzo’s input, I decided to put up a lot of albums and it feels really good. We’ll maybe create better cover art for an album, perhaps resequence, remaster or re-EQ it, write up the notes, and then the next day it’s out. That’s great. Maybe that’s what it should have been like all along instead of waiting six months to release and promote an album. I have an amazing archive of live stuff that you’ll see us continuing to put out on there.

Are you still attached to physical media?

Not as much as I used to be, because what do you with it anymore besides give it to people? I’m not sure it’s as relevant as it once was. I never thought I’d say that, but I see the reality of things. There are very few record stores today. Other Music here in New York is gone. Bruce Gallanter’s Downtown Music Gallery is the only one left.

Some people think repackaging, renaming and resequencing previously-released albums is controversial. What’s your response?

It’s a nice feeling to give something better artwork, edit something more effectively or differently, master something with higher quality, or sequence something more the way you intended it. If you made the music, it’s yours. Nobody can say anything. Let’s go back to the Future Shock album. I remastered it and did a 5.1 surround mix of it for Sony. It came out under Herbie Hancock’s name, but I put it together. For this version of Future Shock, I went back to my original sequence. It came out with someone else’s track order. Remember, I made the original record. I came up with the track titles. I did everything. But Sony said “Oh no, you have to go back to the original sequence.” I said “No. This is my sequence. This is the way it was originally intended.” They said “No, it’s not the original sequence.” Insane.

When they made the original pressing plate for side B of Miles Davis’ Kind of Blue, the tape machine was running slower than it should. So, the music was a half-step of a note out from what the original recording was. But it was pressed up and printed, and that was the record for the next 40-50 years. When they went back to remaster it decades later, they discovered the problem and changed things to the right pitch. What did the record company, which again is Sony, say? They said “Oh no, we have to make it sound like the original because that’s what people know.” And that’s even with knowing full well the original was a mistake. There’s no room for purists in this spontaneous music thing. There’s no room for them, because the whole idea of being a purist doesn’t apply at all.

Why didn’t the Future Shock 5.1 remix come out?

It’s because 5.1 remixes didn’t take off in America. I have a whole record called Technovoodu: Astral Black Simulations that combines a lot of Herbie Hancock’s electronic stuff that I did for Sony that didn’t officially come out, either. It will eventually. Sony paid a lot of money for that and then nobody knew what to do with it. Bob Belden passed away. He was the only one fighting for these things to happen. Other guys like Steve Berkowitz who were very important are also no longer with Sony. So, the whole thing’s corporate now.

Is there specific criteria for what you’re choosing to put out online?

No, it’s a grab bag. It’s whatever we think people might be interested in. If we don’t make this music available, nobody else is going to. There’s nobody home at the record labels anymore. There’s a lot of corruption and stealing involved with those labels. It’s very complicated. I grew up with the real music business criminals—some of the worst criminals imaginable. All big music industry guys I’ve worked with since the ‘80s. But those guys also made this business. It wouldn’t be what it is today without them. Did they steal? Definitely. Did I steal? For sure. But we made things happen.

Explain what you mean when you say you stole.

I took the money as I went. I helped a lot of people. I’ve disappointed some people, definitely. I took from the corporations and gave the money to other people, Robin Hood-style. I’m still doing it. But there are fewer corporations to take from. Some of the criminals in the business are the ones to get things done. You could make a list of the 20 biggest music industry criminals and look at it and realize they built the whole system we’re dealing with. I’m talking about real music. Not entertainment. They made some very important music happen.

Some people feel the old label system had no value. Clearly you feel otherwise.

In retrospect, they were so stupid that I could actually get a lot of money from them. I would take that money, take my time and make great work. On a more selfish and comedic level, I was able to have fun. We did crazy shit in the ‘80s. I’d say “Well, we’re going to Japan. I need to bring some people.” The label would say “What do you mean some people?” I’d say “Oh, you know, I need 10 people. And we need first-class tickets for everyone.” [laughs] It was nuts, but it was fun and at the end of the day we delivered.

I remember when Chris Blackwell sold Island to Polygram at the end of the ‘80s for more than $300 million. I went to visit Chris the next day at his house in Central Park. I had no idea what I was going to say. I was making it up in the cab on the way. I had been up all night with Peter Brötzmann, Cecil Taylor and Nick Nolte in an after-hours bar. We were there until noon. I was completely wasted, but I arrived at Chris’ place and said “I have this idea. I want to do this label.” That label was Axiom. He just got all that money and he made Axiom happen in 1989. None of it would have happened without him. Once I got the money, I was dead serious about the label. We did great work. But its beginnings were pretty abstract and it was related to that old system.

Jean Karakos was the guy that funded the Celluloid label. There’s a lot I can say about him, but he did find the money. There were some serious financial issues working with him after the recordings were made, but he always paid to make them happen. It was a similar thing. I’d say “I want to go to Paris and take Bernard Fowler and DST.” He’d say “Go to Paris.”

The important thing is we didn’t just take money and not do anything. People were on drugs. Some were alcoholics. People were dying. But shit got done. It’s different now. There’s nothing wrong with different, but you have to navigate and find a new way. There’s no shortage of money in the world. You have to hope some of those people like what you do.

What do you make of the new tech criminals running streaming companies, paying artists in fractions of pennies?

Oh, that’s lightweight. I’m not talking about numbers, but in terms of people’s character. I’m talking about Capone, Geronimo and Malcolm X types. I’m talking about real people. These new tech guys are just kids and music is fun to them. They’re adolescent criminals. They’re like petty thieves with big money. The guys I’m talking about are pretty heavy. I was there. I knew them personally. We’re talking full-on gangster people. Some of them did prison. Some of them ran drug empires. Some of them stole from other business worlds. But I wouldn’t be here without some of those guys. They had financing. Some of them were even thoughtful. They took care of things when I needed them to. One guy even went to prison for what he did in the record business. Can you imagine that?

The Road to the Western Lands is a particularly interesting reconfiguration of your work with William S. Burroughs from Material’s Seven Souls and Hallucination Engine. What made you want to create this new iteration of that output?

I pulled Burroughs out of Seven Souls and Hallucination Engine because I thought it would cater more to people who love William S. Burroughs. In 2014, we celebrated what would have been Burroughs’ 100th birthday with a show at John Zorn’s club called The Stone. I did all the music I made using Burroughs’ voice. Then, I met the guy who runs the Burroughs estate and we discussed that it would be cool to just isolate my tracks with Burroughs as an album.

The Western Lands is very great work. It’s the third of the Burroughs trilogy that begins with Cities of the Red Night and continues with The Place of Dead Roads. He did it towards the end of his life. It came out in 1987. The Seven Souls album goes back to 1989, which is a long time ago. But I think I accomplished something very effective as far as putting his voice to music goes. A lot of people have tried to do that previously. Elliot Sharp and Steve Buscemi did an album called Rub Out the Word, which was interesting. But the rest of them aren’t that interesting to me.

What elements of Burroughs’ work do you most connect with?

Early on, I realized my interest in Burroughs’ work was less to do with the cut-up novels and more with the documented research and investigation of the human condition, technology, control, travel, dreams, drug culture, shamanism, and Hassan-I Sabbāh. Books like The Job, The Electronic Revolution and especially, The Third Mind with Brion Gysin were particularly important to me.

Through Burroughs, I began to discover Gysin and later Paul Bowles. When I realized they had all been living in Tangier for many years, I decided I had to go there. They were my initial inspiration for traveling in North Africa—way before the music recordings.

As for integrating Burroughs’ work into the music, it’s not about the history of a literary collaboration, but rather the complete fusion in a praxis of two subjectivities that metamorphosize into a third. From this collusion, a new author emerges—an absent third person, invisible and beyond reach, recording the silence.

Where did the Burroughs vocal for Material’s “Words of Advice For Young People” come from?

I took it from something Hal Willner did for Island. I did a remix for a Burroughs record he did called Spare Ass Annie and Other Tales. So, I had the vocal in my archive and put together a new track, without any business involvement. Axiom was connected to Island at that moment. Hal’s record was on Island, so everything kind of worked.

The On Brion Gysin EP you created with the late Ira Cohen is another interesting recent spoken word release. Tell me about its history and intent.

I did that with Ira a long time ago but it never got released. I thought it was Ira at his best. He loved Brion Gysin and I thought it translated very well, so that’s a solid intent. Gysin meant a lot to me as a painter. He was one of the most underrated painters in history. One day people will recognize that. Maybe they’re starting to. Gysin’s most famous piece, Calligraffiti of Fire, is a combination of Arabic and Japanese calligraphy. I was always very taken by it. A friend of mine in Ireland bought it for $500,000, which was the biggest sale of a Gysin piece. I thought he was way ahead of everything. It had more to do with Rammellzee and Futura than it did with classic painters. It was very hip and will be 100 years from now.

Musically, the On Brion Gysin EP is atmospheric and involves me trying to be supportive of Ira. He spent a great deal of time in Morocco, as did Gysin. Ira had a book publishing company in Kathmandu and was putting out poetry by Paul Bowles that nobody even knows about. He always tried to champion Gysin, who struggled and didn’t have it easy. Gysin died in 1986. I never met him, but I’ve worked with a lot of people who knew him.

Another intriguing example of music that has been renamed is The Map is Not the Territory, first credited to Autonomous Zone in 1991, but now reissued under Tokyo Rotation Origins. Tell me about that decision.

In 2004, John Brown, who has done cover art and been involved in a lot of other projects with me, helped me start Tokyo Rotation. It’s a club residency that brings together a diverse configuration of Japanese musicians. We put them all together and they don’t know each other previously. But they meet and start working together. But the Tokyo Rotation idea goes back much further into the early ‘80s and The Map is Not the Territory reflected those beginnings. It had Hideo Yamaki, Yukihiro Isso, Toshinori Kondo, Akira Sakata, and Haruo Togashi on it, along with Anton Fier, Peter Brötzmann and Foday Musa Suso. I work with a lot of these people today. So, I thought it was more fitting to credit the album to Tokyo Rotation Origins.

You just completed a new Last Poets album for release in 2017. What’s your perspective on Last Poets’ importance during this brutal political era, with American Republican leadership embracing fascist and racist socio-political policies?

Last Poets offer the perfect soundtrack for the times. We’ve got Donald Trump as president with no possible support from the Black community, where kids continue to be murdered by police. It’s going to be nuts, now that he’s in office. Last Poets are the voice of dissent. They’re before hip-hop or rap. We’re talking about street culture. They’re the voice of the street talking to the rest of the world.

When I was in 11th grade, I played in a band that only covered the first Last Poets album from 1970. It had drums, percussion, bass, and three vocalists and all we did was that original album Alan Douglas put out. So, I go back that far with them.

Describe the production approach you took for the upcoming Last Poets album.

We all decided we didn’t want to put a lot of instruments on the album and go back to the origins of Last Poets, which was hand drum and vocals. It’s more of an African thing. So, that’s what we did. There are a few horns on the album. Pharoah Sanders and Graham Haynes play on it. But it’s not about having big names on the record. It’s about the rhythm and the narrative that is relevant for the times. There’s no synthesizer, bass or drum kit. We chose not to orchestrate the album. We went back to the original street music sound. Abiodun Oyewole is like a CNN anchor on the album. Umar Bin Hassan goes for the more emotional element like Coltrane or Hendrix. It’s a very different album. Last Poets were always very different. The new album feels right. It’s a strong record.

Do you find it surprising that today’s hip-hop artists rarely engage in meaningful political commentary?

The hip-hop community is about business. Business doesn’t have a political voice. It’s all about numbers. In the ‘80s, we had Public Enemy as a franchise. They used politics in a commercial way for business. I don’t think it was real. Last Poets are real. Public Enemy was a business. They had the right intentions and brought up important issues, but at the end of the day, they weren’t ready to fight for them. Abiodun Oyewole of The Last Poets went to North Carolina and robbed the Ku Klux Klan. He went to prison. They were militants. That’s very different from Public Enemy being nice to their record company so they don’t lose their deal. They also had Flavor Flav in the group, who is a clown. It’s not serious.

Public Enemy was once a daily part of your life in the early ‘90s. What do you recall about that era?

I once had a studio called Greenpoint in Brooklyn. For two years, Hank Shocklee of Public Enemy rented my studio every night and would bring in Public Enemy. We would be working during the day and at night, Hank would bring in Chuck D and Flavor Flav. I would have guys like Buddy Miles and Eddie Hazel in the studio and Flavor wanted to meet all these guys. They hooked up a little bit but nothing really came of it. Hank covered the rent for two years. They were always on time with payment. Everything was straight.

I remember Hank holding auditions and they would bring in these kids, set up a 16-bar loop, and have these kids rap over them. One of those kids was Nas. That’s how he got started. I played in a band with Nas’ father Olu Dara, the trumpet player. I once ran into Nas at the airport when he first started and I said “You know, I used to play in a band with your dad. I put him on an Afrika Bambaataa album called Shango.” Nas always thought it was cool his father played on a Bambaataa record.

A lot of hip-hop artists claim Last Poets as an influence, but it’s rare you hear the actual impact.

It’s like saying I love John Coltrane and then getting him confused with someone else. When people say that, it’s not deep. I found it interesting that Kanye West was very interested in Last Poets. He approached them, they talked, but he never did anything with them. I just sent Kanye the new Last Poets album.

What do you think of West’s music?

I like some of the production. I think the music is a little Donald Trump. Kanye is skiing with the Kardashians in Colorado. It’s a White thing, not a Black thing.

In 2012, you released Tuwaqachi: The Fourth World, an alternate soundtrack for the film Koyaanisqatsi. What made you want to create new music for a movie with such a revered soundtrack?

Because the revered soundtrack didn’t work with the film in my opinion. It was Philip Glass playing these repetitive parts and I didn’t get it. I thought the movie was much darker and full of all kinds of decay, dissonance and distortion. Glass’ soundtrack never made sense. I think that soundtrack was on there because Philip’s name helped get the film to the public. I knew Godfrey Reggio, the director, and met him in his studio and said “Let me try to do something different.” So, I did and he loved it. Last February, I performed a live soundtrack for Koyaanisqatsi at the Drawing Center in New York, so there was interest in this new score.

You’ve worked a lot with Wadada Leo Smith lately. How did you first connect?

There’s a label in Finland called Tum, run by a guy named Petri Haussila who finances all the records. They work in my studio a lot. They asked me if I’d be interested in working on music for the label. They knew I was working with Milford Graves and suggested I do something with him. I said “No problem, I can do a duet with Milford.” We did that very easily and it came out as Space/Time - Redemption. Then I met with Wadada at a session at my studio with Jack DeJohnette. We talked and he called me to play on his record for Tum, which included a lot of guitar playing. Henry Kaiser and others were on it. But I didn’t think the production was going well. Henry’s parts were fine, but I didn’t think the other guitars were appropriate and the trumpet sound wasn’t right. So, I said to Wadada I think we can do better. He came over to the studio and we re-did almost everything, except Henry’s stuff and the drums. From that point, I started playing with Wadada live and it sounds like ambient country blues. The record that’s coming out isn’t jazz. It has a spiritual sound. We also got along as people, so since that point, we’ve done a lot of other recordings, including a duet album. There are six records in the can. I’m hoping they’ll put them out as a box, otherwise it could take a long time for this music to get released.

What makes Smith an ideal creative partner for you?

We have a conversational approach to our music. He’s from Mississippi, I’m from Illinois. We speak this unique kind of American vernacular. As Santana would say, “We’re not Bush. We’re the other America.”

Also, technique is one thing and learning about so-called music is another. But when you get to the point at which you play and are able to tell somebody a story, that’s when you know you’ve arrived. Unfortunately, it doesn’t happen when you’re young. It takes your whole life to get there. Wadada is telling stories. And when I play with him, I feel we’re both telling stories and that’s new for me.

At what point do you feel you started telling stories with music?

A couple of years ago. Previously, the rest of it was application, listening and referring. Lately, it’s not that at all. A lot of music in which I’m telling stories hasn’t come out yet. The music is more lucid and spontaneous than things I’ve done that are more structured. When you’re younger, things are more literal. Musically, you might be saying “A train goes by and it’s raining in the countryside.” But that’s not what I mean. What I’m talking about is music that is more natural and unstructured. You’re telling stories, but not in an obvious way. It’s about feeling.

What sorts of stories are you telling?

It’s hard to put into words. It’s about channeling memory and moving time around. It’s about taking a time from before you and putting it in the place of now. I don't have a graphic system of structure. But when I played with Wadada for the first time, I thought he reminded me about the South. I thought about rivers, Illinois, trains, and forests. And I didn’t know who Wadada was except for his work with AACM. Then I saw he came from Leland, Mississippi and I thought to myself “I’ve got it. It makes sense. I came from the country too—the South of Illinois. Whatever I got there, I brought it to New York with me because we don’t have that experience here.” In New York, you have to learn about music. In the country, you either play it or you don’t.

Another artist you’re working with a lot these days is Hideo Yamaki. Reflect on your multi-decade partnership with him.

I’ve known Yamaki since 1983 when he was playing with Toshinori Kondo and that’s how I met him. We did a lot of sessions for all kinds of music during the ‘80s, including pop and reggae, and it developed over time. He’s one of the biggest session musicians in Japan, but he’s not known in the same way Ginger Baker or Tony Williams are. But if it’s a hit pop record in Japan, it’s probably him playing. He’s versatile and unusual in that he can play anything. He’s very flexible, intuitive and spontaneous. As far as technique, there’s probably nobody quite like him and I’ve played with everybody. He’s got a thing that’s special. So, we’ve formed the Yamaki super PAC and we’re trying to push him out there and it seems to be working.

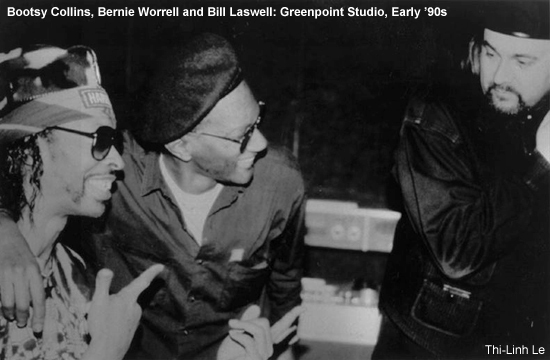

You had a very productive relationship with Bernie Worrell. Tell me what he meant to you as a person and musician.

He was very fragile. He never learned how to hustle or manipulate people. He was all about playing what he had to play and wanted to play. He was very special and unusual. Bernie’s story is very complicated, but it’s all good when he played the keyboards. He could be a mess and destructive, involving drugs or alcohol in multiples that would destroy most people. But when he played the keyboards, he became that person that was special and very versatile. It wasn’t just P-Funk and riffs. I put him in a lot of challenging situations and everybody liked how he approached them.

What do you consider the highlights of your collaborative recordings?

I did a solo record called Blacktronic Science with him that I thought he played very well on. That might be one of the best ones. He did a record for Rykodisc called Funk of Ages. I only did three pieces on it that have absolutely nothing to do with the rest of the record, but those three pieces, one of which is a Sun Ra piece, were pretty effective.

Your last two recordings with Worrell, Elevation, a solo piano album, and "Black Space Invocation," a solo organ piece are considered among his career highlights.

I always felt Bernie should do a solo piano album. I wanted to make it very ambient and have nothing to do with P-Funk or jazz. We discussed the idea that it was very important not to learn the music, that he should be hesitant, approaching the pieces as if he had no idea what’s coming next. It worked. Unfortunately, Elevation got marketed to jazz people. So, these jazz people would listen and say “When is he going to play the piano?” One reviewer even said “It’s like he’s hesitating and doesn’t know what he’s going to play next.” That was my concept. Brian Eno, on the other hand, loved it and couldn’t stop listening to it. I made it for thinking listeners. So, the statement holds. It’s there. It stands. "Black Space Invocation" is an organ thing we did a long time ago, which I thought was very dark and interesting. I just wanted people to hear it.

Do you think Worrell ever got his due?

Probably not. Did he get paid for it? Definitely not. Everybody knows his sound but nobody knows him. There was a crazy movie some kids made on him called Stranger on Earth. It’s kind of obscure but worth seeing. He doesn’t speak in the whole movie, except for one moment when he comes out of a trailer at a rock festival and the wind is blowing. He goes “A minor 7.” He knew the key of the wind. In the movie, David Byrne says he’s a genius. Bootsy is diplomatic. I’m the last one interviewed in the movie and they ask me “What’s his legacy?” And I said “Nothing. He has no management. He has no publicist. He has no business. He has no label. He has no-one really helping him that makes any sense. His legacy is nothing. You’ll forget him like everyone else.” And that’s the end of the movie. It’s very dark. But it’s the truth.

Does a musician have to have those things to have a legacy?

They don’t hurt. Yeah, I think you do actually, unless you’re a real hustler. George Clinton doesn’t have to worry about not being George Clinton. He’s going to be George Clinton and he’ll get credit for shit he hasn’t even done. Same with Bootsy. Recently, I was at the Smithsonian and they have an African-American museum which looks incredible. In the middle they have the original P-Funk mothership that George would walk out of at shows. They have a statue of George and Bootsy, but there’s no Bernie. And to me, Bernie was very much a part of the sound of P-Funk, more so than Bootsy, actually. But he’s not there.

Talip Ozkan’s The Dark Fire, a 1992 solo saz album on Axiom was just reissued as an online exclusive. I consider it one of the best albums in the Axiom catalog. How did that opportunity come about?

Nicky Skopelitis was obsessed with Turkish music. There were several Turkish saz and oud players we were considering, including Munir Bashir, but Talip’s name kept coming up. We said “Let’s do it. Talip lives in Paris, so it’s easy. We’ll record the album there.” Oz Fritz was the engineer.

I think Talip’s album is solid. He was a great musician who gave a good performance. He seemed to be happy. We did it very professionally and that’s a given. It’s the same with all the African stuff. It has to be done well or you’re wasting your time because it’s all been done before. There are guys who still go to Morocco with cassette and DAT recorders and it’s pointless. You can’t hear anything.

Describe what you bring to the table as a producer when you’re recording a musician making a solo instrumental album made up of complete takes.

You just make sure you have a very clear sound and that the musician is comfortable, so they’re going to perform and play well. If there’s anything not kosher about the situation, you’re going to feel and hear it. It’s not a big job, but you have to find the money, do the traveling and ensure the musician is content and playing well. That’s why when Real World started, I thought it was strange for them to record all these great musicians in a big studio in Bath. My concept was to go to where the people live, even if it means recording in the desert. You’re going to get the real thing. It’s not going to be people confined to a weird environment they’re not used to.

How did you get involved as producer of the Yemen Blues album Insaniya?

Shanir Ezra Blumenkranz is a bass player I knew from the John Zorn crew. I liked him and knew he played well. He worked with the band Yemen Blues and contacted me asking me if I would be interested in working with the band. I’d never been to Israel, so I said yes, we’ll go. I took two engineers and it was very easy to work with them. I mixed it here. The main guy is Ravid Kahalani and he’s Yemenite, but a Jew, which means he’ll never be able to go to Yemen. He’s very charismatic and a real entertainer.

The album has your production fingerprints all over it.

That’s because they let me work. Some people don’t and you don’t get that freedom. There are a lot of records that didn’t happen because people are suspicious. They think I’m going to change their sound. The Yemen Blues guys wanted a new sound. They were very cooperative and open, and that’s what it takes to get a good result.

What can you tell me about what enables you to mesh disparate traditions together, such as the Israeli, African, funk, pop, and hip-hop elements of Insaniya?

I don’t think there is a system. It’s spontaneous. I’m grateful that I followed the way into improvisation because it applies to everything, including this conversation. I’m able to play to 20,000 people with a group of people who’ve never played together and invent in the moment. Some people will say we put on an incredible show. Others will say they hate it. But I’m grateful because improvisation gets past the stiffness, redundancy and repetition of something that sounds like something else. Most producers don’t play instruments. So they don’t even know what I’m talking about right now. But when you have that experience and you’ve gravitated with this improv idea, which is about telling stories as opposed to playing notes, you gain a weird advantage. If people let you express that, you can do pretty effective work. But if people are blocking you as a producer and say their concept is that their demo is very important or they want to have a hit record right away—which isn’t going to happen for anybody anymore—it’s not going to work. With Yemen Blues, I got lucky because they’re open and not uptight.

You’re considering a new Tabla Beat Science project. Tell me about it.

It’s just an idea at the moment. Last year, I met with Zakir Hussain about trying to get back to my original idea for it, which was more of a beat-oriented project. The original Tabla Beat Science sound had a lot to do with the people that were around, including Sultan Khan. We did very successful gigs and documented three recordings during the short period of time we were together. If we move forward with a new Tabla Beat Science project, it will be more rhythm related, using Zakir, Trilok Gurtu, Hideo Yamaki, DJ Krush and special guests as soloists like Pharoah Sanders and Carlos Santana. I don’t think Tabla Beat Science has to be what it previously was, with an Indian classical focus.

Jason Corsaro, Oz Fritz and Robert Musso have been at your side engineering myriad projects for decades. Describe the expertise they bring to the table.

Engineering is a very special skill and requires special people. Oz is more on the esoteric side of things. He has experience with different techniques, but he locks into the spiritual part of things and takes his time. He’s very articulate about what he wants to do. Oz was first an assistant engineer and I would bring him to sessions with Bootsy, Maceo Parker, and Sly and Robbie. Sometimes, a weird project like William S. Burroughs would come through. He connected to all of that and it probably helped his development. Oz is also really good at live sound. If I’m in control of a concert, he’s always there, including Master Musicians of Jajouka and Tabla Beat Science shows. Robert comes from the big studio world of working under pressure, dealing with big producers and artists. So, he’s coming from the technical side of the house. Jason Corsaro is a little bit of both. He defined the ‘80s with his work.

Klaus Schulze and Pete Namlook’s Dark Side of the Moog releases have been compiled into three new box sets. What do you recall about working on those albums?

I’m on a few of those. I remember very little. It was all done so fast. I did some of it at Pete’s place in Germany, but it wasn’t about quality control. It was more about “Sounds great! Let’s go have dinner.” [laughs] It wasn’t a lot of work. I only talked to Klaus once on the phone. I never met him. I just played on the albums.

What’s your perspective on Namlook’s musical aesthetic and your contributions to it?

He was ambitious, for sure. He wanted to create a massive catalog of music, which he did. He was very opinionated and knew what he liked. He started out as a guitar player while he was working at a bank. He used to take his guitar and go practice by the river. He started to realize his sound was very interesting, which was the sound of water moving. He was really into jazz-fusion and Return to Forever, but he wanted to get away from all of that. He stuck with the sound of the river. That’s why I did a piece on the Die Welt ist Klang Namlook tribute album called “By a River” with Bernie. Pete got deep into the ambient, electronic and beat-oriented stuff. I never worked much on that stuff. Pete would say “Play it” and then “Ah, it’s great. Let’s put it out.” It wasn’t a lot of work. I like Outland II which we made in 1995 a lot though. It’s interesting because it has Mongolian music samples on it. I had played in Mongolia in 1994 and recorded all this stuff that we used on it.

You were touring with the Flying Mijinko Band in 1994 through Mongolia, China and Uzbekistan when you recorded those samples. Tell me about that band and the experience of touring those areas.

It was a three-week tour through places including Beijing, Hohhot, Ulaanbaatar, and Samarkand. It was nuts. It came about because Akira Sakata worked for years with the Japan Foundation trying to make this tour a reality. It had probably 40 people traveling country-to-country with all the techs, sound people and film crew. I couldn’t take it after a while. When we got to Uzbekistan, I said “I’ve got to go back to New York for a little while. I can’t deal with this shit.” Everyone was camping out in the woods. We were being fed meat with fur on it. So, I bailed for a few days and then came back. We did go to Mongolia. It was tough. The whole thing was crazy.

How did Sakata convince you to do the tour?

I wasn’t paid great, but I figured if I don’t do this tour now, I’ll never go to these places. I read about Samarkand and how Gurdjieff made a pilgrimage there to meet Sufi masters. So, I said, yeah, we have to do it, but it was brutal.

A live album, Central Asian Tour, and a documentary came out of the experience. How do you look back at the music that was performed on the tour?

I don’t think the music was anything special. It was Foday Musa Suso, Aiyb Dieng, Nicky Skopelitis, Anton Fier, and Sakata. Suso didn’t think Fier could play drums, so there was some bitter, weird personality stuff going on. But we always played with the indigenous musicians wherever we would go, which was interesting.

What can you tell me about the making of the Dubopera album Risurrezione with Japanese opera star Masahiro Shimba?

Dubopera is both complex and simple. Yoko Yamabe, my partner, knew Shimba, who wanted to do something different. He happened to have an investor who was pretty huge. So, he brought forward this idea of doing something unusual with opera. I don’t particularly like opera. It’s pompous and old, but they had an insane budget and I thought it would be a challenge to do something with it. I was able to hire people and do something ambitious because there was that budget. Without that budget, it couldn’t have happened. We were able to navigate and spend time on the album. A lot of people got paid and it was profitable for everyone. It was a commission. Sometimes you do it because it’s a job and you do the best job you can.

This wasn’t the first opera record I did. I previously did an opera record for Alan Douglas called Operazone, which I kind of enjoyed. It was Alan’s wife’s idea. She was into opera, so she picked mostly famous Italian composers, like Puccini, to work with. But it didn’t have vocalists. It had instrumental soloists instead.

What’s your perspective on Trump's ban on immigration from multiple Muslim nations and its effect on global music projects?

The so-called "Muslim Ban" will absolutely affect the ability for global music projects to go forward. It's going to affect travel in general. It will also affect human lives—Muslim families’ existence and any possible future. It’s random, racist, evil, and unbelievable. Fundamentally, it is clear this is White Supremacy. One solution could be the emergence of intelligent revolutionaries with advanced skills. We live in times of horror.

Public Image Limited’s Album from 1986 was just reissued as a multi-disc box set with remixes and outtakes. Provide some insight into the making of that record.

That was a tough one because we’re talking about the ‘80s here. In the ‘80s, a producer was an outlaw in a way. I was kind of registering for this situation without knowing what I was getting into. But it was a situation in which I could do whatever I wanted. This was an era when there were no budget limits. I had met John Lydon previously, when we did “World Destruction” with Afrika Bambaataa. We kind of knew each other and agreed to make a Public Image Limited album for Elektra. The money was right and we moved ahead.

Lydon arrived in New York with a band of kids from LA. When I say kids, I really mean kids. They were 20-somethings and they were terrible. We went to Power Station and attempted to record them and I realized within five minutes that I needed to do something different. I decided to bring in Ginger Baker from Italy. I said “Why don’t you come to New York to work on a project?” I didn’t tell him it was for Johnny Rotten, who he was into. I also got Tony Williams.

So, people were lined up to play. I even recorded three pieces with Tony Williams before the kids arrived. He was on “Rise,” which carries the record. That was done before they even got there. But when they did get here, I started pushing different musicians into the room. I brought in Malachi Favors from Art Ensemble of Chicago. I took the kid on guitar into a bar and said “This isn’t going to work. We’re going to continue. You probably need to get on a plane.” The guitar player said “Well, I play guitar in the band.” I said, “We have this new guy. You probably don’t care about him, but his name is Steve Vai.” Lydon’s band said they couldn’t compete and they all drifted.

After that, for about two weeks, I worked on the record without John. He had no presence in the studio. You can read his book to see his account. It makes all kinds of claims like Miles Davis came and played and we couldn’t use it. That’s not true. Ornette Coleman came by. He was a friend. He was just listening. He said “Well, when you use the voice, you have to make it sharp.” So, I told Musso to put up the vocal and make it sharp. [laughs]

How much of Album is you?

Oh, a lot.

Is your contribution at Future Shock-level proportions?

Almost. Lydon had a couple of riffs and some titles. I had Bernard Fowler double Lydon’s vocals a lot. Bernard knows how to copy anyone’s singing. We did that with a lot of rock singers. Sometimes we wouldn’t even put his name on things. We’d just make the vocal sound better. He doubled Lemmy on Motorhead’s Orgasmatron, which I produced, and Lemmy didn’t know it. But Lemmy thought it sounded great. Lydon knew Bernard doubled him. If you listen to the chorus of “Rise,” it’s Bernard.

Were you butting heads with Lydon when he was around?

Oh yeah, the whole time. But when he heard the mix, he loved it. So, we were good. I even started a second Public Image Limited record with him, but we had a huge blow up, so I didn’t do it. The next year, Lydon came back with another band under the Public Image Limited name, with John McGeoch from Magazine, who was a very influential guitarist. I don’t think U2 would exist without him and Keith Levene. So, I met the new band and said “It’s going to be the same shit. I’m going to have to fire the band.” So, it was exhausting. John said they were really into Turkish music. I did a lot of research into Turkish music before and they didn’t sound like Turkish anything.

At the end, they were playing in the studio and I said “I’m out, let’s meet tomorrow.” So, I meet John at a bar in the West Village. Tony Meilandt, who was Herbie Hancock’s manager, was with me. John and I argued brutally the whole time. At one point, I was getting ready to leave and there was a kid walking by. The back of his jacket had a Sex Pistols logo on it. I said “You see that? You used to mean something. Now, you don’t mean shit. We’re out of here.” And I left him at the bar.

Let’s go back to Time Zone’s “World Destruction” single from 1984 with Lydon and Afrika Bambaataa. The message is completely relevant for the Trump era. Do you agree?

Lyrically, it still fits perfectly with the times. Musically, it holds up, except for certain tones and drum things. It was done really quickly. It’s just a programmed beat, very minimal bass and Bernie on keyboards. The way it happened is Bambaataa called and said “I want to make this record with a heavy metal singer. Do you know Def Leppard?” [laughs] I said, I know who they are but I don’t know them. What about Johnny Rotten? Do you know him? He said “Yeah, that would be alright.” So, it was Bambaataa’s thing. I knew Lydon at that time and it took him five minutes to do it. There’s a really crazy video for the song with Lydon in his hotel room. You see them going in to film the video and he’s kind of drunk and doesn’t come out of his room. So, they have to shoot it around his problems.

What was it like to produce The Ramones for their 1989 album Burning Brain?

[laughs] I knew The Ramones and I couldn’t say no. I had to find something interesting about it. I thought it would be funny and easy. It’s simple music and I can’t do much with it, but I tried. I probably went way too far on a lot of things. I had the idea of doing this multi-layered thing which was more like AC/DC but that didn’t work for The Ramones. At the end of the day, I think I destroyed Johnny because he just wanted to have one guitar track and I had 50 guitar tracks, so they probably didn’t get that. But I think the record was pretty good. I was pretty happy with it. All of those guys have passed away except for Mark. I just wanted to do it for the experience. I did a lot of projects like that. I didn’t know The Swans or really what to do with them. But the records do well. The artist doesn’t always like it, because even when I’m restrained, I always end up doing something that’s not quite what they’ve been doing.

Swans’ The Burning World from 1989 is still considered one of their classic albums, despite the band being unhappy with it.

If you talk to Michael Gira, who I’m a friend of, it’s his least favorite record. But I thought it was their best record. There’s another one I liked called Children of God, but I didn’t like the sound of it. I like Gira and I thought there were good pieces and we did a good job. We could have had better musicians, but I used Trilok Gurtu and Fred Frith on it. I thought I brought things up a little bit.

There’s a pattern throughout your career when you produce some established bands. There’s conflict in that the artist doesn’t particularly care for what you did, yet the album sells well and stands the test of time with listeners. What do you make of that observation?

There are a lot of projects like that, but they’re mostly rock bands. I’ll also say it’s White bands. That’s been my problem the whole time. Even when I played in a rock band growing up, the White people just argued all the time. When I played in a Black band, everybody is cool and there was great music. It didn’t change as I started doing all the work. So, there’s always trouble with these bands. It’s a little anal. For the Public Image Limited album, we fought the whole time. I kicked Lydon out for most of it and that album was a great success. Even John knows it was a great success.

You worked with Sonny Sharrock on many projects during the later years of his career. How do you look back at the music you made together?

I brought Sonny out of retirement. We played together for years and made a lot of records. Ask the Ages from 1991 is a classic. Faith Moves with Nicky Skopelitis from the same year is also really good. How many artists do you know that did their best work at the end of their life? I always say Sonny did, because Ask the Ages was his best record.

Sonny was a natural. I knew about him when I was 14. I saw him play at the Newport Jazz Festival when I was 15. He was with Herbie Mann, who I don’t think much of. It was a day job for Sonny, Miroslav Vitous, Billy Cobham, and Roy Ayers. He had great musicians and he was paying them four or five times more than what was typical at the time. They all turned down Miles Davis, because they wanted to be paid. They were with Herbie 100 percent for the money.

Those Herbie albums are straight-ahead flute melodies and usually Sonny soloed at the end of the piece. It would be like noise. I remember playing those as a teenager. People who didn’t know that music would go to the record player and lift up the needle because they thought there was dust on it. But what they were hearing were Sonny’s solos. [laughs]

I remember being at the airport with Sonny once in Detroit. Ronald Shannon Jackson and Peter Brötzmann were there too. We saw Herbie at the airport. He was in a suit and tie with a trench coat and briefcase. I said “That’s Herbie Mann. We have to mess with Sonny.” So, we got Sonny and he came into the bar and sat down. We brought Herbie in, who was standing behind him. I said “We have someone you should meet” and Sonny turned around and saw Herbie. It was the first time I ever saw Sonny lose his composure. He had been with Herbie for years and hadn’t seen him in a long time.

I admit, I’ve wondered how Mann managed to put such amazing lineups together.

The musicians needed the money. That’s how. Sonny told me about how he and Miroslav once went to Miles’ house on the West Side. They pulled into his driveway and knocked on the door. The night before, Miles had been locked out somehow. He lost his keys. There was a woman staying at his place, but Miles had no voice, just that whisper. So, Miles is beating on the door and the woman thought somebody was breaking in. She called the police and they arrested Miles. When Sonny and Miroslav arrived, Miles is still filling out police paperwork and the woman is coming in and out. When they arrive, Miles says to the woman “Bitch, you didn’t hear me hollerin’?” And she couldn’t. He had no voice. Sonny and Miroslav were there because Miles wanted to hire them away from Herbie. But they said the money was nothing with Miles.

I did a tour in Japan in 1987 with a band called SXL. It had four Korean drummers, L. Shankar, Ronald Shannon Jackson, Aiyb Dieng, and myself. Miles was the headliner and there were four other bands. We would always open and then take the bullet train to the next city. The contracts for the shows would always arrive late, so Miles would never have them because he flew to each gig. He would have to get up really early. Because we were taking the bullet train, we would leave after him. So, all this paperwork would come to the hotel. Once, when we were leaving a hotel, the front desk said “Can we give you these papers for Mr. Davis? He left early.” Once, I took out the contract to see what everyone was making and his musicians weren’t making much. The gigs were paying something like $40,000 and some of the musicians were making $750 a week. But a lot of people jumped on the opportunity to play with Miles, but not Sonny and Miroslav.

What are your thoughts about the fact that we’ve lost so many influential musicians in the last two years?

But we haven’t lost the music. We just lost the people. If you didn’t see them every day, you wouldn’t notice. To me, Bernie isn’t gone. He’s around. He’s everywhere. If you go to a restaurant, store or bar, you’ll always hear him. We still get to experience his input. So, he’s not gone. He can’t be. It’s impossible. But I can’t call him up to say “Let’s do this concert” anymore.

You’re 61. Do you spend much time thinking about your legacy?

Yeah, all the time. I don’t know how to translate those thoughts to you though. There’s a guy named Tom Bojko that’s been working on a book about my work for over 10 years. That’s one way to communicate it. Tom came everywhere. He went to India twice and Japan with me. He wrote for the Japan Times newspaper in English. But I have no idea what’s going on with that book.

In terms of my health, I’m good at the moment. I was sick before with spinal meningitis, which was pretty serious, but I got huge support from Chris Blackwell and Giacomo Bruzzo, who helped me get through it. I try not to think too far ahead these days. I live pretty much day to day. I never planned any kind of career or longevity. I was just glad to be where I was. There’s a point at which I won’t be physically able to do what I do and that’s reality. I’m also probably alive because I have a kid. I should have realistically died in the ‘80s, but because I have a kid, I persevered because I didn’t want to leave him stranded.

What are you referring to when you say you should have died in the ‘80s?

Well, I tried everything that should have made it happen, but it didn’t work. [laughs] I made it, somehow.

There are more recordings being released now than at any other point in time. What’s your sense of the gravity of this moment in musical history?

The greatest music has either not been made or it’s being done right now. Everything else is just a setup to get there. You can say there’s not going to be another John Coltrane, and that’s true in a literal sense, but there could be a guy who plays a laptop who does something as important. Do you feel good about the experience, what you do and who you interact with? If the answers are yes, it’s all good. If there’s a no, perhaps you’re interacting with the wrong people. No matter what happens, I can’t say I didn’t have great opportunities and the chance to work with the most incredible musicians. To me, every passing second is the greatest moment for music.