Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

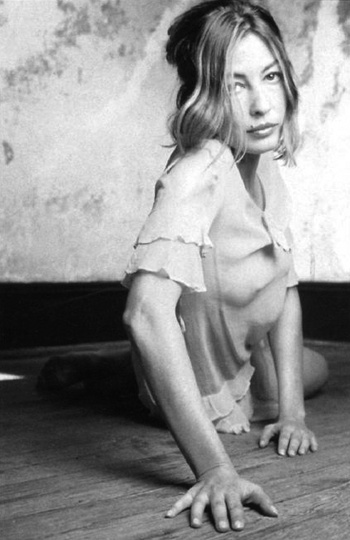

Lori Carson

Transcendent Moments

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1997 Anil Prasad.

New York City runs through Lori Carson's veins. The singer-songwriter describes her attachment to the city as "meaning you're a little bit cynical, intellectual and comfortable with dirt and grime."

That mindset permeates the lyrics of Carson's third solo disc Everything I Touch Runs Wild. The album's intimate songs explore a continuum of raw emotion with an emphasis on the darker and moodier side. The self-produced disc was mostly recorded in her apartment with sparse accompaniment comprised of low-key guitars, synth washes, string flourishes, and simple percussion.

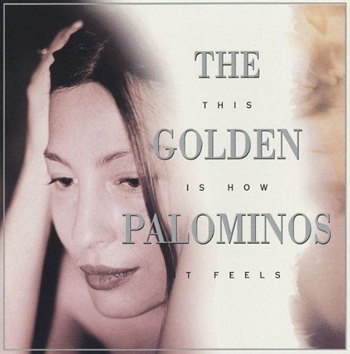

Carson's current sound is a significant departure from her critically acclaimed work with New York avant-rockers The Golden Palominos. Her association with the group resulted in 1993's This Is How It Feels and 1994's Pure. Led by drummer and producer Anton Fier and featuring luminaries such as bassist Bill Laswell, guitarists Nicky Skopelitis and Knox Chandler, and keyboardist Amanda Kramer, the discs merged rock, pop and electronica into a seamless whole. Carson departed from the group after Pure, but continues working with Fier who appears on her new disc.

Does the new album signify a declaration of independence for you?

I really think it has been a pretty gradual process over many years, probably starting with This Is How It Feels in 1993. Beginning with writing that record, I think I entered a new place and it did have a lot to do with growing up and finding my own voice. I feel that it has reached a really nice place in terms of doing what I want it to do and hopefully it's just the beginning and it'll get better. In terms of confidence, I just feel like I have a sense of what it is I'm aiming for when I sit down to write. And in performance, I also feel kind of connected. I'm pretty disciplined as a songwriter and wait for a moment of inspiration—not that I don't write when there isn't a moment of inspiration—but something clicked around the time of doing those Palominos records. I had a greater feeling of what it is I wanted to say and why I wanted to say it. It felt like something wholly developed suddenly. Part of that had to do with age, experience and years and years of doing that one thing, but also just being alive. There's nothing like life experience to make whatever you do, like your work, blossom. There's nothing like the experience of being a human being and being in your 30s. It all starts to happen.

What were some of the challenges you faced in producing the record yourself?

I think there were challenges not because of producing it per se, but because I was doing it in my apartment. There were challenges of being able to hear things well and to set everything up so that it sounded good. There are definitely problems on the lower end on my record. Recording the bass in my apartment probably was not a good idea. There are mistakes because I didn't know any better. That said, I don't regret any part of the process. I even like the aspects of it that are more fucked up. I think it works as a whole. There are aspects of production that are not terribly smooth. There are big sonic problems on the record. If you listen to the solo record before it, Where It Goes, which was produced by Anton Fier, that record sounds really amazing. It's sonically perfect. If you listen to my new record, it's sonically inconsistent. In a way, that adds to the charm or success of the record in terms of how I feel about it.

The apartment I recorded in was great. I no longer live there. I had lived there for five years and last year I bought a new apartment and moved out of that one. But really, recording wasn't that complicated. I had an apartment with 13-foot ceilings, plaster walls. It was a really nice, old building—a really open, loft-like space. I put everything into one-half of the space and used the other as a recording studio and rented many thousands of dollars of equipment and really set it up properly so it wasn't just me learning over a four-track or something.

You compared the sound of the two solo records. What about the lyrics?

I think the songs are a lot more minimal on the new record. The structure is broken down a little bit more in terms of song form and I think it's a lot less wordier of a record. There is a lot packed into the song train, but for the most part I say more with less as I mature as a writer. I think the songs on Where It Goes have a lot more structure and it's more traditional in terms of songs and form—the traditional singer-songwriter song form where you have verse-chorus-verse-chorus-bridge-chorus. There is a whole "you should" about songwriting I was raised with. Doing the Golden Palominos records broke that down for me. I can't even remember what I always knew about song form because things have changed so much for me.

Many point to your work as having an element of melancholy to it. Do you feel that's accurate?

It's interesting, because this record more than any other that I've worked on has not received the same feedback to that level. A lot of people say they hear a lot of joy on this record. I think most people write sad songs. The more important questions for me are "Does the song work? Does it make someone feel something? Is it an honest reflection of something and does it transcend that and become art? Am I making something that's beautiful and of quality?" Those are the things I think about.

Describe your relationship with Restless, the label behind your last few releases.

Restless hasn't really shown any evidence that they know what they're doing yet, but I'm forever optimistic. [laughs] To be fair, Geffen wasn't any better. They were horrible—they were worse. They didn't even try.

I stumbled on the secret many years ago. If you just do good work and keep doing it, you will build an audience. I go out and play live—that's what I do. You can't spend too much time worrying about the business side of it or it doesn't leave you much time for your work. It happens or it doesn't happen based on the way the business side is set-up—what the record company will spend on advertising, who's doing distribution, that sort of thing. It helps if it's a quality record, but I think sometimes that's secondary to the other stuff. So many records get critical acclaim but you can't find them anywhere and you never hear about them.

Provide some insight into the making of your first album Shelter from 1989.

I had been playing around New York starting in 1984—my first gig was that year. I was trying different things, adding different musicians, playing different clubs and really getting started and trying to figure out what the hell I was doing. I had sent off a bunch of flyers to my gigs—I was really consistent about doing that and a guy from a record company—I think it was Manhattan—came down and gave me a development deal. They gave me some money to do some demos and they recommended some music lawyers. So, I recorded five or six songs for that label and continued to play and I was really able to spend a lot of time working in which I wasn't waitressing three months in order to make enough money to pay the musicians to play a gig.

By 1986, I was getting more money to do this and was able to do it more regularly and demoed some more songs and the record company ended up not signing me at the end of the year. My music lawyer then sent off the tapes I had made to Geffen records and Gary Gersh who is now the president of Capitol Records. Gersh, who became my A&R person at Geffen, liked that tape, and he flew to New York to see me play and did that several times over the months. So, there were more tapes, more songs and more performances. Finally, Geffen signed me in 1988, I made Shelter in 1989 and it was released in 1990. It was produced by Hal Willner who had done all these compilations at the time. He did this Disney record called Stay Awake that I had heard and it sounded so incredible, like a musical journey, and that appealed to me. He was very unconventional, very New York and I thought he would be a great choice for that record.

I think it was a beginning period and I've learned everything since then. I think the record was a failure creatively and artistically. I don't think it achieved what anybody set out to do. It doesn't stand the test of time. I don't like the vocals. It's a first record and I think I just didn't have the experience to understand how to execute an idea, yet I was very stubborn, willful and tried to. I wouldn't let anybody else do it, so that's the result.

Shelter featured an incredible array of musicians, including Rob Wasserman, Marc Ribot, Gregg Allman, and John Fahey. How did you get them all to participate on your first record?

That was Hal Willner's thing. He basically called in a lot of great people and basically they have very minimal connection to the music in a sense. He's incorporating performances and hoping all these parts will add up to a great whole. But in the case of that record, the songs were personal and small and he wanted to make them into a musical journey—a New York experience. Even though there are a lot of incredible people playing on that record, I don't know if that really adds up to much.

The business side of the album proved negative for you too. Tell me what went through your mind at the time.

It was horrible. It was an awful experience. Geffen didn't put any pressure on me, but they just didn't do anything. There was no video or tour support. In fact, there was no support whatsoever. I was told "The decision had been made that the record was not going to do well" and so they dumped it. It's very common. It happens to most artists. I don't know why it's not better known. Most artists who get signed to a record label believe that this is the end of a journey and that they're going to be able to express themselves, and that they're going to be able to make a living as an artist. Then you find out that record companies sign so many bands and that they're only going to work a very small percentage of those records. So, what happens to everyone else? Nothing. Meanwhile you get tied up in contracts, so you can't get out and just do your work.

The music industry is disgusting. I just think being confronted with the music business was really disillusioning for me. I didn't take it well and wanted to hide. And it was only in working outside of the music business, which is what I did on those Palominos records, that made me realize there was another way to go about it.

I saw you on the Shelter tour, opening for Joe Jackson in 1989. I recall you telling your label rep "No-one's here to see me. No-one really cares."

Yeah, I'm sure I did. I was really oversensitive then. I still am. I think I'm a lot more realistic now, though. I don't take it personally now when a record label doesn't give a shit. What they give a shit about is making money. They're not artists. We did that tour completely without tour support. We toured around in a little car. It was me, a guitarist and an accordion player.

Playing live can be the biggest high or the most crushing blow. When it works, it feels really amazing when I'm able to win a crowd over and when the sound system is good and I hit the mark with my own performance—it's fantastic. But when I feel like I'm not received well, the sound system sucks or I'm not in good voice or I screw up my guitar playing, it's equally devastating.

How have you evolved as a live performer since?

I'm definitely a lot better at it. I'm not a performer in terms of being slick. I still have a lot of inconsistencies. I'll do a show that's great and then I'll do a show that's really not up to par. But I think that's because I try not to do something that's formulaic. I try to deliver every time, but sometimes for whatever reason, it doesn't work.

Last year, Adam Duritz from Counting Crows described an incident in which you opened for the band and people were yelling at you and disrupting the gig. How do you deal with things like that?

Adam used to come out every night and introduce me and say I'm a friend of his, but there was one night when he wasn't available to do that and people started yelling at me "Take your shirt off, take your shirt off." That's what happened. When Adam got there, he went into the crowd and had the guys saying that thrown out of the concert. I've never had that experience of going out on stage and being booed. It certainly could happen. I think if somebody did that, I'd think they just weren't paying attention. I think what happens more than that is what I'm doing isn't enough to capture the attention of people who are standing there talking. That may be a very self-centered way to think about it. People come to gigs for a lot of different reasons. People sometimes just come to hang out, drink and talk, and they don't care who's playing. We're social animals. People want to congregate with others and check out each other's bodies. There are all kinds of reasons we come together. But when I play, I want it to be a shared experience between me and the audience and I try to put everything into it and hope that it catches. The good thing about having more people know about the music is there are now people who come who want to see the performance and sit there quietly and listen to everything. That's a thrill, I like that a lot.

After Pure was released, there was a buzz about a Golden Palominos tour, but it never happened. Why was it cancelled?

We tried to get it together. In 1995, we did two weeks of rehearsals. We were going to do a tour and Anton Fier was not happy with the state of it, and he called it off. Everything was booked, everything was set to go. He literally called it off two days prior to the first show. It was complicated to pull off technically and Anton wanted all the samples to be triggered in real-time through keyboards and it just wouldn't come together. We could have gone another way and used DATs, but he felt that wasn't musical. Very often, Anton's high standards prevent something ordinary from happening, but sometimes they prevent something from happening, period.

The samples where a big part of how the records sounded. For Anton, it wasn't possible to do them without the samples. But I've proven that you don't need them. I perform those songs live solo and with a band. The tour would have been amazing though because when Anton is part of something, he makes it just incredible musically—it's really on another level. Even just doing those two weeks of rehearsals, the possibility of what it could have been felt really huge.

Describe the process of moving on from the Shelter experience to working with Fier.

After I stopped working with Geffen, I probably took some time off and eventually I started playing gigs around New York again. I was playing at Tramp's and Anton was there and he came up to me and said "I have an idea for a record I want to make and I wonder if you'd listen to these tracks and see if you hear anything in them?" I didn't know it was to be a Golden Palominos album at that time. We got together and he gave me a tape of rhythm tracks—basically drum loops and bass with very little chordal stuff going on. There was some guitar, but it was pretty skeletal in terms of my understanding of what music was. This was in 1992 and it was before a lot of the loops and samples business caught on. Of course, Bill Laswell has been doing it for years, but it was new for me and I didn't know what the hell it was. It started a next phase of learning and life and music for me. It was a really incredible time for me.

How do you look back at This is How it Feels?

I love the record. I think it's the best thing I've ever done. But it seemed to be pretty invisible. We were very disappointed. When we were making it, we felt "What the hell is this? This is so important." It felt really important and then it kind of got the Restless treatment and nothing happened with that record at all. We always hoped it would have a long life in some way. It's just amazing when you're making something and you have no awareness that this is the only time that you will ever make this thing. Everything is changing as it's happening. It just existed in that moment in time and in our lives and our individual development as artists—there it is. It could never happen again. It's amazing. Anton wants to do a record of remixes of songs from This Is How It Feels, Pure and Dead Inside—the Palominos album he did after I left. Part of the reason he wants to do it is because This Is How It Feels was kind of overlooked, so he's re-approaching those pieces. But he called me up the other day and said "God, these are perfect just the way they are. I don't want to touch them."

You've said that the album marked a creative rebirth for you. Elaborate on that.

Yeah, to put it mildly. Before that point, I felt like a teenager and didn't know it. When you're 12 you think "I know everything and I'm very mature—people just don't see it." [laughs] I feel before This Is How It Feels I was 12. Everything just changed. I realized that my development had been really, really limited and suddenly there was this world of stuff I didn't know anything about and it was really exciting to me. I was at Greenpoint, Bill Laswell's studio, working every day and Bill's making these incredible records and Anton's experimenting with all this stuff on the computer and all these other live musicians. It was fucking phenomenal. It was incredible to be part of that.

Between This Is How It Feels and Pure, your relationship with Fier developed into a personal one. How did that affect the music?

I think Pure was certainly a different experience from This Is How It Feels. It was a really difficult experience. It was really, really hard. And how much of that had to do with the fact that there were aspects of our relationship that were now a personal relationship and how much was based on other factors like we were trying to top something that maybe was un-toppable or trying to do something again when really you can never do something again—I can't say. The agony that we experienced while making Pure I really do believe had everything to do with how much we both wanted to make something great and how frustrated we felt that it wasn't happening in the right way. I think we felt when we made This Is How It Feels that we came very close to making something that was incredible and that we could take something to the next level with Pure. It wasn't about replicating as much as continuing, but that was not possible because everything had changed—in terms of the innocence in approaching the material and the familiarity we had with one another.

What's your assessment of the end result?

I think Pure was unintentionally beautiful. I think it really works. I think we were trying to achieve something else and so we kind of didn't realize in fact what we had made. The aim was trying to better This Is How It Feels. At the time it felt like a disappointment, but I think there are a lot of really great moments on Pure. "Heaven" is really good song and I really like "No Skin." I think that Knox Chandler's guitar stuff is really interesting on the record. I'm also really proud of the song "Little Suicides." I think Pure is nothing to be ashamed of. I think it was a good record.

Fier has openly questioned whether or not Pure should have been made.

I certainly understand where he was coming from when he said that. I have to disagree with him. I'm very glad it was made even though it's different than it might have been and even though it was difficult to make. I think he's a perfectionist. He has really, really high standards and the record was a disappointment to him.

What were the circumstances that led to your departure from the Palominos?

After we made Pure, I just didn't want the responsibility of having to write all of the pieces because Pure was a very difficult experience. Originally, the record was going to be written by three writers: me, Nicole Blackman, and a Swedish singer named Stina Nordenstam. Stina came to New York and collaborated with Anton on some tracks. Then Stina had her record company buy the tracks and she ended up remixing them herself and releasing them on her EP called The Photographer's Wife. Meanwhile, I was trying like hell to write pieces. I was writing and writing for three months. I did a lot of work and I'd bring them into the studio and record them and Anton would say "I don't like them. Would you go home and do them again?" And one day, I came to the studio and he said "I want you to hear something I recorded with Nicole" and he played "Victim" and I listened to it and I said "You know, I'm never going to do anything like that. That's not what I do. I want to stop trying." And so, that's kind of how it happened. My stuff has a quality that's kind of lyrical. It's melodic. It's different than Dead Inside. What I do is very much represented on This Is How It Feels and Pure—that's my sensibility. Anton wanted to go somewhere else and I wasn't the right person to take him there and Nicole definitely was.

I would have liked it to have been a collaboration that had continued to be fruitful. That doesn't mean it was going to be. I gave it my best shot and it was not happening. He wanted it to be all spoken word—nothing sung. But I'm a songwriter and a singer, so that's difficult. I'm not a poet, even though my lyrics are poetic. I write in a very minimal fashion. It's not the same thing. But I tried. I wrote all kinds of stuff. I wrote stuff that was pornographic. I was trying to find the darker stuff in myself and I attempted it in all kinds of ways I could think of. I wrote all kinds of shit. But it was bad and I want what I do to be great.

You criticized Dead Inside in an interview with Raygun, in which you lamented the group's change of direction.

That article really upset me very much. The writer definitely was looking for something, but I participated. And it was right after that record had come out. Basically, my comment was not in my mind a criticism of Nicole—this is how I felt it was out of context. I felt like I was trying to be descriptive about what I do versus what she did on that record and I don't feel that was accurately represented. But since that point, I've got to know Nicole and read a lot more of her stuff and you know, it's not true anyway. Luckily, Nicole forgives me and we've gone way past that. She knows that I think she's an incredible writer and I was feeling pretty hurt after that record came out. It was kind of like having your ex-husband make this really incredible baby with his new wife. I don't know why people are surprised that it would be hurtful. Those Palominos records meant so much to me. How can it be surprising that it would be difficult to have that situation no longer exist? Basically, I was saying to this writer "I guess what I did was something that was not valuable after all because here Anton found someone who did something completely different than what I did." That's basically what I was saying. I think the passion around these situations has everything to do with how important this work was to me—to all of us. We all take it so seriously. And I think Nicole is an incredible writer and I'm inspired by her writing and I love it. It's only fair that it should be in print somewhere because that's true. And because that is true, I think Dead Inside is an incredible record.

You've worked with Bill Laswell across several of your projects. Tell me about that experience.

Bill is always so nice and sweet to me. He definitely has a vibe. I think he's very heavy. I ran into him on the street last week and I've been working on this piece he gave me for an upcoming Material album called Intonarumori. For a very long time I was intimidated by the fact that it's for Bill's record and I wanted it to be really, really great and do something different with it. When I ran into him on the street, he said very casually "How's it coming?" and I said "Well, I think I have it. I think I'm ready, but I'm a little concerned because I wrote it in a totally different key than the thing you gave me." And he said "That could be cool." I said "What if you listen to it and you think this is terrible, what was she thinking?" [laughs] He said "Why don't you just think of it as experiment?" I just loved that. He was just so cool. Bill is totally about making something interesting—his whole life is dedicated to that. That's what it's about.

I understand you get a lot of fan mail.

I do. I get some really good ones. I answer every one of them. Between email and regular mail I get about 20 a week. [Carson leafs through some letters] Here's one from a woman who talks about seeing her boyfriend in San Francisco. Her boyfriend has been in a coma for three weeks. People write about their lives and I get all these incredible letters. Here's one from a 16-year-old musician—she's so cute. She asked me for some cheesy advice, so I wrote back to her and gave her cheesy advice.

What was the cheesy advice?

"Keep doing what you love. To thine own self be true. Trust your instincts, but keep an open mind and heart." Cheesy enough for you? [laughs]

Is there a spiritual component in your work?

I think so, yeah. I'm not a religious person, but I feel very strongly about there being something and I cultivate my connection with it. I feel I do that through working and through prayer and by trying to be a compassionate person. When I think about what God is, the stand that I take is that the less I try to define God, the closer I feel to God. As soon as I try to come up with answers that are trite to me, it starts to feel not real and that's my problem with organized religion, too. My feeling is "How do you know? And how could that have happened? And why would God require these ridiculous rules?" It seems to me the more unstructured I leave it from my own thinking, the more successful I am in knowing that of course there's something. How could there not be?