Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

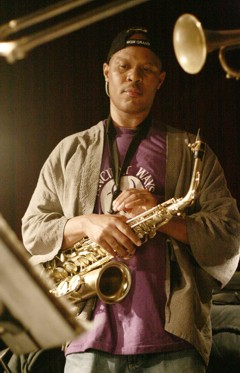

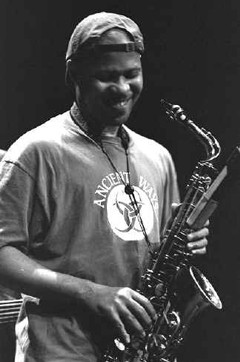

Steve Coleman

Digging Deep

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2008 Anil Prasad.

To say composer and saxophonist Steve Coleman's influence in creative and improvisational music circles is profound is an understatement. With 25 amazingly diverse albums released since 1985, Coleman has set a standard for maintaining quality and quantity throughout his prolific output.

The New York-based musician's early career included high-profile sideman gigs with the likes of Thad Jones, Sam Rivers, Cecil Taylor, David Murray, Abbey Lincoln, Dave Holland, and Michael Brecker. However, he quickly evolved past the boundaries of those associations with a very personal, distinct, and masterful approach that boldly traverses the intersections between jazz, world musics, avant-garde, hip-hop, and funk. It's also highly influenced by knowledge that extends far beyond the sonic arts.

For Coleman, physics, metaphysics, astronomy, numerology, history, the environment, and spiritual studies also play a dominant role in his musical constructs. He's studied ancient texts, modern knowledge bearers, and traveled through Africa, India, Indonesia, Cuba, and Brazil in pursuit of cultural information he can bring to bear on his output. Much of this is explored in Elements of One, an impressive documentary and performance DVD that chronicles Coleman's many philosophical underpinnings, including his core thesis that the nucleus of music is comprised of aural symbols designed to express the nature of humanity.

He's also the founder and key proponent of a movement known as M-Base. It's an acronym for Macro-Basic Array of Structured Extemporizations. As Coleman states on his website, M-Base "means expressing our experiences through music that uses improvisation and structure as two of its main ingredients. There is no limitation on the kind of structures or the type of improvisation, or the style of the music. The main goal is to creatively express our experiences as they are today and to try and build common creative musical languages in order to do this on some kind of large collective level." Several of Coleman’s key collaborators have taken those principals and run with them in their solo careers, including vocalist Cassandra Wilson; pianist Vijay Iyer; saxophonists Ravi Coltrane, Greg Osby, and Gary Thomas; and trombonist Robin Eubanks.

One cannot discuss Coleman without highlighting his impact on music technology circles either. He was one of the first musicians to launch a website that created an electronic bridge to his audience. In addition, he was one of the earliest artists in favor of online music distribution. He pushed his label BMG in that direction in the late '90s, almost a decade before the music industry woke up to its inevitable transformation. Coleman has also been a prime mover in computer-based music research. He received a prestigious commission from IRCAM, a Paris-based computer-music research center, which he used to create interactive music computer software called Rameses 2000. Coleman has challenged several musicians in his inner circle by asking them to interact with it to explore the outer reaches of human-machine artistic interchange.

Listeners long ago came to expect the unexpected from Coleman. His most recent CD Invisible Paths: First Scattering is a testament to that. It couldn't be further from the aforementioned universe. It's as organic as it gets being an album of solo saxophone improvisations.

Innerviews spent hours with Coleman discussing his unique philosophies in this expansive interview that explores his core motivations, creative process, and vision for the future of music distribution and dissemination.

What drives you to dig so deep into the origins of the music you explore?

It’s important to understand that the music is us. Take the humans off this planet and there would be no music, no talk of music, and no organized sound that anybody if they were human would call music. So, music is just a reflection of us. Delving into the origins of music means to delve into the origins of humans, of humanity, and of mankind. I’d like to avoid the word “man” but it’s in all of those words. Maybe we can just use the word “people” instead. When you explore the nature of people, you can find the nature and origins of music. The nature of all the stuff we create is within us—all these symbols, whether it’s language, money, crosses, or corporations. When someone tells you “I got this inspiration from a burning bush” or “This came to me in my head from Allah,” that’s all symbolism to me. I believe there are some mysterious, inspirational sources out there, but it’s all wired within us.

Some of this can be tracked back to the big church split in 1054 between the Eastern and Western church referred to as “The Great Schism.” It’s why we have Eastern Orthodox Christianity and the Western Roman Catholic Church with the Pope, that everyone knows. The split was over politics, as it always is, but the excuse they used was that the split was actually about the nature of Jesus Christ. Was Jesus a man or the son of God and a divine being? The Eastern Church said he was a man with special abilities, processes, and insights. The Western Church said he was God, basically, and that God was of a triune nature, meaning father, son, and the holy ghost. As for me, I believe that divine nature is in everybody and that it’s a matter of recognition, which is basically what the Eastern Church was saying.

In general, I’m a naturally curious person. As a little kid, one of the things I asked was “What is our nature? What are we?” I used to make up these “What if” things, like “What if we didn’t really exist?” and “What if our whole society and whole world was in the mind of some giant or someone’s dream and we were all only just a big part of this mental process?” Another thought I had was “Nothing exists unless I exist, and therefore none of this stuff came into existence until I came into existence. And when I leave, all of this stuff will disappear. It’s only here because it’s in my mind and it doesn’t exist outside of that.” Since I was a kid, I’ve seen movies that are more or less based on these types of storylines I dreamt up, but they came naturally to me. The bottom line is I think anything I could think of as a kid was just as valid as anything people were telling me. When I went to church, they told me “Moses did this” and “Jesus did that” and I always felt those stories were no more valid than anything I could think of, because they all came from the same place—the mind of a person or a collective. After all, we’re all wired the same way, more or less.

I know that each person is different in some ways, but when you look at a rabbit, there’s something about that rabbit that makes you not think of it as a dog, lion, or a bear. There’s something rabbit-like about the rabbit. And it doesn’t matter what word you use. We happen to use the word “rabbit,” but whatever word you use, you can identify that rabbit as a rabbit. There’s a model that we call a rabbit. If you had a pet rabbit, you may think about that rabbit in more personal terms, but for most of us, a rabbit is a rabbit. In the same way, there’s a model nature made that is a human being, and it’s wired to work in a certain way. It’s not going to act like a bird, dolphin, or an amoeba. If you study that mode, then you study everything the model creates, including these complex civilizations, stock and money markets, speech, art, and music. The model will create according to its nature, so that’s what drives me to study the history. History is just our story, but you have to remember that it’s usually someone’s opinion. You have to factor in the lies and that it’s just someone’s perspective. It’s always subjective. It’s never objective. In fact, there is no such thing as objectivity. It doesn’t exist. I don’t care what scientists say. We make the instruments of measure, we do the tests, and we judge the results. There’s nothing objective about any of this. Absolutely nothing. The word objectivity doesn’t mean anything because we cannot step outside of ourselves. No way. Never.

I understand you relate this philosophy to going beyond the rigidity of Western musical notation and concepts.

Yeah. If someone tells you there are 12 notes in an octave, and that there’s something called a perfect fourth or a perfect fifth, I say “Well, where did that come from?” People talk about certain tuning systems as being natural. Natural to us, yes, but I don’t see dolphins or monkeys using perfect fifths. [laughs] When we talk about natural, we talk about the human model. So, you have to go back to that discussion. I understand there are certain processes that happen in nature and analogies to certain processes that humans perceive, but what about the zillions of things that don’t have an analogy or aren’t perceptible like that?

I’ve found that certain numerical patterns that are present in music are also present in astronomy, sun spots, and the cycles of eclipses. So, elements of music seem to be analogous to certain natural processes. In ancient times, some people structured music to align with them. We’re still dealing with stuff from ancient times. There isn’t a lot that’s new. The structure of time, how we see time, the idea of 24 hours in a day, 12 months a year, and 30 days in a month—that stuff was set up thousands of years ago and we’re still using it, but with different instruments. Music is no different. Perfect fifths, major thirds, intervals, and scales, were set up thousands of years ago. That doesn’t mean music back then sounds the same as it does today, but the structure remains a deliberate emulation of things that happened in nature. That’s how I look at it, but the other thing to remember is, things didn’t have to go that way. There are things that seem perfectly logical to me in terms of why they emerge and I accept them. Don’t ask me what though, because it’s too much to explain. [laughs] But there are other things that I thought went left when they could have gone right. My mind naturally asks “What would have happened if they went right?” So, I follow the path that is the right path. I’m not trying to make a pun here, but I feel the correct path is sometimes the other path. And that changes my music because I make a deliberate choice to go that way, knowing full well what the other way is about. So, I study the origins of music to understand what the choices are about. Sometimes choices are about very minute things, but the result is the point. And this gets into the “why thing” I experienced as a kid. The big point is why do you go in that direction instead of the other? If there isn’t a good reason to go in that direction, then why not go in the other direction?

Time signatures are a great example of what I’m talking about. People have always told me my music is in odd time. It’s not. This is just how they perceive it. I don’t use time signatures that much, especially nowadays, unless I’m talking to someone who can only think in those terms and I have to translate something for them. Most of this stuff is coming from European structures because the dominant culture of a particular place is what imposes the rules. There’s no doubt that European or Western culture now dominates the world and the United States is an extension of that. Western culture has become the so-called norm today, just like when the Roman world imposed itself on so many places.

So today, most people think of time signatures as a norm. If something falls outside of that, they say “You’re working with odd time signatures, because I can’t count it.” I say, “That’s not in an odd time signature. It’s not in a time signature at all.” Then they’ll say “What do you mean?” And I’ll say “Time signatures are just one way of doing things.” It’s a recent method. It came from people who learned music by reading music. They talk about time signatures because they learned to read in Western notation. Remember, there are cultures right now that don’t deal with that kind of stuff. I took my trumpet player to Cuba for the first time on September 10th, 2001, just one day before the World Trade Center stuff happened. He lived in an apartment right by the World Trade Center, so he was really fortunate. One of the things I told him when we went to Cuba was “Don’t ask these guys questions about time signatures or ‘Where’s the one?’ because there may not be any one.” He said “What do you mean by that? Of course there’s a one.” I said “There’s some music where there’s no one.” And he couldn’t accept that from me. So, he asked a Cuban percussionist we were working with through a translator “Where’s the one?” The guy said “Where do you want it?” [laughs] The trumpet player said “What do you mean?” The percussionist said “One can be wherever you imagine it. So, where do you want to put it?” The trumpet player looked at me in confusion and I said “I told you not to come down here and ask cats where’s the one!” [laughs] I encountered that “no one” thing in Ghana when I went there in 1993 too. I knew that it existed and that there were other musical concepts in which you being in the right place in the music is based on different kinds of relationships. There are a lot of other ways of organizing rhythms and pitches that aren’t common in the West.

In contrast, there are things like the octave, and that’s something you find everywhere, which means it’s something that’s wired into the human organism. It’s one thing I look at that’s common to all of us. The other things are more like software—they’re changeable and can vary from place to place and culture to culture. I don’t pay a lot of attention to the changeable stuff, except where it could save my life. It’s the stuff that’s hard-wired into us that I’m most interested in because that stuff is most attached to the model of the human being and how it sees or responds to nature.

There are birds that can fly thousands of miles south and come back to the exact same tree and without compasses or maps. Clearly, they have something that’s getting them there. The same holds true for dolphins and salmon. They live among the open oceans and skies but have an amazing ability to navigate back to the same spot they started from. Something’s happening within them. It may also be the magnetism of the Earth or some sonar thing, but they can do it without signs that say “turn left here” or “500 miles to Chicago.” At one point, human beings including aboriginal and native peoples had some of that, when they were close to nature. They were able to understand it in such a way that they could read the symbols of a broken leaf or an animal trail to find water in the way that we read a sign or map today. I relate this to music in that I’m interested in making music that derives from those root sources, rather than a bunch of functions. Part of the reason I wanted to hook up with MCs is because they deal with instinct, like a lot of the blues musicians. I want to keep that component and balance it with the mental side—without getting too far into that side.

How much does it mean to you to have your listeners understand the complexities and organizational underpinnings of your work?

I learned a long time ago not to worry about what I don’t have a whole lot of control over and that’s one of those things. In traditional societies, you knew your audience because your audience was a tribe and you knew their nature. With the kind of music I do, I might play in Poland one day, Japan the next, and then America a day later. So, I often don’t know who I’m reaching. Also, people talk about America as if it’s just one culture. It certainly is not. It’s a melting pot of a lot of different cultures and there are all kinds of people here. Last night, we played to a packed house of people from different places including Europe, Japan, and Africa, who represented different persuasions, races, and cultures. So, I can’t say my audience is this or that. I may know a few people, but mostly I don’t know who’s out there and what their experiences are. So, I also don’t know what they hear and how they interpret it. In a way, “hearing” is the wrong word to use because we all hear more or less the same things, but it’s how our mind interprets what we hear that matters. We’re talking about the mind and how that mind understands things is based on who you are, how you grew up, your family situation, your education, and your culture—in essence, who you are vibrationally and in spirit.

So, I don’t know what somebody is getting when I’m playing. I played a concert in Canada and people started walking out. So I wondered “Why are people walking out?” But generally, people who don’t like your music for one reason or another don’t tell you why. They just leave before you get a chance to talk to them. Every once in awhile you get somebody who stays for a whole concert and comes up to you and says “I didn’t like your music.” It’s very rare for them to do that. When they do, I say “Well, okay. Why?” And they’ll usually say it’s because there was some expectation that you didn’t meet. It could be a lot of things. It could boil down to them having a hard day at work and wanting to take their wife out to hear some jazz, with their expectation of what jazz is. They might say “It wasn’t what I expected. You didn’t give me an evening of jazz, you gave me some bullshit.” [laughs] Every once in awhile, I get someone who knows my music from 10 years ago and that’s what they want. They’ll say things like “Black Science is my favorite album. I wore the grooves or digits out on the record and I wanna hear this guy and he’s finally coming to town.” But they may get something different and they might say “That ain’t Black Science. I don’t know what that is, but he sounded horrible.”

Of course, you also have those people who already know your music and they came because of that. Usually if they know your music, they’re satisfied. There’s a small minority of people who come because they want to be surprised. They want to go on your journey with you and see where you are now. They don’t expect you to look the same way you looked five or 15 years ago. They realize that a person moves on and they want to see what they have moved on to. A classic example would have been John Coltrane. If you had listened to Blue Trane, and then showed up to see him 1966 with Pharoah Sanders, Alice Coltrane, and Rashid Ali and they go into “The Father, Son and the Holy Ghost,” you might say “Where’s Blue Trane? Where’s the song I wore out the grooves to?” So you had a lot of people walking out on him. I talked to Rashid and McCoy Tyner about this and they recalled how people said “This ain’t ‘My Favorite Things’” and walked out. So, people have these expectations as they relate to entertainment. For ‘Trane, it wasn’t about entertainment. He almost said nothing during his concerts. He didn’t announce the band or say anything. For him, at that point, his music was something to meditate with. It was about prayer. It was on that level. But ‘Trane couldn’t change the paradigm that states “You pay your money, go into the club, drink some wine, and enjoy some jazz.” When people went to see Hank Mobley and Sonny Stitt, that’s what they got. They had an image of what jazz is supposed to be. They looked in Downbeat or Metronome and read “This guy is a top jazz artist riding high in the polls. Look, there’s John Coltrane, let’s go see him.” And then they go see him and they see a guy beating on his chest and hollering out “Om” and there’s another guy screeching on his saxophone and they think “What the hell? What happened to the finger-popping stuff I loved?” So ‘Trane couldn’t change his audience. All he could do was try to follow what it was he was trying to go after. Clearly, a lot of people have caught up now, but that’s because the man’s dead and his stuff was so frozen in time. Either you catch up or you don’t. He died in ’67—that’s 40 years ago, so there has been a lot of time to catch up.

It’s just like how people caught up with Bach. They didn’t catch up with him when he was alive, but now the whole Western musical canon is resting on his shoulders. It’s the same old story if you investigate history. You know the story. You know what’s in store for you because it’s the same human beings with the same characteristics and patterns. If you choose this path, you face the same chances of certain things happening that have happened before. Look at Malcolm X and his situation. If you look back in the past, other people faced similar problems. Check them out and see how they solved or didn’t solve their problems and that’s pretty much what’s in store for you. It’s not like the days of when we were running from Mastodons, we’re now living amongst other people and for as long as that’s been going on, the types of problems have remained. While the technology has changed, the people haven’t. The problems are coming from society. If you have a problem with the telephone company, you have a problem with people. The telephone company isn’t something that exists outside of people.

As far as the audience goes, I try to understand people. I can’t necessarily affect them in one night, but perhaps through repeated listening, a person’s general vibration can be affected by something. But in one night I don’t know what I’m going to get. I don’t have any control over the audience’s reaction.

What about your band members? How much does it matter for them to really get what you’re doing?

Once again, they’re people, but they’re not normal people. They’re obviously people that you have chosen to work with. If it’s my band, I’m usually doing the choosing. Sometimes recommendations come into play and I choose poorly. Sometimes I choose people that should work but don’t, and you find that out relatively quickly. Right now, the band I have is working fine. It’s one of the best bands I’ve ever had. Usually there are one or two people who aren’t clicking, but that’s not the case at the moment. Usually, these perfect bands don’t last long.

As far as band members understanding what’s going on, that’s up to the person. How far do they want to get into where you’re coming from and what you’re doing? That’s their decision. If you’re going to have people who are intelligent, smart, and sensitive, they are going to be going for their own things which aren’t exactly like my own things, which is great, because I don’t want them to be exactly like my things. I wouldn’t want a band with everyone being like me. That would be horrible. I might as well play solo. [laughs] The whole point of an ensemble is the end result of the music that you get from all of the personalities in the band interacting. It’s not about one person. One person may be the architect, but the end result depends on the colony of people in the band. I try to find people that are good at certain things that I lack in order to find balances. Some people are stronger on some things than others. Plus, I don’t try to play all these other instruments. There’s no way I could tell the drummer exactly how to do his job because he has been studying drums for a long time and I haven’t.

Do many of your band members take an interest in the research that informs your compositions?

They all do to different degrees, but some more than others. I had a conversation with McCoy Tyner in a Japanese restaurant once and I asked him the same question about ‘Trane. I said “Did you understand what ‘Trane was doing?” He flat out said “No.” So, I said “Well, how did you play with him?” I kind of knew the answer going into it but I wanted to hear his words because he’s an older cat and I respect him. I wanted to know where he was coming from. He was there and I wasn’t. He said “I knew ‘Trane was working with all of this number stuff in addition to all this other stuff happening. I could see him reading, but I just left him alone. I didn’t deal with that. We didn’t talk that much and we didn’t rehearse that much. That was the nature of the group. ‘Trane would bring in these sketches, give us minimal musical instruction, and then we would go off. My response to that was intuitive. I picked up on it by osmosis.” When McCoy first joined the band he didn’t play that much. He said “I laid out not to be cool but because I didn’t know what ‘Trane was playing.” [laughs] If you compare him to the pianist that was used prior to him, you’ll see a big difference. That cat tried to follow everything ‘Trane did and he got fired. When McCoy came in, he would lay out. That was smart. If you check out the records and bootlegs, as you step towards the future, he’s playing more and more with ‘Trane. By the time you get to 1964, he’s playing a lot more. Certain things had become habit like ‘Trane playing with the bass and drums, and just the drummer. That was something that developed in the band and McCoy figured it out. He figured it out in the McCoy Tyner language, not the John Coltrane language. He did things according to what he thought would work and ‘Trane wouldn’t say anything, so he would keep doing what he did. And ‘Trane’s thing was, “That’s the great McCoy Tyner. I can’t tell him how to play piano.” Same with Elvin Jones. He just let them do what they do. ‘Trane’s job was to pick the people who would do the right thing and even surprise him to get the response he wanted—naturally.

Is that your approach to choosing band members too?

It starts there. If you don’t have that, the rest doesn’t matter. I’ve had people who were the opposite and tried to understand everything but couldn’t do anything. [laughs] They understood everything mentally, but that’s not what I want. I don’t want a group of school children. I want people to have the proper response first. Sometimes you get both with a little bit of this and that. It depends on the person. It’s not so cut and dried. Each person is different, like a snowflake. As a leader, you have to be sensitive to that and understand what each person’s strength is. You ask yourself “How far can I go with this person?” I’ve had a few drummers who were fantastic—cats who could do almost anything, like Marvin “Smitty” Smith and Tyshawn Sorey. So, it’s a question of what do they want to do? It doesn’t boil down to what they can’t do because they can pretty much do whatever. They don’t have any limits in terms of what I’m going to give them. But they’re completely different people and drummers so I’m not going to get the same thing from either of them. It’s based on their personalities. I once had another fantastic drummer that could do everything, but what he did wasn’t working for me due to his choices, so the relationship ended. The other thing that didn’t work was he wanted a lot of money. I don’t make a lot of money, so I can’t pay somebody a lot of money. So when cats start demanding a whole lot, that’s when the thing’s going to end because I can’t do it. I’m not Pat Metheny or Chick Corea or one of these high profile guys.

What are some of the other challenges you face as a bandleader?

The main one is you work out your ideas in an ideal situation at home, but when you get to the band, it may not be an ideal situation. One cat may not understand what’s happening and another cat may arrive late. Being a professional, you understand these things can happen, so you calculate it into the equation. You account for stuff like “This cat ain’t gonna get it” or “This cat doesn’t want to get it.” This is also where choosing good musicians that you know can respond under the worst conditions and still come through with something that’s nice comes in. The fact is you don’t have control over anyone, including the audience. I have no control over if the drummer had an argument with his wife before he got to the gig and is in a foul mood and doesn’t wanna listen to nobody. That happens. Someone might have had a bad cigarette or cup of coffee and that’s affecting them. So, you factor in these things and understand someone in the band might be on their A game, and someone else might be on their C game. Just like in a basketball game, different people have to step forward at different times. Some people consistently step up more than others. You have to leave room for these things in the music too. I don’t plan out everything. This is improvisational music. I provide the basic structure and people do what they want within the structure. Another challenge is to enable people to do what they do yet still maintain some semblance of your concept.

You believe all music has coded information. Does that mean musicians have a responsibility to convey something beneficial when they play?

No. If you feel you have a responsibility than you have a responsibility. Obviously, most people don’t. [laughs] I think that everything has coded information whether you put it in there or not. We communicate everything with symbols, including languages. Language is nothing more than sonic symbols with agreed-upon meaning. What is Mandarin? It’s that millions of people have agreed on what certain sounds mean. The same thing with English and Latin. And the same thing is happening in music. If you’re playing creative music, you can determine what the agreements are, so it’s not just based on what’s happening culturally—although, to a large extent it is. A lot of this stuff was developed before we were born. And because you’re born into a culture—another group of agreements that have existed for quite some time—you’re born into that situation. How normal or weird you are is related to how much you choose to accept from the thing you’re born into. If you’re a so-called normal American, you pretty much accept a lot of the standard things everyone talks about, such as the “American way” and all that apple pie shit. [laughs] That puts you right up in the middle. If you move a little to the left or right, figuratively speaking, not politically speaking, these codes still affect you.

Music has historically been used as a language, as well as entertainment. When I look at the historical development, the code thing was always there. It’s something that’s very strong in the past, but what’s happening in our modern entertainment culture—especially in America—where you have a McDonalds “satisfy me now” thing, it’s not so apparent. Or they use the codes for different things. For instance, when you walk into a supermarket and they use music to try to get you to buy stuff or when you go to a scary movie and the music is designed to scare you. Both are examples of music used for a purpose to get you to buy products or as a psychological tool. The goal is to tweak something here, something there, and get you to act in a certain way. In contrast, people like Coltrane and Beethoven were working in a more metaphysical realm. What I’ve found by going back and studying history is that there is a purpose to the structure of music. It wasn’t just random activity that resulted in how these structures developed. During this process, I asked myself “What’s different in all the musics of the world?” That’s an obvious thing to look at. So, I chose to look at what was the same in all the musics of the world. It helped me to identify something in the human patterns I talked about earlier.

What are the commonalities or unities that you’ve discovered?

It’s hard to talk about, but there’s a certain way of dealing with time, pitch, octaves, and the structure of music in every culture. It’s something you only really see humans doing. When lions roar, it doesn’t sound like music. They don’t vocalize in unison or in octaves. Wolves have their thing happening, but it’s not what you’d call music either. There are some creatures whose language is reminiscent of music, like that of birds, but when you study bird calls, you’ll find they are quite different from what we call music. It’s a very different structure because part of what human beings do is quantize. If you look at everything we create and how we understand things, quantizing is a part of it. Now, I’m not saying that our initial intuitive impulse is coming from there. I think it’s coming from a place that’s different from that. However, the augmentation and understanding process is definitely coming from the quantizing standpoint. We take that and apply it to everything. It’s our way of organizing things in our brain because the way we understand something is that we code an image in our head. We don’t necessarily understand it in words. You can think a thought and there don’t have to be any words involved. You can think of an entire concept in a flash, but when someone asks you to explain it, the words may take a long time to come. Einstein understood relativity in a flash, but it took years to work out and develop in the language of mathematics in a way that other people could understand. I’ve experienced this myself. I’ll get an idea for an entire concept in a flash just upon waking up, but working that out, or explaining it in a way for others to understand can take awhile—sometimes it takes years.

What influence does spirituality have in this discussion?

Inspiration deals with spirit. In fact, the word “spirit” is within the word “inspiration.” In ancient times, spirit and breath were considered the same word. That’s because the breath of life and the spirit of life were the same thing. They didn’t necessarily mean breath as in breathing in and breathing out. Rather, it was related because both air and spirit were things you couldn’t see. This thing of air moving in and out of your body is what all living creatures had, so it was felt that this related to the spirit. Again, that’s why the word “respiration” has “spirit” in it. So, breathing happens, even if you can’t think, and even if you are in a coma. Breathing remains and it’s mysterious and something that scientists don’t understand. You can ask them what life is and they can talk about the processes and elements of life, but they can’t tell you what life is itself. Further, cloning is not life because you’re starting with something nature has given you. You’re not creating the thing itself. No-one actually know what’s inside the sperm that’s transferred to the egg. However, this isn’t part of augmentation. Augmentation is what develops in our species and other animals have it to different degrees. So, while it’s hard to explain the source of the idea, you can say its outcome is contingent on other things you know from the past, so a layering process is at work. If you were brought up by wolves, you’re not going to have an idea about some musical system or relativity. You could have been the future Albert Einstein, but you won’t get the relativity idea because you didn’t study and didn’t have the background to lead you there. So, I personally believe that ideas are independent of what you know, but if you had been brought up by gorillas, that idea would have to do with gorilla stuff.

For me, spirituality is simple. If you’re alive, it’s there, whether you want to recognize it or not. It’s not that mysterious. It’s just a matter of internal searching. If you deal with dogma, maybe you can accept something wholesale that someone gives you. It’s a case of “Here’s a platter. This is your meal and you have to eat it without any adjustment.” That’s the religious stuff and it’s for people who simply do exactly what they are told to do. I’m not one of those people. I’m a questioning person and the questioning comes from inside. So, ultimately, I know that if there is any kind of spirit—and I believe there is—it’s inside of you. I study and check out what other people are thinking because they have the same thing inside of them, so I’m curious to know what they came up with, but the ultimate answer is always going to come from within.

Can you describe how you go from inspiration to a finished composition?

I always try to think in a way that makes intuition and logic work together so they become one thing, so I don’t place an importance on one or the other. It’s like a ping-pong game. I let them both go at it and they bounce the ball back to each other’s side at light speed. Both things are happening at the same time, so it’s hard to see which side is getting the upper hand. I also use dreams and accidents—anything that I can possibly mine to create any and all things. The other thing I do is use correlative thought in which I see the similarities in things. For me, that’s a big thing. Some examples are the similarities between boxing and music or sex and music. All of it is coming from the same source. So, being able to see the similarities and correlate them helps from an inspiration standpoint, and also from a logic standpoint.

When I was younger, I had a conversation with a friend of mine while we were looking at a mountain. I said “Man, it would be great if I could play that mountain.” He said “What do you mean by that?” I said “I want to pick up my horn and play the mountain.” He said “You mean, pick up your horn, be inspired by the mountain, and play the feeling?” I said “No, not play the feeling, but actually play the mountain.” He said “That’s impossible.” I responded “If I put a piece of music in front of you, you can play it, right? So, what I want to do is look at the mountain and have it represent something to me in symbolic form, just like the notes on the paper do and just play it.” Again, he said “That’s impossible.” I said “It can’t be impossible. It must have been done before. Other people must have thought of it if I’ve thought of it.” So, that’s one of my goals—to look at nature like cloud patterns or bird formations and be able to play them. I discovered from studying that other people did in fact have those same ideas and tried to express that in various ways. My job as a musician is to study musicians who’ve done that, just like architects study the work of other architects. I try to understand what they did and figure out what parts are applicable to my standpoint and sensibility, and how I can use them. Some stuff I agree with, some stuff I don’t, but the point is to study.

How have you evolved as a saxophone player over the course of your career?

In some ways, I might have become worse, technically-speaking. I had a conversation with Sonny Rollins and he told me how people always come up to him asking how come he doesn’t play this and that, and why he doesn’t play a certain way anymore. They’re talking about records he made when he was 25 years old. He said “Man, these people don’t understand you’re not the same person. It’s like asking someone who’s 60 years old why they don’t run the same way they did when they were 25.” Some of it is physical, but a lot of it is he doesn’t have the same concerns he had back then when he was younger and wanted to play really fast. Rollins said you develop a certain amount of patience as you get older and I agree.

Younger people have been alive a shorter percentage of their lifetime. If you’re three years old and someone asks you to wait one year before you can get a toy, you’re looking at waiting for one fourth of your lifetime, so that feels like a long time. But for a person who’s 60, one year is a much smaller percentage and they can say “It’s just a year. I can wait. No problem.” So, time flies, as they say. It moves at a different pace as you get older. What that means for me as a player is that I’m concerned about different things. Like with Rollins, when I was younger, I wanted to play everything at breakneck tempos. Everything was about “fast, fast, fast.” Even sex was fast—you know, bunny rabbit sex. [laughs] Now, I like slow sex.

When I was really young, around 18 or so, and got into the music, I only liked the cats that could play fast. I didn’t like slow players. I remember once going to hear Dexter Gordon when he came back to America and I was thinking “This cat plays sloooow.” After awhile, I got into it, but it took me a second because I was into fast stuff back then. I was practicing playing fast too. I remember reaching a point where I was practicing technique just for the sake of technique and realized that it was stupid. I thought to myself “Now, I can play faster than fast, but what’s the point? I just need to know how to play. Not fast. Just play.” So, I concentrate on technique now to a certain extent, but not like when I was younger. Now, when I hear a young cat just playing fast, it rubs me the wrong way. They’re playing a lot of nothing fast.

Because my philosophy has changed, so has my playing. The technique in improvisational music is based on what you’re trying to say. I say that because improvisational music is different than music you play with an orchestra. If you’re with an orchestra, your technique must be based on the repertoire you’re doing, otherwise you won’t be able to play it. With improvisational music, a lot of what you’re saying is coming from an interior source. You’re a spontaneous composer and your technique is related to what you’re trying to say. For instance, Coltrane’s technique was based on what he was trying to say, rather than on Johnny Griffin’s or Sonny Stitt’s technique. It’s somewhat similar because they were all within a general language and culture area, but it’s very different if you really look at what he did from a saxophone standpoint. In my early days, I could play faster than I can do now, but I can also do things now that I couldn’t do back then because I had no reason to do them at that period. A couple of examples include microtuning and alternate fingerings that I use. Now, it’s all motivated by what I’m trying to express.

You explored hip-hop in a pretty serious way with your group Metrics. What inspired you to merge hip-hop with live instrumentation and improvisation?

Hip-hop had nothing to do with it at all. I don’t view music in terms of styles, words, and categories. Most of what people call hip-hop I don’t like at all. So, it wasn’t hip-hop that I was going after. The perspective I’m coming from is that in the black community—and this is really general—there are two streams of music: the more sophisticated forms and the more unsophisticated forms. You also have this in people in that there are those who are more sophisticated or less sophisticated. That is not to say sophisticated is necessarily better than unsophisticated, but you usually gravitate towards one or the other. I tend to gravitate towards the sophisticated thing. But knowing that, I feel like I need to reach out and relate, and grab an element of the other that I don’t gravitate towards for the sake of balance.

Another way of putting it is that I can recognize that Charlie Parker’s music is sophisticated, and yet I can also recognize that it has elements of the blues which, generally speaking, is not sophisticated. I’ll get arguments from Wynton Marsalis and others, but my point of view is that blues is music that you can call folk music, for lack of a better word. And my definition of folk music is that it’s music from folks—regular people. It’s music from people who are more concerned with the original impulse of the music than they are with the mental development of the music, which is what I call sophistication. This is not to say the music is simple, because you can have tribal music that is anything but simple. What Westerners fail to see is that that there are different levels of sophistication in tribal music. What some child on the edge of the circle may be doing may not be sophisticated, but what the master drummer is doing may be very sophisticated. So, people participate in the music at the levels at which they are capable of participating. Tribal music is structured so that both the sophisticated and unsophisticated can participate simultaneously. Generally speaking, that is not true in Western culture, where sophisticated music needs to be done by people with sophisticated skills. Anyone can’t just sit in on a Wagner orchestra that hasn’t practiced. And anyone couldn’t have sat in with the John Coltrane quartet, although he deliberately brought unsophisticated elements into his music to balance things out—and that’s where I learned that from.

So, I’m not looking at this as hip-hop, but rather the impulse that develops hip-hop. Hip-hop is the blues of today as far as I’m concerned. I don’t mean it’s like the blues, but it’s coming from the same impulse when it’s not so commercialized. It’s hard to find someone these days coming from that impulse that isn’t trying to make a zillion dollars and become Jay-Z. That’s the hard thing. My challenge was to find musicians coming from that area who weren’t sophisticated or trained, and still had the impulse. I wanted people who were mainly doing something from a feeling aspect, but were still interested in creativity and not locked into that “I want to be the next Jay-Z” idea. It took me years to find them. I had been trying to do that for a long time—much longer before anyone heard it on record. I had friends in New York who knew what I was trying to do that said “You’re never going to find anyone who can deal with the stuff even close to what you’re dealing with within that sensibility because all them cats are rockheads.” I heard it over and over. I eventually found some people that are part of a group called Opus Akoban and I still work with them.

These people changed over time after I hooked up with them. They’re not the same cats. They’re more sophisticated. They’ve been influenced by us and vice-versa. That’s what always happens. If you go to Brazil with my group, you’ll see that I leave some cats there that are influenced by my stuff and they change. I went to Cuba for a long period and there is a whole group of Cuban cats, some of whom left, and some of whom are still there, that are influenced by offshoots of offshoots of offshoots of what we did there. It’s funny. I didn’t realize it until I heard a lecture by Chucho Valdez, who is a lot older than me. He said “At one point, Steve Coleman came to Cuba and now there’s this whole Steve Coleman trend.” And I was like “What?” But then I thought about it and realized it’s true, especially in a place like Cuba where there’s very little information. What you do may have a bigger effect than in a place with an overflow of information.

Can you point to some hip-hop acts that you dig?

There are very few. Back in the day, I liked what Public Enemy was doing as far as a popular act. In terms of a not so popular act, I liked Poor Righteous Teachers. I liked their rhythms, but they had a “Five Percent Nation” street Islam thing that I thought was bullshit to a large extent, but I still dug their general thing. I liked Public Enemy a lot better in terms of their whole thing, especially what Chuck D was dealing with. I also enjoyed the musical part of Public Enemy in terms of the sonics they used. I even met with some cats in the group a couple of times.

I liked Wu Tang Clan too, though it’s hard to say what it was I liked about them. I liked the comic book and kung-fu stuff when I was young. My whole interest in Eastern philosophy came out of an adolescent entertainment thing like Bruce Lee and samurai movies. As I got older, I got into what was behind the entertainment. I checked out some Confucius writings and it led me to something real, even though in my youth it was pure entertainment. With Wu Tang, I wondered if the same thing would happen with them. Would they get past it and get into what was real? That’s what happened to me. Even my group’s name Five Elements came from my early interest in martial arts and boxing, and my interest back then wasn’t philosophical. Public Enemy was much more mature than Wu Tang. Most of the groups now deal with cursing and the denigration of someone. I’m not into that because usually the subject matter and the music match each other.

Since leaving the BMG label, you’ve practically become an underground artist in the U.S. in that your music is only available as imports these days.

Not practically. [laughs] I don’t have to explain what’s happening with the record industry to you. These days, those who were a little above ground before have gone a little bit underground, and those who were underground have gone further underground. What can I say? It’s nothing new. I’ve been living in this area for a long, long time. I started off underground and I was never much above ground, so being underground is a normal state. I don’t know how widely heard my music was back in the BMG days. I’m going by how much I was working in the States. Today, I work in the States about as much as I always have. There are up and down years, but there’s never been a killing year. On the other hand, when I go places, I find people who know about the music and I get asked all the time “How come you never come out to Australia?” That’s a place I’ve never been. I get these from all over the place because people are really good at getting on the Internet and searching for stuff. And when people get excited about something, they turn into preachers and disciples and spread the word to their friends—especially young people who take pride in being hip to something that others aren’t hip to. Gary Trudeau, who does the Doonesbury comic strip, once included a blurb about M-Base in his thing. One character was asking another character about it. We chuckled because it was mentioned. So, Trudeau must be aware of it to write about it, so he’s pretty hip in terms of knowing things, but the truth is, it was an underground thing even when it was being talked about.

Your website is pretty low-tech, yet it’s one of the most useful out there. Describe the philosophy behind it.

That website has been there since what most people would consider the beginning of the web. I was into computers in 1985 and was doing email back when it was still referred to as “electronic mail.” I remember the first demonstration of the web at UC Berkeley. I said “This is going to change the world.” The other guy with me said “I don’t see how this is going to change the world. It’s crashing every two seconds! Nothing works.” I said “But can you imagine what will happen when this spreads?” The other guy didn’t see it.

When I got on the Internet, there was no commercial presence. It was just a bunch of geeks. Then the guy who demonstrated it for me said “I can build your web page for you.” I said “What do you want?” He said “Nothing.” That set off a big alarm in my head. I was like “You want to build my web page for nothing?” Something wasn’t right with that. I thought “There’s something I don’t know and I need to find out what’s happening here. Nobody in this country, especially if they don’t know you, wants to come up to you and do something for nothing.” So, I researched it and realized everything was basically free back then, including the browsers. People were just trying to get real estate because they realized this thing was going to be big and wanted to build a presence. This guy wanted to use my name to build a presence for his own website. After I figured that out, I turned him down and said I can do this myself. I went out and bought a book on HTML because at the time there were no HTML editors. You had to do all this stuff in a word processor. I learned how to do it and I didn’t have to put it in any search engines because the site was there before the search engines were. [laughs] It was always there. If you Google it, it comes up right away. I’ve resisted changing it too much because I like the old school look, but I wanted to put up more information and add things to it, so it’s evolving. When you come to my website, you won’t see bouncing dogs or clowns or stuff opening up in Flash, but you will get real information. On other sites, you get all the bells and whistles, but when you dig in, there’s nothing there.

You give away complete albums for free from your back catalog on your website. What drove you to do that?

What happened with me is I chose to go on an 18-month sabbatical around 2000. I wouldn’t say I was reborn, but when I came out of it, I had some different ideas. I took a break from performing and recording, but not music. That alone shocked BMG, my label at the time, but when I returned, my ideas shocked them even more. I went to BMG with the idea of making a record and giving it away for free. It took me a long time to convince the guys in the so-called jazz department that the paradigm is changing. I told them we have to get with a new program because things are going to be different and you can’t copy-protect everything. You can’t beat these people, so it’s better to join them. Buying music has always been a young person’s game. Old people, relatively speaking, buy very little music. So, if you want to get with what’s happening today, you have to get with this young crowd who are buying video games. So, eventually I convinced the BMG guys I worked with and they took those ideas to their superiors who said “You’re crazy. Get rid of this guy.” So, that ended my 10-year relationship with BMG after being with them from 1990 to 2000.

Around that time, I was going to do a concert in the south of France, record it myself, and give it away. That was my plan. The head of the jazz department at BMG liked me and what I was doing and thought it was very important. He had a fantasy in that the reason he brought me to his department is because he thought he was like Coltrane’s producer on the Impulse! label. He liked the idea of sneaking Coltrane into the studio in the middle of the night, even when the bigwigs were like “Don’t record this guy no more. He’s killing us.” So, he was that kind of guy going against his superiors and hiring this renegade person. He told me later on he thought I was his Coltrane. I said “I ain’t Coltrane. You’re tripping.” And so he was sad that this relationship was ending and wanted the story to go on. So, he contacted this other guy at Label Bleu, a smaller French label which wasn’t as beholden to a big organization. He said “Steve Coleman is about to go out on his own and you should grab him before he does that, but know he’s got some pretty weird ideas.” So, the guy from Label Bleu contacted me.

We were on tour, and the cat contacted me on my cell phone on the train and said “Can I meet to talk with you before you do what you’re trying to do?” I said “How are you going to meet with me? We’re touring and moving around.” He jumped on a train at one spot and our meeting was between that spot and where we were going. It was like an Orient Express type of thing. So, we had a meeting on the train car and by the time we got off the train, we had a deal. He listened to all my stuff and I told him how I was going to give away stuff on my website, make this free record, and how the record industry was changing, and he said “We’re with you. We can make it work. Come with us and we’ll work with you.” I was like “Really?” [laughs] I was in shock. That’s been my relationship. I know they didn’t have good distribution in the States, but what I was more interested in was that they were going to support these ideas. We worked out a really great deal that worked for me. It wasn’t great financially, because the budgets were smaller. Now, Label Bleu is going through the blues like every other label is. We have one official record in the can with them, but they’re having problems with distributors, so its status is uncertain.

Looking back, I had a lot of problems with BMG. Even though I put out records with them, I was fighting all the way. The whole reason I went with BMG France was that I wanted to do a record in Cuba and the BMG label in the U.S. said “No. We can’t do anything in Cuba. We can’t support that.” So, I had to go outside the U.S. to deal with that just because of stupid politics that I have nothing to do with. There was also always somebody at BMG in America trying to get me to make a record with TLC or Destiny’s Child or something like that. It was constantly happening. The R&B division would come up to me and say “We feel like you have some kind of sensibility and it would be great if you would do a record with such and such.” I said “Great for you. Not for me.” I was moving in an esoteric direction and it didn’t make much sense to them. The straw that broke the camel’s back was when I did the Genesis record. They probably heard it and said “What the hell?” It’s a large group thing with all this Kabbalistic stuff, and it wasn’t quite Coltrane’s Ascension, but it may have sounded like it to them.

Ascension to Light, your last BMG record, didn’t come out in the U.S. at all. I guess the writing was on the wall at that point.

That didn’t come out here because it was caught on the tail end of the relationship. It was a casualty of the executive wars, so it didn’t make it. It was released when all this stuff I told you about went down. So they gave it a minimal release and went through the motions. They didn’t really release it. They just sat it on the side.

I understand you’ve decided to record independently of any label, documenting music as it emerges without an immediate concern for how it gets distributed.

I’ve gone back to the way people used to do things in the Charlie Parker days in which they would keep going to the studio and some stuff made it on records and some stuff didn’t. Most of the records you hear back in those days were not made as complete albums. They would go in and do four or five songs and that would be it. Then they would go in and do some more. Most of the records you bought were compilations of those different things they did. A lot of Coltrane records are like that too. So, I’m doing that now. I don’t wait for a record company because the way they work is to create a schedule and every year or so say “It’s time to make a record.” I’ve always hated that. I decided if I have enough resources, I’m going to make a recording when we have something to say, and by the time an album opportunity comes along, we’ll have plenty of stuff for it. I look at records as a snapshot documentation of what’s happening at the moment. There’s none of that kind of “I made this record because my father died” stuff. Let’s face it, people think about that stuff after they made the record and then try to figure out a line for it. That’s where you get a guy like Sting saying “My grandmother passed and I was going through a hard period, so this is my thing to do.” Meanwhile, in the studio, they’re thinking “What hook can we put on this to sell records?” [laughs] So my thing is, when we have something to say, we’ll go in and document the stuff. I’m documenting a lot of my live stuff now. Recording equipment is good enough now that you can actually put out what you record live. However, you don’t want to flood the market with a whole bunch of stuff that nobody can digest.

With Weaving Symbolics, I was already at the stage of doing this. A lot of those things were recorded in different places—mostly in Brazil, but some of it in the U.S. too. That’s part of the title—weaving and putting it together. If nothing else, I’ll put out the music myself. I’m not worried about it because I didn’t get into this business to make records. Records are an offshoot of technology. If I lived in Beethoven’s time, there would be no records. For me, the main thing is just playing—and I don’t necessarily mean even in front of people, because most of what musicians do never gets heard, except by the musicians themselves. There’s a lot of playing that goes on in people’s houses and that’s how it started for me. It didn’t start off on a stage in front of people. It began from just wanting to make music and getting together with some guys and doing that.

Going back to the underground thing, yeah, I’m underground—certainly from the standpoint of Wynton Marsalis, but I’m way more above ground than when I started. [laughs] So, that’s how I look at it. I’m very fortunate in that I’m doing what I want to do in life and that I can survive through it. I’m way more above ground than when I was living in Chicago or when I first got to New York and was playing on the street for a living. So, I think I have come a long way and I’m doing what I want to do. Some musicians aren’t doing what they want to do. They’re doing what they have to do to maintain their status. You know what happens to rich people—they want to keep what they got. I had a long talk with Cassandra Wilson about this. A lot of professional musicians really are working for other people who are like parasites, making money off what you’re doing. I never want to get into that. I only want to do what I want to do and if history is any teacher, that means you’ll be underground. Once you become popular, it’s not just about you. It’s about all these other people who have this interest in everything you do. No matter how you got to your point of popularity, they’re only interested in keeping you there instead of letting you take another road other than the one you took getting there.

In your liner notes for Weaving Symbolics, you wrote “I hope the music can help carry you inside yourself.” Can you expand on that?

I look at this music the same way I look at acupuncture. The point of acupuncture is not that it heals you, but that it releases blockages, which enables the organism to heal itself. Coltrane was once asked “Do you believe music can change people?” He said “I wouldn’t put it that way. I believe music can influence the initial thought patterns that can go on to change a person.” That’s very similar to acupuncture. Change comes from within. I think it’s typically not that easy to go inside yourself because you have all these external things constantly involved in taking you outside of yourself. The material world is outside yourself. So, for most people, their entire world is outside of themselves. Most people don’t even mention anything interior except for little clichés like “I feel this” and “I feel that.” Normally, they’re not in touch with what’s inside them. So, that’s what I was talking about. Sonny Rollins once told me “I think there are two kinds of music: that which expands and that which contracts. I want to be part of the tradition that expands.” He didn’t mention categories or anything. He said “For instance, when you turn on the television, everything you hear, musically-speaking, contracts.” By that, he meant contracts consciousness. So, he wants to be involved in music that expands consciousness. He put it into eloquent words. That’s the trend I want to be part of too. It has nothing to do with whether it’s jazz or some other category. There are some people that have tried to create music that puts you more in touch with what you are, not who you are, but your internal essence. That’s what I want to do.

Photo Credits:

Photos 2-5 and 7 by Juan Carlos Hernandez

Photo 8 by Michael Wilderman

Photo 9 by Luciano Rossetti