Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

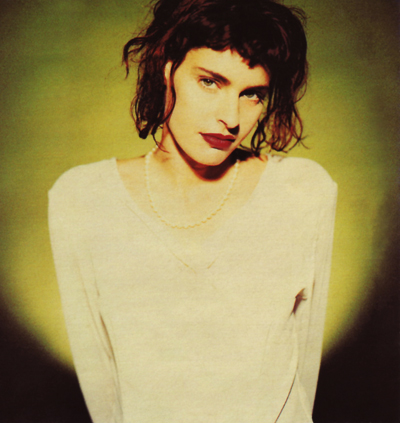

Deborah Conway

Crucial Timing

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1997 Anil Prasad.

During Deborah Conway's Australian tour last October, the singer-songwriter was joyfully performing six-months pregnant in a red-sequined dress with a rhinestone-highlighted heart cut-out over her baby bump. To say the result was an eye-popping concert experience is an understatement.

Making a spectacle of herself is nothing new for the occasionally controversial native of Melbourne, Australia. After all, this is the woman who posed nude, covered in Nutella for an album cover. She also had an Australian hit single with the band Do Re Mi titled "Man Overboard"—a song about penis envy that created a public uproar.

Conway’s mercurial attitude is something found throughout 1991's String of Pearls and 1994's Bitch Epic, her first two solo albums of adventurous and dynamic pop. Her latest effort, 1997's My Third Husband, is another step forward in her evolution. Unlike its predecessors, it's fueled less by pop melodies and more by richly-textured, forward-looking atmospheres. The disc takes listeners on an unpredictable aural journey through tranquil and turbulent soundscapes. It derives its diversity from a mix of hypnotic rhythms, ambient synthwork and processed guitars—most of which are courtesy of her multi-instrumentalist partner Willy Zygier.

If there's one constant throughout Conway's work, it's her elastic voice—one that effortlessly shifts gears from serenity to tear-your-head-off intensity. The same can be said for her lyrics which explore scars of pleasure and pain, the complexity of self-realization and the blurry line between the sensual and the sexual.

Innerviews caught up with her just a few weeks prior to the birth of her daughter Alma DelRay Zygier.

You and Willy worked primarily as a duo in your home studio when putting together the new disc. What were the challenges you faced?

There were many surmountable challenges, the main ones being learning how to use all the equipment we had just acquired and juggling that with looking after a new baby. We spent a large part of our time in the studio with our heads in manuals—dull at the best of times, but particularly hard when you're fighting ‘breast-feed brain.’ Other problems stemmed from trying to do what we were doing in a flat with neighbors top and side. No-one likes listening to cranked-up guitar feedback at ungodly hours, so timing was crucial and amp placement was a scientific exercise. Being a duo seems to be a standard way to make music these days anyhow and didn't in itself pose any problems except for the obvious difficulty of both of us juggling working and parenting. As far as feeling the lack of other inputs or musicians, I think the isolation worked in our favor. We relied more heavily on the sampler which dictated how the work sounded in the end—the ideas were purer in a way without compromises.

What did you learn about the recording process?

That in many ways it's more difficult but also easier than I had thought it would be. As a totally unschooled engineer, I was unafraid to do things to the sound that would make a professional balk. We had fun with it—pans, effects, fuzz, distortion, as long as they sounded good. What I learned later was that what sounded good in one environment didn't necessarily translate to another.

What did you learn about yourselves?

Hard question. I suppose there was a feeling at the end of the process that we'd been vindicated in a way. The project had undergone such opposition from different quarters and by the time we'd closed the door on the last day of mixing, I felt like we'd undergone an enormous test and passed it. I guess I felt pleasantly surprised we had been capable of sticking to our guns in the face of all that adverse criticism.

Who was responsible for the opposition and what was their reasoning?

I shan't mention who as it's irrelevant. Reasoning obviously came down to what people valued as commercially viable and our material was not viewed as such.

What were some of the musical influences you drew from when creating the arrangements?

We talked about the direction for the record at the beginning of the writing process and had come up with the ambitious notion that we would attempt to write classic songs for the fin de siecle. I'm not talking about songs that sounded like you'd heard them before—they would be original but classic in a Cole Porter, Irving Berlin way. So, it might be possible that anyone could take one of our songs and do their own interpretation of it. I didn't want to write songs that were insights into Deborah Conway's life, I wanted them to have a wider application. At the same time, a lyric must have a basis of truth to ring true with a listener—taking the personal core and applying it to a universal truth. I think that is also reflected in the way I chose to sing the songs. Influences included those classic show tune songwriters, as well as what we'd been listening to over the last few months—Bjork, The Passengers, Radiohead, Beck, Liz Phair, Portishead, Spain, Faithless, Howie B. and others all worked their way into our psyche, plus old favorites like Nino Rota, Bernard Herrman, Sinatra, John Zorn, Michael Nyman and the Beatles were all there jockeying for position too.

Describe the origin of the line "I am on my own with no-one to defend me from myself" from "All of the Above."

It's about the self-destructive nature of creativity. In reference to songwriting you so often—or I do anyway—have to die a little before giving birth to a new idea, lyric, melody, whatever. Due to the intense schedule we'd been sticking to, I felt like I was dying more than giving birth. And the dying was at my own hand.

A couple of songs from the new disc are re-recorded versions of tracks that appeared on the Ultrasound project in 1995. Describe how it came about.

Speaking of giving birth... I went for the standard 18-week ultrasound when I was pregnant with Syd. We came out of the room gobsmacked by the technology of it all and couldn't stop talking about it. Willy said half-joking we should call a band Ultrasound. I got very excited about that name. I think in fact that if it hadn't been for the name, the project, unlike the rose, would not have existed. After that, it was simply a case of asking Bill McDonald, a long time associate and easily my favorite bass player, and Paul Hester, an old friend and superbly anarchic drummer, if they wanted to be involved. Willy had some old Tootieville [his old band] songs lying about, I wrote some new ones with Bill and Willy, and we dug out Bacharach's "Anyone Who Had A Heart"—before it was fashionable. We recorded the whole album in five days at Tim Finn's home studio in Melbourne and mixed in another five days at a more swanky establishment that blew the budget out to a total of $10,000. It was cheap at twice the price. I spent a lot of time lying about on couches like a beached whale in heat wave conditions with only a few weeks to go before full-term. I still think the singing on that record is the most relaxed I've ever sounded.

Did the Ultrasound experience plant the seeds for what would become the new album?

We definitely learned a lot from the experience. Firstly, it was the early forays into using computer-based technology to create the sound and secondly, that we'd been able to pull the project together so cheaply gave us a lot of incentive to do it again in a home recording environment.

Did anyone pay attention to the Ultrasound disc in Australia or did it get lost in the shuffle?

Different radio stations played "3 Love" and "Only the Bones" and the reviews were very positive but ultimately it never really got off the ground. Perhaps our approach was too low key. I'd been very adamant that the promotion should match the project and consequently it was a very understated affair. I was out of action anyway having just had Syd, so there were no videos or ads and only a couple of interviews with Paul and Willy. For whatever reason, it didn't seem to capture the Australian heartland.

The new disc possesses some ambient and trip-hop influences which are very much in fashion at the moment. Why has marketing this record been such a challenge for your label?

Perhaps it's because once you've been pigeon-holed and filed away under a particular label, it's very difficult for record company and media alike to allow you to elude them by making a very different record. They'd almost rather ignore it than have to call up your file and rethink your category. That’s just a guess. The other major source of frustration for them was not being able to secure radio play. In the two-and-a-half years since Ultrasound was played, radio has become increasingly and frighteningly conservative in this country. We found ourselves too soft for one station, not rock enough or too hard for another, or they only play Celine Dion and Mariah Carey, or we’re too alternative for the alternative station. This has recently been remedied on the last of those mentioned with a high rotation add for "2001 Ultrasound." The record company is relieved.

Describe your relationship with your record label.

Honest to a point, cooperative, at times intimate and comfortable, at other times frustrating. Like all organizations made up of individuals, it varies on whom I'm dealing with, but mostly we understand each other even if they think I'm difficult. It's been long enough to be affectionate, but never long enough to let affection get in the way of making a profit.

What difficulties do you face working within the Australian music industry?

I'm not sure I can answer that question having never successfully operated outside it. But I have always found a terrible shortage of good management here and for a long time I have undertaken that job myself and I don't like it.

CDs in Australia are incredibly expensive. Do you think that forces many to stick with the tried-and-true, rather than taking a chance on something different?

CDs are priced here between $20 and $30 dollars, still more expensive than the U.S., but then everything in this country is. There is a debate going on at the moment about this issue. For a long time, an organization set-up as an advisory board to monitor pricing practices has been advocating the dropping of the ‘Parallel Import Provisions’ in the copyright act. This would effectively undermine anyone with a record released overseas and not doing as well in that country as it was doing in Australia. Ultimately, it would lead to a decline in the local business with more money going offshore and less being invested at home. It's a contentious issue with the multinationals and the tiniest independents all finding themselves on the same side of the fence. Disturbing. The other argument is that government should drop the hefty sales tax it has on CDs, though naturally that's unlikely. Whether the prices stop people taking a risk with new music is the argument the government has used to advance their case—in other words, if CDs were cheaper more would be sold. Who knows? The question facing us is whether Australia should undermine the rights of its songwriters and possibly bring about the shrinking of the local business in order to find out if it really will bring down the price of CDs and if people will take more chances on music they don't know.

How did you balance being new parents and creating the album?

We wrote at night when hopefully she was asleep with two major consequences—we got less sleep and we wrote a night-time record.

In general, how has becoming parents changed your worldview and priorities?

It hasn't. Well, maybe I prioritize sleep more.

How and when did you and Willy first meet?

Willy was recommended to me as a guitarist by our mutual friend Richard PIeasance. I employed him for the String of Pearls tour at the end of 1991. He came 'round to meet me at my flat after we'd spoken on the phone a number of times.

When did the relationship transcend the musical? And did it affect the music?

I recognized almost immediately a kindred spirit and a cute arse. I've always found that publisher's wet dream of putting two or more songwriters in a room and seeing how many hits they can write a very foreign one for me. I like to know people and have developed a trust in how they react in certain circumstances before I can let my guard down in one of the most intimate human exchanges there are. Consequently, all the people I've ever written a song with are friends.

What are some of the reactions you're getting from the audience and press at performing in a very pregnant state?

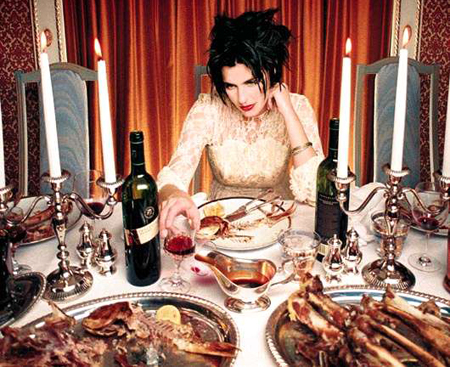

I've officially got about six weeks to go, but my gut tells me it's probably more like four. The first leg of the tour was with a full band and a six-month belly. I frocked up in red sequins with a large heart cut-out over the lump in gold mesh and highlighted with rhinestones. It was a showstopper with a slow reveal as the guitar which I played for the first 5 songs covered the heart completely. I wanted to get Shirley-Bassey-meets-Danny-La-Rue in a postmodern pastiche of glamour and earth mother—alien-style. Anyway, it had the desired effect and audience and critics alike sent up a collective gasp. It is, after all both sexy and funny and I think that came across. There's also a tendency to see a pregnant woman as something delicate and fragile, so if you're seen doing anything out of the ordinary, it's somehow spectacular. Dancing would always get a reaction. In some ways the pregnancy almost overshadowed the album. It became a focus for the straighter press as something they could hook a story on in a country that rarely takes its music seriously enough.

Why do you think Australia doesn't take its music seriously enough?

I suppose it wasn't something that occurred to me until I moved to London where they do take their pop music very seriously. It's a broad church there—Radio 1 will play Bjork, Portishead, The Spice Girls and Babylon Zoo in one bracket. That would never happen here where the first two mentioned acts would be considered far too radical for a station playing the second two acts. In other words, people are spoon-fed. Perhaps it's because the function of radio now is to act as background noise in an office or shopping environment and anything that might jar and cause someone to turn the station is eradicated. So, radio doesn't take music seriously—it takes ratings seriously. The press will pretend to take music seriously, but in reality there are very few articles in the major press that aren't either rewritten publicity blurbs from the current visiting act, which have everything to do with haircuts and trashed hotel rooms, but nothing to do with how and why they fit or don't fit into a continuum, or articles devoted to the downward trend of music as a popular force. No-one sticks their neck out and discusses the music! Journalists in London do. Or perhaps it's their editors. However it works, the British have a tradition of exposing the world to new music and they're proud of it. The Beatles are a major part of their recent cultural heritage—perhaps the most significant offering to the world since the Westminster system, and this is never forgotten. New music is discussed in many forums and with much intellectual rigor. I wish it were the case in Australia.

With all the excitement about Lilith Fair and the rush of female artists on the global pop charts, many are saying women are more empowered than they’ve ever been in the music industry. What’s your take?

Certainly, I personally have never felt at a disadvantage being a female in this industry. Growing up, I easily had as many female singer-songwriters to admire as male ones. Women have been under-represented as instrumentalists, but this is changing with the new generation having grown up with plenty of role models. This industry has always been preoccupied with sex—it matters not what gender as long as you're able to strut and burn with charisma. Women have cornered the market lately with huge commercial success stories like Celine, Mariah, Alanis and The Spice Girls. And let's face it, whenever a record company smells a hit, they're on that bandwagon like they built it. I think we can all safely rely on a lot of women getting signed and whatever imbalance still remains tipping heavily in the female direction.

How have you changed as a performer and a personality since the Do Re Mi days?

I'm far more in control of my voice now and it has improved immeasurably. I play guitar on stage which I never did in Do Re Mi and that has altered the way I perform. I always felt straightjacketed as a frontperson in Do Re Mi. There were three other people's views to represent and a band persona to convey which wasn't entirely mine. So, as a personality I became much more relaxed as a solo artist and a lot more capable of addressing an audience and bringing them more into my sphere. These days, I consider Willy and I to be a band, but while musically we complete each other, how I communicate with an audience is not something he's concerned with.

Contrast your experience as a fashion model to working in the music industry.

I modeled for money. I was lucky to get paid so much for how I looked. I modeled while I was at university from the age of 18 through to 23. That was it—never anything other than a well paid sideline. I used to cop a lot of flack for not shaving my armpits—I always believed that I could change people's perception in that area—and not having a hairbrush. I never had a problem with either of those two things once I'd joined a band. I'd always prefer to be self-employed. It's miserable having other people tell you what to do even if you're being well-compensated for your trouble.

You worked with Pete Townshend on his Iron Man project. That was the most exposure you've had in North America to date. Describe the experience.

It was an offer made entirely out of the blue. He'd seen a Do Re Mi video at Virgin headquarters in London and gave me the role. He's a charming, erudite man with lots of stories and the sessions were easy and enjoyable. Ultimately though, I think the project was disappointing. The story is such an esoteric one that by the time it had been interpreted in song and then cut down to fit a record company budget, it became a pale version of what it might have been. The direct result happened some time later. Virgin, having got wind that I would do other work outside of Do Re Mi slapped a solo deal on the table saying that they wanted that before another Do Re album. The consequences were interesting. I made an awful record that never came out and the Do Re's were dropped from the label—not necessarily in that order.

Describe the attempts to get your music released in North America.

I lived in L.A. during 1989 and made the aforementioned album for Virgin U.K.—Virgin U.S. wisely kept their distance. When the shit finally hit the fan in London, I came back to Melbourne and put out String Of Pearls. There were attempts made with that record and Bitch Epic to interest a U.S. company, but to date no-one has gone the distance. I have played at the Austin South-By-Southwest [music conference] and met with dithering New York executives in consequence, but to no avail. Too weird or not weird enough?

You've done some acting in your time. What projects have you been involved in and what do you enjoy about the process?

A number of short films when I first started—student projects for film courses and one made by a lecturer and film maker named Peter Tammer, called Malacoota Stampede which went on to win a gold medal prize at the 1980 Melbourne Short Film Festival. Then there were a few small parts in feature films and then a large role as the hero's babe in a bad cult road movie about revheads called Running On Empty. In 1990, I was lucky enough to be cast as the Goddess Juno in Peter Greenaway's Prospero's Books singing a masque by Michael Nyman. I also performed in a Sydney Belvoir Street Theatre production of Aristophane's Frogs, directed by Geoffrey Rush. Though the roles have been many and varied, I don't think of myself as an actor. It's a novelty which I enjoy on an infrequent basis, though I'm always surprised when I get cast in something. I'm always waiting to be found out for the fraud I am. The things I like about it are the things I like about performing—showing off and pretending to be someone I'm not.

What's your take on the way the media is treating Michael Hutchence's passing?

I used to know him—not very well, but affectionately as a party friend and fellow traveler on the musical path. But we hadn't seen each other for a number of years despite having mutual friends. The media love to use phrases like "the exclusive Ritz Carlton"—the hotel he was found in—and their portrayals of celebrity are by necessity cartoon-like, unreal and cynical. I didn't see any British or U.S. press but the Australian press seemed to see in his death an opportunity to revel on the world stage of celebrity funerals. Maybe what I'm trying to say is that if Diana hadn't died and been given her state funeral, we wouldn't have seen Michael Hutchence's funeral on live telecast.

Any thoughts on the cult of celebrity as it stands in 1998?

It's a weird thing being famous for being famous. It is both unhealthy and cynical, but also harmless and Warhol-like. I think people court it as something desirable and perhaps believe that their lives will be more glamorous if more people are watching what they do. However, it must ultimately be disappointing and intrusive. This question is a thesis! But briefly, in my profession, publicity and subsequent celebrity is a two-way street serving to make my music known to a wider audience which will ultimately make it possible for me to make a living out of doing what I love. The challenge is where to draw the line at what is public and what is private information.