Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

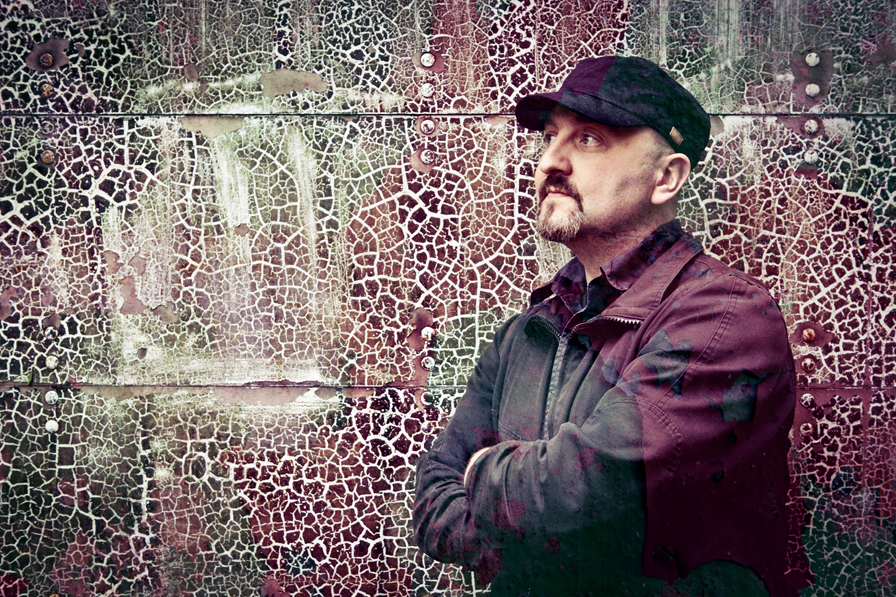

Colin Edwin

Nomadic Alliances

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2015 Anil Prasad.

For bassist and composer Colin Edwin, the muse never stands still. The British musician is best known as Porcupine Tree’s bassist, having helmed the low end for the progressive rock act since 1993 and across eight studio albums. Since the band went on hiatus in 2010, Edwin has pursued an impressive diversity of activity. He currently has seven simultaneous projects happening, each crisscrossing multiple genres, approaches and personalities.

Twinscapes finds Edwin working with bassist Lorenzo Feliciati, alongside several guest artists, including Roberto Gualdi, David Jackson, Nils Petter Molvaer, and Andi Pupato. Its self-titled debut album, mixed by Bill Laswell, showcases the engaging possibilities two expansive bassists can pursue as a unit. Twinscapes' music situates the full spectrum of frequencies Edwin and Feliciati can generate through their instruments within electronic, atmospheric and jazz-influenced territory.

Edwin’s partnership with guitarist, composer and producer Eraldo Bernocchi, has yielded two significant projects to date. Metallic Taste of Blood is an exploration of the darker side of the musical psyche, combining the worlds of metal, dub and experimental jazz into a single universe. Obake goes even deeper into the metal realm, featuring heavy riffs meshing with electronica, ambient and noise influences.

Another major collaborative effort is Edwin’s work with the Ukrainian duo Astarta. In this project, Edwin takes vocals by Inna Sharkova and Yulia Malyarenko, and blends them with Western melodic and rhythmic constructs. Edwin was given license to take Astarta’s Ukrainian folk elements and infuse them into completely unrelated contexts. Everyone involved was enthusiastic about seeing how far Edwin could evolve the group’s sound from its origins. The collaboration has yielded a digital single titled “Kalina,” released under the name Astarta/Edwin, with a full-length album forthcoming.

Guitarist Jon Durant, who appears on the Astarta/Edwin recordings, is also Edwin’s partner in Burnt Belief. It just released its second album Etymology, an instrumental effort that bridges Middle Eastern influences, intricate textures, deep grooves, and live and electronic percussion. Burnt Belief is an area of significant focus for both musicians, with major video accompaniment created for key tracks such as “Dissemble” and “Semazen.”

Endless Tapes, in which Edwin teams with multi-instrumentalist Alessandro Pedretti, is a more minimal affair. It focuses on cyclic, circular musical concepts, with a strong rhythmic underpinning. The pair’s pattern-based style also veers into the deeply melodic, providing an emotional element that creates balance with its more eclectic elements.

In addition to all of this, Edwin is readying a new solo album titled Infinite Regress. The album is solo in virtually every sense, with Edwin creating the entire musical landscape. He refers to the approach as “night songs.” Edwin elaborates on that description and the rest of his extensive output in this conversation.

You’ve referred to yourself as a “serial collaborator” as of late. Describe the journey from band life to this new way of working.

For many years, I’ve been in a band situation with Porcupine Tree. I’ve also been working with Geoff Leigh in Ex-Wise Heads for a long time, but I only really had those two things going on. I’ve found it valuable to play with different people and I’ve been pleased with the results. The other parties have been as well. Collaborations have really expanded my thinking and confidence. They’ve also let me explore what’s musically possible for me. It’s a very nourishing thing from a creative point of view. It’s very different from being in a long-term band situation. I’ve realized how differently other people do things. I’ve also realized that I’m more adaptable than I thought I was. [laughs]

One of the first things I did was work with Jon Durant on his Dance of the Shadow Planets album from 2011. That was an interesting one. I was sitting on an airplane to Boston thinking “Why is Jon asking me to work with him? He lives in Boston and it’s full of musicians, including those at Berklee.” Jon had a lot of confidence in asking me to come all the way from England when we’d only met very briefly, previously. He heard something in what I did and that meant he wanted me specifically on his project. He was going a long way to find someone to fit in with his material. It went really well, but initially I wondered “Is this going to work?” But it was a natural thing and it was absolutely fine. The same thing happened with Eraldo Bernocchi. I didn’t know him. We had met a few times and chatted on the phone. Within a half hour of working together, everything was fine. We quickly found our M.O. and way of working. Things keep getting better and better the more I work with both Jon and Eraldo.

Tell me about the musical concept behind Twinscapes.

For a long time, I wanted to do something with another bass player. The bass can be quite a limiting instrument in some respects. You typically have a very set role in a band situation, but there are lots of other things I like to do, including using effects. I don’t have a super slap-tap technique, but there are a lot of textural things I like to do on the bass. There are also a lot of sounds I like making that don’t get an airing in a group setting because they’re not appropriate. I never used many effects in Porcupine Tree because the group was already very sonically dense with keyboards and multiple guitars. Also, if I stepped too far out of my role, the band wouldn't have a solid bottom end.

During my wondering about the possibilities of working with another bass player, Giacomo Bruzzo, who runs RareNoise Records, contacted me. Giacomo is an amazing guy with a deep love of interesting music. His mission is to put out stuff that doesn’t easily fit categories. That’s a really brave thing in this day and age. Giacomo asked me if I’d be interested in doing a gig with Lorenzo Feliciati, a bass player I was familiar with. I enjoyed his band Naked Truth. Nothing moves things on like having a deadline, so I thought “I’ll give it a go and get in touch with him to see what we can do.” It was a very quick, spontaneous thing when we did our first gig in March 2013 in London. We had to come up with a lot of material fairly quickly. We also had a very short rehearsal, which we mostly spent sitting around talking. [laughs] Then we got up and played. The results were great. In fact, I thought they were magic. It can be difficult working with other musicians sometimes, which has nothing to do with how good you are. It’s how good you listen. A lot of people can play their instruments, but they don’t seem to have the awareness of the space they occupy when they play with someone else. I like to think that’s something I’ve developed. Lorenzo definitely has that. He’s a very sensitive musician who doesn't want to overplay over everything.

After that gig, we realized we fit really well together and enjoyed it. Giacomo said “Why don’t you do a record?” So, it grew out of that. There wasn’t a conceptual discussion. Lorenzo had a similar sort of idea. He likes to do textural things, and he has a few techniques that I don’t have like fake harmonics, which make you play in a much higher register. So, we both like a lot of the same things, but have enough different influences that we can encourage each other in certain ways. Twinscapes has been a really productive experience for me and made me think about the bass and possibilities in new ways.

Is there a creative challenge to deal with in that you and Feliciati occupy similar sonic spectrums?

For sure, but it just seemed to be quite obvious that if Lorenzo was going to play a fat, heavy, low bass line, that I would do the opposite. It was almost unconscious. It was very easy to follow him, and I think the same was true for me. When we were recording, there were a few pieces in which he had some big, heavy Octaver bass lines going on. I thought “Great, that’s an opportunity for me to use some of these ridiculous pedals I’ve got that I could never use in a band.” I have a sitar emulation pedal which is fantastic for making drones and EBows that let me make very haunting textures. I’d combine that with delay and chorus to make interesting sounds. I wouldn’t do that in a band with a keyboard player, because that stuff would get lost completely. But with the two of us, we have that sonic freedom. So, what might seem like a limiting situation is actually liberating. When one of us is playing a bass line, the other can do a lot of other things.

Tell me about Bill Laswell’s contributions to the Twinscapes album.

If you had said to me when we were making the recording “Who would you like to mix it?” I would have instantly said “Bill Laswell.” At the same time, I thought “There’s no chance of that.” But he agreed to do it and really brought a lot of power and clarity to the mixes. I can’t think of anyone who could have been better to have mixed the album, particularly given the fact that he’s a bass player. He was going to look after the bottom end in the mix and understand what we’re about it. Bill said he understood the territory. There’s a similarity between what we do with Twinscapes and some of Laswell’s work. Bill provided some nice compliments about the project as well. He said he enjoyed doing it and was pleased with what we gave him, sonically speaking.

The Twinscapes recording features some notable guest appearances. How did they come together for it?

We thought we should have some other soloists to expand the sounds of the record a bit. I’ve been a fan of Nils Petter Molvaer for a long time. I thought it would be fantastic to have trumpet on the album. He was in London preparing for a week of gigs as part of a Norwegian festival in 2013. I was fortunate enough to meet him through Giacomo at RareNoise. Nils was very enthusiastic about Twinscapes and we sent him the stuff. We thought he’d be too busy to do it, but he got back to us and what he gave us was perfect. Roberto Gualdi from PFM on drums also did a fantastic job. We were working with programmed drums on a couple of tracks, but felt we needed a real person. Andi Pupato is another really interesting contributor. I’m a big admirer of his work with Nik Bärtsch’s Ronin. We felt it would be good to complement the electronic beat stuff with live percussion. He was very Swiss and precise, sending back amazingly well-recorded stuff that was really well thought-out. We didn’t have to do any editing or post-production. Andi brought some life to stuff that was in need of other sounds. I was also really happy to have David Jackson on the album because his stuff is unique and a bit eccentric. We sent him a couple of things to see what he might want to contribute to, and he chose the track “I-Dea,” which was a great vehicle for him.

You’ve been working with Eraldo Bernocchi across several projects in recent times. How did you first connect with him?

We first communicated through MySpace a long time ago before it became a graveyard. You used to be able to have meaningful conversations there without being spammed. The initial point of contact related to me being a fan of a record Eraldo made called Parched. I found it through a random trawl through MySpace, looking through pages seeking interesting music. I bought the album through RareNoise as a customer and it ended up on a playlist of mine. Eraldo and I connected and when Porcupine Tree were in Italy once. We met up and got on really well. Straight away, Eraldo said “Why don’t we do some work together?” He also said “You must meet Giacomo at RareNoise in London.” Since then, both of them have become friends and collaborators.

Describe the general concept of Metallic Taste of Blood.

I have a real love of music that’s often quite unsettling. A lot of Metallic Taste of Blood is darker, industrial music that’s not exactly what you’d call easy listening. [laughs] At the same time, it’s quite satisfying. The group is a vehicle to make some sounds that are quite brutal at times. We can explore a certain noise element that we find appealing. I liken it to watching a horror film. The film can be unpleasant at times to watch, but at the same time you might quite enjoy it. As far as the name of the band, it’s similar to when you might have a cut inside your mouth. There’s something a little bit disturbing about having blood in your mouth, yet it’s not entirely unpleasant. It’s a bit abstract. [laughs]

Going deeper into this idea, there is unpleasantness all around us. You can ignore that unpleasantness, but it’s still going to be there. The world’s quite a scary place. Having music that’s quite dark is a bit cathartic. When you turn on the news every day, the violence going on in humanity Is unbelievable. And the fact that our Western standard of living is supported by a whole range of things in the world that are very uncomfortable is something most people avoid contemplating. It’s uncomfortable subject matter that the music deals with in a broad, conceptual way. It’s music that has a lot of discordance, but we set that off against moments that are very harmonious as well.

What can you tell me about the forthcoming Metallic Taste of Blood album?

It’s as yet untitled, but it’s all mixed and scheduled for May 2015 on RareNoise. My feeling is that it's a darker, heavier and harder sound than the last one. Ted Parsons on drums has given us a leaner sound and Roy Powell's keyboards are much more atmospheric and less upfront than Jamie Saft's mainly piano-focused parts on the last album. The music has a lot of contrasts. As before, there's a firm dub influence in places and plenty of heavy discordant riffs with noise elements, but there are also ambient moments in which Eraldo makes his guitar sound quite fragile and almost angelic.

You contribute to Obake’s recent metal-oriented album Mutations, also featuring Bernocchi. Provide some insight into the group and your role on the record.

It’s metal, but not metal, as weird as that may sound. I think there’s somewhere you can still go with metal, as Obake demonstrates. I came a little late to the party, so a lot of the music was already quite well developed by the time I came on board. I was able to focus on some of the existing improvised structures and some of the thematic elements with fresh ears and develop them a bit, so they sound more structured and composed than they were before. This gave Lorenzo Esposito Fornasari, the vocalist and composer in the project, the opportunity to further expand some parts.

Obake is by far the heaviest, most elemental thing I have ever been involved in, but I found the music instantly intriguing. There are a lot of non-linear structures in the tunes and Lorenzo uses his vocals much more as an instrument than thinking about lyrics, He even refers to the material as "non-songs." I find his approach just as powerful as having explicit vocals with a clear meaning, as it really penetrates into your subconscious somehow. The combination of primal riffing mixed with an almost classical textural sensibility is also very seductive. Obake is also a great format for me as a bass player to concentrate on just being powerful and direct and trying for a really big sound, so I’m using a down-tuned bass exclusively, with lots of distortion. We've just played a short run of European gigs with Jacopo Pierazzuoili from the band Morkotbot on drums. The material is proving to be very flexible and engaging live. There will be more gigs in 2015, for sure.

How did you you first become aware of Astarta?

Ex-Wise Heads had an offer to play a festival in Crimea in the summer of 2011. Crimea has been in the news for all the wrong reasons, but it’s a very beautiful region and an ideal setting for festivals in the summer. It has good weather and is on the Black Sea. It was an area I didn’t know anything about, but we were contacted by someone who seemed very legitimate. The festival he was representing had lots of other artists booked. Everything looked very cool. Fast forward slightly and as the festival got nearer and nearer, more and more alarm bells were ringing. I noticed people were dropping off the bill and the organizers got more and more unreliable with the arrangements. I ended up not going because it felt like a disaster waiting to happen. These kinds of things happen sometimes in countries with big language barriers.

Fortunately, through that situation, I met another guy named Igor Romanov who puts on gigs there. He said “I’d love to get you over to Ukraine. I understand if you don’t want to come, but we’re not all disorganized and a nightmare to deal with.” So, I agreed and went with Geoff Leigh as Ex-Wise Heads and also with Tim Bowness’ Slow Electric project. It was a double bill which went really well. During that Kiev event, I got introduced to Eduard Prystupa who told me he’s working with Ukrainian folk musicians who wanted to collaborate with me. I said “I don’t know anything about Ukrainian folk music, but I’m curious to hear it.” He sent me some vocal tracks, which were the two female singers, Inna Sharkova and Yulia Malyarenko. When I opened the files, I was amazed by their sound. They’re singing very close harmonies and it was really interesting from a rhythm perspective.

Tell me about the creative process when working with Ukrainian folk music.

As a creative exercise, I thought I’d see if I could do something with these vocal files. We ended up doing a track together and I got a great response from everyone I played it to. Everyone on the Ukraine side seemed to love it as well and I was asked to do more. So, over the last couple of years, I’ve been sent more mainly vocal parts and I’ve put stuff to it. Sometimes, I have to listen to it for quite awhile, but I’ll eventually put something to it that reflects what the rhythm and tempo suggests to me. It’s quite an interesting thing to do. The Astarta singers have done lots of work with Ukrainian musicians, producers and acoustic bands. What they said to me is that it was very interesting to work with someone who didn’t treat their music as folk music. I’m coming at it from a different direction. It’s proper collision music. I’m not referencing any of the things Ukrainian people would naturally do. I’m taking it somewhere else for them. It’s really interesting for everyone involved.

There’s a lot of intriguing stuff happening rhythmically with Astarta. For instance, a tune can have a bar of seven followed by a bar of six, another bar of six, and then another bar of seven. So, it’s 7-6-6-7 through the whole tune and vocal melody. It can be confusing, but it also flows when you hear it. I try to have my bass playing latch onto it all. When listening to the vocal melodies, I’ll hear a basic rhythm thing I can follow. Eventually, I make sense of the phrases and can build things up from where I hear the root harmony. Sometimes that might suggest a contrast section I create. In Ukraine, they’re fond of odd phrase lengths. Things are made even more complex by the fact that I don’t always know what they’re singing about. Sometimes I have to make sense of things on my own and draw up something like a skeletal bass line and chord sequence I can build things from.

Sometimes they send me more developed ideas. Ukrainian folk music seems to be full-on from the moment they start playing—everyone is going crazy. It’s very vibrant and up-tempo. They kick it off at 100 miles per hour and don’t have a half-time thing going on. It just carries on. Sometimes, I strip things away and half-tempo it so I can give it a different perspective. Once, they wrote to me and said “You’ve made this song sound very sad. It’s meant to be a wedding song and quite happy.” I said “I just hear it that way, harmonically and rhythmically. It sounds completely different to me. It doesn’t sound like a happy tune.” It’s cognitive dissonance. It’s nice to bring that color to things.

How has the crisis affecting the region impacted the project?

For the moment there are no plans to do any further live performances, but we're in touch and I really hope the situation improves. The good news is that I have just been in touch with Comp Music/EMI in Ukraine who are keen to see if they can organize an album release in conjunction with their partner labels in other territories outside Ukraine. This is not just because the music industry in Ukraine has pretty much collapsed, making a domestic release almost impossible, but also because I think they're keen to present something positive from their country. Just over a year ago, most of us in the West rarely heard anything about that part of the world, but since the Euromaidan Revolution, the news has been regular, as well as consistently and relentlessly awful, and they are of course very aware of that.

I understand you experienced a situation that revealed some of the issues at work in the country.

I once had a crazy experience in April 2013 in which we were shooting some promotional stuff for Astarta in Vyshgorod, a little outside of Kiev. There was a big frozen lake on one side of this location and on the other side there was a great big walkway. One of the guys, Igor Romanov, said it would be a fantastic place to film. He said “I’ve got a friend with a helicopter with a camera on it.” It was actually a toy drone with a GoPro camera attached to it. [laughs] He thought it would be great to film us on the lake with the camera taking photos from above. I said “Okay, this is quite an interesting idea.” So, we’re standing there for 20 minutes and all of a sudden, a jeep pulls up with these heavy-duty security people. They’re really unhappy. I don’t know what’s going on because I don’t speak the language. Next, more and more plain clothes guys turn up, as well as security guys in full combat uniforms with guns. And then big trucks full of uniformed police show up. I lost count at about 21 people.

It turns out this toy drone was picked up by the presidential security system because the place we chose to do our promo shots was 10 kilometers from where the former president had just been deposed. So, we ended up sitting in the back of a car for four hours while different police departments photographed this toy drone. They took out the memory card from the camera and went driving off. They were also checking out my driver’s license, which doesn’t mean anything to them because it’s not in Cyrillic.

This incident gave me some insight into the security situation. Obviously the president was totally paranoid. He had employed all of these different security people and they thought the toy drone was some kind of guided missile, even though it’s something you can buy in a toy shop over there. It became clear no one wanted to make a decision. None of these security people wanted to say “It’s okay, let them go.” At the end, my friends were embarrassed that this had gone on. They suggested we go for dinner in the center of Kiev. So, we get in the car and go for a drive and the guy gets pulled over again and shaken down by a police officer telling him his car is stolen. There’s obvious corruption going on. Any country that spends huge amounts of money on security and police usually has something going on that’s not quite right.

How did Jon Durant get involved with Astarta?

I had completed a couple of tracks for Astarta and they were put online to see if anyone was interested. Jon wrote to me. We had been working for awhile and he said he really liked the music and asked if he could play some guitar on it. At that point, I didn’t think of it as anything other than an experiment. I didn’t think about getting other musicians involved. I said “Sure, have a go.” Jon always does a great job and was very sympathetic to the material. It’s quite satisfying, because it’s unusual for Westerners with a background in rock to be involved with it. The Astarta music, even with its unique time signatures, is still accessible to casual listeners. It’s not difficult music to hear. It’s very uplifting and soulful. Jon has played on all of the material we have going on. Jon and I seem to have a great musical connection. He fit in fantastically with the Astarta stuff. Pretty much everything he gives me for the tracks is perfect. I should mention we also have other guest musicians on the material including Steve Bingham on violin and Pat Mastelotto on drums.

The first, self-titled Burnt Belief album with Durant initially took a more programmed, loop-based approach. It evolved into a more live sound for the new release Etymology. Tell me about the progression.

I quite like electronic programming as a process. A lot of people are bored by the idea, but I find you can be quite creative with it. I’m used to doing it as a bass player. I don’t always have a drummer on tap and I like to have rhythmic things to play to. So, I got into it out of necessity. You can make some great noises and sounds. I like to do it almost as much as playing bass. With Burnt Belief, it’s more of a remote construction. Jon and I worked live in the studio on his Dance of the Shadow Planets album. It’s because we worked so great live that we felt it didn’t seem so necessary to get together in the same room for Burnt Belief. It didn’t seem to matter that we weren’t doing it in real time. Jon and I are able to do some different things together. I really like his 12-string acoustic playing. I was aching to play a bit of double-bass. Those are both things we don’t do enough of and it was great to integrate that into the Burnt Belief sound.

The new album is definitely an evolution. We decided to have live drums on it. Dean McCormick, a friend of mine, and Vinny Sabatino play on it. Jon’s worked with Vinny for a long time. So, that’s made the sound more closer to the rock world, but it remains quite ethnic in places. Having a full drum kit gives the music a different perspective, but it’s still about what I do with Jon and his cloud guitar. Jon plays some great solos on it. He has excellent, very unexpected phrasing for a guitar player. It’s not rooted in a blues perspective, but more of a progressive rock and ambient one. Jon tends to do a lot more atmospheric stuff and I’m more involved in the rhythmic aspects of it. We’re always surprising each other and I think the album displays organic growth between the two of us.

I understand you’re working on live shows for Burnt Belief.

Jon and I did a one-off live performance in Chicago last October. Musically, we are confident it works very well live. We're hopeful we can do some European dates in the latter part of 2015, perhaps in conjunction with the Swiss band Sonar. We’re both big fans of their music and it would be a highly-compatible double bill.

You explore another universe of melodicism and minimalism on Endless Tapes. Describe the vision behind that collaboration.

Endless Tapes is another occasion in which I was contacted by someone and what he sent me interested me enough to move forward. Alessandro Pedretti is an Italian multi-instrumentalist who’s very interesting. He’s a drummer primarily, so his take on things is very rhythmic. He’s quite into rhythmic cycles and pattern-based approaches. That appealed to me quite a lot. I’m a big fan of music like that, including stuff from Nik Bärtsch, Sonar and Dawn of Midi. Alessandro has a very minimal approach to the drum kit. He just has a kick drum, snare and a couple of cymbals. There’s no big toms or anything. I felt I could flesh out his rhythmic ideas almost as soon as I heard them. So, we worked collaboratively over the Internet. Then he came to London and met up. It has grown from there and we’ve managed to make it into a live thing, expanding it into a four-piece band. It’s quite exciting to take something like this into the live world and give it another dimension. We had a live, conceptual visual thing going on with the shows too, which was a great addition.

Give me some insight into the upcoming second Endless Tapes release.

The album is fully mixed and mastered. It was actually ready a while back but I held off releasing it since I felt another instrumental album in 2014, after Burnt Belief and Twinscapes, was just too much. I’m planning to release it in the first half of this year. There's a certain geometric, cyclic shape to a lot of the music, with minimalist bass and drum grooves with lots of interlocking melodic parts. I feel it's a nice fit with the material from the debut release. It's all instrumental apart from the occasional wordless vocal from Alessandro.

What can we expect from Infinite Regress, your forthcoming solo album?

What I like about collaborations is people bring things out of me that sometimes surprise me. But I also like the opposite situation, when it’s entirely about me. I enjoy the OCD ritual of sitting and programming rhythm parts and making textural sounds. I always use the analogy that creativity is like a muscle. So, I always try to constantly do something. In this case, it’s creating something with little outside input. I have my vocalist friend RJ from another one of my projects, Random Noise Generator, on it. He’s shown a vastly different side of himself on this album compared to the “shouty” style of that band.

We've settled on the description "Night Songs," which seems to explain the territory—atmospheric songs perhaps best suited to headphones while driving or walking through a city at night. I am using a lot of sounds that appeal to both RJ and myself, including analog drum machines, dubby baselines, atmospheric EBow sounds, electronics, and guitar effects. The lyrical themes reference the increasing disconnections and distractions we all face with our seemingly ever-invasive technology and also the impermanence and unreliability of memories. There is a little bit of an ‘80s undercurrent as well—New Order meets Massive Attack, with a nod to Depeche Mode perhaps. It’s detectable but not overt. I’m planning to release it on my own label by mid-year.

What’s your perspective on the status of Porcupine Tree?

The status is we haven’t had any discussions on when to do anything. At the moment, the band exists as an entity. I hope we won’t leave it too long, because we really have put a lot of work into building up the band. I know there still is a lot of interest in Porcupine Tree. It would be a shame to let that pass. We haven’t had any discussion about knocking it on the head. I think at some point there will be more Porcupine Tree, it’s just a case of when. I don’t think it’s anytime soon. I’m not going to hang around and wait for it, because everyone is doing their own thing.

I think the band has real chemistry. When we made The Incident, we spent a couple of weeks in the studio. It was just the four of us working up the material and coming up with new stuff. It was very productive. I don’t doubt that would be the case again if we got back together. I don’t think we would be scratching our heads wondering what to do. I’m sure we’d come up with something good.

Not everyone looks back at The Incident favorably. What’s your take on the album?

At the time we made it, I felt it was the best mix of old Porcupine Tree, by which I mean Chris Maitland-era stuff, and the newer direction with more metal elements. I used to refer to it as the most complete album. But after having to play it night after night as a complete thing, the gloss wore off a little bit for me. I thought the problem with it is a lot of the material didn’t work when we took it out of context. When we did a festival date and did a part of The Incident, it wouldn’t feel right. When we played the whole thing, it felt very strong and complete. Now, I look back at it and don’t think it’s the best Porcupine Tree record. I don’t know what is. It’s difficult when you’re involved with it. I like In Absentia. It was a very exciting time to go to New York and make an album with a decent budget. I really like Lightbulb Sun too. There’s a kind of adventurousness to that one.

What are your thoughts about the group’s legacy to date?

I’m very happy to be in a band that people care about. I still get messages from people who love the group and want to get details on what I played on various tracks. I think everyone in the band can look back on it and be quite proud of it. Most bands don’t get anywhere near as far. We’re also fortunate to look back on the records and realize that a lot of them have stood the test of time. Porcupine Tree has been an amazing thing to be a part of, whether or not it does anything again. It’s been a fantastic journey and I think all of us would agree we achieved more with the band than we ever thought was possible.

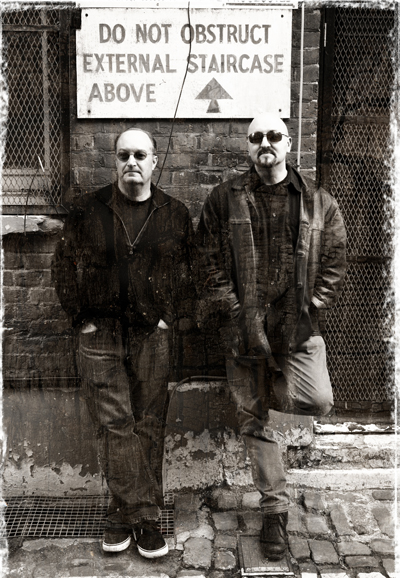

Jon Durant on Colin Edwin

How did you first connect with Edwin?

I first met Colin when I brought my son to a Porcupine Tree concert in New York. I contacted Tony Levin to see if he'd ask Colin if we could get passes so my son Matt, who plays bass, could meet his favorite bassist. We ended up having a wonderful chat. Colin was really generous with Matt and he and I really discovered a lot of common ground. Since then, we remained in contact, and we stopped by to say hello at a few later shows. He is, simply, one of the most delightful, grounded and interesting people I’ve ever met.

Since we’ve started working together, I’ve also found him to be an incredibly creative, interesting and unique musician. He’s got such a great vibe with his programming, to say nothing of his really fabulous bass playing. The Astarta material also shows the great range of his creativity—virtually all of that material is him taking the singers’ melodies, and turning them into full pieces, with really nothing to go on but their voices. I’ve really enjoyed being a part of that project. It’s been amazing to witness it take shape. What’s also nice about that one is that he’s always left everything wide open for me to do my thing.

What’s your perspective on the creative process that informed the new Burnt Belief album?

Much of the material on Etymology began with my cloud guitarscapes. Colin would listen to them, and find the bits that really leap out at him and start building rhythm tracks around them. In some cases, he would take my ambient cloud textures and run them through a slicer to create rhythmic ideas, and then build tracks around them. After he’s come up with some rhythmic ideas, the tracks come back to me for melodic and harmonic content, and putting things into some kind of form. At that point, we would then finalize our parts, and brought in the guests for their parts.

What makes Edwin a unique collaborative presence for you?

When we first started working together on my album Dance of the Shadow Planets, it immediately became apparent that he and I seemed to have a strong musical bond. We share a lot of similar musical background. Rather than simply showing up and playing the tunes, he really dug in and created his own space within them. On our subsequent recordings, he and I have gained a great understanding of what makes the other one tick, so he will often come up with something and think “Jon will have fun with this.” Neither of us feels the need to make our demos complete, in the way that we often have to with others, because we know that each of us can take it and run.