Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

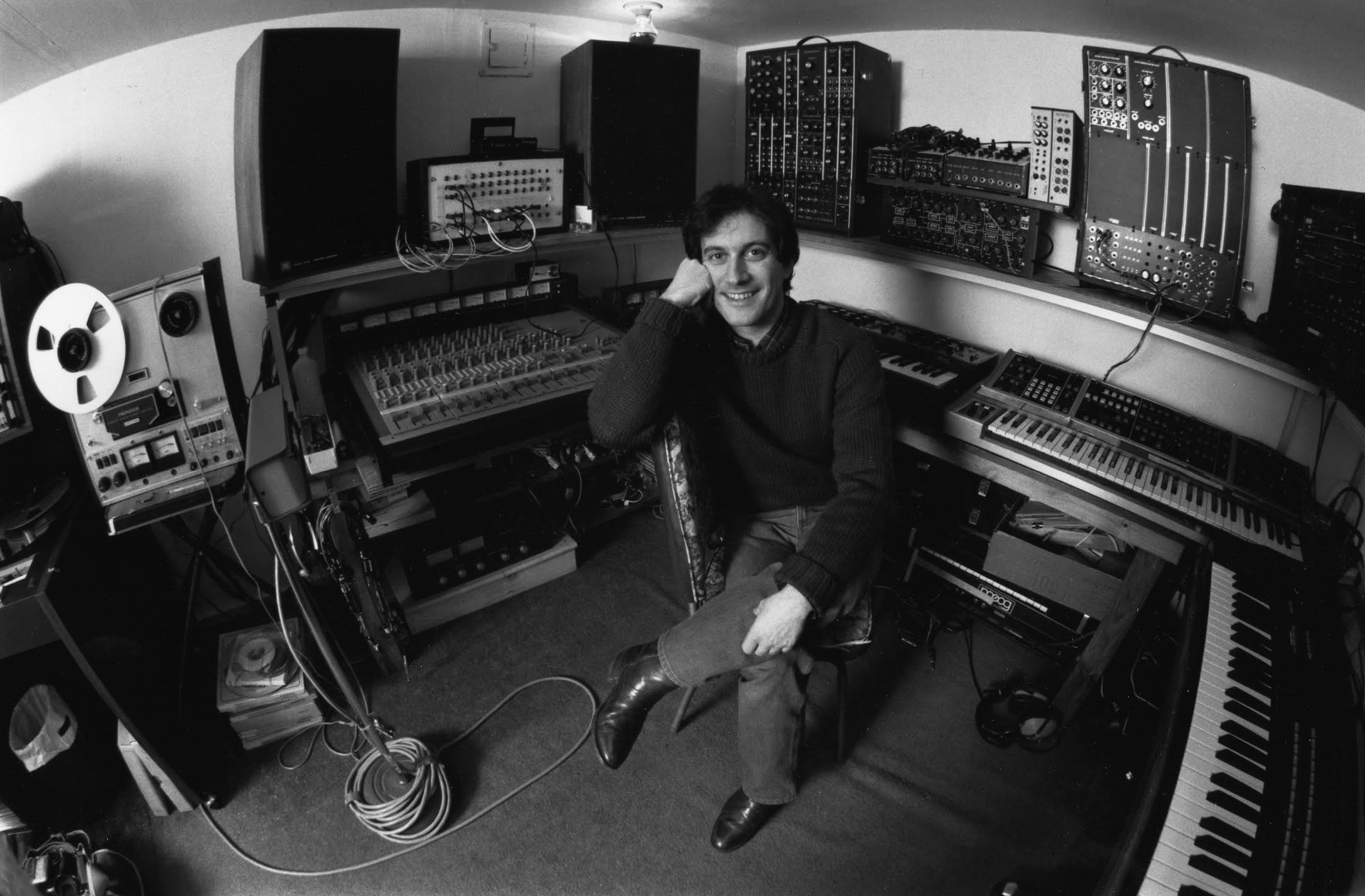

Larry Fast

Evolutionary Snapshots

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2004 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Dion Ogust

Photo: Dion Ogust

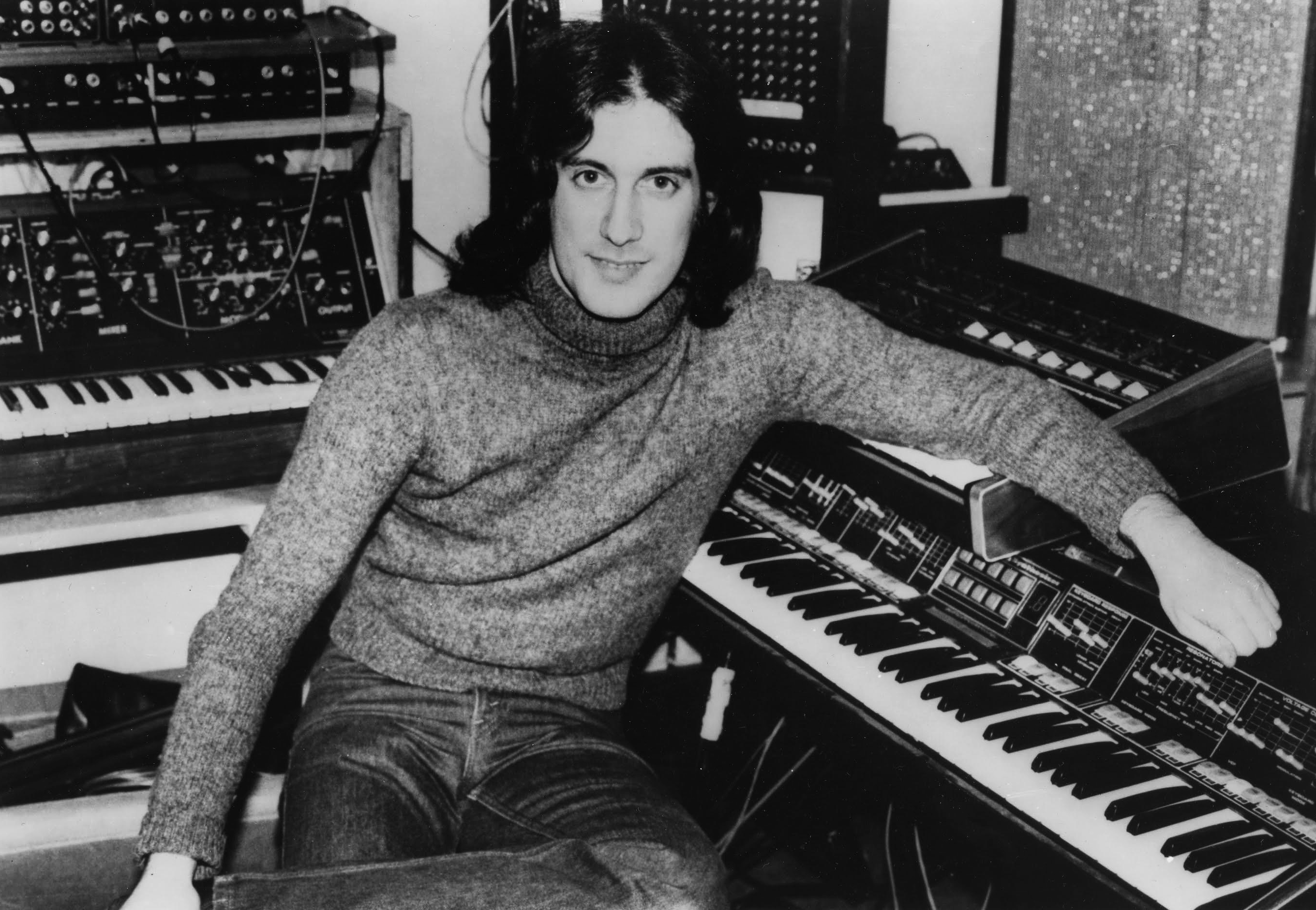

Putting a human face on technology is electronic music pioneer Larry Fast’s specialty. Since 1975, he’s released 10 albums under the name Synergy that set new standards for synthesizer-based composition, as well as pushed the technology envelope. Most importantly, the records proved that electronic music could sound just as organic and expressive as anything created with acoustic instrumentation. Those landmark albums were just reissued by Voiceprint in expanded, remastered editions with the aim of ensuring 21st Century ears have access to them for a long time to come.

The first Synergy album, 1975’s Electronic Realizations for Rock Orchestra, grabbed the attention of adventurous music lovers, as well as several high-profile musicians. Shortly after its release, the British progressive rock act Nektar asked Fast to join its ranks and he stayed on for an album and tour. Fast then received a career-propelling call from Peter Gabriel. He soon found himself part of the ex-Genesis vocalist’s new band—a relationship that stretched into the mid-‘80s, manifesting itself in extensive touring and recording. Fast is responsible for many of the sonic imprints that helped shape Gabriel’s third and fourth albums into the classics they are today.

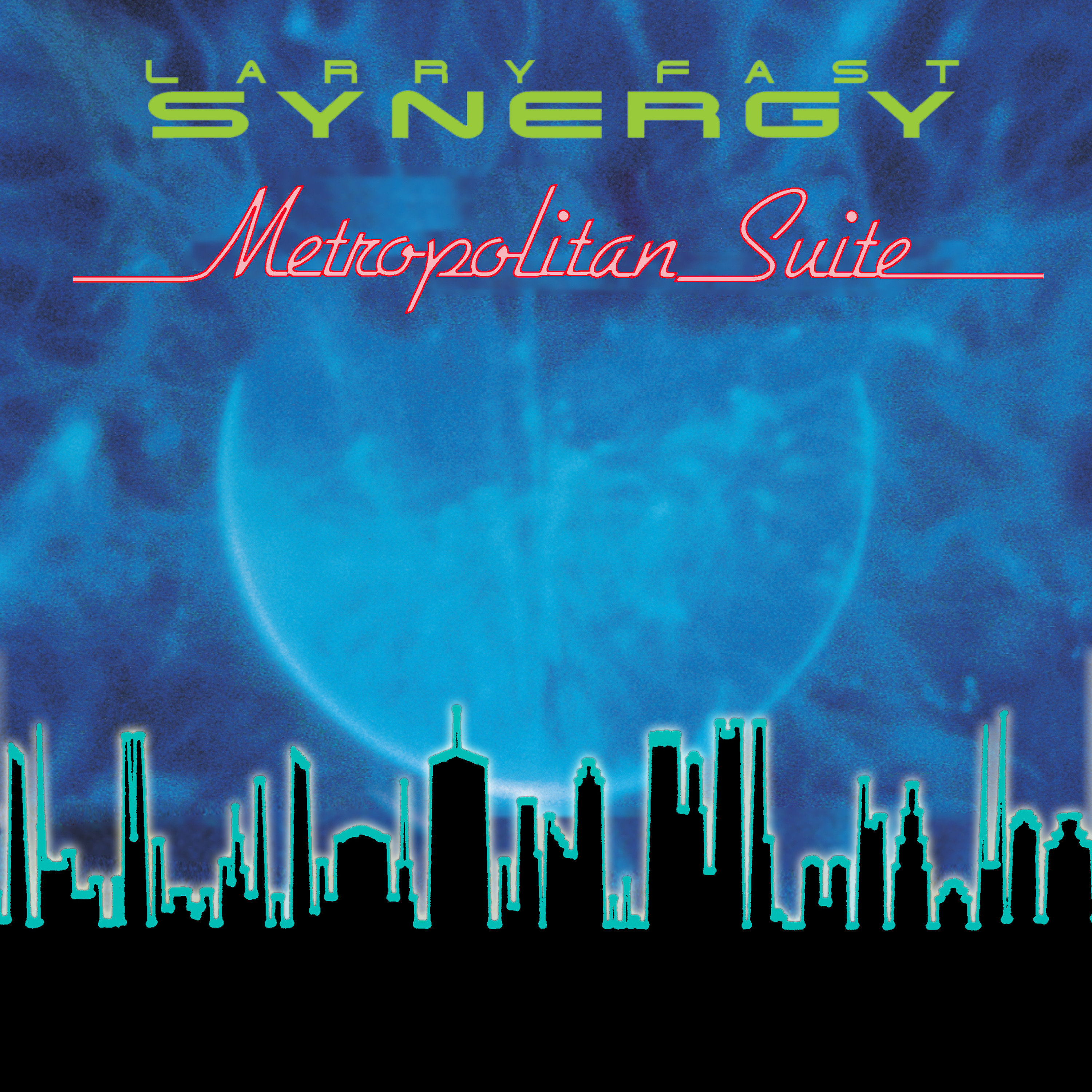

In addition to Synergy and Gabriel projects, the '80s saw Fast involved in a wide array of studio work for the likes of Kate Bush, Foreigner, Hall and Oates, Annie Haslam, Meat Loaf and Barbara Streisand. Towards the end of the decade, he released what many consider to be his masterpiece: 1987’s Metropolitan Suite. With its cinematic feel and expansive melodic approach, the disc remains one of electronic music’s finest hours.

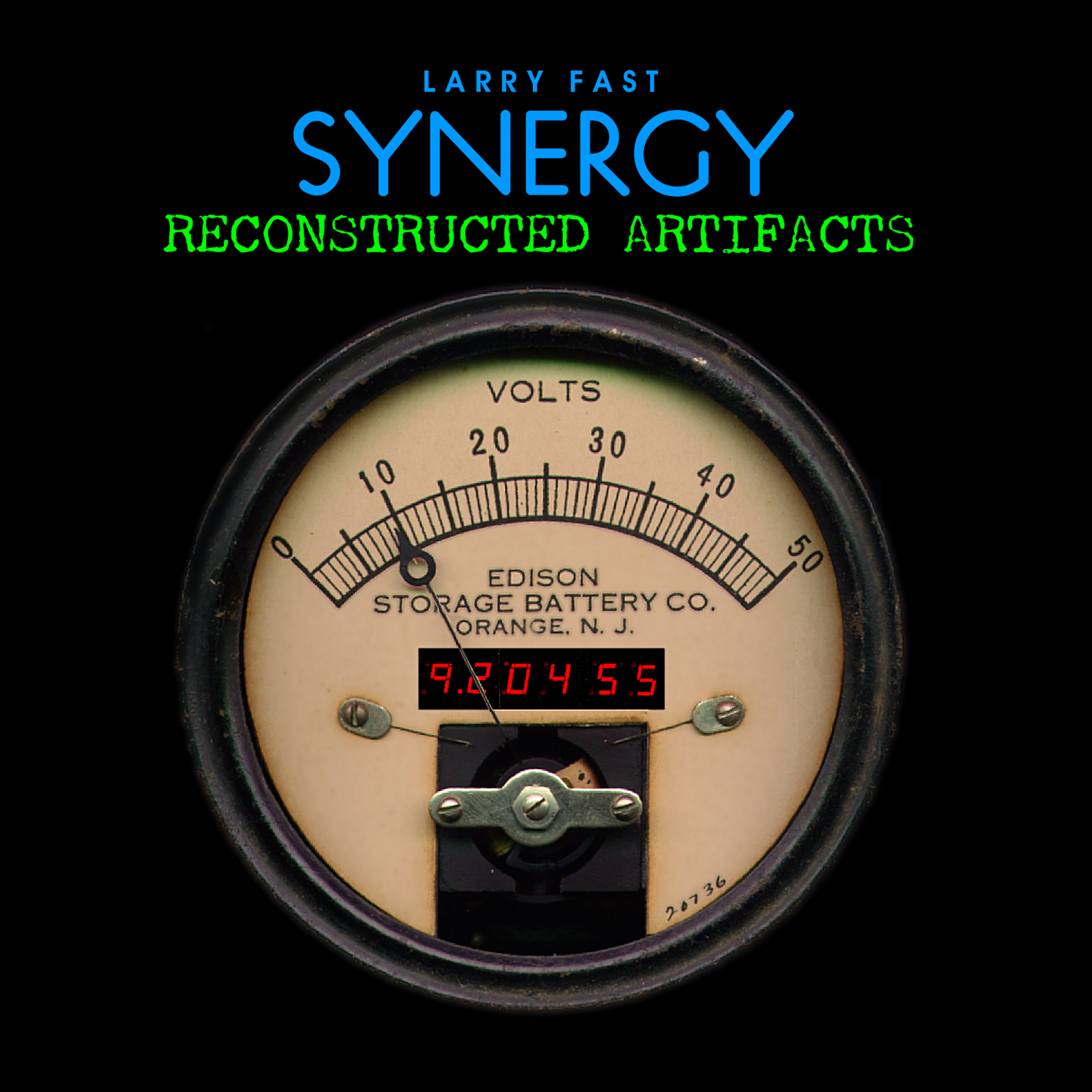

It would be another 15 years before the next Synergy release. It arrived in the form of 2002’s Reconstructed Artifacts, a disc of re-recordings of earlier Synergy works using the latest digital synthesizer technology. The disc was initially designed to serve as a souvenir for people attending the debut Synergy concert held at the 2002 Alfa Centauri festival in Holland. Popular demand ensured a worldwide release soon followed.

Fast has kept busy between Synergy projects. He’s made significant contributions to the XM Satellite Radio network, including designing its broadcast sound logos. He also played an important part in creating the music for Disney Sea, a new Walt Disney theme park based in Tokyo. In addition, he’s toured and recorded three albums with the Tony Levin Band, which also features drummer Jerry Marotta and guitarist Jesse Gress. He's also involved in designing assisted listening devices for the hearing disabled.

Innerviews began this in-depth conversation with Fast by exploring the new Synergy reissues.

Photo: Kevin Scherer

Photo: Kevin Scherer

Tell me about the thoughts and philosophies that went into the latest rereleases.

Since they had been around awhile and got the full digital remastering treatment in the late ‘90s with the release on Polygram, which then went to Universal, it seemed important to come up with something that made them a little more interesting this time around. So, several of the CDs now have bonus tracks that are either alternate mixes, radio edits or, in a few cases, earlier demos of what showed up on the albums eventually. I wanted to keep the integrity of what had been the original album, with one exception, which I’ll explain in a moment. On all of the new reissues, the extra pieces were placed after a 10 second gap after the original album as it was originally constructed. I see it as the audio equivalent of a DVD that has trailers, behind-the-scenes bits, outtakes and that sort of thing. The only one this doesn’t hold true for is Electronic Realizations for Rock Orchestra. That’s because in late 1975, the European label chose to add an earlier version of “Classical Gas” to its release of the Electronic Realizations LP. The track originally appeared on the second Synergy album Sequencer in the States. The European label put the track in the midst of the original running order used on the U.S. version of Electronic Realizations. So, for the Voiceprint reissues, I found that earlier version of “Classical Gas” and recreated the alternate version of the record.

My understanding is that you made several other subtle changes and tweaks to the original versions of the albums for the reissues.

There were a couple of little things that were done. There were a few places where there had been mixes that were chosen at the time the records came out that were either controversial or were the result of trying to placate a record label concern—in other words, something I didn’t feel right about artistically from day one. In those cases, I exercised my right as the artistic director to say “I’m going to correct something that was wrong from the start.” These things aren’t etched in stone historically and they shouldn’t remain wrong just because they’ve been there for a long time. If it was wrong, it was wrong and I’m going to do the right thing now. There were also a couple of little edits and technical things that I fixed. At the time of the original releases, they sounded as good as we could do with razor blades, editing tape and magnetic tape. But sometimes, things like cross-fades were a little jumpy. Because I had the original elements of the records, I was able to fix those. I didn’t want to go back and completely re-record a song, because they are historical documents that represent a particular time and place. I didn’t want to screw around with that, but if there were contemporaneous corrections that were purely mechanical, I didn’t see any reason not to fix those things.

What’s an example of something a record label made you do that you wanted to change?

On the Games album, for “Delta One,” they favored one mix over another because they felt, of all things, that it was more compatible with the disco era. I never quite heard it myself, but I kind of acquiesced to their A&R people who said “This one will sell a whole lot better.” You really need to have the promotion and A&R team behind you, so at the time, I gritted my teeth and said “Okay, let’s go with your mix.” My mix—the one I preferred—sat on the shelf. For the reissue, I felt the mix they chose had dated very badly. It wasn’t really me. They brought in another engineer to do the mix. It was someone I knew and respected, but he was working in the field of creating singles and had a very different approach. It was very easy for me to put my hands on the other mix because I never let it out of my sight. So, I inserted it back and I think it fits better.

Larry Fast, 1984 | Photo: Bernhard J. Suess

Larry Fast, 1984 | Photo: Bernhard J. Suess

It’s hard to believe there was an era when Synergy singles were getting played on commercial radio.

There were several of them. And different territories would do different things too, like making their own edits. Sometimes the album had something that ran long and the label required something shorter in order for it to get radio play. There was a reasonable amount of radio play in the days of progressive FM—places like WMMR, WMMS and KSHE. There were quite a few regional FM powerhouses that played the records. That’s why the first couple of Synergy albums did very nicely for solo electronic music on the Billboard charts, charting well up in the top-100 of the album charts. The singles were an outgrowth of that. That’s how record labels thought back then. They certainly don’t think that way now in terms of creating an electronic hit that might get airplay. I don’t think they ever fully understood that there was a difference between an electronic hit like “Popcorn” versus what I was doing with the Synergy project, but that wasn’t going to deter them.

As a body of work, what do you believe the Synergy back catalog represents in terms of the evolution of electronic music?

You just hit the nail on the head. The catalog represents snapshots of different points in the evolution of the techniques and technologies that went into making electronic music. The first album was absolutely tedious during the process of making it. It was done one note at a time, with individual patches on 16 track. There were also the difficulties the old Moog synthesizers would present. As the track count went up, it became a little easier to work around some of that, but with 16 tracks—or at the very beginning with four tracks—it was quite an ordeal to extract satisfying music out of these very tedious techniques, but in the end it was worth it. As the years went on and the instruments became more sophisticated and the recording equipment became more capable, the process became interesting, from my perspective.

The voice that I had for the Synergy productions didn’t change that much over the years. The sophistication might have got a little more polished, but the overall sound spectrum—the widescreen, orchestral approach—didn’t change that much, no matter if it was created on the earliest analog synthesizer or the computer-oriented, digitally recorded and produced methods I use now. To a person that’s not well-versed in the technique of how it comes together, everything sounds related. It’s not as though it’s a different artist. So, that was an interesting continuity that came through. Yet, behind the scenes, in terms of composition and recording techniques, it got easier. The nearest analogy that comes to mind is the way an author scratches out something in pencil on a legal pad, trying to refine something he’s writing, versus working with a word processor and cutting-and-pasting, moving things around and wholesale deleting. Conceptually, it’s similar to computer-assisted composition. It’s not the computer doing the writing, but the computer acts as a very flexible tool that makes me be a better composer. It really helps lessen the amount of work and fatigue factor.

Do you ever get nostalgic for the old days?

To be honest, not that much. I can always play one note at a time on a 128-voice synthesizer if I choose. [laughs] I can set up a little mental roadblock and say I’m only going to record on eight tracks, even though I have more than 100 available on the computer. The only thing I get nostalgic for is the social environment. It was different being in the recording studios. The whole nature of that scene has evolved and changed significantly over the past 30 years, but that’s more yearning for my youth than anything else. [laughs] I like the new technologies. If there are things wrong with them, there are usually workarounds. The old technologies are still great and have their place. There are some people who still swear by them. But I was always chafing against the limitations of the older machines, waiting to live in the future that we live in now.

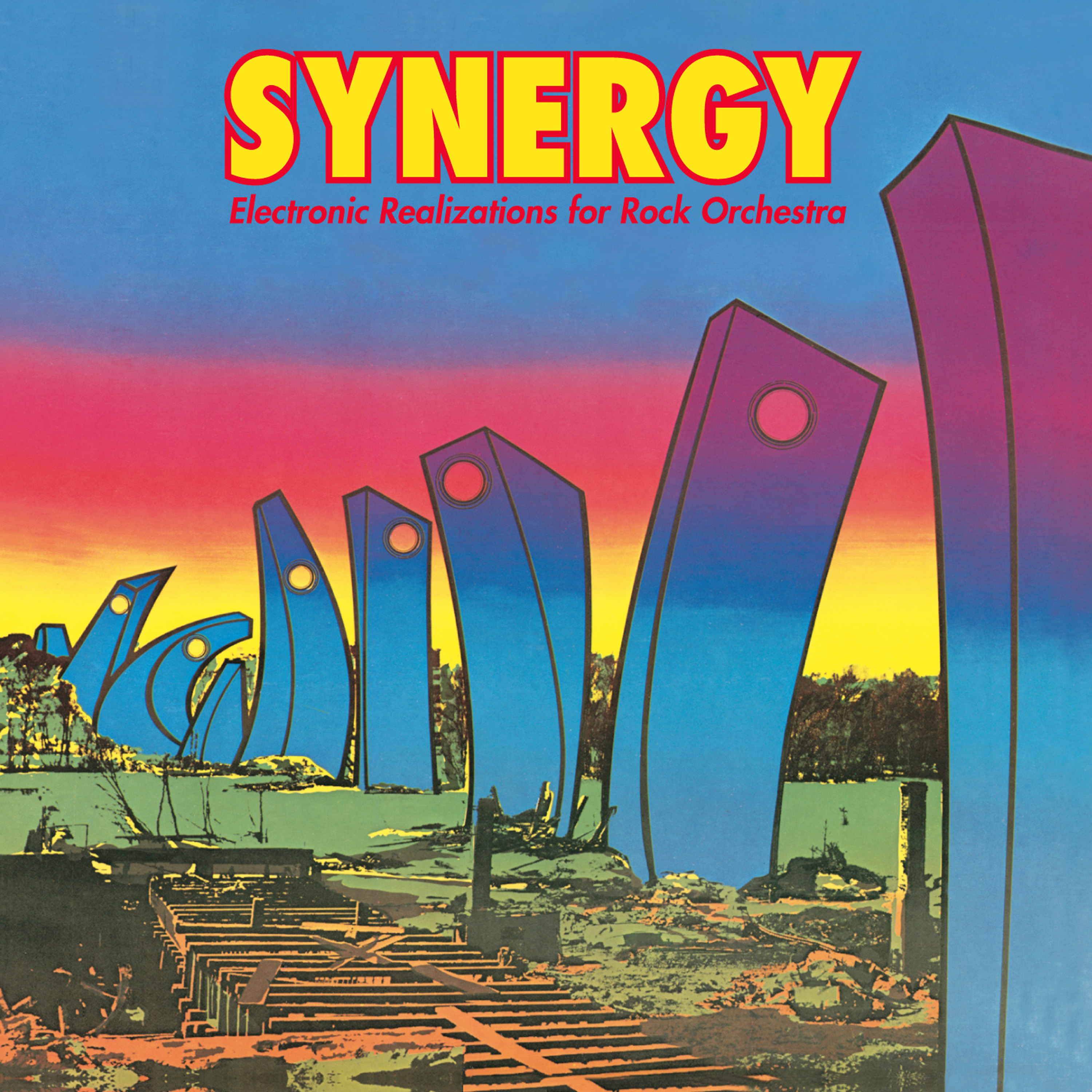

Let's go through several key Synergy albums and have you tell me whatever first comes to mind. First up is Electronic Realizations for Rock Orchestra. (1975)

It was the first one, so there was a lot of learning to be done over the course of recording it. There was learning everything from the record industry itself, because there’s more to it than just creating music. You learn the ropes in terms of what the promotion and A&R people do. It was an exciting time, just getting the feel. I knew a bit about it, but I was learning even more from the inside, being a recording artist for the first time. I was fairly well-prepared for the record. I had recorded the entire album to four-track in a kind of sketch form and it sounded somewhat like what the final record ended up sounding like. I had it plotted it out like an Alfred Hitchcock movie. I knew every scene and had every patch notated ahead of time, so it was just a matter of going to the studio and executing it under much better recording conditions. In spite of thinking I had everything under control, there were always surprises that popped up in the way the recording was coming together that required some thinking on the fly. Sometimes new technology would become available while recording that would change things. For instance, the studio acquired one of the early digital delay mics, so I didn’t have to use tape echo. That opened up another set of possibilities I hadn’t counted on during the original demo versions.

Let’s move on to Cords. (1978)

Cords was unique because it had a guitar synthesizer and also because Pete Sobel, a very good guitarist and an old acquaintance I had been in a band with, was involved in creating it. So, I wasn’t operating so much in a vacuum. I had somebody to bounce ideas off of and share some of the burden of engineering and other technical aspects of making the record. I think every Synergy album is different for different reasons. In that case, another difference was there were people from the record company there as executive producers, putting in their two cents. They weren’t musicians in the way Pete was, so I tended to pick and choose a little differently amongst the ideas the record company was throwing at me, whereas when you’re working with someone who is a valued and trusted partner, it’s a different set of creative interactions and experiences.

It’s very interesting to hear you talk about the input of the record label. The thought had never crossed my mind that they would be involved in tinkering with your output as they would with a typical rock or pop artist.

It was a matter of fighting for my vision. I have to admit that compared to the kinds of pressures that rock bands were getting, I almost had a free ride. [laughs] But I wasn’t completely free. There was still that tint and it got better and less and less pervasive as my career moved on. But for the first five albums, they were looking over my shoulder because they were investing promotional dollars, pressing up the records and getting them into their pipeline. They wanted to make sure they had something they felt they could work with. They didn’t know if they could trust this new kid with his Moog synthesizers to give them what they wanted entirely. They weren’t completely untrusting, but they weren’t going to turn me loose with the money they had allocated to distributing these records. They weren’t going to let me hand in just anything at that point.

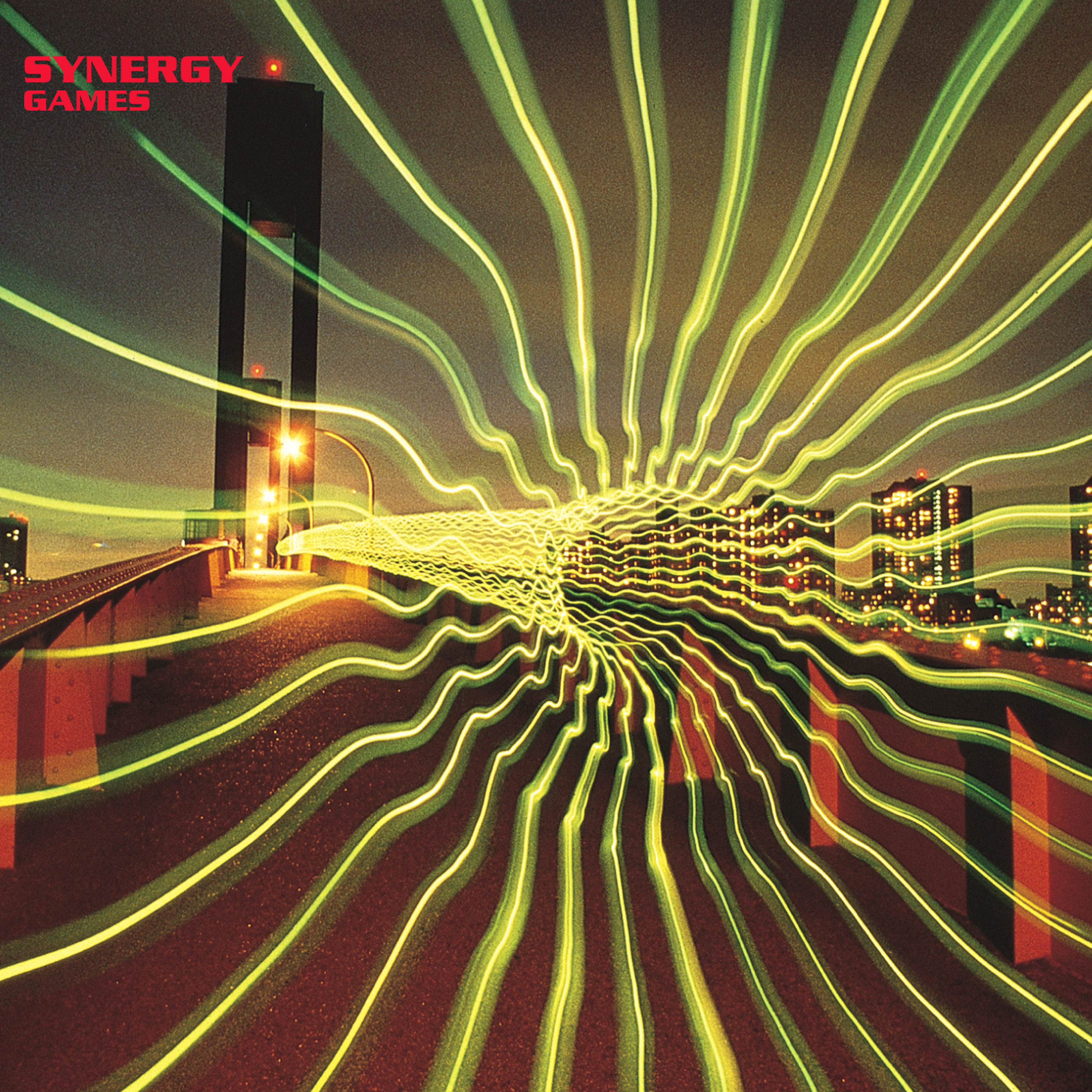

How do you look back at Games? (1979)

Games was the first encounter on a Synergy album with digital synthesis and to some degree, digital recording. It was done under laboratory conditions at Bell Labs, which was then the crown jewel of the AT&T Research Lab. It’s still there, but it’s now part of the crown jewels of Lucent. AT&T was the telephone company—Ma Bell—back then and had lots of wonderful “blue sky” research going on in computers, audio and various other technologies. They would fund these things thinking—and rightfully so—that at some point, something would surface out of these free thinking projects that might be beneficial to the phone company. They don’t do that so much anymore. At that time, there wasn’t any real competition in the phone business. Now, it’s very cutthroat. However, at that time, one of their great, shining lights was Max Matthews, one of the pioneers of computer music and electronic music, at the academic and theoretical level. One of his departments was speech and synthesis. They were exploring several areas of synthesizers, speech and vocals, which could be made into singing. He had worked on one project as early as 1976 that incorporated aspects of that.

By 1978, they had some of the very earliest digital synthesizers, running essentially as software, with some concurrent specialized hardware they had built on minicomputers. They were just mind-boggling to me after struggling to extract sounds from the Moog, Oberheim and related instruments I had been working with in the analog world. This was positively world changing. Again, like any technology at the beginning, it was a little tedious and difficult to control. I was just getting my feet wet, but there were a few passages recorded at Bell Labs that found their way onto the Games record. The passages were enhanced with some of the analog synthesizers to flesh out the arrangements. It was a very eye opening experience. It set part of the tone for the album. The other aspect of Games it that I was on the road a lot with the Peter Gabriel band and recording with them as well. It meant that some of the writing was done on the road, captured on small cassette recorders and lots of scribbled-down notes. It was the first album where I hadn’t set aside a block of time in my composer’s studio to write. It was a different approach.

That brings us to Computer Experiments Volume One. (1981)

That was a combination of creativity and hardware. It was also the first foray into using computers—small computers or microcomputers that were evolving into the kind of desktop home computers that are so pervasive in our culture now. They were just at the beginning right then. The story behind the way that album came together relates to John Simonton, a friend of mine who still owns and runs a small synthesizer company in Oklahoma City called Paia. They were creating synthesizer kits and started building some of the first small computers designed to become part of an electronic musician’s arsenal. John wrote a program called Pink Tunes and it was based on controlled randomness. It was a nice blend between letting the composer set the parameters and then turning the computer loose to mix, match and play with those parameters and run the synthesizers to create different types of melodic structures and interactions.

John’s original program was geared for running the analog synthesizers his company was building, but I had the first generation of Prophet-5 synthesizers which was a hybrid between a microcomputer-controlled polyphonic synthesizer and the Moog equipment in terms of capability and sound. I developed a hardware hack in which I could reach a certain port on the Prophet-5 controller computer and tie that directly to John’s software running on his company’s little computer and run Pink Tunes. I made a few little tweaks to his software too. So, it was a different approach from the arranged, composed type of Synergy recordings. It was a kind of ambient and atmospheric record. I was always looking for the right way to express that type of computer composition. I named it Volume One because I fully intend to have another volume someday. So far, I haven’t come across the right software package that does something I’m pleased enough with.

Given the meddling from the record label you were experiencing, how did you get such an uncommercial record past the goalposts?

That was interesting. As with most things in the record business, it came down to money. That record was incredibly cheap to produce because I could do it at home. My home studio capabilities had expanded pretty significantly between 1974, when I first started recording for the label and 1980 when that record happened. I wasn’t going into it with the idea of making a record either. I was approaching it as an experiment in computer composition and what could be done by bringing more and more computer control into the composing aspect. Then I completed the recording but wasn’t sure if the label would be interested in releasing it. But what happened was that at the same period, I was working on the Audion recording, the next album with the familiar composed, arranged Synergy approach, which at the time, I felt was my best one to date. The label was looking for some interesting ways they might set this one apart. They were aware that I had created Computer Experiments and came up with the idea of releasing it as a mail order-only LP available via an insert that was going to go into the Audion LP. That’s precisely what they did. The first 5,000 copies were only sold that way, individually numbered. It did well enough that within a couple of years, they decided to put it into general release without the special packaging.

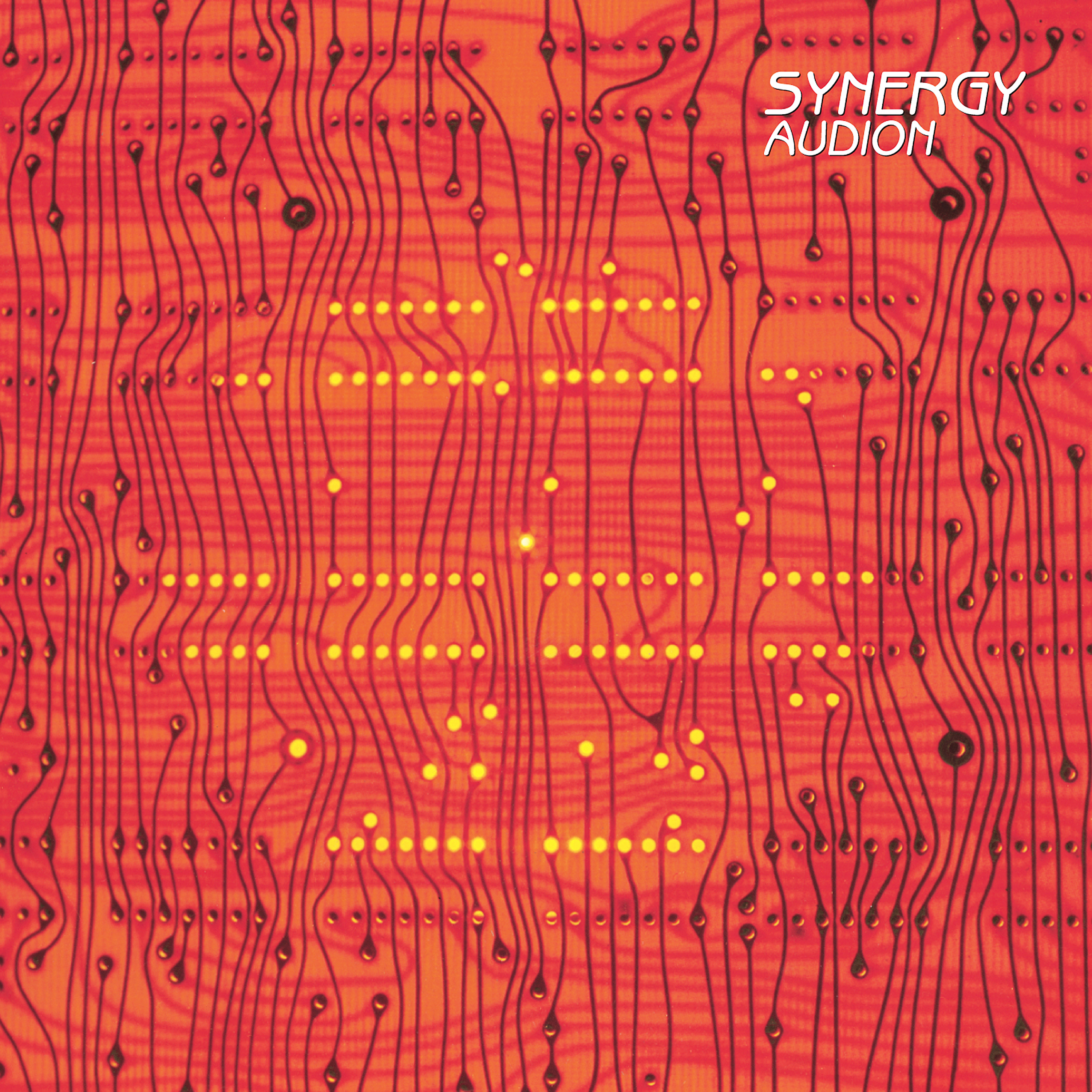

Audion (1981) is up next.

Audion was what the label was expecting as the next Synergy project. It’s also when record company input was largely fading away. By the time I was doing Audion, I wasn’t submitting every reference mix of every track to be vetted by the people in the A&R division. I used to do that a lot in the early days. I would get lists of comments on things that ought to be changed from people at the label who would visit the studio. By Audion, I was still sending reference mixes, but there was virtually nothing coming back in terms of comments or suggestions except “That sounds good. Finish it up please.” [laughs]

With Audion, the equipment was getting even more sophisticated and it was enabling me to approach the more complex tonal and sonic spectrum. It allowed me to explore some of the sonic textures with more subtlety and detail. I was a little bit regretful at the time that the connection with Bell Labs ended as I was starting Audion, so I didn’t have access to that environment anymore. It was still too early for non-laboratory digital synthesizers. The Fairlight CMI and Synclavier were just beginning to emerge, but I didn’t have access to the prototypes or early models at that point. So, for Audion, it was a matter of backtracking a little bit to all analog synthesis, but there was a little more computer control available. I was able to augment the analog recording with outboard gear, different flangers and phasers, and digital reverbs. A lot of the equipment was at a higher level of sophistication and I think the mix shows a wider sweep and bigger dynamic range. Things were getting more punchy and aggressive in terms of what the sonics could do. I’d also like to think my level of sophistication as a composer was evolving. Hopefully it will not stop evolving. Audion seemed to embody everything that happened to that point.

Many consider the next album, Metropolitan Suite (1987), to be your masterpiece.

There was a gap between Audion and Metropolitan Suite. I had done soundtrack work for The Jupiter Menace, which involved some licensed reuse of earlier Synergy tracks. There was a whole lot of new music done for the film too. Then a long, extensive Peter Gabriel tour followed. After that, I created the Semiconductor compilation that had a couple of new pieces on it. That took things up to late ’84. I was also doing a lot of studio production work for different artists from the early '80s on. Aside from Peter Gabriel, I worked with Foreigner, Hall and Oates, Bonnie Tyler and Jim Steinman on a lot of his projects. The first gap came in 1986, about 24 months after Semiconductor was done and that’s when I got back to work on what became Metropolitan Suite.

There were a couple of big jumps on that album. It was the first Synergy project where the recording wasn’t done straight to tape. It was first composed on MIDI sequencers and I was able to polish the composition a bit more. It was also the first Synergy album to have digital synthesizers outside of the original Bell Labs work I had done. So, there were elements of sampling, digital FM synthesizers and other things going on. It was still hybridized in that it still had the Moog modular with all the patch cords and instruments like the Prophet 5 and Memory Moog. It was also recorded to digital tape, not analog tape. So, that foreshadowed what was going to happen in the recording world at large, not just for electronic music albums. As far as writing, it’s fairly obvious from the suite itself that I was in my Gershwin phase. I was really studying Gershwin’s orchestral works such as “An American in Paris” and “Rhapsody in Blue” and just picking up the core, essential ideas. What I liked about what Gershwin was doing I tried to pull into my own world. I was working on a lot of top-10 pop records at the time, but still longing to explore the orchestral side of my own compositions. Gershwin was someone who made his reputation as a Broadway composer and a pop writer. He then became a very respected composer of serious American music. I thought the parallels were somewhat similar and in studying him, it naturally rubbed off on my own composition of the suite.

That brings us to Reconstructed Artifacts. (2002)

The accidental album. [laughs] From the earliest days of my career, I begged off on live performance. It just wasn’t possible to take the early Moog synthesizer albums, done in the tedious one-note-at-a-time manner, and turn that into a live performance. Live performance with synthesizers at the time was something entirely different. It was fabulous soloists in the progressive rock era like Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson doing what they do very well with single line soloing, but not in an orchestrated approach. That simply wasn’t what I was doing. My work was more in line with the work of my friend Wendy Carlos or Tomita. They were inherently studio projects.

In the mid-‘90s, Wendy Carlos was approached to do Switched on Bach live. In 1968, that was a ludicrous request. It would have been impossible. But by the mid-‘90s, Wendy realized that as complex as what she was doing was, it could be performed in real time by eight players with sophisticated, digital synthesizers—Kurzweils, in particular. She gathered seven of her musical friends and I was flattered to be one of them. We became the Switched on Bach ensemble and performed as part of a Bach festival. It worked very well. I realized the equipment had finally reached a level of sophistication that allowed these seemingly impossible pieces from the '60s, '70s and '80s to be pulled off live.

The next step in the evolution was when Tony Levin gathered up some of us from the Peter Gabriel band in the '70s and '80s to become the Tony Levin Band. During the first tour in 2000, we were each given the opportunity to do a solo spot. I realized that with the Kurzweil synthesizer and some assistance from the sequencer inside it, I could perform some of the Synergy material. The sequencer plays some of the parts, leaving the fun stuff for me to perform in real time. I chose “Flight of the Looking Glass,” one of the shorter pieces on Audion. For the next Tony Levin Band tour, we performed “Phobos and Deimos” from Cords. I had a lot on my plate to pull that off live. I had a lot of assistance from the other three guys, but the core of the electronics was still falling on me. However, it was getting more and more manageable to do it.

Next, I was approached by the Alfa Centauri electronic festival people in Holland to see if I’d perform at the 2002 festival. They were very persistent and it was very flattering. I had turned them down before, but this time, they pointed out to me that they had evidentiary proof from the Tony Levin Band performances that I could perform live. Finally, I acquiesced and then realized I had a monumental task ahead of me. I had to go back and recreate all of the patches that had been constructed on the Moog synthesizer going back to 1974. So, I created my own backing tracks using authentically-patched sounds. As I was putting all of this together in the sequencer on the Mac using Digital Performer to virtually recreate the multi-track performances that had made the original recordings, it dawned on me two-thirds of the way through that I’ve got new, digital versions of all of these songs available. If I played the parts into the sequencers and control the mix, I’ve created recreations of the older pieces and that’s exactly what happened.

When the festival was about to happen, I realized it would be good to have something special for the fans to commemorate the show. I did a private pressing of the new mixes of the old songs, but with all new recordings and patches. I tried to recreate the same kind of authentic feel from the analog synthesizers and it came out great. The performance went off wonderfully and the fans in the audience snapped up copies from this private pressing. I had a second run done and we brought them on the Tony Levin Band tour we did during 2002 and they sold very well to the Synergy fans that were coming out. So, when the new deal with Voiceprint was coming together, they said “Why don’t we put that out as a regular release?” So, I did.

Does it ever get challenging to maintain your enthusiasm for the older Synergy material?

I thought it would be, but maybe I’m just too much of an egotist. [laughs] In fact, I surprise myself and think “Geez, I was 22 when I wrote that? How did I do that?” And then I scare myself because I wonder if I could do it again. I’ve talked to other composers about that. We generally have the same reaction to our own older works. I don’t think I’ve been forced to be exposed to the material on a constant basis, so when the CDs were first remastered in the '90s, I got to immerse myself in them after not focusing on them for quite a while. It was a pleasant experience. Going into it, I was worried it would become tedious and maybe a little embarrassing in that perhaps things had dated badly. That wasn’t the case, thankfully. The fortunate thing with the Voiceprint releases is that for the most part, the remastering done in the late '90s is completely up to early 21st Century standards, so I didn’t have to reinvent the wheel. It was just a matter of finding the extra material and doing the inserts.

Larry Fast, 1987 | Photo: Miguel Pagliere

Larry Fast, 1987 | Photo: Miguel Pagliere

You’ve been busy on many projects since Metropolitan Suite, but one has to ask why recording an album of new Synergy compositions hasn’t been a priority.

It comes down to time and perhaps that I’m a pushover when it comes to other people asking me to do things, rather than saying “No, I’m not doing your project. I’m doing one of my own.” I’ve been working on projects like one I did for Disney, in which I was commissioned along with several other composers, including Tomita, to do new compositions for their theme parks in Tokyo, which opened a few years ago. It was a very extensive project. By the time I was done, I created three hours of new mixes. Some of them were variations on the same recordings, but it was the equivalent of two-and-a-half albums. So, that drained me as a composer. That was interspersed with working on projects for XM Satellite radio, as well as the Tony Levin Band albums. We were nominated for the 2003 Grammys and that kept us pretty busy. When I’ve done Synergy albums in the past, I like having a clear block of time in which I don’t have anything else that’s interfering. That’s been difficult to come by in recent years.

It’s going to get a little bit easier soon, but there are some impediments. We’re going into a big building construction project for my house, which will result in a new studio. This is a good thing. But I won’t have a new space until it’s done and that won’t be for awhile. That will go through the rest of the year. Life is complicated. The Synergy projects are enormously gratifying, but sometimes the other projects have managed to take precedence.

Is working in surround sound appealing to you for future Synergy projects?

Absolutely. If you put on the first Synergy album, it still is in surround. I came in at the end of the quad era. So, the first one is done in quad, which is effectively Dolby Pro Logic. If you put it through an analog Pro Logic or Pro Logic 2 decoder, it comes back and it’s actually much better than it was on the LP. I enjoyed that thoroughly, but by the time I got to Sequencer, that whole era of quad mixing was fading away. I’d absolutely like to go back and at least take Reconstructed Artifacts and mix it in surround. Since they are newly-created masters and I have 5.1 mixing capabilities in my studio, that’s something that can be done.

How do you look back at the making of the third and fourth Peter Gabriel albums?

I look at the third album as the breakthrough in which Peter really got to do what he had been talking about from before the first album. It has a kind of directness. The first two albums with the producers Bob Ezrin and Robert Fripp had to be gotten through in a sense, but by the third album, Peter was ready to launch out of the gate. A lot of the techniques and approaches on the third album involved a certain self-limiting factor because Peter wasn’t that successful yet. He hadn’t had the number one records yet, so it constrained the third album, but not in a bad way. It reached the right point which made it into an absolute classic. The fourth album was the third album with no restraints on it. So, it went on and on for months and months and things never got finished the way they maybe should have. There was more money for toys and tech tools. Sometimes, too much of something in that field can actually be detrimental because it can get in the way of creativity. I don’t think the fourth album was a failure—far from it—but I don’t think it has the incisive focus on its goal that the third album had.

With the third album, it’s tough to beat it. No matter how much time, money and new equipment you throw at it, it would be hard to top. During the production of the third album, the motto we had on the wall read “No middle ground.” So, everything either had to be starkly there or not there. The sound had to be the most edgy, in-your-face sound in the world or it had to be the most subtle. If you heard the rhythm tracks on the album, it sounds like a fairly conventional record. A lot of what made it special was actually by removing, not adding. Occasionally something would be added for punctuation and subtlety, but the album is very sparse. That means what remains is very upfront and becomes very important in creating the atmosphere of the record. The fourth album didn’t quite maintain that level of work ethic. It became a little more conventional in that sense.

Larry Fast on tour with Peter Gabriel, 1977 | Photo: Brad Owen

Larry Fast on tour with Peter Gabriel, 1977 | Photo: Brad Owen

Are you still in touch with Gabriel?

Peter and I are still quite cordial. We still exchange emails and I helped get things together for the programming on the current tour. They’re doing “San Jacinto” and I was the only one that had all the archival material and Fairlight sequences. I gave all of that to Peter and Rachel Z with very detailed instructions on how to make it happen. I hope they read all the details and are playing it very well.

Is it strange for you to see Gabriel perform live these days given your previous involvement in the band?

It was only back in the '80s. So much time has passed and we’re all good friends. I’m almost disconnected from it. That’s why if they need my help in pulling something together that I had a heavy contribution to, I say more power to them. Talking to my friends in the live theater world, it’s like people taking over a role they were in when they went on to something else.

What do you recall about working with Kate Bush on her Never For Ever album?

I got to know Kate through Peter Gabriel. Kate had come in and done vocals for some of his projects I had been involved in. She’s a lovely individual and asked if I could bring my synthesizers and do some of the things I brought to Peter’s music to hers. It was a thrill for an entirely different reason in that she was recording in Studio 2 at Abbey Road, which was the Beatles’ studio. Not much had changed in the studio since the last years of the Beatles. So, for a die-hard Beatles freak like me, to be sitting right there at the power center was really wonderful. On top of that, Kate’s music was really great, so it was a thoroughly enjoyable experience. I didn’t work with her for that long. Working with Peter would take months and months and months of work, but with Kate, it was a few days. My contributions weren’t that complex. She asked for a bit of electronic orchestration and not terribly difficult synthesizer parts. She is a very bright lady and knew what she wanted. I could have made suggestions, but she had particular things she wanted done and I have to say they were absolutely right for her music.

What can you tell me about your time working with Rick Wakeman in the early '70s?

I worked on hardware for him. I was doing electronic music before recording professionally and I wasn’t very set financially. The Moog equipment was phenomenally expensive back then, even in today’s dollars. I had a good background in electronics, so I was designing custom modules for myself. I first encountered Rick through my early work in college radio when Yes was first starting out. They were still traveling around in a station wagon and doing tiny, little concerts. I spoke to Rick literally a couple of months after he joined the band and we naturally touched on electronics and when I described some of the things I built for myself, he said “I’d like to have those for myself. Would you build some of those for me?” And in fact, he had the road manager give me the deposit that night. About six or seven months later, I delivered a finished, custom sound synthesizer module to him which he ended up using on the Yessongs live album. The first time I heard myself on the radio in a sense was hearing him use those modules on that album.

He suggested I come to the studio when the band was recording Tales From Topographic Oceans to see how the device was working and offer some tips and techniques, as well as do a little upgrading. So, I went to England for that, among other things. It was a very good opportunity. I was able to spend a lot of time in the control room watching Eddie Offord work. I learned a lot about the techniques that were important to the way British albums of the time were engineered. It was quite different from the way American recording was done in the studios in the New York area. I brought a lot of those techniques back with me and they have stayed with me. So, whether I was working with Peter Gabriel, Nektar, Kate Bush or acts in America that had British roots like Foreigner or Bonnie Tyler, I always had a cross-Atlantic thing to offer.

Larry Fast, 1978 | Photo: Jonathan Sievert

Larry Fast, 1978 | Photo: Jonathan Sievert

What was it like to be around Yes in the studio?

It was eye-opening to see. They had become quite successful, but I was fortunate to first get to know them before the great success had hit. It was nice to see them have that success. It was interesting to see that whether I was working in my local band of non-professionals or with this top of the heap, very talented and successful band, the same little squabbles and disagreements would break out. It wasn’t all that different. [laughs]

Recent times have seen you work with Nektar again. What piqued your interest in the reunion?

Part of it was like going back for a high school or college reunion. It’s fascinating to think that after all these years, it could happen again. I’ve been socially connected with most of the Nektar guys that stayed in the States. The band is made up of British citizens that made the same pilgrimage to Germany the Beatles did. It was a rite of passage for bands in the '60s. You’d go to Germany to become more successful and triumphantly return to the U.K., but in Nektar’s case, they stayed in Germany. They became very successful there, largely married German women, had kids there and spent the latter part of the '60s through the mid-'70s in the country. Later, in the mid-to-late '70s when they became more successful in the USA, they came over. Things didn’t quite play out as they hoped. They were successful for awhile and then the success started to wane.

There were some internal factors—the kinds of things that happen to many bands that have been together awhile. Most of the band members chose to remain in the USA, but the principle guitarist and vocalist Roye Albrighton decided he wanted to go back to the U.K. and that fractured things and it ended. I stayed in touch with the American contingent that remained and the idea of the whole thing coming back together sounded like too much fun to pass up and it came together quite well. The interesting thing was that I had been continuously working in the music business and had a couple of years of recent touring under my belt. The others hadn’t been on a stage in that way in many years. So, where I was the new guy learning from them in the ‘70s, I was the one coming back with the success of the Peter Gabriel years and the recent touring. I was able to help bring a certain level of early 21st Century performance to the situation. Listening to the tapes of the first reunion performance at Nearfest in 2002, I thought they were better than anything I heard of the tapes from when I was performing with them in the mid-‘70s.

Are you maintaining an ongoing relationship with the band?

To the degree I can help out, yes. There’s a core group that doesn’t include the original members that has been touring Europe. They’re getting a good response, but it’s in rather small venues. They want to tour extensively and my obligations to the Tony Levin Band, XM Radio and other projects prevent me from participating in that.

Between protecting the Synergy name and your recent foray into digital watermarking, it's clear you take intellectual property very seriously.

I think most creators do. There’s a certain possessiveness you feel about your baby. The environment is constantly undergoing change. I think those that create music, whether there’s a lot of money involved or not, like to be compensated for what they do instead of pressing up CDs and giving them out on a street corner. It’s the same thing when it comes to file sharing and downloading, though I don’t think the heavy-handed approaches to preventing that are appropriate. When I got involved in watermarking, it wasn’t as an anti-piracy device, but as a new way to track usage.

When music is played on terrestrial radio, ASCAP and BMI track it and eventually get some payments back to the creator or publishers. With computer distribution, some kind of new paradigm was going to happen and I thought watermarking was probably a good way to keep track of things, so that something like a search engine could find out where your music is. If it’s just somebody sending a copy to a friend, it could choose to ignore it. But if it was someone email blasting thousands of copies of it or if it was up on a server for the taking, that server could become like a radio station and pay a little blanket license of some sort. Watermarking seemed at the time to be an essential tool for making that feasible. It didn’t work out. The people behind the watermarking—not the technology people, but the corporate backers—really thought it was a way to put these heavy-handed locks on what could be copied and what couldn’t. Because of that, it never happened. I not so much backed away from it, but it ran away from me, so I don’t have any involvement now.

My interest, aside from intellectual property, was to see if a system could go in place that was sonically pure and crystalline that doesn’t interfere with anything us producers were doing. The early systems did meet those requirements. It’s a dead issue at this point, but the overall philosophy was to ensure creators get compensated. I think there’s a lot of greedy hands out there. Conventional radio grew up over many decades of figuring out how to make the system work to its advantage. I don’t think it was any fairer to the artists than when music is just freely distributed without compensation. I don’t have any blanket solutions, but I think the creators, composers and performing artists are still at the center of what’s important. If all incentive goes away, people aren’t going to be doing it as much. I already know many talented musicians who should have been heard but never were and their careers have gone into decline while they went into other fields to feed their families.

What do you think about the record industry perspective that says it’s not greedy but the individual consumers are?

If something’s free, people are going to go for it. It’s human nature. If you have an enormous amount of power like the major labels had until fairly recently, they’re going to use it to extract the most money from people making creative product for them. So, they’re greedy. The people that would rather steal music, in the most negative sense, are greedy too. On the other hand, there is a certain level of interested people who are doing some file swapping, which is now the 21st Century equivalent of hearing stuff on the radio. So, it’s a very fine line to figure out how to be a creative artist and have a career, yet not be so greedy that you’re cutting yourself off from the people that really want to hear what you’re doing and will somehow support your music.

Do you feel you've received your due for your influence on electronic music?

Probably. I know that within the community of electronic musicians, at least those from the earlier days, there seems to be a flattering level of respect. I see that when I’m on panels at audio and music conferences. So, I feel good about that. I think time is moving on and there are histories of electronic music that completely write off anything that happened before techno. So, electronic music has come to mean something entirely different. In most fields, there is a tendency to forget anything that happened before the very recent past. It’s just accepted that of course, there were always synthesizers. There isn’t a lot of thought about where they came from and who created the early works that were significant. I’ve remained visible to a large degree, particularly in the rock and pop world, so I’m doing okay. I’m very worried that Wendy Carlos, who really invented a lot of what those of us doing electronic music worked towards, is getting written out of the collective history.

Larry Fast, 1975 | Photo: R.A. ErdmannHas anyone sought permission to remix Synergy tracks?

Larry Fast, 1975 | Photo: R.A. ErdmannHas anyone sought permission to remix Synergy tracks?

It hasn’t happened yet. If it did, I’d go for it. I’ve licensed things for hip-hop tracks where they’ve taken loops out of Synergy records. To be honest, I’m not that familiar with the artists. Rick Rubin produced something with Saul Williams that did quite well. They’re nice. I always make sure I understand how the music is used. Even though I don’t think of myself in political terms, I do want to hear what the lyrics are about. If it’s something I really can’t get behind at all, then I would deny its use. That hasn’t happened yet. Typically, with all of these, they’ve come to me after the track has been recorded and gone “Oops. We want to license this.”

What other artists have used Synergy samples?

Chromatic and Pharcyde are two others. There are also things that I found out about years after it was too late to do anything—like Future Sound of London took a minute or two of the intro to Audion, looped it, put their own beat under it and called it their own. They are still intact, but it was 10 years ago when the track was done and apparently the international statute of limitations on that thing ran out.

What are some of the other current projects you’re working on?

One of the projects relates to the same design engineering side of me that got me started with Rick Wakeman 30 years ago. I’m involved in designing assisted listening devices for the hearing disabled. I got into that through my wife who has been working in that field for a number of years. I ended up designing and getting granted several patents for optical distribution using infrared audio technologies. So, I’m working on redesigning some digital signal processing to enhance what’s been done for that area. It’s a very gratifying thing to work for people who have hearing disabilities and create technologies that actually have a beneficial use. It’s really nice doing entertainment, writing music and bringing a smile to people’s faces, but it’s even cooler bringing technology to people so their everyday lives have a richness.

Something else I’m involved in is historic preservation. I’m part of a government organization that protects historic assets in my area of New Jersey against developers. It’s mostly architectural structures of significance that are either related to the invention of the telegraph or development of the Arts and Crafts movement in architecture. I’m on one of the regional commissions that grants money for preservation and guides development around the structures. I actually have a degree in history. That, architecture and technology have all melded into one thing for me. The cover of Reconstructed Artifacts has a photo of a meter which is from my collection. It’s from the Edison storage battery company and it’s an actual 19th Century battery meter that was restored and altered in Photoshop. The actual artifact is almost exactly as it was originally manufactured, but the image shows a version with LEDs which wouldn’t have been available in 1896.

I also always want to hang out that little carrot of new Synergy music. I don’t know when, but I’m collecting more and more material. It’s the kind of thing where you nurture it and get ready for a growth spurt and then you harvest it. I can tell I’m moving closer to that.