Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

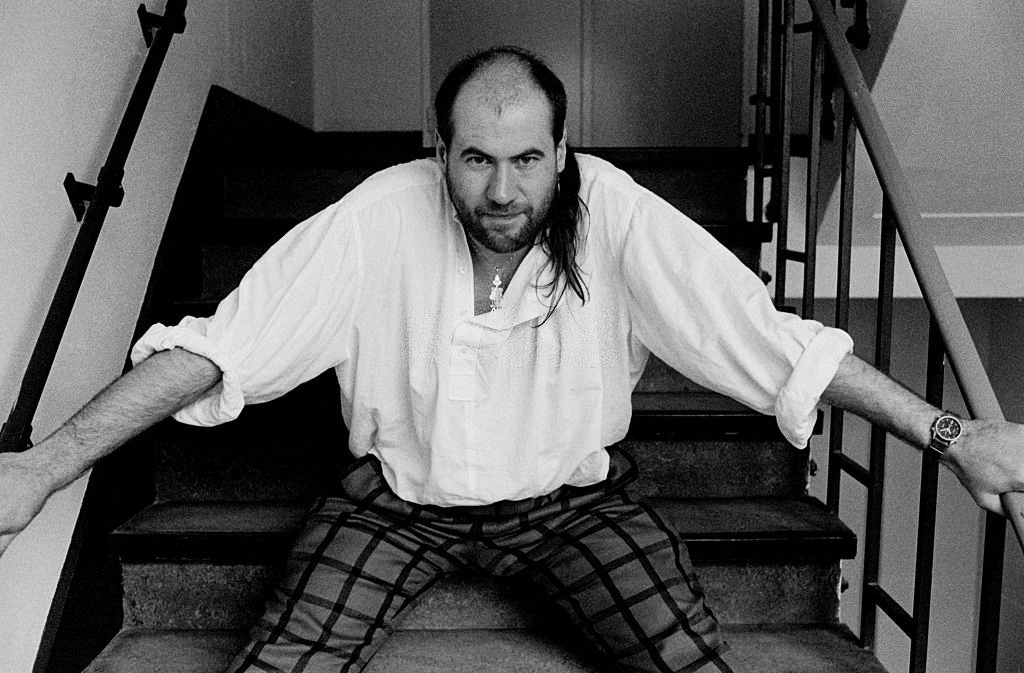

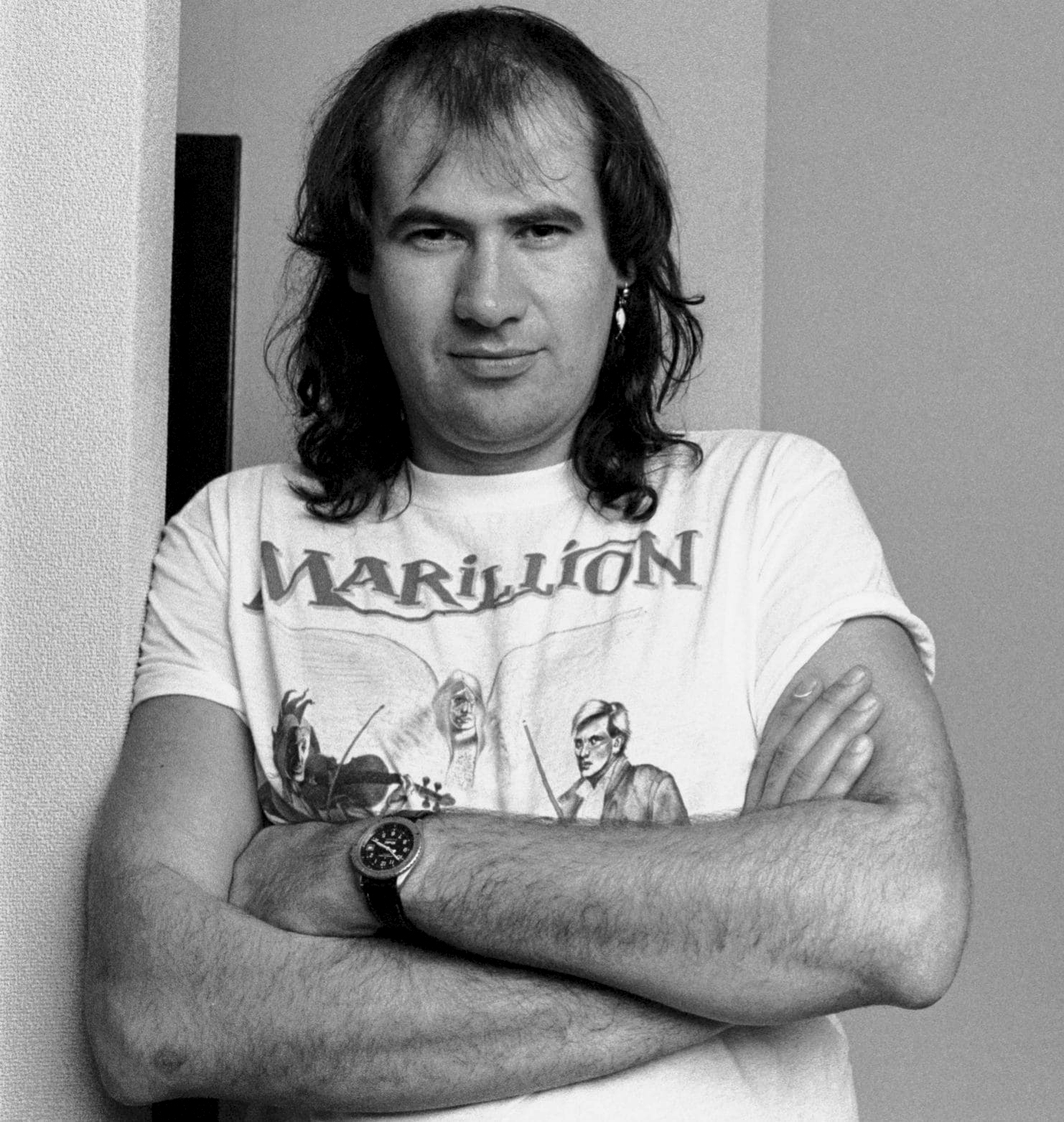

Fish

Mirroring Influences

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1993 Anil Prasad.

Photo: EMI

Photo: EMI

When people think of the neo-progressive rock movement, the first name that usually pops into their heads is Marillion. Throughout the '80s, the British act carried the prog torch for a new generation by combining the art-rock approach of '70's-era Genesis and Yes with more grounded lyrics and contemporary musical influences.

Original vocalist and lyricist Fish, a Scotsman whose real name is Derek Dick, helped lead the group to incredible heights. Worldwide hit singles including "Kayleigh," "Incommunicado" and "Warm Wet Circles," as well as best-selling albums like 1983's Script For A Jester’s Tear and 1985's Misplaced Childhood established the group as a force in expansive rock circles.

Fish left Marillion in 1988 and since the split, he’s gone on to establish a burgeoning solo career. It’s one that’s seen him move further and further away from prog-rock and into the fields of contemporary pop and traditional folk. But he hasn't forgotten his roots. Most of his albums include at least a nod back to the intricate, instrumental grandeur of his Marillion days.

The following is the first post-Marillion Fish interview given to North American media. In it, Fish discusses a variety of burning issues, including why he left Marillion, the state of his solo career, bootlegging and Scottish nationalism. It’s also an in-depth look at why he chose to release Songs From The Mirror, a 1993 collection of cover songs originally performed by his musical heroes.

Why do an album of covers at this point in your career?

Because Internal Exile, my second solo album, was done in November of ‘91 and it was pretty much written, delivered and released within the space of two months. It was a fast one. And then we went out on tour for two or three months, then we came back when the recession hit in Europe. Promoters get very nervous and touring gets very difficult at that particular time. There were tours going down all over the place. I didn’t want to risk going out on a tour and having a lot of dates locked in, then suddenly everybody’s getting nervous about it. So we came off, and I went away on holiday, and it was when I came back, the record company was on the phone wondering where the next album is. Internal Exile didn’t set the world on fire in Europe. I mean, it wasn’t a burning bush or a tablet from the mountain. I mean, it didn’t perform at all, which we just took on the chin. Again, I had problems with the record company here, and perhaps the promotion didn’t really lock in. A lot of it had to do with the timing. The album came out so fast. But I don’t think the army was completely lined up – there were still stragglers and that hit us bad as well.

When they asked me for another album, I knew I wouldn’t get one out for at least another eighteen months, and with the scheme of things and the way that record companies operate, where there are optional releases, we were really looking at April of this year. And I felt to go in right after the Internal Exile project where there is all the flotsam and jetsam and bits of bodies of work laying about, there was a danger of creating this sort of rock and roll Frankenstein of an album. If albums have direction, Internal Exile was a roundabout. It was a watershed album. And Vigil In A Wilderness Of Mirrors, my first solo record, was a hangover from the Marillion days – the Marillion influences on it are probably more obvious than on Internal Exile. After Internal Exile, I had to decide "Do I want to go to the progressive side, the folk-rock side or do I want I want to go to the power-rock side?" There were so many options available, and I just felt that three months after an album was the wrong time to make a decision like that and especially with the material that was still lying about. So I decided to go with a covers album, which was supposed to be out last November, but the record company decided to hold it back because there was so much traffic out there. Therefore, it was released January 18 in Europe. But you know, it was an album I’ve wanted to do ever since I was a kid. It was going to be a full album in ‘85, which was held up due to the success of Misplaced Childhood. And again in ‘88 it was supposed to be part of a bigger work, which was going to be called Geisterfahrer, which was an idea I put forth to Marillion for a major theatrical concept.

Photo: EMI

Photo: EMI

What does "geisterfahrer" mean?

It’s German for "ghost driver." It’s a German social problem. A lot of high falutin’ businessmen who end up worshipping cars, say that the best way to commit suicide is to drive up the autobahn, do a u-turn, and drive against the flow of traffic and into a truck. If you’re driving about in Europe real late at night and you put on the radio, you hear geisterfahrer warnings come out on the radio that say "between junction 3 and 17." So, you pull over to the side, and you see this car going by, and a lot of cops are chasing it. It’s quite a deadly little game. And I wanted to do this album about a guy who went on a journey from the time the car engine turns on. It was going to be a bit like Dickens’ Christmas Carol, which was to take characters like a mechanic or a policeman, or another geisterfahrer that succeeded and maybe they can all sit in the back seat, and you know, they can talk to him, and have this musical discussion about his life. And in between I wanted to cover the radio shorts, where the guy switches on and a cover song comes on that’s relevant to his life, like a narration piece from an analytical sense. But Marillion thought it was a crap idea. To be honest, I think it was too ambitious for that band. I don’t think we had the musical ability to actually cope with it. I mean it was such a wide ranging project, and it’s a project that’s locked in for '94 or ‘95. I mean it is going to happen. The idea is already copyrighted. So Marillion turned that one down. And of course when I went to Polydor, it was 22 months between Vigil and Internal Exile, which was an awfully long time. And a lot of the profile and success that I had gained from the first album and tour, I’d lost through the years – it sort of dissipated. I wanted to come out with some fast albums, and the idea was to come out with Internal Exile, and then the covers album. And we’ve written about 40 minutes of the next album, which has a working title of Suits.

You chose to cover songs by some interesting artists on the new album – Sandy Denny, David Bowie and the Sensational Alex Harvey band, just to name a few.

Wow, you’re the first person who knows that’s a Sandy Denny song. You know, it’s really funny ‘cause I had Alan Freeman on the phone today. He phoned me up to say thanks for the dedication. He was blown away you know? And he was sort of saying as a DJ he’s been working since 1952, he’s 60-years-old this year. And he was the DJ that was most influential to me. I mean, I used to turn on the radio and hear all these new bands. Bands like Pink Floyd and King Crimson and all that stuff. So I decided to dedicate the album to him, because so many of the tracks I covered I first heard on his program. And he phoned me up today and it was the first time I’ve spoken to him since I was 17-years-old. He was just blown away by the dedication. And I was blown away by the fact he called me.

I understand you’re now doing some work with the remaining Alex Harvey band members.

Alex Harvey died quite a number of years ago, but the band’s reformed under the name The Sensational Party Boys. And now, I’ve been fronting them with Dan McCaffrey. The last time I ever saw this band, I was standing among 65,000 people, watching them support The Who, at Parkhead football stadium in Glasgow. It was the first time I ever smoked a joint. It was an outdoor gig, it had lasers and shit like that. And now all of a sudden I’m out there singing "Boston Tea Party" with Ted McEnna. It’s fucking great. Ted McKenna played on two tracks on the Internal Exile album.

You’ve also worked with Steve Howe recently.

I just did a cover version of "Time and a Word" – the Yes number. Steve came up to play on it in December. I’m sitting in the studio, and he’s sitting down doing the warm-ups and he throws in Tales from Topographic Ocean licks. And I’ve got my eyes shut, and I’m going "I don’t fucking believe this. This is Steve Howe in my house playing some bits of Topographic Ocean." It was a little boy’s dream. "Time and a Word" is going to come out on an album in the future. But it’s on a single in Germany right now though – the "Five Years" single, a cover of the David Bowie song.

Is that available in the UK too?

No, it’s not coming out in the UK. You can forget the UK. Forget the fucking UK. In the UK, music is a fashion accessory, darling. Unless you have some wonderful new jazzy clothes, and have wonderful dancing shoes it’s not happening. You know, fuck it. You’re not even a starter. So I mean, the UK is just a fucking joke. You turn on the national radio station, and it’s just dance music. I mean we’re talking a dance version of Gerry Rafferty’s "Baker Street." One of those bands that’s been nominated for best new band of the year by the BPI is a band called Undercover who have never written a song in their life. They just do cover versions. I should be up for best new band. [laughs] There is a big thing about cover versions in this country. I feel quite safe with it, in the fact that I’ve already been involved in writing nine albums. All the bands that I picked to cover were all pre-1975. And it was all songs that I knew as a school kid. These were all songs that switched me on to the magic that is rock music. I was an adolescent going through turbulent emotions and just discovering my dick and discovering women at the same time – and trying to work out how to put the two together. At the time, I was thinking about the meaning of life questions, and the "Does God exist?" questions, all the rest of it. I was thinking "I’m a fucked up human being." And when you’re listening to rock and roll, I think you sense the answers, and you sense the emotions, and there’s an automatic link between the two. Then as you grow older, as more influences come in, your vocabulary increases, and as a human being, you develop your own personality, and your own individuality. The links in the chain are the music as it carries on through the fucking years.

This album is a rebirth for me. I was going back, and rather than being an observer, or listening to these songs, I actually climbed inside them and found the key to the alchemy of it all. And I started to wear the songs like they were my own. And by doing this, it was great for me as a vocalist. I gained so much confidence in my voice by doing these songs, because I wasn’t hiding behind my own lyrics. I wasn’t relying on original material that nobody had heard before, and nobody could compare to anything before. I mean, I was setting myself up for people to go "Well this is how Justin Hayward sang it, this is how Sandy Denny sang it, this is how David Bowie sang it. How does Fish sing it?" And I think we’ve done them as good, and in some cases, I think we’ve done them better. It was such a huge fucking kick to go back through that rebirthing process – rediscovering the magic of why you first get drawn into music in the first place. It was an exhilarating experience.

Marillion, 1983: Pete Trewavas, Mick Pointer, Steve Rothery, Mark Kelly, and Fish | Photo: EMI

Marillion, 1983: Pete Trewavas, Mick Pointer, Steve Rothery, Mark Kelly, and Fish | Photo: EMI

Since your days with Marillion, the media has pegged you as a Genesis wannabe. You’ve been able to evolve from that and carve out your own identity. So, why did you choose to cover Genesis' "I Know What I Like" on the new album after all of that?

Because if I hadn’t done it, people would have just said, you’re just avoiding the Genesis question. People would say "Okay, you said Genesis was an influence," then they would have said "Runaway, runaway, ha, ha, ha." Then I thought, yeah, they were an influential band, and I wanna do it. And on the song I don’t think I sound like the Peter Gabriel. So, the only thing I proved, is there is a fucking difference. It’s like somebody saying to Peter Gabriel, you know, "You sound a lot like Stevie Winwood." I mean, yeah, there are some similarities in the voice, but you put the two of them together, and they’re totally different. It’s the same with Phil Collins. I mean, you can’t expect every voice to be radically different. But the differences are there, and that’s why the songs are there, to show there are differences between how I do it and how Peter does it.

Talk about your interest in exploring traditional British Isles folk music in songs like "Internal Exile" and "The Company."

When we Scottish people hear the bagpipes, the hackles rise on the back of our necks, and we don’t know why. I’m considering doing an entire album of stuff like that. There are a lot of Scottish musicians that I’d love to work with and do some traditional stuff. That’s the thing about being solo now. I can consider anything. If someone phoned up and asked "How’d you fancy doing something with Pavarotti? I’d say "Yeah, I’d really be into doing that." If Tony Banks phones up, or Jeff Lynne phones up, you know, I can do it. You don’t have to turn around to four other guys and say "Look guys, do you mind if I do this or not? I know you’re not going to be involved, and I know you’re going to have to sit on your ass for two or three weeks." Now, I don’t have to do that.

Your voice sounds stronger on Songs From The Mirror compared to earlier releases.

By doing that album, I’ve gained so much confidence in my voice, and I found a versatility in my voice that I never realized I had before. I’m playing to my strengths now. I’m finding my strengths. I think possibly with some of the earlier Marillion stuff, I was singing a bit out of my range – which was why I used to get so many vocal problems. I look back at some of the Marillion tours, it was like, five days on, one day off, five days on, one day off. I’m totally amazed that my voice lasted. I got a full check done on it last year, and it was before I did the Songs from the Mirror album, because when we were doing the album, we were gigging on weekends. This wasn’t "Knock off for four months and go in the studio" – these were gigs. So, there was a lot of pressure put on my voice. Since I’ve been solo, there’s been less, because I’ve changed the key of some of the Marillion stuff, and I’m finding I’m getting new strength in that material. I’ve been told by somebody that I should take singing lessons and find some breathing techniques, and the doctor said "You don’t need to do that." He said "Of all the singers I’ve had in here, you’ve got yourself a classically-trained voice, and the rises and timbres were all on the mark."

Do you think you’ve been successful in establishing an audience outside of the old Marillion fans?

It’s a difficult one. I mean, some people think you leave a successful band, and you automatically start at that level of success and then determine where you are going to fall. I don’t think you can expect to just walk over into the same level of success. I mean, you both take a drop. I think my first album, although it was recorded and delivered to EMI in August 1989, ready for an October release, was held up until January. So my drop went a little bit lower. And the Seasons End [Marillion’s first post-Fish album released at approximately the same time] thing needs to be factored in as well. Who were they going to back? They felt Marillion needed a lot more help than I did. But they just put them out at the same time. So, the drop I took was a bit hard. I mean, obviously the core of my following is probably people who discovered me during the Marillion times. But you know, there’s a lot of people who’ve obviously disappeared. And there’s another lot of people who’ve discovered me since I went solo. In Germany and Holland, there has been a vast influx of people who were not aware of my previous stuff.

Fish performs with Steve Rothery during a 1987 Marillion gig | Photo: EMI

Fish performs with Steve Rothery during a 1987 Marillion gig | Photo: EMI

In 1992, you proposed a series of Marillion reunion gigs, but the band declined, stating they felt your motivation was largely financial.

Oh yeah, God is crucifying me. Of course, Marillion are all millionaires aren’t they? The fact of the matter was, last year they talked of putting out a best-of album. I knew most fans already had this material, and the fact that they were doing "Sympathy" and that other track, to me meant diddly-shit. But there were a lot of fans out there that would have really been into it if we re-recorded "Institution Waltz." Now, I said to them "Why don’t we do this song? It has never been recorded. We’ll get Chris Kimsey to produce it, we’ll record it at the Funny Farm, it’s going to cost you nothing, and we’ll put it on the album." The album meant as much to me as it did to them. I mean, okay, they’re trying to reestablish their name. Where as for me, I have six songs on it which I want 50 per cent of the publishing of. And those are the songs you hope come out in five years when you have a hugely successful album behind you and then, there’s your pension. Thanks very much. And let’s make no bones about this, I mean, I love doing music, but I don’t do it for free. I mean, I don’t write for free, I don’t perform for free, because it puts shoes on my kids’ feet, and it puts a roof over my family’s head. It’s my job. And if I find an opportunity where I can make more money at my job, without prostituting what I’m coming off about, then I’m going to be more than happy. I’m not going to dress up in a Ronald McDonald costume and sing a McDonald's advert, but if comes down to material that I’ve already written and I’m really proud of, and packaging it in a better way, which might mean it’s going to sell more copies than it usually would, then I’m going to do it. And I make no bones about it.

I said to them, I said "Look, everybody’s got these tracks, if we’ve got a new track on it, it’s going to make it a far more interesting collector's item. Okay, you’re remixing ‘Garden Party’ and ‘Assassing.’ You’ve got your two tracks on it. But at the same time, the old Marillion still sells." When I get my royalty statements, Script, Fugazi, Misplaced, and Clutching are all still selling. And I just felt it would have helped that album. They came back to me after I suggested it, and they said they felt it would be a regressive step. I said "If it’s such a regressive step, why bother putting any of the old stuff on it?" They said "Oh, well that’s different." So, I just said "Okay." Then I went back to them and I talked to promoters, I talked to merchandisers, I even talked to EMI, all of whom thought it was a great idea to get back together and do a concert. It was going to be an hour-and-a-half of my band, an hour-and-a-half of their band with Steve Hogarth, and an hour-and-a-half of the old band plus the other musicians about playing some of the stuff that we would never otherwise perform as solo or new Marillion entities. And it was to be set over two festivals. One in Germany, and one in the UK. That was the idea. We were going to film it. So I would get a film and they would get a film of their new material in front of a big crowd. Great. Great for MTV and a great release for the fans. At the same time, we would have a great video of the old band and quite a special gig that we’d be able to sell to back up the best-of album. We’d also get a live album of that stuff. It would have been really good as far as I’m concerned. The fans we put the idea to thought it was a great idea as well. Nobody said "Oh, somebody’s selling out" or anything like that. Marillion came back, and they wouldn’t talk to me as a band, but their manager came back to me and said "Oh, the band have had a vote on it, and they’ve decided that they’ll never walk on the stage with you again ever in their lives." And it was like "Fair enough, so what? Big deal." And the album came out, and it sold diddly-shit. And hey, I made some money off it, and they made some money off it – fair enough. I think they probably regret the decision now.

So, your idea was to bury the hatchet and use the gig to serve as a launching pad for both entities?

Yeah, I mean, the media have taken the opportunity of the split to ignore both factions. And by doing that concert, the media attention would be good for both of our careers. It wasn’t a case of going back to the band, or anything like that. I thought it would have been a nice gesture to the fans after all the shit that’s gone down, and all the shit that’s been spread in the press. It would have been nice to walk onstage. Are we mature individuals or not? What happens if we meet up at a festival? What if we do a festival in Germany in the next year or so? What are they going to say? "Good luck, but you can’t come in, and call security?" I mean, it’s just all so stupid. All I did was leave a goddamn band. It’s not as if I raped their wives and bombed their houses. All I did was leave the band. And I think it helped them and it helped me. It helped them realize that they had an awful lot more work to do, and it made me come to terms with the responsibilities in this life and the fact that I’ve got to get on with them. They’ve got their attitudes, and whether I think it’s the right or wrong attitude, it doesn’t really matter. The decision was, they didn’t want to do it, and I said "Okay, I’m carrying on with my solo album."

Fish during Marillion's 1988 Clutching at Straws tour | Photo: EMI

Fish during Marillion's 1988 Clutching at Straws tour | Photo: EMI

Do you have any regrets about leaving the band?

I don’t regret leaving Marillion. I would have liked to stay in Marillion if I could carry on with what I’m doing now. But there would have been no way with the egos that were in that band at that time. You’ve got to remember the both of us have grown up a hell of a lot. And there is a lot of water that has gone under the bridge. Oceans have gone under since 1988. There is no way, ego-wise, that we could have done a Genesis-type model, where Phil Collins got away with a mega-successful solo career, and the rest of the band are doing their little bits, but not to the same level of success. Genesis can handle that because they’ve been around for years, and they understand the importance of certain individuals within that band. And certain individuals will offer a degree of importance more than other members. But as a band, it works as a band. Marillion could never have done that. They just weren’t mature enough, therefore I left. But there is no regret. I saw that band in Edinburgh last year. And I looked at the band and I watched Steve Hogarth perform, and I sat there and thought "I’m really glad I left them" because it was turning into a cabaret. All that soul that was a Marillion marker had gone. And they’re a totally different band with Hogarth. They’ve got different ideas and stuff. They decided to go one particular direction, and good luck to them. I decided to go in another one. I think it was the best move that I could have possibly made.

The first best move I made in the music business was joining the band, the second best was leaving it. I have the opportunity now to work with Tony Banks and Jeff Lynne. This is my third solo album. I own my own recording studio. I could never have bought this recording studio when I was in Marillion, because there would have been somebody turning around saying "I want to buy a Porsche or the wife wants to buy a new kitchen." And you would never get the finances as a band to actually get a studio, because everyone would wonder "Well, what am I going to get out of it?" When I got this place up here, I went "Yeah, I’m going to build it. I got my own finances together, I got my own structure set up. I mean it’s been difficult, and we’ve gone through some extreme difficulties in the last four years, but so have a lot of other people on this planet. There’s a lot of people in a worse state than the one I’m in at the moment. But I mean, the freedom of choice, and the power you can have as a solo artist to enable you to carry on with your life and make decisions that directly affect your life without having to bother with another four guys I think is wonderful. I love it. Therefore, there are no regrets about leaving that band.

One of the things again I like about being solo is that I make the decisions. I don’t have to worry about fucking committees. I used to hate when you’d take an idea to the old band and it would be like "Well, we have to think about it" and then they have to talk to the manager. By the time the decision comes about, all the energy has come out of it, because everybody has put their own little bit in, or they don’t like it, because I came up with the idea in the first place. So, there is a lot of crap that you just avoid. Now, if I get an idea, and I’m excited about it, I can get my band in and say "Let’s do this as soon as possible." And there is a lot of enthusiasm, and if you have a lot of enthusiasm you come up with ideas for a lot of projects. At least 50 to 60 per cent of them will make it through to completion. That’s why I like being solo. I would hate to be wrapped up in the restraints of a band again. A band is an unnatural way of life, an unnatural way of making music. There is no such thing as a true democratic band. There has got to be somebody that says "This is what we’re going to do." And that was one of the problems in Marillion. They wouldn’t listen to me anymore. [laughs]

Speaking of splits, Songs From The Mirror features two notable absences. Mickey Simmonds [keyboardist] and Mark Wilkinson [graphic artist] aren’t with you this time around.

Well, Mickey Simmonds decided to go solo. His wife had a child in November of that year. And when a child comes into this world, your outlook of life can change dramatically. Also, the tour going under influenced things. We’ve had tremendous bad luck in the last three or four years. On one tour, 48 hours before the tour was going to kick-off with the production and the trucks, the promoter went bankrupt. We lost 150,000 quid – nothing we could do about it. There was no legal comeback. Nothing. That affected everybody’s morale to some extent. Before you even start the tour you’ve lost 150 grand! And then when I came back over holiday, my personal manager Andy Field, who was also my production manager, died of cancer. And I think between those two things and the child, Mickey just felt that the best thing he could do was strike out on his own. And you know, it wasn’t like a Marillion situation. Mickey and I are great friends, and he actually played football with me a few days ago. We see each other at least once a week. He lives just down the road from me. We never fell out over it or anything like that. He was a bit confused over the direction of the music as well. Mickey had been a cornerstone on the first album, but on the second album, the guitars were playing a more dominant role in it all. I think being the keyboard player, he felt he was moving back a bit, and he didn’t have the influence that originally he had. Like I said, there was no animosity. I’m quite sure Mickey and I will be doing some more writing in the future. He does his thing and I do my thing.

As for Mark Wilkinson, The Vigil sleeve was brilliant. It was an absolutely excellent sleeve, and that was a peak. Internal Exile two months after that, I wasn’t as interested in. It didn’t capture my imagination as much as Vigil. I felt we needed to take a break. Mark and I both felt we’d run our distance as far as that road goes, so we felt we needed to take a breather from each other. He’s doing some children’s books and stuff like that, and doing some cartoon strips. He’s happy and he’s getting a bit more domesticated. Mark doesn’t like running in the fast lane of rock and roll. When the pressure comes on, it comes on heavy. Some people can take it, and some people get a bit nervous about it. I happen to be lucky. I’m one of those people that can stand with my face to the wind and take it – not easily, but I can definitely take it. Again, it’s not a problem at all between us. Both Mark and I realized there comes a point when you say "What should you do? I mean, it’s very similar to the Marillion situation. Do you turn around and go "Okay, we’re going to continue putting it out, just because Mark Wilkinson’s name is on it?" Or do we just take a break, take a different direction, and then come back in a couple of years and carry on with something? Both Mark and I decided the latter was the best way to go.

Are you a politically active person?

No. I don’t really trust a lot of the nationalist people. They ask me to do a lot of clips on TV here in Scotland, but I backed off because I don’t like anybody putting words in my mouth. There are some elements of the party I don’t like. I’ve got a lot of socialist trends, but I work in a capitalist industry. Getting involved in politics can be very dangerous. There are a lot of doors that can shut when you get involved in politics. That’s not a paranoid, conspiratorial thing, it’s the truth. There’s no point in being a sacrifice for the political party, and that’s what they want to do to a lot of artists. They love having artists involved, because it gets them in the paper. But they seem to forget that they’re politicians by nature and profession. I’m not. I’m an artist by profession and it means working with government-controlled radio. It’s very easy for Sean Connery, who’s living in Spain, who’s already a multi-millionaire and has his life. Nothing is going to damage him to any sort of professional degree. Somebody like me, who has an embryonic solo career, yeah, you can hurt me badly. Like I said, who gives a shit? I’d rather put my mark in the right place than stand on a soapbox.

Scotland is very apathetic. There might be a minority that are making a lot of noise, but the majority is very apathetic. And it comes down to brave moves. I mean, you have a chance in the general election to make a major statement on the future of Scotland, and we didn’t take the chance because there are too many materialists in this country. There are too many people going "How much am I going to make out of this?" I work in a very capitalist industry, but I’m still a caring person when it comes down to it. I still have a reputation. I’ve never ripped anybody off in my life, and I’m not going to start doing it. If I ever had an awful lot of money, I wouldn’t know what to do with it. I’d rather give it away, because too much money can actually be a pain in the ass. I’ve never been a Ferrari kid.

The only way North American fans have been able to hear your live, solo work is via bootlegs. How do you feel about the flood of bootleg Fish CDs on the market?

There are so many loopholes open, and a lot of the bootleggers are not just wee kids. They’re very dodgy people and the bootleggers have lawyers now. They’ve found the holes, and there’s no way they’re going to patch it up. I really hate piracy, but I think the record companies are to blame. I think if you took the price of CDs down, and put the price of blank tapes up, I think you’ll find things would change. Record companies are actually promoting bootlegging in a way. But there’s no way you’re going to stop bootlegging. The technology has gotten so far that they are actually body-searching everybody that’s coming into the venue. There’s going to be tapes out there, and the tapes are going to find a way to the market. The record companies don’t really like bootlegs, not because of what it does to the artist, but because they are not making money. And more importantly, the money is going to the black market. Anybody who has one of my bootlegs, will already have every import, every Argentinean single, and the Israeli single as well. They are the collectors, and these bootlegs satisfy a demand. Like I said, the record companies don’t like it because the money is going elsewhere. They’re not only bothered by the fact that the guy is spending 17 quid on a bootleg CD, but also because the guy is spending 17 quid on a CD that isn’t Bruce Springsteen, John Cougar or U2.

Record companies don’t look at live albums to be commitment albums to a contract. If you want to do a live album, it’s a separate negotiation outside the contract. It’s difficult for the artist sometimes to get the damn things out. It’s easier to let someone else put the damn things out. Record companies and the corporations aren’t helping. They’re continuing to make technology like recordable CDs and they’re shooting themselves in the foot. They’re talking about digital radio now. People are going to be sitting there waiting for their favorite tracks, and put them down on a recordable CD. Then they won’t need to go to the store and buy the CD. But the record companies are promoting this. They’re killing off the industry themselves. The main thing is the cost of the CD needs to come down, so people will want to go out and buy the original. If they can bring the cost of a CD down below the cost of a metal tape, then brilliant. Who’s going to buy a metal tape then? But the corporations don’t want that. They make more money off a metal tape, because they don’t have to pay anybody else. They don’t have rights and royalties and publishing and shit like that to deal with. They just sell an item. In the end, it’s a sick situation, isn’t it?

Is there anything else you’d like to say before we finish up?

I'd like to tell everyone in America and Canada that I’ll be back [doing Arnold Schwarzenegger impression]. I apologize for letting things take so long with North America, but just trust me. It’s been out of control. It’s been a tough four years, but we’ve become serious veterans. Now, the future's so bright, I've got to wear a fucking welder’s mask.