Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

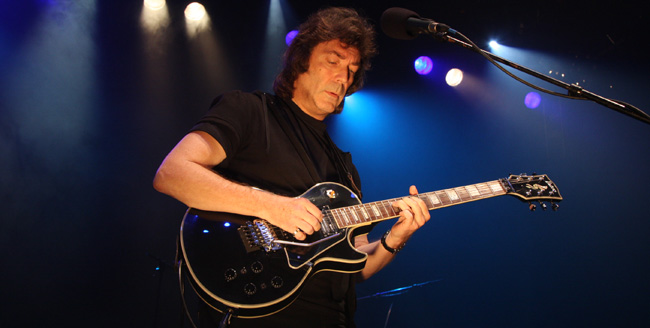

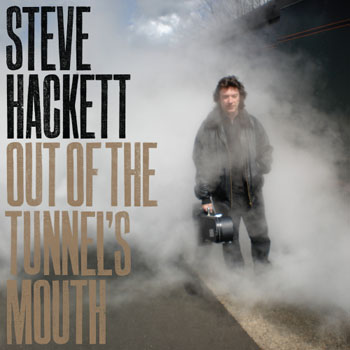

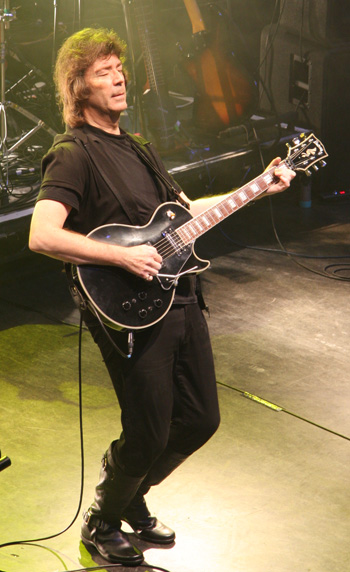

Steve Hackett

Aural Ambushes

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2010 Anil Prasad.

Steve Hackett provocatively refers to his new album Out of the Tunnel’s Mouth as a “series of ambushes.” It’s an apt description given the wildly diverse territory the album crisscrosses and connects within each song. Throughout the disc, listeners encounter Hackett combining genres including rock, pop, flamenco, jazz, and fusion, as well as Turkish, Indian and Andalusian music. And he does it fearlessly on several sonic roller coasters in which he radically shifts through multiple tempos, time signatures and moods.

Out of the Tunnel’s Mouth is one of Hackett’s most ambitious albums in a long, storied career. He was a key member of Genesis during its classic prog-rock era from 1970 to 1977. Since 1975, the British guitarist and singer-songwriter has released 30 albums showcasing a broad range of interests and talents. He’s particularly proud of his four highly-acclaimed classical albums that find him exploring the work of composers such as Bach, Vivaldi and Satie, as well as his own compositions in solo and orchestral settings.

The new album features a collaboration Genesis fans have long dreamt of. Anthony Phillips, the group’s co-founder, key songwriter and guitarist until his departure in 1970, appears on two tracks.

“Steve initially played me some demos, including one with some pretty fine, speedy 12-string guitar and I thought ‘What do you need me for?’,” says Phillips. “But these English chaps can be so stubborn, you have to resort to throwing their tea chests overboard to dissuade them. He pleaded with me to come down and when I did, he and his engineer and keyboardist Roger King were friendly and welcoming.

“They first put on the lovely, gently-rolling, country-ish chorus for ‘Emerald and Ash.’ By a fortunate quirk of fate, the Guild F212 12-string I brought with me was tuned down a tone. What would have been quite tricky in the song’s key of B Flat was suddenly much easier in C Major with all of those lovely, ringing open strings. The sequence was relatively straightforward and my part pretty much just flowed out. I also contributed to the main vocal refrain of 'Sleepers,' which has a haunting, delicate shimmering mystery about it, as well as a beautiful melancholic theme. It worked rather well combined with Steve’s many other guitar parts. It was a lovely, lucky day in the studio contributing to a very fine album.”

The new album is an incredible study in contrasts. Provide some insight into your drive for diversity.

I do love contrasts on albums and unexpected contrasts work the best. The challenge is not making them too abrupt as you lead people to places they don’t expect to go to. I love mixing genres and having something aggressive followed by something unashamedly romantic. Doing things like that represents the way I work best. There’s no formula at the end of the day. It’s always a big shot in the dark.

Out of the Tunnel’s Mouth was my third attempt at making any kind of rock album in recent times. There are two other albums that are unreleased due to contractual difficulties. It doesn’t have to do with shopping them around, but rather disputes surrounding the material. So, this was my attempt to make a rock album free of the shackles of other people’s requirements. I think that made for a more personal album. I felt I should really indulge myself with this one and make it exactly what I want it to be. But there’s no accounting for the fact that people seem to really like this one. As an artist, you hope your work will engage as many people as possible, but whether it finds a resonance among listeners is really akin to a lottery. And it’s hard to know if you’re being honest with yourself when you say “This is the very best I can produce.”

Did you directionally architect the contrasts prior to recording the album?

No, as a matter of fact, I was worried that when I started the album, there were too many pieces that started slow and then went fast. But funnily enough, listening to it as a whole, you have those peaks, troughs and undulations that make the journey manageable. If it was hitting you over the head the whole time, it would be a difficult listen. If you set out to make an exciting album, sometimes you keep things a little bit too fast for too long. You have to allow things to breathe. I think this album has a lot of breathing space. I suspect the tracks emanate from under the fingers, rather than coming in steaming. We have some pieces that do come in steaming, but I think I’ve allowed the material to become what it wanted to be. It’s a crazy thing that after all these years, I still don’t know how to write a song. I couldn’t tell anyone how to go and write one. The only advice I have is “If it moves you, that’s all that counts.” The question of “How do you touch everyone with a song” is a tricky one, isn’t it?

What insight can you provide into your creative process?

Let’s use the track “Fire on the Moon” as an example. I started that one out with the idea of writing a song that depicted what was going on with my life. In the past, I worked more often than not in the third person. With this one, I was trying to catalog the equivalent of a nervous breakdown, a divorce and a lot of dark moments from my life. I thought I’d try and put that stuff into words. I felt like I was cracking up, so why not draw a map of what’s going on and use that for the song and see if it’s cohesive. I wasn’t borrowing images from anywhere else, so there was more direct experience involved. I suspect that’s a powerful thing. It may make for a very depressing approach, but perhaps it’s more honest to say things like this in a song.

You’ve said you believe in a risk-based creative process. Tell me about that perspective.

In the days I worked with Genesis, I found the most successful way of writing with the group was to come up with guitar and vocal riffs—little, short chunks of things. That’s what tended to work best. That way, I didn’t have to write a whole song and we could fill the spaces in later. It was about capturing little sparks. A good riff can go a long way. You can repeat it, change it and work over the top of it. It all depends on the sound you’re using at the time. There’s a riff in “Sleepers” in which the song goes loud for the first time. I wanted to use the sounds of backwards instruments to play the riffs, and although the notes are really straight, the way the sounds come in are fairly terrifying. It’s a gentle song and then it comes in blasting and contrasting. There’s another approach apart from the risk-based one, though. It’s the approach of poetry and things you’ve dreamed up or overheard. So the album represents an eclectic collage process—a frantic jigsaw in which there are a thousand bits that don’t have a home, but eventually find some kind of relevance to each other and get joined up together.

Talk to me about the Turkish influences at work on the album.

I spent some time in Sarajevo with a Hungarian band called Djabe. That band improvises a lot and sometimes it’s not improvisation as we know it. There are a lot of Gypsy improvisations, as well as jazz, blues and other elements contributing to it. When I was in Sarajevo, I couldn’t help but notice the mixture of cultures that have managed to peacefully coexist there since the 1400s had been shattered in the 1990s by war. Nonetheless, what you see on the street, as well as bullet holes which are everywhere, are the occasional squares where you have a church next to a mosque next to a synagogue, and even one facing another. It’s a city of 200 minarets with a heavy Turkish influence. So, I got to hear some Turkish music there which I found very interesting. It sounded a little bit like Indian music. It seemed like similar scales were being employed. It also seemed to me you had melodies that were being played by large forces and you had improvisation on top of it. The whole swirling mass of it appealed to me. I only caught flashes of that while I was there and that’s what I tried to recreate on the track “The Last Train to Istanbul.” I find the East fascinating, musically. I wanted to set things up in a different way on that track, as opposed to the way things normally work in Western music, in which you have somebody singing, then a riff or a solo. It’s nice to have all those things happening simultaneously at times.

The album was recorded in your living room. What can you tell me about the recording environment?

Because of some personal difficulties I was having with access to my studio, I decided to work at home. That meant I had to forego the use of drums, but it meant the thing grew up in a different kind of way. It grew up in the computer initially and then we took those computer sketches to players, a number of whom also work in their living rooms. They would either send stuff back to us or come to visit. When I say “us,” I mean Roger King and myself. Roger recorded the album using Logic and it made for a very homegrown feel. I think that characterized the album. Also, we were monitoring at very low levels. The guitars were recorded at a very low level, but I was trying to recreate the sounds I used before in my home studio when I used Marshall cabinets cranked up really loudly. I wanted to see if you could do that in miniature and so far, I have been very pleasantly surprised with the results.

Describe how your guitar approach has evolved in recent years.

Years ago, I came up with something that was subsequently called tapping. You could first hear it in 1971 on the first album I did with Genesis called Nursery Cryme. I was doing tapping work which we used to twin with keyboards, so you couldn’t tell the difference between the two. I’ve come up with many techniques, both acoustic and electric since then, but naming them would be a real challenge. What I can say is that I think I record my guitar playing more slowly these days. I’ve got to the point where I can play as fast as I want to. I don’t think I need to play any faster than I currently do. That means I can exploit that ability when I play live because it’s exciting, but on record, I play more slowly. I concentrate on tone. I get worried when I hear people engaging in guitar solo after guitar solo that involve as many notes being crammed in as possible. That sounds like sport to me. Olympic guitar playing is something I find very wearying. I think speed has its place, but I prefer to use it the way a composer might when they construct a violin concerto. Yes, there will be death-defying pyrotechnics, but I want to have great melodies there too. The difference between being a virtuoso and being a performer is a quantum leap.

Ultimately, I’m after something very simple. I’m influenced by masters like Bach, someone who had tremendous technique and complex underpinnings for every phrase, yet the musical effect is very simple because things are so focused. I’m a great classical fan, but I do listen to music from everywhere, including jazz, atonal, and world music including Gypsy and flamenco music. I want to incorporate elements of all those things into what I do. It’s the sharp contrasts of dissonance and their sweet resolution that I find interesting. It’s almost like expletives and poetry side-by-side, or even the sacred and profane. It makes the sweet sound more romantic and the savage moments sound sharper than ever.

You believe guitar tone is as much about the fingers as any equipment that might be invoked. Elaborate on that.

I do, because your tone really depends on how you’re going at the instrument. You can do a lot with just your fingers. I think if you’re trying to do the same thing as everyone else, you have to play in a certain way. But if you’re looking at the corners of the instrument that haven’t been fully exploited yet, the answer to the future has to be in the margins, as far as I can see. So try hitting the guitar with something it shouldn’t be hit with, instead of your nails, fingers or bottleneck. Hit it with a vibrato, a disengaged boom or a tremolo arm. Or don’t actually hit it at all. Stroke the strings and caress the instrument into life.

Many guitarists are obsessed with the upper harmonic area. It’s precisely where the guitar sounds most like a human voice. When you play in that area, the guitar really does sound like a voice and doesn’t have to play second fiddle to the singer. I find that if I play very lightly in the main, I can get more harmonic in the sound. That’s why I use .008s, which are very light gauge strings. I do a lot of finger vibrato these days as well and use less tremolo. Today, when I play a phrase, I have to audition all the possibilities to hear what sounds best.

I think guitars are marvelously expressive instruments and I don’t think they’ve been over-explored yet. There’s still plenty to do on the instrument. There’s something really wonderful about it. It’s the equivalent of a violin with lead boots underneath it. It also has aspects of a sax, with the ability to rip and tear. The idea of one instrument emulating another is one I find really fascinating.

What guitars did you use on the album?

I used my two custom-made Fernandes Les Paul shaped-electric guitars, each with a Floyd Rose and Fernandes sustainer system, and standard mahogany/maple construction. One is a gold-top version from 2002, the other is a black model from around 2005. I love the sustainer system. Years ago, I figured out that if you took away percussion and decay from the instrument, you’d be left with something closer to the violin. I was interested in the tone of the guitar without it being compromised by the elements that typically characterize it. There’s a little bit of steel-string work on the album performed on a Black Yairi I was given in 1996. I also use a 2005 Yairi acoustic with a deep cutaway, shallow body, because it has a bit more snap, particularly for the flamenco-inspired material. In addition, I played a Jones electric sitar guitar on “Last Train to Istanbul.”

Describe the signal path you used when recording the album.

I typically run my electric guitars through combinations of a Vox V847 Wah-Wah pedal, DigiTech Whammy pedal, Tech 21 SansAmp GT2 preamp, Korg KVP-002 volume pedal, and Line 6 DL4 Stompbox Modeler Delay multi-effects pedal. From there, we would prefer to typically record via my preferred Marshall 1987x head and single Marshall 1960A cabinet with a couple of mics—one close and one a few feet away. But given the circumstances this album was made under, we had to do without the Marshalls and used Logic 8 plug-ins for amp and speaker simulation instead. All acoustic guitars were recorded with an AKG 414 mic into a Focusrite mic amp.

I find the amp modeling universe very interesting. I did things like record a clean guitar for “Still Waters” but then added distortion after the event. It wasn’t part of the original performance. At times we tried to emulate the Marshalls and Eventide compressors. I’m not driven by equipment though. I have a symbiotic relationship with Roger. I’m myopic, so I can’t see what’s happening on the screen. He’s the one who brings up various things on the screen and I use my ears to decide what to use and reject. I’m purely driven by sound.

You use the DigiTech Whammy a lot in your work. What do you enjoy about it?

I love sticking the guitar through a fixed wah on full bass and then using the DigiTech Whammy to take the octave up and then to the octave above that. It creates a flute-like sound. Also, I used to use a Rose Morris Duo Fuzz with a two-way switch on the early Genesis stuff to create really high harmonics. And I can get the same thing from the DigiTech, because it functions as a more mobile harmonizer, by letting you climb and jump octaves. Recently, I started using the ring modulator settings too, which are a lot of fun when I’m playing blues. I use it live more than on the album. You can do really lovely, wacky things with overtones and notes that sound almost humorous—like making your guitar make Donald Duck sounds.

You collaborated with Anthony Phillips on the new disc. Describe how you worked together.

I’ve known Ant for a long time. I had been trying to talk him into playing something with me for over a year and one day he showed up thinking it was for a rehearsal. Cunningly, I had an engineer here and we were working on some stuff. I said to Ant “Why don’t you put down some ideas? I won’t use anything you’re unhappy with. I’ll get out of the room until you have something you’re happy playing.” Five minutes later, he had already come up with stuff for the choruses on “Emerald and Ash.” He detuned his guitar so it had gone down a tone-and-a-half. The chorus was in B Flat, but he played in C position with open strings and I said “That sounds absolutely gorgeous.” The 12-string is Ant’s area of specialty. So, I had two electrics going on that chorus already and he did two 12-string tracks with that jangly, signature Genesis guitar sound. He also did some stuff for the chorus of “Sleepers.” He tracked up a couple of things with a slightly country feeling—almost Fleetwood Mac-like. That sounded absolutely beautiful to me as well. So, I employed the same philosophy. I said “I’m going to leave the room. The last thing you need is another guitarist looking over your shoulder telling you what to do or slapping your wrists. I’ll get the hell out of your way and let you do what you do best.” I was thrilled with the stuff he came up with. I hope to do more with him. I felt he really brought the material to life.

What did it mean for you to work with him?

I had long wondered what it would have been like if Ant and I had worked together in Genesis at the same time, rather than he being the predecessor and I the successor. Obviously, I worked successfully in Genesis with Mike Rutherford and Tony Banks. We all played 12-string and were fans of his sound. That was something we all shared in Genesis—the idea of lots of 12-strings all arpeggiating at once. It created a very loose, impressionist sound in which you couldn’t really tell if you were listening to keyboards or guitar—especially when we’d put them through Leslie cabinets. These days, we do the virtual equivalent of that using rotary sounds. That cloudy, impressionist thing is very attractive. You can make the sound more jangly if things are close-miced and if you put them through other effects, they become more washy. It’s almost part of what defines those early Genesis albums like Trespass, Nursery Cryme, Foxtrot, and Selling England by the Pound. After that, it changed. You get occasional moments on The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, but not much. You got it again on Trick of the Tail and then I headed into nylon territory for Wind and Wuthering.

What was it like for you to fill Phillips’ shoes when you first joined Genesis?

I found it very difficult. So much of the music was written and initially, I was joining them as a live guitarist trying to decipher the guitar parts. It wasn’t until I made my first album with them, Nursery Cryme, that I began coming into my own. I’m aware that this is something that’s difficult for guitarists. I read something recently in which Peter Green talked about filling Eric Clapton’s shoes when he joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. He was under a lot of pressure with Eric being such a huge star. A difficult act to follow, even though Green was stunning in his own right. Ant was Genesis’ much-loved guitarist, their working partner, and a school chum of everyone’s going back to the early ‘60s. It was very difficult for me to understand the language they had all grown up with.

My dogged determination to keep chipping away at the thing was what kept me in good stead with the band. I always wanted to improve. I knew I hadn’t got it entirely right at the start, so I made myself jump through hoops of my own invention in order to push the boundaries. I wasn’t content to just play 12-string with a plectrum. I wanted to play it with my fingers and then employ that technique on the nylon guitar. I also brought in Segovia and flamenco influences into the band, in addition to different types of trills, vibratos and ways of making the guitar feed back. I would take the bottleneck and use it past the pickup and scratch it along until it engaged with a feedback note to create a seamless joint between the two. It’s all in the details for me. Being really demanding with yourself can help push you into new territory.

The Genesis back catalog has been extensively remixed and reissued in recent years. Do you feel the guitar balance shifted to your favor in the new editions?

I think it has. I think the new mixes are far more guitar-centric. You’ll hear much more guitar work on The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, for instance. From the word go, you can hear a fly buzzing around, which is a guitar put through two fuzzboxes. That was something I did in 1974 and it’s nice to be able to hear that now after all those years. It’s great that with the passing of time, the material has been remixed in the guitar’s favor. I was standing on the sidelines during the process, receiving rough mixes for approval. There was very little that I went in and changed. I was very pleased with the end result.

Is it strange to think these new mixes may supersede the original mixes in the long-term?

I’m unsure they will, with the availability of downloads. It seems to me what we have are contrasting mixes. Each mix has something the other mix won’t have. Something goes in and something is lost as you change perspectives on different mixes. But overall, I would say the new mixes are better. This will be sacrilege to hear for someone who believes their childhood has been messed with. They are simply alternative mixes. There is no definitive mix with any album. Hopefully people will appreciate both.

Back in 2006, Tony Banks, Phil Collins, Peter Gabriel, Mike Rutherford, and yourself held serious discussions about reuniting for a series of 10 Lamb Lies Down on Broadway concerts in Europe and America. Gabriel ended up declining. What’s your perspective on that situation?

I still feel it would be great if it happened with Pete and me. I’m up for it. Have guitar, will travel. When they approached me I said “Okay, fine.” Then for one reason or another, Pete decided he didn’t want to do it. I’m forever playing the diplomat these days and I hope there’s a diplomatic solution. Maybe it’ll happen one day or maybe it won’t. It’s been a long time since I played with Genesis. There’s been a lot of water under the bridge. I’ve even recorded Bach pieces since then. I’m not sure how acquainted they are with my Catholic tastes. I’m happy to play anything these days. So, beyond that, I have a great band that I’m currently working with. I can call them up and work with them anytime. And I’m also working on a forthcoming project with Chris Squire.

You’re equally committed to the electric and acoustic guitar universes. Describe the contrasts you find appealing.

They definitely do influence one another. I love what you can do with one nylon guitar. I love the different tone colors that are possible. You can conjure up a whole world with one color. I also love the limitations of the instrument. There is something very pure about that. I think the guitar is a miraculous instrument. When I heard Bach pieces written for violin and cello played on guitar, I realized that’s probably the finest music you’ll ever hear on the instrument. And it wasn’t even written for the guitar in the first place. It’s written for four strings and then transcribed for six strings, which provides those pieces an added dimension. Now, there’s the other side of me, who is the rock and roller, that wants the guitar to scream and make all those bestial noises, and have it morph from one thing to another. The guitar is really my synthesizer in a way. I want it to become all the things it can possibly be. I’m still ambitious in terms of what it’s capable of and I want to be surprised every time I pick it up. I’m really still searching. It’s still a shot in the dark every time I pick up the guitar.

You recently said your current trajectory is designed to fulfill the promise you showed in the earlier days of your solo career. Tell me more about that.

Back then, I was able to show a lot of contrasts. I was playing a genre of music that was a mixture of styles, which wasn’t yet named “progressive rock.” Once it acquired that name and suddenly became unfashionable, we went through many decades of the guitar being an adjunct to the mainstream approach of writing pop songs. It seems now that it’s going full circle and people are once again interested in players doing what naturally comes to them, including strutting their stuff. That’s certainly the case back home in England. Progressive stuff is taking off in a big way once again, and I find that fascinating, given all of the things I was pilloried for previously. Today, I hear bands using classical instruments, changing time signatures, taking an episodic approach, using concepts in songs, and employing non-mating-ritual-based lyrics. So, music is telling a story once again. It seems people aren’t afraid of using epic proportions either. Some bands are using real strings, not just mellotrons or synths as we once did. They’re saying “Let’s have real orchestral players in there as well.” It’s wonderful that orchestras are back in fashion. It’s a healthy time for music right now. Very few things are being decried. There’s room for everyone and more genres are being celebrated than ever.

I think you’ve always had an element of that in the American scene. The U.S. approach to genre charts meant that a rock act was going to knock something off the country charts. Whereas in England, at the end of the ‘70s, some bands had a single purpose, which was to knock everyone else off the perch and establish something else in its place. I’m talking about the anarchy that was punk. I was one of the people who went out and bought the Sex Pistols’ first album, not realizing that it was going to begin a movement that was going to be used against what I stood for, which was quality. I don’t want ignorance to be hailed as a virtue. People who can really play, sing and write songs—let’s hear them. Let’s welcome everyone. Let’s not be prejudiced by age, race, creed, color, or religion. Music is big enough to embrace everybody.