Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Hansford Rowe

Truth is the antidote

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2017 Anil Prasad. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution, No Derivatives license.

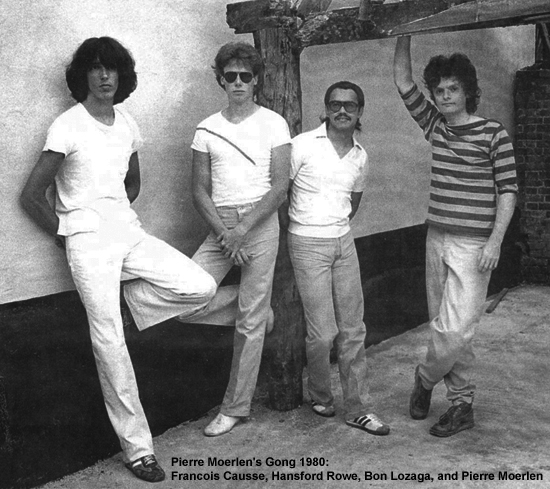

Hansford Rowe has his eyes on both the rear-view mirror and the road ahead. The bassist’s career spans five decades, first coming to the fore as part of Pierre Moerlen’s Gong and Mike Oldfield’s group during the late ‘70s. Together with the late Moerlen on drums and percussion, Rowe was half of one of the great rhythm sections of the era. The two were a tight, cohesive unit capable of playing incredibly intricate and adventurous compositions.

The Gong family remains integral to Rowe’s musical universe. Between 1994 and 2010, he co-led Gongzilla with guitarist Bon Lozaga. The group was a descendent of Pierre Moerlen’s Gong and its fusion-oriented output, but with nods to the singer-songwriter and jam-band realms.

Rowe’s new quartet, Gong Expresso, offers another evolution from Pierre Moerlen’s Gong. It features Benoit Moerlen on vibes and marimba, and Francois Causse on drums and percussion. Along with Rowe, both were part of Moerlen’s group during the period that produced the classic Expresso II album from which the new band takes its name.

Gong Expresso also includes a newcomer, guitarist Julien Sandiford, who was part of HR3, Rowe’s previous jazz-rock trio. In fact, Gong Expresso’s forthcoming album Decadence initially began life as a new HR3 recording. Once three Gong members became involved with it, the group felt a new band name more reflective of its collective history was appropriate.

Rowe's Gong-related activity is one element of a much larger picture. No Other, his 1999 solo album and Love’s Appeal, a 2010 duo effort with guitarist Jordi Torrens, took a song-oriented approach. Rowe is also a member of renowned avant-garde composer La Monte Young’s ensemble, performing in multiple projects involving just intonation.

Rowe has also worked with an impressive array of performers as a sideman and collaborator, including Allan Holdsworth, Gary Husband, Bireli Lagrene, John Martyn, and Happy Rhodes. In addition, he’s a faculty member at Bootsy Collins’ Funk University.

Describe how HR3 morphed into Gong Expresso.

When Bon Lozaga and I put Gongzilla on hold in late 2010, he went on to work with his other bands Tiny Boxes and Soften the Glare. I recorded Moment with the wonderful Catalonian guitarist Jordi Torrens and then started HR3. That was the beginning of an ever-deepening writing collaboration between Julien Sandiford and myself. He was 20 and is now 25. As we began work on new material for the second HR3 record, we decided to stop rehearsing the new tunes as a trio with the drummer Max Lazich and prioritize the compositional elements. Drummers can be difficult on many levels for a composer and we wanted to let the tunes tell us quietly and intimately where they wanted to go. As Julien and I worked toward something fresh and clean, we went through much exegesis. This led to Benoit Moerlen and Francois Causse getting involved in a really magical way.

We realized a lot of the tunes were going to sound good without a classic drum kit. Francois is primarily a European tuned percussion player, which was his role in Gong. That means he’s used to playing patterns and thinking classically, as opposed to a pure jazz improvised background. Several of the new tunes are formal in terms of taking a minimalist approach and he was great at adding to that. Who knows how our personal influences map our path, but I know that when Julien and I adapted our tunes to tuned percussion a la Gong, it was a perfect fit. We recorded eight tunes in nine days in Paris, which included a cancelled flight, a cracked rib and kidney stones requiring two trips to the local emergency room during that time. Yet, we were able to use all eight tunes on the record. This was above average synergy.

What are the musical linkages in the Gong Expresso band that connect it back to the classic ‘70s Gong Expresso II album?

Benoit’s history with Gong goes all the way back to the You album. Francois and I joined at the same time in 1977. I met Richard Branson who ran our label Virgin at the time in Notting Hill in London. We then recorded Expresso II at Pye Studios and mixed at Britannia Row. Allan Holdsworth was in an incredibly fruitful period. I will always remember when he played me a tape of Bruford sessions in my newly-purchased Alfa Romeo 1750 GTV. I had just spent my entire advance on it.

These were good days for studio recording. We recorded at studios including Konk, Trident, Virgin Manor, Townhouse, Island Studios at Basing Street and more. Francois was 17, Benoit was 22 and I was 23. Pierre and I were so tight then both as a rhythm section and as hardcore drug enthusiasts. Benoit, Francois and Pierre had been classically trained in percussion with Jean Batigne and Les Percussions de Strasbourg. I learned a lot from Pierre’s approach to rhythm. He loved my American instincts. The four of us were almost constantly together for the next four years.

The records we made in the ‘70s have endured well and the new band name evokes Gong’s jazz-rock period under Pierre’s helm. There are true enthusiasts out there that are happy we are recording together again, including the current version of Gong with Orlando Allen. The name and branches are the stuff of lore now and our references are impeccable. Jonas Hellborg told me a couple of years ago I would be nuts not to do this. So, it’s his fault. [laughs] Also, Gong was never really famous enough that people can point to us and say what we’re doing is suspect. We’re not trapped by having to play the old tunes. We’re doing this because we want to.

Why did you name the forthcoming Gong Expresso album Decadence?

Its purpose is to counter decadence and get at what we consider to be true. Truth is the antidote to decadence. Decadence is both in us and all around us and whatever we can contribute to making things better and more beautiful is really important.

How did HR3 come together initially?

After I stumbled upon these two young musicians, Julien and Max, I realized we had a good, instant rapport. So, we decided to form a band. I met Max through Facebook, and he recommended Julien. Max was into Magma, Zappa and avant-garde prog. He’s a tremendous drummer with a lot of character and bulldog vigor. Julien is like a deep old soul with the ability to play lyrically and see long distances ahead of him when he plays.

Contrast the difference between playing with emerging musicians versus people you’ve worked with for decades.

It’s viscerally different, but both have their joys. Gong Expresso has both elements, which is a combination of youthful vigor and the deep relationships I have with Benoit and Francois. We have so much common history and so many musical references. And you get all the other complexity of long-term relationships that go with that. With the young players, I like the fact that they don’t have the same reference points. That lets us go in some new directions. In a way, I’m mentoring them and I have to explain what I’m looking for. They’ll ask lots of questions and I consider it a big responsibility to explain things as I see them. The younger guys are also not as cynical as people who have been doing this a long time. They’re in the moment and trying to figure out the right thing to do. Older musicians like me might be full of bruises and burns. [laughs] So, it’s nice to have the younger musicians challenge me to play with the same sincerity and insouciance I had when I was starting.

Both Gong Expresso and HR3 explore the jazz-fusion universe. What are the keys to keeping such an established genre fresh and interesting?

It’s true that both groups are in a category where there has been a lot of quality work done previously. The mandate I gave myself is that we would keep things as simple, precise and honest as possible. We’re trying to be as true to ourselves as we can. We go where the tunes take us. I want the tunes to spotlight how we move from one point of interest to the next. I also like to focus on micro-dynamics and ensure precisely which notes are chosen for the pieces. That means a lot of work with much attention to detail and hopefully that comes across with both groups.

How do you look back at your time with Gongzilla?

It was also related to the jazz-rock of the late ‘70s, which Bon and I both lived through. I was playing that stuff around the world at the same time Jaco Pastorius was. Jazz-rock was burning out at that time. So, the association is personal. I think Pierre Moerlen’s Gong was a very special thing and I feel connected to it. I’m also responsible for it to some degree. A lot of people like that music, too. So, Bon and I wanted to play good jazz-rock and have a vehicle for writing tunes.

The two of us were good partners and worked together as Gongzilla for many years. We had a natural relationship and rapport. We went through many ups and downs with it, but the band never really broke through. It never gained enough momentum to the point where it easily paid for itself. After 14 years as Gongzilla, we had developed a small fan base. We toured and sold records, but it just barely stayed above water. As a commercial endeavor, it wasn't very successful and after a while, we got tired of pushing the rock up the hill.

I don’t regret doing Gongzilla. We did it for 14 years. We rode the whole wave of the idea that since the major labels no longer mattered, indies would have a chance to do things on their own. It turned out to not be a particularly good thing. We ran our own label. We had indie distributors working for us, trying to sell albums around the world. We couldn’t negotiate pricing and we had very little power. But the albums still stand as statements. That’s the main thing.

How is Gong Expresso different from Gongzilla?

Benoit and Francois are more integral to the focus. Gongzilla was more about me and Bon. We wrote all the tunes in Gongzilla and decided the way each album would go. Sometimes Gongzilla tunes sounded like classical Pierre Moerlen’s Gong pieces. Sometimes they sounded like jam-band rock. There’s still a small group of fans that want to hear the Pierre Moerlen’s Gong approach. We’re not famous enough to make any real money off of it. So, this is about making good music, respecting the legacy, but not being particularly nostalgic. The new record is just that—a new record.

Love’s Appeal, your duo album with Jordi Torrens and your solo effort No Other were more song-oriented. Why did you choose that focus for those recordings?

Writing songs is really hard for me. Doing instrumental stuff is a bit easier, although that’s not why I chose to go the instrumental route for Gong Expresso and HR3. When I did Love’s Appeal, writing songs was on my mind. The final Gongzilla stuff also included a lot of songs, which I’m quite proud of. They were outside of the usual vein of Gongzilla’s jazz-rock stuff. Bon was happy with them as well. I love good pop songs. When you’re working with lyrics and a song format, you have to figure out how to speak honestly and make a clear statement. And it has nothing to do with improvisation. It’s a hard thing sometimes to not just improvise and play a bunch of stuff as someone that comes from the jazz world. The muscles you develop are really about working within the moment. With songs, it’s about having the music tell you where to go too, but in a different way.

No Other includes a song called “Rouler” written by Ivan Doroschuk of Men Without Hats. How did that collaboration come about?

He’s a true artist. A producer we both know in Montreal put us together when he was working on some demos. That’s how I first heard “Rouler.” It was originally an up-tempo, kind of disco tune, but I made it into a slow ballad. Ivan writes beautiful lyrics in both English and French. He can write songs of equal value in both languages, and that’s phenomenal to me.

You’re based out of Montreal. Describe the journey that led you there.

I’m American, but moved to Paris and London when I was part of Pierre Moerlen’s Gong. After it stopped in 1980, I settled in Paris. I spent a lot of time working in France with Gong. I played with a bunch of different French artists who eventually took me to Quebec City to record. Back then, when French people had a recording budget and could get out of town, they preferred to go somewhere not too destabilizing, so Quebec was popular. I did a couple of records there with Charlelie Couture and Jean-Yves Lievaux. I met my wife when I was doing those back around 1983. I had lots of drug problems in those days and ended up bottoming out in 1984 in Paris. That was a rough period. I ended up going to treatment in the States at Hazelden. I’ve been sober ever since. I came back to Quebec City after treatment and begged my wife’s forgiveness and we’ve been together ever since. We moved to Montreal not long after that, had kids and stayed there.

How did you first connect with Pierre Moerlen?

We first met in New York City in late 1976. I was 22. He had burned out with Virgin and Gong in general. The band had transformed multiple times in a short period. Steve Hillage and Daevid Allen had left and there was some question of what to do next. He took a break, came to New York City and we met by chance through mutual friends. We played together and hit it off. He played me the Gong album Gazeuse! which was the last one he had done, and the first one with Allan Holdsworth, and I thought it was really special stuff. Allan soaring above the tuned percussion players was great. I thought “If we’re headed in that direction, I’m down with that.” So, I went to Paris with Pierre. We had no money. I had to borrow money just to go. We met with Richard Branson in London after reforming the band and got re-signed as Pierre Moerlen’s Gong. Those were heavy days. Suddenly, we were hanging out with Steve Winwood, John Martyn and Mike Oldfield. I also played with Gary Husband for the first time.

What was Branson like in those days?

He was the head of our label and had us recording at a variety of major London studios. He seemed like a perfectly genial guy at the time. The whole Virgin team was. They were still a relatively small company. They were on their way to becoming big, but not quite yet. It’s hard to be too analytical because I wasn’t a sober adult in those days. I was a kid and these were grown-ups with money to me. That’s how I looked at it. They had the money and we wanted an advance so we could get into the studio. We were signed to old school cross-collateralized record deals, which are now considered unethical. But we got the advances and basically broke even during our most successful periods and I’ve been broke ever since. [laughs]

You either figure out a way to keep going or you don’t keep going. Through some measure of luck and pig-headedness, we made it work. I’ve been through every phase of the music industry since 1977. The late ‘70s saw disco and punk come in and pollute everything. Both disco and punk were saying “Fuck you” to everything. But here we were in the middle of that playing instrumental music with a Virgin record deal. We could never get a clear accounting of anything from the label. They were collecting our publishing and paying back our advances from every conceivable source and our manager did not make things any clearer for us. But I don’t regret any of it. I don’t hold any of that against Branson. Virgin was cool. Between Gong and Mike Oldfield, I got to play instrumental music in front of tens of thousands of people and record in good studios. So good on Richard for enabling us to do that.

Tell me more about the Mike Oldfield linkage to Gong and how you ended up recording and touring with him between 1979 and 1980.

Pierre asked Mike to participate in the sessions for Gong’s 1979 album Downwind and he did. The album was mostly recorded at Mike’s studio in Bath. No-one knew this until now, but Mike plays bass from the concert tom solo right through to the end of the middle section on the title track. I played bass at the front and end of the tune, where it’s funky. The rest is all Mike.

Gong also did a couple of shows with Mike joining us in early 1980. As a result of playing on Downwind and then Pierre working more with Mike, I became part of Mike’s picture. Mike one day said “Bring Hanny to the session” and I went. That’s the way it started. Benoit was also playing with Mike in those days quite a lot. So, basically, Mike used the Gong rhythm section for certain projects. It’s what led me to working on his 1979 Platinum album and the big tour in 1980 we did.

You mentioned how punk and disco colored the music scene. Oldfield’s Platinum album is partially seen as his sarcastic reaction to those genres. What’s your take on it?

Platinum isn’t my favorite Mike album. Ommadawn and Tubular Bells are my favorites. On Platinum, Mike was in his studio head, constantly overdubbing, flying things into the tracks, switching things out, and replacing my section with his own bass playing, and vice-versa. It’s hard to even tell where I’m playing sometimes. But you’re right, tunes like “Punkadiddle” were a parody of punk.

Even with Gong, on the Expresso II album, there’s a track called "Soli" during which you’ll hear Pierre and me do two fills based on disco octaves. They’re there right in the middle of Allan’s solo. Those things were a little wink to disco. We didn’t do much pandering like that, but there are a couple of other tunes Pierre did where he’s essentially trying to create a pop tune with disco-ish or funky-ish elements. Everyone in those days was overwhelmed by the success of disco and punk, compared to the lack of success of all other kinds of music. You couldn’t help but deal with it one way or another. Musicians outside of disco and punk would get reactive about it and it sometimes found its way into their music. But look at what other bands that survived from the ‘70s into the ‘80s did. They often became satirical versions of their former selves as they tried to stay relevant in the ‘80s. I survived those years fairly unscathed because I was sobering up and didn’t make a bunch of stupid records and videos. [laughs]

What was it like to work with Oldfield?

He was a totally cool human being to me. We did a lot of different things together. He would come in to just overdub a solo on a record. We would spend time at his house and rehearse. He was always calm, respectful and a little bit formal. On tour, he could be funny, but he kept a certain distance from everyone. He’s an introvert. I got along with him and sometimes we butted heads a little bit. I didn’t want to play with a pick and he wanted me to. But I really enjoyed working with him. He doesn’t fuck around, either. He expects you to do your job—as well he should. I enjoyed working with him tremendously.

It was awesome to play tunes like “Tubular Bells” and “Ommadawn.” I wasn’t that much of a fan until I got to play with him. So, I got to enjoy the tunes as I was learning to play them. I became a fan as I was performing them with Mike. There are great bass lines in his music. A lot of them I played my way with my fingers, but they were his bass lines. They were written out and they’re awesome. He makes such great music. It was a lot of fun and sometimes I regret not being more appreciative of the experience while it was happening.

Why didn’t you work with Oldfield after the 1980 tour?

It was mostly my own fault. When Gong stopped in 1980, I had to choose between going on tour with Mike or doing a trio with Allan Holdsworth and Gary Husband. It was a really hard decision, but I really wanted to continue working with Pierre and Mike was a big gig. But I was doing lots of drugs and went back to Paris after the tour. It took me until 1984 to sober up. It was a period of hardcore drug use. I was living apartment to apartment and didn’t have any money.

What can you tell me about why Pierre Moerlen’s Gong initially came to an end in 1980?

I think it was probably a natural conclusion. Arista dropped us. We did the Leave it Open album, which was the final record on the contract. We recorded it pretty much ourselves. It sounds okay to me, but it wasn’t of the audiophile quality of the earlier records. I love the music. It was our final statement together. Francois plays a lot drums on it. Pierre also played a lot of keyboards and vibes on it which gave it a special flavor. There were no further record deals to be had. It was the end of 1980 and the labels were doing a lot of house cleaning and we were part of that.

During the late ‘80s, the band reemerged for three more albums. Not much is known about that period.

What happened is Pierre got a little budget together a couple of times from people he was involved with in Germany. So, we did two studio records and a live album in the late ‘80s. They have a few good moments, but most of it is kind of patched together and not very well recorded. It was hard for Pierre to realize a vision with these albums because he was completely distracted by his own problems and budget constraints. He would get together with a group of guys and fly me in to overdub bass on top of what they did. I’m not very proud of those records. They aren’t horribly embarrassing but they’re not particularly good, either.

What did Moerlen make of Gongzilla?

He liked it and hated it. He played with us on a tour of Europe once. He supported the band, but sometimes he was either too out of it or angry to participate. But even on tour, he played well enough. Sometimes he was great. But he was still getting high all the time and could get really difficult.

Many tales have been told about Moerlen. Tell me what the reality of working with him was like from your perspective.

We were both active drug addicts. He was my best friend in many ways. He was my drummer I and I was his bass player for many years. It was like a marriage and there was love and hate in it, and periods of ups and downs. We were stupid too. I couldn’t understand some of his decisions but I loved him and loved playing bass with him. His way of thinking about rhythm is something I adopted. I hadn’t made real records until we were together. Even though we were close to the same age, Pierre mentored me in many ways. Musically, with Pierre there was no fucking around. If you didn’t play tight, it’s because you fucked up. There was never a question of swinging something this way or that way. You were either correct or incorrect. It was a very European classical training approach, even though we weren’t playing European classical music. So, I’m glad I had that experience.

Pierre never sobered up and he went on a roller coaster of substance abuse for the rest of his life. It was a hard thing to watch. Some people sober up and some people die. Pierre just kind of expired one night in 2005. We weren’t in touch during the last years of his life. I had last seen him in 2002 for a tour we did. He passed away in France. I was in the States. There were times during the last Gongzilla period when we were on the outs too. He would be extremely difficult sometimes. But those were the ups and downs of the last few years of his life. He could be very paranoid or very friendly.

Allan Holdsworth just departed. Reflect on your time working with him.

When Pierre played Gazuese! for me in New York City, I heard Allan for the first time. I was into Miles Davis, Chick Corea, Steely Dan, and Earth, Wind and Fire. When I heard Allan’s guitar playing and Pierre’s drumming, I was ready to drop everything and head off to the unknown in Paris. I wrote “Soli” knowing Allan would be soloing. He was as idiosyncratic in the studio then as ever but also jovial and funny as hell.

Allan didn’t really enjoy recording in the normal sense. Recording is a paradox. When being creative, you have to risk breaking things and having accidents. It’s not really creative without some destruction and that causes stress and suffering. We all find ways of managing this. If you don’t, nothing gets finished. Once when we played a show in London with Allan, he had at least 10 pints before going onstage. He played great. We all were pretty resilient in those days. But it takes its toll. Allan played with us on and off over the years, including some great stuff with Gongzilla in the ‘90s. I loved him and it pained me to see him suffer. Success is a series of failures that turn out relatively well. I think we all feel blessed to have known Allan whether personally or through his music. As an artist, I think he was successful.

How did you first connect with La Monte Young?

I met Jon Catler, a New York-based guitarist in 1988. He introduced me to just intonation and the idea of playing in alternate tuning systems based on the harmonic series. He was already advanced at this stuff and I was a complete newcomer. I felt embarrassed that I didn’t know anything about it then and immersed myself in it for the next couple of years. I studied a lot of Harry Partch. I had basses made by Warwick, who I’ve worked with for 30 years, dedicated to just intonation.

Jon and I started working together and he had already been working with La Monte. He helped tune the piano and assist La Monte during the Well-Tuned Piano period. He has worked with La Monte in a variety of formations, including the Forever Bad Blues Band. In the mid-‘90s, I was asked to play in a big band with Jon and La Monte. I remember playing with a 17-piece band at the Dia Art Foundation in New York during which we played a sustained 31-note chord against a drone for three hours. It was a very tough gig requiring a lot of concentration to do properly—as always with La Monte.

We recently performed with a new project called The Sundara All-Star Band with La Monte, his wife Marian Zazeela and Jung Hee Choi on vocals, Jon, Naren Budhkar on tabla, and myself. We played three concerts late last year and we’re hoping to do more.

What does it mean for you to be associated with such an influential composer?

He’s a really down-to-earth, cool guy. He’s very special and playing with him is very destabilizing on many levels. [laughs] La Monte lives life to the fullest. He is the classic description of an artist with no hedging or compromise whatsoever in how he approaches his work. He approaches everything with the utmost seriousness and there are idiosyncrasies that come along with that. He’s a one-of-a-kind guy and when you work with him, you must suspend judgment and go for it.

Describe how Young directs his musicians.

He doesn’t give you a whole lot of indication of what he wants. It’s a classic technique of a certain type of serious artist. They don’t want to play with you if you don’t have ideas of your own to bring to the table. When you’re in La Monte’s boat, you’re expected to row. Nobody’s going to say “row this way.” It’s difficult to make value judgments about what’s happening. Sometimes you wonder why it’s taking so long to get to a change, but that’s part of the point with La Monte. As I said, you have to suspend judgment and say to yourself, “This is the way it is and I’m going to play the same way for the next 20 minutes as precisely as I can.” It’s not for the faint-hearted. You have to open up your mind and really engage with the dynamic.

What fascinates you about just intonation?

I took it for granted for most of my life that the standard 12 tones and the intervals between them were God-given. When I realized otherwise, it irritated the hell out of me. So, I jumped in full-force and started to hear the relationships of just intonation. I was very lucky to be introduced to it in a practical way by Jon Catler, who is an expert. I relieved myself of my ignorance little by little. If you play according to the harmonic series, your language expands a lot more. You hear relationships you haven’t heard before, but they’re not alien. What is alien is the use of logarithms to divide the octave into 12 equal parts.

If I sang just one note for you or played one note on any instrument, sympathetic vibrations are created which involve the harmonic series and partials. Those are what provide timbre or tone. You have a loud fundamental and less-loud partial intervals that provide character. So, when I play chords in which each note of the chord is based on just intonation intervals, it means the tones of the notes are all respecting the same tuning system, meaning the thing sounds good. Just intonation also expands your musical vocabulary. You have new relationships you can access. I’m able to play combinations which you can’t even simulate or imply on a 12-tone equal instrument.

Jon is very creative with just intonation. Together, we have done rock, jazz, minimalist, and symphonic works with it. We’re making real music out of it. We’ve even converted some rock standards like “Crosstown Traffic” into just intonation. It’s a world I love. Jon and I also have a band called Fretless Brothers focused entirely on just intonation. We play jazz and jazz-rock.

What’s your perspective on the state of the music industry as it relates to your output?

We used crowdfunding for the Gong Expresso album, which seems like a natural reaction to indie labels thrashing around for the last 20 years. It seems like an obvious outcome after everyone pretending to run record labels. There’s a kind of flea market element to the music business now, where you take a little bit of this and that, throw it all together and see what you can come up with in terms of getting your music out to people.

At this point in my career, I want to be able to get my music out to the people that care about it and get some feedback. I don’t have any illusions about fame or fortune. I don’t play music that’s popular in a large-scale sense. I’m not very good at doing business and there isn’t much business to be done, anyway. So, this direct-to-fan thing suits me fine.

I’m older now, sober and am lucky to have created good relationships with musicians, people who run studios, and other artists who all contribute. These are the things that give me pleasure. I don’t worry about if something is going to be successful at a monetary level. Certainly, there are thresholds you don’t want to go below, but life has left me able to freely float along. It’s a good place for me to be and I don’t resent it. There were times I had some self-pity about the situation. Now, I think that I’ve been lucky to have been able to make some good records in good studios with some good musicians.

If an album only sells a few thousand copies, I’m okay with that. It’s serious music made by serious musicians. The records are always recorded properly to audiophile standards. I care about that a lot. If I can realize good music and ensure the technical side is well taken care of then afterwards the conversation becomes only about achieving orders of scale. So, I consider myself very, very lucky.