Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Talking Heads

Remain in Sight

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1999 Anil Prasad.

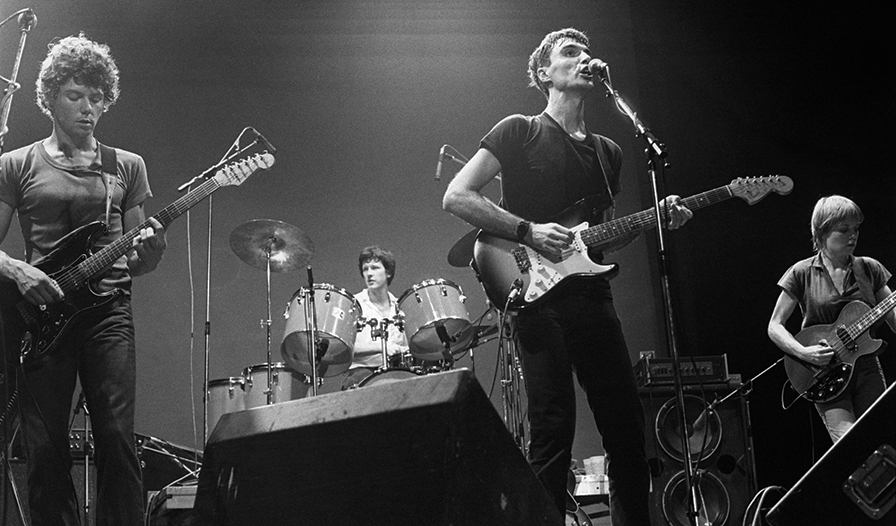

Talking Heads' 1983 live lineup: Alex Weir, Jerry Harrison, Bernie Worrell, Ednah Holt, David Byrne, Lynn Mabry, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, and Steve Scales

Talking Heads' 1983 live lineup: Alex Weir, Jerry Harrison, Bernie Worrell, Ednah Holt, David Byrne, Lynn Mabry, Tina Weymouth, Chris Frantz, and Steve Scales

It’s only minutes before Talking Heads are about to take the stage for the first time in nearly 12 years. It’s for a press conference to discuss the recently re-released Stop Making Sense, their landmark concert film from 1984. Admittedly, the event is little more than four people sitting behind a table nattering away about days long since past. But one would expect the excitement level amongst the lethargic throng of media types to be significantly higher. After all, this isn’t a reunion of just any run-of-the-mill act.

From the late ‘70s to late ‘80s, Talking Heads proved rock could possess an intellectual component and still remain viscerally engaging. The group was about eclecticism with a purpose, something Stop Making Sense exemplifies. The movie captured Talking Heads’ 1983 tour with an intimacy and flare rarely seen in concert films. The fact that the show itself was truly unique played a large role in that. It was a cunning production akin to visual Lego. Audiences literally saw a stage being built from the ground up, piece-by-piece as the music progressed. From the opening strains of David Byrne busking "Psycho Killer" solo with boombox backing to the full-on multimedia delirium that marks the denouement of the show, many filmgoers feel like they’re not only experiencing a remarkable event, but maybe even learning something in the process.

Given the importance of the film and band, the strange hush that hovers over today’s locale—San Francisco’s Dolby Labs—is a mystery. Perhaps the fact that it’s the world headquarters of noise reduction technology is responsible for the barely audible, low-key chatter with loungey piano music tinkling in the background.

Following a screening of the new version of the film featuring a stunning remixed Dolby Surround soundtrack and restored print, the quartet saunter to the front of the stage. Drummer Chris Frantz, guitarist Jerry Harrison and bassist Tina Weymouth are all dressed in black. Lead singer-songwriter David Byrne is wearing a cream colored jacket, accompanied by carefully-coifed spiky hair. They’re all friendly towards one another, although there’s an uncomfortable vibe in the initial interaction between the noir squad and cream-clad. But that’s not surprising.

Beyond the theatrical and DVD re-release of the film, what makes this event unique is that it occurs in the shadow of the severe acrimony that accompanied the split of Talking Heads. Byrne officially left the group in 1995, seven years after their last studio record Naked. Frantz, Weymouth and Harrison founded The Heads shortly thereafter and proceeded to record an album and tour using rotating lead vocalists. After catching wind of their plans, Byrne pursued legal action in order to prevent them from operating under the moniker. An out-of-court settlement resulted in which the trio effectively gave Byrne control over Talking Heads’ archival material in exchange for use of the name. The fact that The Heads’ debut record No Talking, Just Head was released with a large sticker proclaiming "This is not a new record from Talking Heads" pretty much sums it up.

Since the dissolution of Talking Heads, Byrne went on to an eclectic solo career and also founded his own label Luaka Bop. Harrison is in high demand as a record producer for the likes of Live, Rusted Root and Kenny Wayne Shepherd. Frantz and Weymouth continue making music with The Tom Tom Club, their groundbreaking pop-meets-hip hop group that's existed since 1981.

Innerviews sat down with Frantz, Harrison and Weymouth at the Miyako Hotel in San Francisco, the day after the press conference.

Does this gathering have any real meaning to you three beyond being a business obligation?

Tina: We loved that band!

Chris: It definitely holds real meaning. In fact, when I heard about it, I thought there’s no way I’m not going to go. That’s because for one reason or another, Tina and I didn’t come to the film festival in San Francisco 15 years ago for the original premiere. I thought, if they’re gonna go through all that trouble for the re-release, I’m gonna be there. I’m sure you felt the same way Jerry. [laughs]

Jerry: I live here! So, of course I’d be here. It wasn’t a big thing, personally.

Tina: You would have been here even it had been in Russia!

Jerry: I think we’re all really excited by the idea. I’m excited that my kids can come and see it now. We love this album and the film. It really did document a really important part of the band’s career. But to all of us, it was just one of the highlights. It wasn’t the highlight, but it was a spectacular one.

Tina: It’s not nostalgia to us, it’s now-stalgia. [laughs]

Chris: Now-stalgia! It’s like nostalgia for the present.

[everyone breaks into laughter]

The point I was trying to make is that after spending so much time trying to establish yourselves as The Heads, this might seem a bit of a regressive step.

Jerry: I suppose it could be looked at that way. But this is just a part of our history. So, no, this isn’t a regressive step. We made a new album together as The Heads. When we did, we weren’t trying to establish ourselves as a replacement for Talking Heads. But we thought it wasn’t right to rename ourselves in a way that no-one would have any idea of where we came from. The question was how do we logically make the connection without trying to appropriate Talking Heads? We kicked around the name "Shrunken Heads" which would have been more humorous. Stop Making Sense is part of where we come from. This is an acknowledgement of something great we did.

Tina: We think it’s terrible that people should demean at all what all those wonderful artists contributed to The Heads’ album. We think that they were great. It’s a wonderful record.

Jerry: Frankly, I kind of like every record I’ve made. I don’t have any problems with any record I’ve ever made. I can see why certain ones are more commercial than others, but every record I’ve produced, every record I’ve done—I like every one.

Chris: Same here Jer.

Tina: I’d say that’s true. Each one has its own special quality.

Jerry: See, this is artistic arrogance at work. [laughs]

Tina: Or else it’s because we’re parents of children. We look at them and we’re unbiased towards our own children. We see their merits when other people can’t.

Yesterday’s press conference had a sort of family reunion vibe for you three. There was a definite camaraderie. In contrast, Byrne seemed to be the quiet, distant cousin.

Tina: He’s always like that.

Jerry: It was really a deja vu thing.

Tina: That’s his whole persona. It was exactly like the old days.

Jerry: It’s not like we don’t understand the history of what went on. It’s not like there was an apprehension about it, but there was an enormous amount of "Here we go again…"

Tina: Same as it ever was. [laughs]

Jerry: It was "Let’s slip back into the moment of 1983." It could have been San Francisco, it could have been Italy. We’re being asked the same kinds of questions by journalists. People just ask us about rumors about this and that.

Tina: We really wanted to be here. It was also important to give kudos to the various people on the team, starting with Chris Blackwell. He puts out records no-one would touch today—people like Ernest Ranglin and Baaba Maal. Jordan Cronenweth isn’t here today because he’s gone, but his son Jeff is part of this project which is really cool. Eric Thorngren came into it again thanks to Jerry. So, we’d like to thank everyone. We wanted to be sure they get their kudos. We don’t just want this to be "I thought to do this and that and I accomplished it all."

Reflect on the collaborative effort between the band and Jonathan Demme.

Tina: Jonathan was a fan. He approached us and said "The way your show looks is so great. Why don’t you let me film it?" We said okay. He thought it was perfect for film in the way that it started with David and the boombox and builds. So it had a narrative quality built into it and he took it from there. He thought it was a very filmic show with beautiful lighting. I think he also liked hanging out with a rock band. [laughs] Jonathan went to every band member and asked them what they wanted. He was very respectful and that was kind of special. We found that very sensible, sweet and nice. Usually, they don’t do that. They do what they want to do. So, we said "We’re not crazy about split screen images and flashing images. There was always one camera straight on. The format was very flat. It was always like a painting—sort of like a Robert Wilson design in two dimensions, but also with four moving cameras. And even though there were cranes that would be observing things, a lot of the time we weren’t even aware we were being filmed. It comes across as being real.

Jerry: One of the big things we decided is that it was going to be just music and no interviews. I’ve seen so many music movies where I was disappointed when they cut away mid-song with people talking. They said it can’t sustain people’s interest to just have the music. We all believed that it could. Jonathan believed that it could too. I think it’s what set it apart from almost every other music movie. There’s no backstage footage or any other development. It’s just what it is. It makes it feel more like a concert.

Tina: One of the things about the new cut that’s different from many other films is that they put the audience applause in the side speakers, so you have a sense of being in the audience as you’re viewing it.

Why did you choose not to restore the three missing songs to the theatrical version of the film?

Jerry: We’re trying to be true to the way the film was. They are part of the DVD though.

Tina: It was about a year ago that we gave approval for the re-release. We carried on with our lives and projects and nobody gave us any further news. You have to be very careful with something like this. For instance, when the original video came out, a terrible thing happened. We were on tour and suddenly found out Warner Bros. had released the video without any quality control whatsoever. Nobody checked it. They took the quad mix and instead of mixing it down into stereo, they chucked out two whole channels. So, the first release of the video had half the sound missing which is totally weird.

Chris: It’s funny how things get lost. You think that because a record or film company takes it and puts it in a vault somewhere that it’s safe. Then that record company gets sold or merged with another record company and the vault gets moved from New Jersey to Philadelphia and then who knows what happens?

We’re almost down to one major label these days it seems.

Chris: Pretty much, yeah. Seagram’s.

Tina: Don’t they sell vodka?

Chris: Not the kind I like!

The DVD and CD re-release both contain the same stereo mix. However, the original CD’s mix was significantly different from the original film and video. Why did you choose to go with the alternate mixes originally?

Jerry: We wanted to enhance it for the album. We thought it would be nice for it to be different and separate. It was largely what we played with additional effects. It’s not like we re-played it all.

Tina: Well, we re-played some—the stuff that had buzzes on it.

Jerry: I know, but that was for the movie and the album. That was fixing things with technical flaws, but we didn’t redo stuff for the album.

Chris: The feeling at the time was that if we wanted to get it played on the radio—which we did—the album had to meet the production values of the time that radio was insisting on. Therefore, there was a lot more time spent on the album mix than there was on the film soundtrack. But this time, the same guy went back and remixed the sound for both the film and CD re-release.

Tina: That was very cost-efficient. At first they didn’t want to do that, but Jerry convinced them. You have to talk to these film makers like they’re Republicans and say "Hey, it’s gonna save you money!" So, yeah, everything is redone for the CD.

How involved were you all with the creation of the new mix?

Tina: All we had to do is approve it.

Chris: We were involved as far as whether or not we liked it. In other words, it wouldn’t have come out if we didn’t approve it, but we weren’t doing it.

Tina: We didn’t have to be involved, but we went to visit occasionally. We were dealing with very professional people and trusted them.

What goes through your mind when you watch your 1984-era stage persona on screen?

Jerry: I think I get a little annoyed by it.

Tina: Me too.

Jerry: I look at it and go "Oh God, that’s stupid."

Tina: I see all those stupid, arrogant mincing moves.

Jerry: I cringe at all of the flaws.

Tina: It’s creepy isn’t it?

Any flaws in particular?

Jerry: I’m not gonna say what they are. It’s subtle.

Chris: Your nose is too big? Your hair’s not right? What is it Jer? Come on.

Jerry: It was "Oh God, I could have done that dance better" or "That was a bad night for that." I do like the solos I played that night a lot though.

Tina: We all got the playing to our satisfaction, but as far as how we look, that’s another thing. We’re not actors. We were creating something fresh in the moment. We never saw ourselves until the movie came out. It was kind of a shock. But David studied himself very thoroughly. He had this little set-up in his loft where he had a TV and a full-length mirror. He would rent movies like The Royal Wedding with Fred Astaire. It had a routine called "I left my hat in Haiti." David would practice the dragging the foot thing which he ended up doing with the big suit. [she gets up and starts mimicking Byrne’s big suit moves] All of those moves are from Fred Astaire. Everything is borrowed. David is really like that. That’s who he is. He doesn’t go with things the way we do. He’s a different kind of creature altogether. So, we tended to have all of the human flaws which felt a lot cooler than they look. [laughs] We had that sort of white man’s nerd disease happening. Some of my dance moves which I imagined were very avant-garde now look so corny, dated and uncool. I wish I had stayed the way I was and hadn’t tried so hard.

Is that what happened during filming? You were portraying someone you really weren’t for effect?

Tina: I think I was trying. I was actually trying to connect with the audience.

Chris: Hell yeah! You weren’t just trying—you were connecting with the audience. Jesus.

Tina: We were once removed though.

Jerry: I know I looked really tired the night we filmed. I had been up the whole night before and then got up really early. I got into a big argument with our lawyer about the movie. He wanted someone from the band to back him up on something, so I went to this meeting. I thought I’d take a nap after, but then I got nervous and never got back to sleep. That happened to be the night the camera was on my side and I thought it was the worst performance of all three nights as far as how I looked. I had to really, really force myself to act because I was really tired. So, whenever I watch the film, I have to literally kick myself and ask "How could you have allowed yourself to go that meeting?" But they said they needed me, so of course I went.

Tina: But that’s also vanity to be so concerned about how you look.

Jerry: But he was asking me what it was like!

Tina: It’s awkward. It’s like when you hear your voice on a tape recorder and say "That’s what I sound like?" So, it’s like "Ooh, so that’s what I really look like." My face I don’t mind it, for I am behind it, but it is the people in front that I jar. But if you look at the people you love—people like Steve Scales and Bernie Worrell—did it capture those people correctly? I say yes. And then you say, "Why is the camera on Alex Weir dancing when Bernie is in the middle of a Clavinet solo?"

Jerry: We helped correct that as far as being involved in the editing went. It was usually that kind of comment: "You’re missing what’s happening musically at this point."

Tina: Only God is perfect. It ends up being a film exactly like a Turkish rug. Everything is perfect except for one little mistake because you know only God is perfect.

Chris, you had a particularly unique viewpoint being perched up top with a 180-degree view of the audience and the band. Compare your perspective to that of the film.

Chris: It’s very different in that you have a lot of lights in your eyes. It’s hard to see beyond the first or second row. Sometimes you can see if they shine a light out into the audience, but mostly, the audience is in the dark. Also, the sound is being projected forward and not back towards me. So, when I go "boom!" it becomes "BOOM!" out there. But it’s "bap!" where I am.

Tina: I always thought Chris was the puppeteer of the group. He’s in the back smiling and controlling the rest of us in the front line. We’re attached to the strings and he’s egging us on. He’s such a great drummer.

Chris: Aww, well thank you. [laughs]

Tina: He’s so rock steady and he just moves you. I remember once when I took Robin [her son]—who was a baby only nine months old—to a show. It was the encore and our nanny said he can’t sleep. So, I took him out on stage on my back. It was during a song in which I was playing keyboard bass. He didn’t pay any attention to the band in the front line. All he was interested in was watching Steve Scales to my left and his dad on the right. It was all about drums. This baby was totally into that. That’s what he connected to first and foremost. It took him a long time to find out "Oh yeah, there’s this guy up at the front singing."

Chris: Being a drummer gives you an interesting point of view. I could see everybody in the band and that was nice. I wasn’t on the end where I couldn’t see Bernie on the other end.

Tina: It’s a great vantage point.

Chris: I don’t feel particularly self-conscious when I look at the film, but I remember being highly self-conscious when it was actually going on. I had to be very careful about the tempo. And you couldn’t look at the camera. You’d be playing and suddenly look over at Bernie and there’d be this camera in your face and you’d freak because they just told you "don’t look at it." Today, I’m just less self-conscious about being onstage. I’m much more relaxed about it.

Earlier, you mentioned that Stop Making Sense was just one of the highlights of the band. What were some of the others?

Jerry: My favorite records are Fear of Music and Remain in Light. Fear of Music completed the earlier vision of the band, yet had a sophistication about it. Remain in Light was the beginning of a new vision. It was a very creative period and really amazing.

Chris: I enjoyed the whole experience, from the three piece band getting started, living on the Bowery, playing rock and roll music, meeting Lou Reed, Patti Smith and the guys in Television. Then there was the period when we got to go to Europe as the support act for the Ramones. That was my first trip to Europe and the greatest way to see it. It was really amazing. It was the early days before the Sex Pistols, but only just. They were just getting their thing together. All over Europe, there was a big interest in underground New York rock music which we were one of the representatives of. That was pretty cool. Then there was the first time we came to California. That was pretty exciting. That was after we’d been to Europe. It was funny. We could play Europe in big, rather good-size concert halls before we could even get a gig in New Jersey. Then there was traveling across America with the big band. Things jumped up quite a few notches in terms of the excitement level all around us.

Jerry: There’s always something about the very beginning when you remember your history as a musician. It goes beyond this band and you go back to something you did in high school. The craziest and funniest things are the smallest clubs—the pizza parlors, not the more boring and generic civic centers. The more successful you get, the more you’re tortured by these generic auditoriums that are 30 miles out of town.

Tina: The beginning was the best because there were no barriers between us and the audience. There was no media, so nobody knew who we were. That was very pleasant. People would just meet us and say "Hey, do you want to go take a hot tub?" [laughs] Or some really gorgeous girl would come up to Chris and say "I’ve got three Quaaludes. One for you, one for me and one for Tina!" Whatever! [laughs]

Jerry: I think when we began playing, there was an intelligence in the audience. You felt like "I’d hang out with any of these people." When we played with the Ramones, we’d just wander and someone would come and find us and say "Do you want to come out for coffee?"

Tina: You still get that in places like Austin, Texas. People still come through and offer you mushrooms or say "I remember when you used to baby-sit for my friend."

A new Heads album was scheduled for early 1998 but never materialized. What happened?

Tina: Yeah, we did that, but just like everyone else on MCA, we’re on hold. [as a result of Seagram’s taking over the label]

Chris: We’ve been concentrating more on the Tom Tom Club lately. We just came from Compass Point studios in the Bahamas where we’ve done a lot of work in the past. We got together with the engineer Steven Stanley from Jamaica who did the first, second and fourth Tom Tom Club albums. He also engineered "Once in a lifetime" from Remain In Light. We’ve mixed four new songs. The idea was that some new stuff would go onto a greatest hits compilation.

Tina: In order to give closure to that retrospective.

Chris: But then the record company said "We don’t want any new stuff. We’re just gonna put out the old stuff." So now, we’re shopping for a deal for some new stuff. It’s all up in the air. We’ll see how it goes.

How difficult is it for you to shop new Tom Tom Club material in this climate?

Chris: It’s not easy.

Even with your stature?

Tina: What stature?

Chris: We’ve got some stature today because of this event, but I don’t know about a week from now.

Tina: You get your 15 minutes and that’s it.

Chris: Let me put it this way: We had to make sure we came up with some really good stuff in order to get people interested. It’s not like it was 15 years ago.

Tina: You can’t be experimental. You have to fit a format.

Chris: Everything is, shall we say, more businesslike.

Tina: We have to have product. [sarcastically]

Things like Talking Heads and Mariah Carey using "Genius of Love" don’t give you any cachet?

Chris: It’s really good at the music publishing house. It gives you a lot of cachet with ASCAP, but not with the president of Universal, Warner Bros. or Reprise.

Tina: We have such a difficult situation because we spearheaded new wave and alternative music, as well as hip hop. People are very confused about where we stand.

Describe how the Tom Tom Club spearheaded hip hop.

Tina: Chris played on "These Are the Breaks" by Kurtis Blow.

Chris: We were right there when it happened. "Genius of Love" was one of the early hip hop classics. It came out before "The Message."

Tina: It came out after "Rapper’s Delight" but before "The Message" and "It’s Nasty." It’s an ‘80s song about cocaine that came out before "White Lines." Our problem is we’re a totally integrated band. You’d think that wouldn’t be a problem today. You’d think that what the founding fathers wrote down 200 years ago would be set in place. But no! Everyone has to have a very long memory and remember every little thing that happened and every thing that didn’t happen. So, it’s a very difficult problem. We can’t play with Public Enemy because people would be throwing things at us like we’re black sheep. But, we can’t play with Dave Matthews either. We have to find other ways to get in. We have to be with people like A Tribe Called Quest. But what happened to them? Same thing as us. They fell between the cracks. Or look at Prince. He had such a difficult time getting over into the white rock arena.

We’ll play the same venue as Queen Latifah will play, but it won’t be the same audience. How do you get people to understand that you’re coming from the same place? How do you get the white kids in the suburbs to understand that you’re hardcore too? All week, I was picking the brain of the promotions and A&R guy from Death Row—Daryl Young. He’s a very intelligent man. It was fascinating to talk with him because he’s 40 years old. He talks like our manager and agent used to when they were pioneers. But they’re all so stuck because they know what’s there at the top: a brick wall that you can’t get through—the CPAs and lawyers. People ask "Why are you so concerned about the bean counters?" Because the bean counters are looking at Soundscan. Meanwhile, [record company executives] know what to do. [They’ll] have a relationship with all these mom and pop stores that report to Soundscan. [They’ll] guarantee them "I’m going to buy 200 CDs from you" to make sure Soundscan is pumped up before the hype begins.

Is there any support from contemporary artists for what you do?

Tina: I was doing what Lauren Hill was doing 20 years ago, but I can’t ride on her coattails because she’s not going to talk about me. I’m not bitter towards Lauren Hill. She’s a young girl who doesn’t know. I’m not bitter towards the industry either because it’s just business. It’s not personal. Our job is to figure out how to work it. There’s something going on here that’s going to be very transitional. There is this thing: gangsta rap. Gangsta rap is no joke. It really is gangsters. It’s just like the old mafia. You owe people and you have to pay. It’s very hard for an artist. We’re people who own our own publishing. You think Death Row is gonna give us our publishing? Are you kidding? You think Suge Knight is gonna sign us without taking at least the lion’s share, if not all of it? No way. We know the score. We’re not young artists. So "Hey, goodbye!" That’s the way it works. If you know too much, it works against you. If you know too little, it’ll work against you down the road. So, we have to figure out how to work it for ourselves. We can’t feel sorry for ourselves—not at all. This is just the way it is.

What’s good is sometimes you can do some good. For instance, thank God we built our own studio eight years ago. It doesn’t matter that these people are all screwed up. We don’t have to wait for them to book us into a studio. We just work. When they’re ready, fine, no problem. Meanwhile, we can help people who are extremely important to us like our friend Abdou Mboup. He played on the Talking Heads’ Naked record. We met him in 1987. He’s a griot from Senegal and is playing with Manu Dibango. He’s an amazing guy and he’s trying to get a green card to live here. How do we convince immigration that this man is valuable to our country? It’s not easy. They’ll take someone from Puerto Rico who picks berries over someone who is an educated teacher and historian. So, our job is twofold. We have to take care of ourselves or we haven’t got anything. And we have to take care of the other artists around us because without them, we’re nothing. So it’s a challenge to understand how the business and politics work.

Who is releasing the Tom Tom Club compilation?

Chris: Rhino.

Tina: They insist on it.

Chris: We were signed to Reprise. But Reprise has a deal with Rhino in that any old catalog gets distributed by them. We hoped it would be on Reprise, but instead it’s going to be on Rhino. Rhino doesn’t have the budget to pay for some new material.

Tina: They can’t even put it on radio. They won’t promote it.

Chris: They don’t have a promotion budget.

Tina: What they want is easy money. They want catalog. Just put it out and see what it does. Don’t put any money into it. Don’t put any effort into it.

Chris: They put some effort into it. Rhino is okay. The problem is the people at Reprise jerked us around for six months, so now we have to scramble. There are some other people interested—particularly in the U.K.—and ready to make a deal. We always broke in the U.K. first anyway, so maybe we’ll do something over there and it’ll have repercussions over here. It remains to be seen.

Tina: Never look over your shoulder.

Have you thought about going totally indie for future Tom Tom Club projects?

Tina: Exactly.

Chris: We have.

Tina: Once we’re free of obligations, that is a very real possibility and we’re very excited about it. We want to be able to do things like create and organize our own package tours. Say, us, Bernie Worrell and the Woo Warriors and Deep Banana Blackout—an integrated band that is very P-Funk and James Brown-influenced. There’s a roots underground thing happening with kids—a funk thing. The record industry is focused on "Let’s make money now and sell some jeans and some cola. Let’s resell it as counterculture material." We want to try and sidestep that whole thing like these other groups like Phish have done. We want to forget about all the bullshit.

How were Talking Heads able to make the industry work for them?

Tina: The record companies really didn’t tell us what to do after the first record because they knew it would be hopeless.

Jerry: We very much determined our course. A lot of that had to do with the fact that our sales were growing slowly. We never asked for any money. If we went on tour, we would always make money because we would always keep our production at the level we could afford. We didn’t ask for anything. We just said "Put our record out." We determined our relationship with the record company, largely because we weren’t attempting to have a huge hit. We weren’t going after what everyone else wanted, which was to sell as many record as possible as soon as possible. Because of that and because we were able to grow, they would say "It’s doing better. Great. Keep going." It allowed us to have that control.

Chris: A lot of people don’t realize that the band put up the money for Stop Making Sense too.

Tina: Our manager was already a promoter and knew the ins and outs. The promoters would never put the Talking Heads up, so he would promote the show himself.

Jerry: He would go to clubs that play top-40 bands and go "It’s Thursday night. What do you think about me bringing this band in? You guarantee them $200, but we get this percentage at the door." The promoter would go "That’s a great deal. The top-40 band costs $600." And the audience would grow. Devo, the Police and these other people followed us around the country on this path. We took Chris’ father’s station wagon and drove places. We’d go "Let’s drive to Buffalo today and then drive back to New York." It was our willingness to put ourselves through that.

So, what changed to make the industry so unhealthy?

Tina: It’s unfortunate. The record business used to be a great business, but people got really greedy. They’re not happy charging $8 or $10 anymore. Now, they want to charge $50 for a concert. Excuse me, if Lenny Kravitz or Madonna charges $50 for a show, then it’s gonna be another month before the kid who spent $50 sees another show. And if they’re on a date with hamburgers and gas, that’s more than $100! And what’s out there to see anyway? Paul Simon? Elton John? Bruce Springsteen? The Eagles?

Chris: Don’t forget Aerosmith!

Tina: It’s terrible for bands today. Just terrible. There are clubs now that make the band pay to play.

Jerry: You have to guarantee a certain number of people will be there. You can resell the tickets.

Chris: If you’re young and have the attitude that you can conquer the world and don’t mind sleeping in a van or on your friend’s couch or floor and are willing to be very spartan about it, then you can do it. It’s very expensive to tour nowadays. It was always kind of hard to make ends meet on the road. Now, to meet people’s expectations from a production point of view—really good sound, lights and visuals—you need a sponsor or tour support from a record company and that’s become harder and harder to get. We have a lot of friends who have very interesting bands, but it’s hard for them to tour the state much less the whole country without someone kicking in. There is also the problem of people seeing the band’s video on MTV.

Jerry: It’s easy for them to be disappointed when the production values of the show aren’t up to what the video is.

Tina: And some bands only make it on the strength of the video because they look so good. The studio album is fixed up to make them sound good and they are a disappointment live—they can’t play. They are a concoction. It is a problem, but you can’t be defeated by it. And it’s hard for bands nowadays to make films now because they have to spend all the money on videos. I think Stop Making Sense cost us what it would cost us to make a video now.

Chris: Maybe less.

Tina: What we have to believe is that there is very good quality music out there that is completely integrated and doesn’t follow some stupid format. We’re so fed up with that. And then see what happens to kids who have to play it to the hilt like Tupac. We cry for them. Maybe it’s true that this was Tupac’s destiny—like Bonnie and Clyde. Maybe he wanted that way to go. He was a smart kid, but he didn’t see the whole thing. He didn’t see the forest for the trees. Why some 24-year-old kid is dead who had that much talent… it’s criminal. Just so some record company could get rich off him? It’s sad. He could have gone on to many wonderful things like John Lee Hooker, James Brown and B.B. King who are still at the front doing things. I saw Muddy Waters perform when he was 80 years old. It was criminal then because [African-American artists of Waters’ generation] were dying because they didn’t have their publishing. They had to keep touring in order to live. They lived hand-to-mouth. Thank God, we got to see them. Anyway, it’s very much more complicated than what we see. We think we understand it and it turns out to be the tip of the iceberg. It’s like a cancer and it basically comes down to greed. And now they’re all scurrying and worried as hell about the Internet. It’s very interesting to see them all so damn scared. But a lot of possibilities do remain.

Chris: Tina, stop making sense.

All photos courtesy of Sire Records.