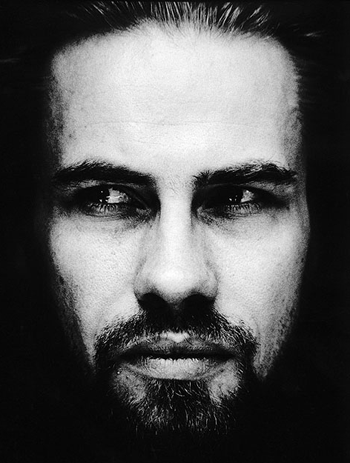

Jonas Hellborg

Grids of Reality

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2001 Anil Prasad.

There are few absolutes for Swedish bassist and composer Jonas Hellborg. Points of influence, origin, classification and credit are concepts he prefers to leave to others. He's adopted a set of personal and musical philosophies focused on intent and interaction in the moment, rather than postmortem analysis. The open-ended approach embraces free-spirited exploration and improvisation—something exemplified by his latest release Good People in Times of Evil.

The trio disc finds Hellborg, guitarist Shawn Lane and Indian percussion master V. Selvaganesh engaging in exhilarating musical dialogues. Together, the three forge an amalgam combining jazz and Indian classical music. Previously, the trio worked together during the 2000 Zen House tour, supporting an album of the same name focused on acoustic pieces modeled on Indian raga precepts.

Hellborg's made a career of ignoring decrees of demarcation since first hitting the jazz scene in the early '80s. It's a penchant that manifests itself in his choice of material, gigs and technique. His innovative basswork, straddling chordal, percussive and melodic leanings, has been featured in a wide array of contexts.

Between 1983 and 1988, Hellborg was part of Mahavishnu, a reconstituted, updated version of John McLaughlin's pioneering '70s fusion band Mahavishnu Orchestra. During that period, Hellborg also worked with McLaughlin in a variety of duo and trio formats featuring drummers Billy Cobham and Trilok Gurtu.

During the early '90s, Hellborg collaborated with Bill Laswell on several recordings for the Axiom label, including The Word, a solo effort featuring drummer Tony Williams and a string quartet. The duo also worked together on Material's boundary-breaking Hallucination Engine, Ginger Baker's thunderous Middle Passage, and two experimental funk releases by Deadline titled Dissident and Down by Law.

But it's Hellborg's releases on his own Bardo and Day Eight labels that truly showcase his gifts. The labels comprise the bulk of his solo output and find him immersed in a multitude of acoustic and electric environments. Solo bass releases, duo efforts with frame drummer Glen Velez, and trios featuring the likes of guitarists Shawn Lane and Buckethead, and drummers Michael Shrieve and Apt. Q-258, are just a few of the labels' highlights.

Based in Paris, Hellborg discussed the philosophies, challenges and rewards of making Good People in Times of Evil with Innerviews. He also provided a thorough look at his broader viewpoints on the muse and the role of music through the ages. During the interview, Hellborg spoke in a resolute, confident tone. Clearly, he's a man content with his perspectives and unafraid of engendering debate.

Tell me about the title Good People in Times of Evil.

Originally, I got the title from a book written by the granddaughter of Marshall Tito of Yugoslavia. Tito was the guy who pulled Yugoslavia together and united the different peoples into one coherent country. As long as he was alive, Yugoslavia functioned as a nation. His granddaughter is a Serb, mainly, but a mix. She was in Bosnia during the first troublesome uprising period of revolution and civil war. There were many reports in the media about how terrible the Serbs and Croats were. But in the midst of this, there were Serbs who did astonishing things to save Bosnian people from eradication and torture. She collected these stories in a book. The concept is very interesting. We have a tendency to generalize everything. As soon as something bad happens, you get the view that all Germans are Nazis or all Serbs are terrible. The book is a reaction to this kind of black and white mentality we have. We can't see the gray scale or the entire structure of things.

Describe your attraction to Indian music.

It goes back to my teenage years of being a hippie. In the late '60s and early '70s, everyone was into Indian music such as the Beatles with Ravi Shankar, and the Mahavishnu Orchestra with John McLaughlin. When I started playing seriously, I was into John McLaughlin. I started playing with him and meeting all these great Indian people. So, it's been an ongoing thing for me during my whole career. The first thing that’s obvious for a Westerner is the rhythmic complexity of the music. That was my first attraction and fascination—the method, teaching, composing and understanding of rhythms. What also really struck me was the melodic aspect of the music, as well as the intricacies, ornamentation and variations.

What challenges do you face adapting to the world of Indian music?

There are definitely challenges. If you're born into something and grow up with it from childhood, not to mention engrained in the overall culture, it's much easier to comprehend, understand and assimilate all the aspects of it. But as an adult, coming into it and studying as an outsider means you'll be limited in what you can grasp. I'm not pretending to be Indian by any means. It's like going to an Indian restaurant. I don't pretend to really understand the food, I just like to eat it. With music, I understand enough to play with Indian musicians and get a bit of what's going on and that makes me happy. That's basically it.

How do you balance Indian music's rhythmic complexity steeped in mathematic equations with the more chaos-laden, less studied leanings of jazz improvisation?

I look at it this way: the world consists of chaos and the human being is endowed with a talent for seeing structure in chaos. It's not that we create any kind of structure or order. We have ways of creating reality and finding something that looks like logic. By it being that way, you can apply different sets of logic to the same reality and get two different results describing the same thing. If you have a system of perception, you can actually make sense of something. It doesn't matter if your sense of it is the same as someone else's. What matters is that you are describing the same thing. Then the same realities can go together.

By that logic, all music is mathematical because there is some kind of absolute truth in numbers, vibration and how that translates to all phenomena. We know that from light to sound to time cycles to basic substructures of the atom that a mathematic solution can be ascribed to everything. That goes for music too—even total chaos music. It's just a different level of the grid you're using to understand what you're doing and what aspect of music is important to you—what aspect of the execution you pay most attention to. So, you can think about the Indian way of looking at rhythm and analyze any piece of music and find the structures of logic. If something is attractive in a musical sense, it has some kind of built-in logic that you have to discover and explain to yourself. It doesn't mean that's the way it was born or created from the beginning. I really think great musical creations are not structurally created. They are just intuition. They come in a flash, but you can apply logic and understanding to them.

What made you want to work with Selvaganesh?

Selvaganesh is a case similar to Shawn [Lane]. I've known about Selvaganesh for a long time and tried to make contact with him previously. It was totally impossible. I had no way of doing it. Then he came here to Paris a couple of years ago with Zakir [Hussain] and Vikku [Vinayakram]. I was introduced to him and he knew about me. I asked him if he wanted to do something and that was it. He's extraordinary. I think after Zakir and Vikku, he is the Indian percussionist and might be surpassing them at this point. He's more modern, open and aware of stuff that goes on at a different level than any of the older guys.

Why do you think that's so?

It's a generational thing. If you grew up with the media boom and MTV revolution, you'll have a different outlook on life than if you lived in the old communications world, so to speak. If you're exposed to more stuff, you have a different view. It's that simple.

You once said "the art of listening is a rare commodity amongst musicians." Elaborate on that.

Music is an aural art form. It's about the sound. The way we perceive the logic of music is through hearing and listening. It doesn't matter how we produce the sounds. Sound is simply the world we need to inhabit in music. It doesn't matter how I produce a sound on my instrument, or what technique or fingering I'm using. If I concentrate on those things, then it's not music, rather it's some kind of sport. But if I stay in the realm of hearing the sounds I'm producing, it's that which determines the music. The time factor in hearing and experiencing music as sound is really what should create the music and reaction. So, it's not the logical structure of elements, but it's actually a spiritual experience in sound that really is the music.

Man's behavior is very mechanical. We don't really pay attention to what actually goes on around us. We're more reacting to references. References trigger some kind of stored memory that we immediately just call up to predefine any experience we have. So, one does not actually pay attention to the experience. The same goes for music. If you hear a saxophone, you go "jazz" and you recognize the outline of what's going on without really paying attention, although you hear it. As a result, you can function socially with that element—you recognize the basic structures and it sounds fine and dandy, but 100 percent listening rarely happens. If people would really listen, music would develop and we wouldn't have so many retro movements going on.

America's jazz scene seems particularly mired in retro tendencies. Any thoughts on potential solutions?

I don't think it's something you can solve because it is like everything else—a picture of society and reality today, just as the original jazz was a reaction to society when it happened. It's sad in a sense in that the people who really did create that music didn't really get any credit with the exception of a few icons. Now we have people who study that music in college and make really bland carbon copies of the stuff when it was real. They get credit, become super-famous, make tons of money, and have a position in society. But that's a human societal structure. It's just how it is. It doesn't have much to do with music. This stuff has been going on with classical music for hundreds of years.

I think that music has to find its own way. Music has to fill a function in a societal reality. It's got to mean something for people. It's got to be as obvious as the clothes we wear. There has to be a reason for music to exist and develop. But music has been so commercialized as a commodity that is oversold. There's so much of it that people lose the need for it. People never get to starve for music. Think of the situation before recording mediums came out. Go back to Germany 200 or 300 years ago when somebody great had written a new piece of music that required you to go to that concert—that was the only chance to hear that piece of music. If you didn't listen at that point, you might not get another chance because it was too cumbersome and expensive to bring the orchestra or ensemble everywhere. So, the intensity of the experience of going to the concert and really listening must have been really incredible. You had to be really aware. You couldn't just put on a CD and listen to it anytime you want or choose from 30 different concerts a day going on in a big city.

You tend to include sparse, basic information in your liner notes, yet your website offers very in-depth essays and philosophical thoughts relating to each album. Why not include them with the CDs?

I think it is a matter of identity. I am somebody and I look at myself in a certain way. Music is something that is sort of outside of me. What I do musically is an expression, but it's not necessarily me. So, the relationship people want to have with my music is something I should not be influencing too much. On the other hand, if people want to know how I see it, what inspired me, why I did certain things and my reasoning, I'm not against sharing that either. I just don't want to push it down people's throats. I think it's better to have the music as a statement or indication and people can have whatever relationship they want with that. If they want more, they can go to the website.

Is there a particular set of philosophical perspectives or writers you look to for inspiration?

Not really. There are lots of great people through history who have written lots of great stuff. Some people have said good things and bad things. I don't believe in individualism. I don't believe anyone ever creates anything. It's all a collective movement. We all get inspired and nudged by everybody else's effort. To claim ownership of an idea that you created or invented is really preposterous in a sense. I like the essence of an idea. I don't care who it comes from or their name. Some people do build up huge bodies of interesting work and this body of work is identified by the name of the creator. This is fine also. It's a structural thing created so you know where to look for stuff. But I think life is in and of itself enough. You reflect on life and get inspired to express certain things, even though everything I say is not coming from me. Really, it's coming from reactions to everybody and everything.

Describe the philosophy behind your idea that "music isn't important, it's just a language."

What we do as people is important, but music itself doesn't contain any of that information. It's like speaking French, Greek, Swedish or Albanian—it's just a vehicle for communicating something that is hopefully already there. If it's not, it doesn’t matter how many words you use. It's just a waste of sound in a sense. In order to play any kind of music, you have to have something to say. You have to have lived and experienced a life and have something to express as a result. Otherwise, it's meaningless and pointless. That's why a lot of the retro stuff is totally uninteresting. It's like the musicians reading text they don't understand. They're just saying the words and don't have any relationship to what they're saying. That goes for a lot of the jazz stuff where they have learned vocabulary that people created in utter misery, drug addiction, abuse and really bad living. But now these musicians have studied it in college and learned how to play it, but it doesn’t mean anything anymore.

You've spoken of a spiritual element that informs your music. What can you tell me about it?

You can't be human without the spiritual element. That's part of what we are. In a certain type of definition, it has to do with what kind of grid you put on reality in order to explain it. We are beings that exist on many different planes and levels. We have a purely instinctual side, an emotional side and an intellectual side. We can find many different terms to identify certain aspects of our natures. One very popular way is saying it is spirituality, which I guess has to do with religion. But it's not something that's necessarily intellectual in describing absolute reality as we experience it. It's very hard to put into words as there is a mystic element to it. If you enter music, there is something magical and mystical about it that goes beyond the things we can explain like pictures, time and dynamics. There are things that go into sensations. It's like being in another world, like taking drugs almost. What is that if not spiritual? Even if it's the most profane, arcane kind of music or really simplistic, it's spiritual. Even country and western music, which normally isn't considered spiritual, is. If you think about it, people are into that experience. And when they are part of that ritual, it is a spiritual ritual in a sense.

Are there any particular spiritual traditions that interest you?

There are so many. The problem is when you start to fence things into a certain territory or identity. You have the Buddhists here, Hindus there, Christianity there and you exclude instead of include. The exclusion is the danger because they're all ways of seeing the world as it develops and as we change. It's not necessarily a development, because we just change as times change and see things differently. It's all interpretation. Nothing is really true in the sense of our verbal understanding of the word. It's just a description, not reality. The reality and experience are true, but the words we use to describe that reality cannot be true. They are dependent on definition. No two people understand the same word exactly the same way, so how can anything written be an absolute truth? It's an impossibility.

In your Ars Moriende essay, you wrote "killing ourselves and each other symbolically would maybe be a refreshing idea." What did you mean by that?

I wrote that during a period when I was very much into understanding the concept of death. I was reading a lot about death in different ways, including the mythological aspect of it. I was very much helped by Joseph Campbell, who has written many great books on mythology and related subjects. Death is a huge subject to even touch on. Death is dependent on the creation of an identity or image of identity. This has a lot to do with the music world, mainly on the business and commodity side. You create these icons which are not necessarily the people who inhabit them. There are these other identities—roles that people who create music go after in order to play out in front of the world. You create this and then you kill him before he's even dead, and when he dies for real, he's still alive because he's kept alive by all the fans and the world as an iconical figure. So, who is that? Is Elvis that? Is Elvis alive? What does it mean? And if you do something in a certain aspect of yourself or within a certain identity, maybe it's not such a bad idea after you've finished the work to kill that identity of yourself and be born again as a new person. This goes back to the tradition of regicide in old cultures. Often, they appointed a king and he was to be there for seven years. After that, they would kill the king and his whole court—a big ritual slaughtering. Then a new king would be appointed. This goes on a lot in music because the public creates these great stars, keeps them for awhile and then kills them off. They think "This person isn't popular anymore, so let's forget about him. He's old. Let's kill him and appoint a new king."

How are you able to function from a philosophical perspective within this system?

I haven't really been part of the music business in a sense—or at least, only in a very limited way. I see myself as a collector of experiences. I want to try different things in life and play with different people. These things result in concerts and records and that's the way I make my living. I guess I have taken on different identities through time, because that's the way you can experience it. Experience makes us into a certain well-defined person. That changes over time and with what I do. But I've never had great commercial success ever. It's not something I regret or something I would be opposed to either, but it's just not very important.

Since the beginning of your solo career, you've released most of your records independently. What made you pursue that approach from the outset?

Yes, from the very beginning everything has been on Day Eight. I also did a record for Bill Laswell on Axiom and a few other things for other labels. I saw pretty early what was going on with the so-called business of music. People were getting enslaved both mentally and in the more material sense by their aspirations to become this or that or by contracts and financial means. All of that really did not interest me too much. When I was really young and first started, it was fun to play on huge stages, be recognized and appear on the covers of magazines. It was an ego boost. You're somewhat of an exhibitionist if you want to be a musician to begin with. It comes with the territory. As soon as I started experiencing those things, I was to a large extent cured of it. I wanted to go on and see what life had to offer. So, it was very simple. Certain things had to be taken care of. This is the simplest and least challenging way of doing things in terms of releasing a record. It's basically down to you. You need a studio, people to play with and then you produce a tape. If somebody wants to buy it, you need a means of distribution. I had to figure out how to organize that structure, but it's always worked. I never had any incentive to be in any other situation.

Your first two albums, Bassic Thing [1982] and All Our Steps [1983] are out of print. Do you plan on reissuing them?

No. They came out over 20 years ago with 1,000 copies pressed on vinyl. They are out of print and don't exist anymore. Of course, now that they aren't available, people talk about them. But they're no good. I promise you wouldn't want to hear them. [laughs]

How do you look back on your time with Mahavishnu?

The whole experience was pretty ridiculous to me. Mahavishnu was a typical thing caught up in the wrong desires. The whole group never really wanted to happen. It was a forced endeavor. We never really created any kind of togetherness or music. I don't really consider that any kind of high point in my career except that it gave me lots of recognition, which is kind of ironic in a sense. I don't think that stuff is too great. However, I did like doing duets with John McLaughlin that were never recorded. The two of us did lots of concerts as a duo. That was pretty good—very simple and unpretentious, just some music performed together on acoustic guitar and electric bass and that was it.

As for Mahavishnu, it was something else entirely, but the original idea was pretty good. The original idea was to have Billy Cobham, Michael Brecker, Katia Lebeque, John McLaughlin and me. John had written some very interesting music that never got recorded. And Katia is not an improviser, so it was written stuff. It was sort of the direction of John's album Belo Horizonte, but a little heavier and more together. At that time, Billy Cobham was still an interesting drummer. We had some rehearsals that were pretty good. The first thing we did together was in Rio with me, John and Billy on French television. That was really good too. It was the same thing, not really pretentious—a few songs that we played straight, very naturally and simple. It was good music.

Given the music had practically no relationship to the original Mahavishnu Orchestra, what made McLaughlin adopt the truncated name for the new group?

Money. [laughs] It was "Let's re-launch the career and let's relive the past." That's what it was about originally. He wanted to reform the group and he went to Jan Hammer and Jerry Goodman and they all asked him to take a flying fucking rolling donut. [laughs] The only one who was interested because he also realized the potential of the career boost was Billy Cobham. Being the great materialists, they couldn't hold it together and started fighting. The incentive was very cynical. It was only about having a better career, not about music at all.

Many have described Zen House as being influenced by Shakti. Is that a legitimate observation?

Of course there is some relationship. I am very, very much inspired by that group. I think Shakti was one of the greatest groups of the '70s. I think Shakti was even better without John [McLaughlin] when Shankar, Vikku [Vinayakram] and Zakir [Hussain] continued and just did records as a trio. I think the records they did as a trio are absolutely unbelievable. I think the genius is Vikku and Shankar really. Zakir is great and fantastic, and John has his thing together. I don't want to be negative about John in any way. Shakti was definitely great and the combination of Western and Indian influences was all very good. But I think it is even better when the trio is doing this very developed form of South Indian Carnatic classical music. It's astonishing to me. So, that influence is very clear in what I'm doing and in John's playing. But there are other aspects too. I have been listening to a lot of other Indian, Pakistani and Oriental music. What comes out is a mix of Western and subcontintental music if you will. It's the same phenomenon as Shakti, but in another sense, it's not necessarily the influence of Shakti that creates what we're doing. It doesn't really matter. These are just names. It's how you categorize and identify certain aspects of music. I don't care if people think we are influenced by this or that or how they relate to it. The important thing is there is some kind of understanding of what that is and that they like it.

You share Selvaganesh with the new Remember Shakti line-up. What do you make of the reformed group?

It's something a little like "Let's reform Mahavishnu." Obviously, if you're going to have Srinivas, Zakir and Selvaganesh in a group, it's going to be great. How can it not be? I think Srinivas is absolutely wonderful and fantastic—one of the greatest. It was an absolute honor and pleasure when I got to play with him. But why is it called Remember Shakti? In order to capitalize on a brand name. I don't have any moral standpoint on this. I don't think it's necessarily bad for them to do that. But they could just call the spirits by their own names. There's no great musical reason for the name. It's purely financial and about career aspects. Had Vikku, Shankar, Zakir and John got together again, then yeah, that is Shakti as we know it and it would be more digestible.

Shawn Lane is an integral presence on many of your recent records. Describe your working relationship.

We met back in 1993. He was the first musician I've ever come across that had the same amount of diversified musical interests I had. He covers all the bases from classical and ethnic musics to jazz and understands everything I'm interested in. We have the same reference book, which makes it very easy to communicate musically. He has a very sharp mind. We don't actually need to rehearse. It's enough to explain or run things through even over the telephone and next time he'll remember it. And during concerts, one of us plays a theme and the other picks up on it later and develops it.

What made you seek out Buckethead for the Octave of the Holy Innocents sessions?

Buckethead is a very interesting guy. He's a very nice, smart young man and has his own kind of aesthetic that can seem limiting, but he definitely has a musical language and something to say. He's definitely different. He was working with Bill Laswell at the same time I was living in New York and we hung out. I liked him. He was always playing electric on everything he was doing. It was interesting to see what he could do with acoustic guitar. I like the record and what he did. It's sort of minimalist in a sense. It's definitely a clear musical statement and makes sense to me.

I'm told you have a very exacting presence as a bandleader. Is that reputation justified?

[laughs] I'm not sure that's the way I would see myself, but I guess I am sort of a conductor in the formal structure of the music, especially when it comes to us doing totally improvised music. Someone has to direct and transmit when things are supposed to start and finish. But you know, I'm open to what happens also. It's not like I'm really controlling. If somebody has made the observation, I'm sure it's valid in some sense. I don't have a vision in mind most of the time. I like certain people and I want to get together with those people and find out what we can do together. I offer space for everybody to exist. Except for the last album where we did compose a little bit, I haven't really composed anything for anybody in over 10 years. It's more of a collective effort of getting together and seeing where music wants to go by itself. My work with Shawn is definitely totally wide open. We influence, inspire and copy each other, but I'm not telling anybody what to play. If anybody tells anyone what to play, it's Selvaganesh who tells me how to play certain rhythms. In that sense, he's my teacher. I would be an idiot if I tried to teach Selvaganesh rhythmical stuff. That would be an utter waste of time. He has the knowledge.

Do you feel you're still learning and evolving on your instrument?

Oh, tremendously, yeah. I'm not at all where I want to be yet. We're entering the mystical realm here. I can't explain it. It's there in a very undeveloped form. I'm starting to find my voice. I still want to get to the core of what I'm playing and how that relates to the instrument I've chosen.