Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Allan Holdsworth

Unconscious Expression

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2008 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Carvin Guitars

Photo: Carvin Guitars

Unquestionably, Allan Holdsworth is one of the most unique, engaging and adventurous musicians to ever pick up an electric guitar. The accolades and acclaim that have come his way across his four-decade career are unparalleled. But he’ll have none of it. He’s on an eternal quest to hone his chops, and compositional and improvisational prowess. Holdsworth feels there’s always room to grow, and while he appreciates the praise, he compartmentalizes it to immunize himself against coasting on his laurels.

Holdsworth’s sound is an impossible-to-replicate combination of complex intervallic progressions, astonishingly fluid legato lines, and intricately-architected chord shapes. He’s put them to use across more than a dozen solo albums of singular jazz-fusion, as well as in superstar rock, jazz and pop contexts including The Tony Williams Lifetime, Soft Machine, U.K., Gong, Bruford, the Jean-Luc Ponty Group, and Level 42.

His latest release is Live at Yoshi’s, a DVD recorded as part of a Tony Williams tribute project with keyboardist Alan Pasqua. The group also features bassist Jimmy Haslip and drummer Chad Wackerman. It’s the first major Holdsworth-related output to emerge since the 2002 live CD All Night Wrong. A career overview compilation titled Against the Clock also came out in 2005. However, until recently, Holdsworth performances and new recordings have been few and far between this decade.

Over afternoon pints in an Oakland, California pub during a week-long stint at the legendary Yoshi’s jazz club, Holdsworth discussed the reasons for his long absence from the scene, his recent return to the stage, and his upcoming activities. In addition, he indulged Innerviews by reflecting on several of his previous key associations.

Photo: MoonJune Records

Photo: MoonJune Records

You’ve recently been more active in terms of touring and working on new material than you’ve been in years. Why did you pause your career and what’s behind the resurgence of activity?

Things were going well until 1999 when I went through a divorce and that changed everything. I lost my studio and had no way of working, so I was temporarily displaced for the first year or so. I was living with friends, floating around, and things ground to a halt. I went into a big downward slide and didn’t do anything. I wasn’t interested in playing. Meeting Leonardo Pavkovic, who runs the MoonJune label, was the biggest thing in getting my career going again. He’s been amazing in helping me manage a lot of things. I started touring again during the last two years and I’m going to have to tell Leonardo to stop, otherwise he’ll keep me on the road forever. [laughs] I also started working again on two album projects that were never finished. They should both come out in 2008. I also have a few tracks that I’ll be finishing for Chad Wackerman’s new solo album. That one has been going on for awhile too. I did quite a few tracks for it in Australia around the time of the All Night Wrong project. So, I’m now playing catch up. I put out the Against the Clock compilation just to do something. I figured there were enough albums out that we could put out a reasonably good “best of” from them. I thought it was also a good release for people who weren’t familiar with my work.

The first new CD is Snakes and Ladders, coming out on Steve Vai’s Favored Nations label. What can you tell me about it?

I signed a deal with Steve around the time I got divorced and he never got his album. He’s been unbelievably patient. The reason he hasn’t bugged me is because he’s a musician and understands that things can go wrong. Usually, a business-oriented record company guy would be beating down my door by this point.

Snakes and Ladders is an interesting record because it has two sets of people on it. Part of the album has Jimmy Johnson on bass and Gary Husband on drums. It also features another rhythm section I was touring with comprised of Ernest Tibbs on bass and Joel Taylor on drums. People have always asked me how different personnel change the music, and Snakes and Ladders really depicts that. There’s one tune that appears in two different versions on the album, played by each set of players. It sounds completely different because of the way they interpret it. With Jimmy and Gary, the music is a bit more high energy and rock-oriented, and with Ernest and Joe, it’s a little softer and goes into Sixteen Men of Tain territory. The record that comes after Snakes and Ladders will be another trio record, with Chad Wackerman and Jimmy Johnson, who I’m currently touring with.

Discuss the creative process behind Snakes and Ladders.

Because of the different way these groups play, I chose to do some tunes with one group and not the other. In general, I was writing tunes that were designed for each unit. My writing process starts the same way, regardless of who I’m writing for. I start by improvising and when I get an idea, I’ll keep working on it. Sometimes nothing happens. For instance, during my six-year hole, I wasn’t feeling very creative at all and lost interest in music. I didn’t go see music. I wanted nothing to do with it for a long time. Now, I’m writing again and have quite a few new tunes that we haven’t played yet because we haven’t had time to rehearse them. I’m looking forward to finishing this album and moving on to the next one.

How do you go about capturing ideas during your writing process?

Ten years ago, I used to record things when I improvised. I’d put on the recorder and start playing and if I found something interesting, I’d go back and listen and think “Oh yeah, I can work with that.” Sometimes, I’ve gone the way of not recording anything at all. It can sometimes be about how I feel at that point in time, and I just scribble the music down and keep going back to it until I can put it into shape. Sometimes things come really fast and some things take months. Take “Sphere of Innocence” from Wardenclyffe Tower. I wrote the whole tune in a couple of hours but there was a modulation in the middle of it that resolved in a way I wasn’t happy about. Ninety-nine percent of the piece was done in less than a day and it took months to finish the other one percent.

When you write music down, are you using standard notation?

No, I have my own system that I use and only I can figure out what it means. [laughs] It’s based in intervallic permutations. If I think of a chord, I see the scale it comes from and just write that down. If it’s a specific chord which the head of a tune is based on, I write down the actual dots to show me where my fingers go.

Do you read or write conventional music?

No.

That’s hard to believe.

I started out learning to read because my father was a great piano player who read very well. He always encouraged me to read and I did when I started playing clarinet in my youth. I found it relatively easy to read while playing the clarinet because most of the time there was only one place where a note would exist most of the time. With the guitar, it was totally confusing because you have a lot of choices in terms of where you can play a note. So, my dad caught me a few times when I just memorized note placements. He’d give me new things and I’d screw them up and he knew I wasn’t reading. Eventually, I didn’t bother with it anymore.

Allan Holdsworth, Chad Wackerman and Jimmy Johnson, live at STB139, Tokyo, 2008 | Photo: MoonJune Records

Allan Holdsworth, Chad Wackerman and Jimmy Johnson, live at STB139, Tokyo, 2008 | Photo: MoonJune Records

How do you communicate with the band when you present new music to them?

I just play it for them. I’ll either record it and give them a CD or just play it during rehearsal and make suggestions about how I would like it to go, and that’s basically it. I recently started recording things again, which seems to be a good way of doing things. I also like to write things on the SynthAxe because I can record directly into a sequencer and play it back. It still works pretty well.

So, the SynthAxe is still lurking out there somewhere?

Yeah, but I just use it in the studio. It stays there. It’s probably going to die soon at some point.

You’ve been saying that for more than 15 years. [laughs]

True. [laughs] It’s not roadworthy, but it is still working.

What tend to be the biggest challenges when you’re writing?

The biggest problem is that I’ll start out trying to do something and never consider what it will be like to solo on the harmony. People often come up to me and say “It must be great when you write your own stuff because you can make things easy for yourself.” Unfortunately, that’s not true. A lot of the time, I have more problems with my own music than I do playing other people’s music, and it’s unintentional. Sometimes, I’ll start out and say to myself “Oh, you can write this tune and make it simpler. Go ahead and make life easier for yourself.” But it never happens. It always morphs into something else and I’m back figuring how I’m going to play over all these chords, so I gave up on that idea. I just let the music play out the way I hear it and just figure out all the scales and how I’m going to solo over it later. I make a little roadmap for myself and that’s pretty much it.

Photo: MoonJune Records

What yardstick do you use to determine when a piece is ready to go?

When it feels complete. I have a lot of ideas where something is there, but I know it’s nowhere near completed. So, I keep working on it until it makes a complete circle. It’s like putting two ends together. I keep working on a tune harmonically until I feel there’s a resolution. I also like to modulate things, so even though it sounds like I’m playing the same thing twice, it’s being played in a different key. You hear that on the tune “Tullio” on Hard Hat Area. I think it’s the longest chord sequence I’ve done. The whole solo section for keyboards and guitar is the same. It sounds like it’s almost repeating, but if you listen, you realize the keyboard solo happens just one time. It’s an example of how I let something complete itself in that I keep playing until I feel the piece makes a whole circle.

When it comes to feedback on your music, whose opinions do you value most?

The guys that I work with, because they’re the closest people to the situation. I always ask them “Does this sound a little bit silly?” They’ll usually give me an honest opinion.

I caught you live several times in 2007 and the audience loved what you were doing, but at some point during every show, you stopped and apologized to the crowd for your playing. What do you make of the gulf between their perceptions and your own assessment of your performances?

I’m really flattered that people enjoy the music. Most of the time the audiences are great people and really encouraging, but that has no effect on me as to what I perceive happening myself. That’s the only thing I can go by. The difference between a good and bad night is that I probably wouldn’t apologize. That happens maybe once a year. It’s very rare. [laughs]

Several musicians you’ve worked with who love your playing have said they can’t understand why you’re so hard on yourself since you blow them away all the time. Do you use that as a tool to push your creative limits?

Yes, I’ve done that a few times. Things can be hard because sometimes when I play something, it’s going to have similarities to something I’ve done before. I try not to do the same things so it feels like I’m really improvising, but sometimes I catch myself and think “Geez, didn’t I hear that somewhere else?” and I’ll go and erase two or three tracks at a time. I did a lot of stuff for the guys in Planet X. I was supposed to play on everything on one of their albums, but in the end I only played on two tracks. I originally played on seven tracks, but I came back from the pub one night and played the stuff and hated it, so I erased it. The next morning, I thought I should listen to the original tracks again to see what I could do with them, but in my stupor, I had actually reformatted the drives and needed to get the material retransferred so I could start again. Unfortunately, I ended up not finishing the project. It’s funny. Jimmy Johnson would sometimes come to my house and pay a visit just to make sure I wasn’t erasing everything when we were working together. [laughs] I dunno. I always want things to be better and it never is in the end. You eventually just give up and go “Okay, I guess that’s it.” Once a record is done, I never worry about it again. I’ll slave over it for months and once I get to a certain point, I move on.

You’re obviously very aware that many consider you the greatest electric guitarist in history. How do you internalize that feedback?

It makes me cringe. It’s nice to think that you could do something that other people enjoy. I think my own love of music is why I keep doing things. As for other people making those comments, I have to ignore them because I don’t believe them myself. I can only do what I do and I keep trying to make progress. Sometimes it seems like I can learn and make a leap forward and then things just stop for awhile. I get frustrated because music is never-ending. You can never know anything. That’s the one thing I got comfortable with immediately as a musician—the fact that I could never know anything about music. I think anyone who tells you they know a lot about something really doesn’t know very much about it at all.

How do you feel you’ve evolved as a guitarist over your career?

I keep learning, studying, and experimenting. I keep getting new information because I always think improvisation must be an unconscious release of things you already know somehow. Usually, anything I’m working on is something I can’t force to happen. If I try to make something happen, it doesn’t sound right. It takes maybe a couple of years before something I’m working on now will find its way out naturally. So, I have to let myself struggle with things and try not to force them into action.

The last time we did an interview, you were heavily into baritone guitars. What’s your guitar of choice these days?

I quit playing the Steinberger-based baritone guitars because I had to carry around too much stuff. In recent years, it became impractical to carry two or three guitars when flying. Unfortunately, that means we don’t really play much Wardenclyffe Tower music, which heavily featured the baritone guitars. I can transpose the tunes but they don’t sound the same. So, I put those tunes on the back burner and hardly use the guitars anymore. I might pull them out for a recording project if someone wants me to play on a song and I think one might fit that track. These days, I typically use a Bill DeLap wood-bodied, headless guitar. I’m totally hooked on headless guitars. It’s hard for me to go back to a headstock and big body guitar. They don’t feel comfortable at all anymore. The DeLap is totally custom, but still all-Steinberger based. It has the Steinberger TransTrem and headpiece.

You’ve recently been touring with Alan Pasqua as part of a Tony Williams tribute project. What inspired you guys to make this happen?

Alan was on the road in Europe and a promoter suggested the idea. He said “Why don’t you get back together with Allan?” That planted a seed and we spoke to each other to see if it could work. I used to call Alan once in awhile, usually because I was listening to one of his albums. I really love his playing. So, we thought “Let’s do a little tribute to Tony.” We had a rehearsal and it was going well. We tried it as an experiment and we’ll see what happens. We’re talking about doing a studio record with new material as a tribute to Tony. It’s been 30 years since I last played with Tony. It makes you realize how old you are.

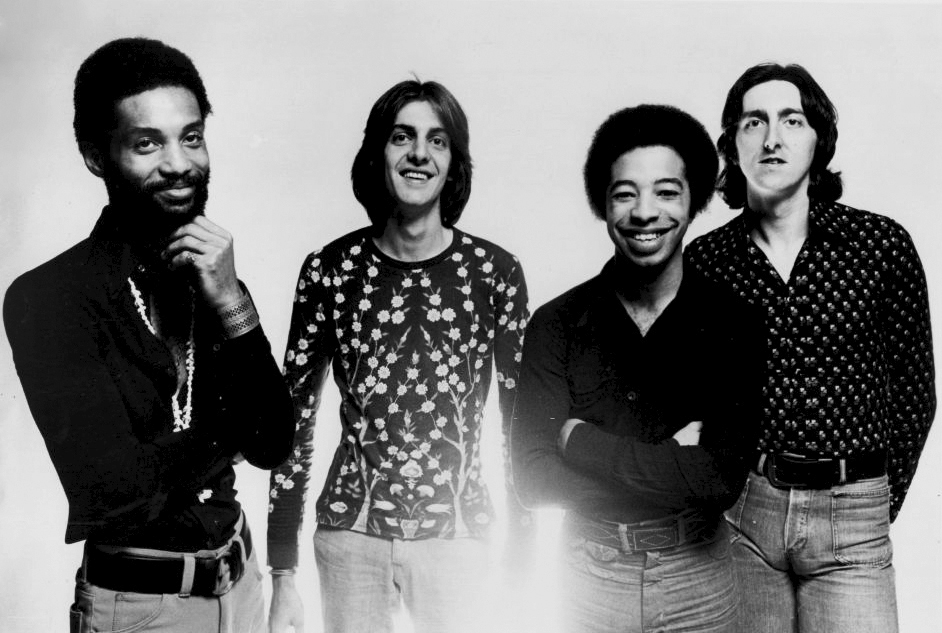

The Tony Williams Lifetime, 1975: Tony Newton, Alan Pasqua, Tony Williams, and Allan Holdsworth | Photo: Columbia Records

The Tony Williams Lifetime, 1975: Tony Newton, Alan Pasqua, Tony Williams, and Allan Holdsworth | Photo: Columbia Records

Reflect on your days playing with Williams.

It was as amazing as it was unbelievable. I learned so much from Tony. He is the reason I never give musicians who play with me any direction on how to approach anything. Tony never did that with me. He would let me dig myself a hole. I’d stand there and say “What am I supposed to do?” He made me find my own way. When Gary Husband first played with me, I realized he had been listening to some of my albums and was trying to do something like what he heard on them. I told him right away “No. That was something that happened as an improvisation and it was only meant to happen that one time. Forget the record and do your own thing.”

Nobody played like Tony. When he switched from the jazz thing to whatever you would call what Lifetime did—fusion, I guess—no-one had ever heard anybody play the drums like that. I still have never heard anyone who does. It was his own thing. I was only in his band for a couple of years. It was a short stint because of management and financial problems. I was staying at his house for awhile. He had a tall townhouse in New York City at 141st Street and Broadway. There were a couple of top floors he didn’t use and he’d let me stay there and we would play all the time. He kept inviting people over. For awhile, Lifetime was just me and Tony. There were no other members, so different bass players would come by until we found someone he really dug. Jeff Berlin came by and so did Jaco Pastorius around December 1975. It was an interesting time.

What was it like to work with Pastorius and Williams as a rhythm section?

It was just really amazing. I loved Jaco. There are some recordings of the rehearsals, but I don’t know where they are now. They would be embarrassing to hear. Tony was looking for someone who played less than Jaco. He wanted something specific in the bass division. Jaco was a really sweet guy and a ridiculous bass player. It was really great to play with those guys.

MoonJune recently released Floating World Live, a Soft Machine concert CD from 1975. What are your thoughts about the disc?

I never listened to it. I just can’t. I heard about five bars of it, turned it off, and said “Go ahead, put it out.” [laughs]

You allowed an album to be released without hearing it? That seems really unlike you.

It makes me cringe, but we played the gig, it was recorded, somebody has the recording, so why not put it out? I can’t stand listening to myself. I never listen to live recordings. If I did, I would just quit. I haven’t even seen the new Live at Yoshi’s DVD. I can’t watch it. I heard a few bars and said “Oh no. Stop.” I can’t do anything about these things. Personally, I would choose not to do any live stuff because everyone does it for you. I must have at least 200 bootleg CDs that were sent to me personally from the live gigs that someone else recorded. So, why would anyone need any more? There are hundreds of recordings out there.

Bootlegging used to be one of the biggest thorns in your side. What’s your take on it now?

I stopped caring. At one time, live recordings were too sacred or something to me. I felt like someone putting out a bootleg in any form was akin to Native Americans having their photographs taken in that something sacred got stolen. I quit caring because as the Internet and pocket and cell phone recorders emerged, it hit a point where you can’t stop it from happening, so why bother? I gave up. It’s okay. Everyone can record whatever they want.

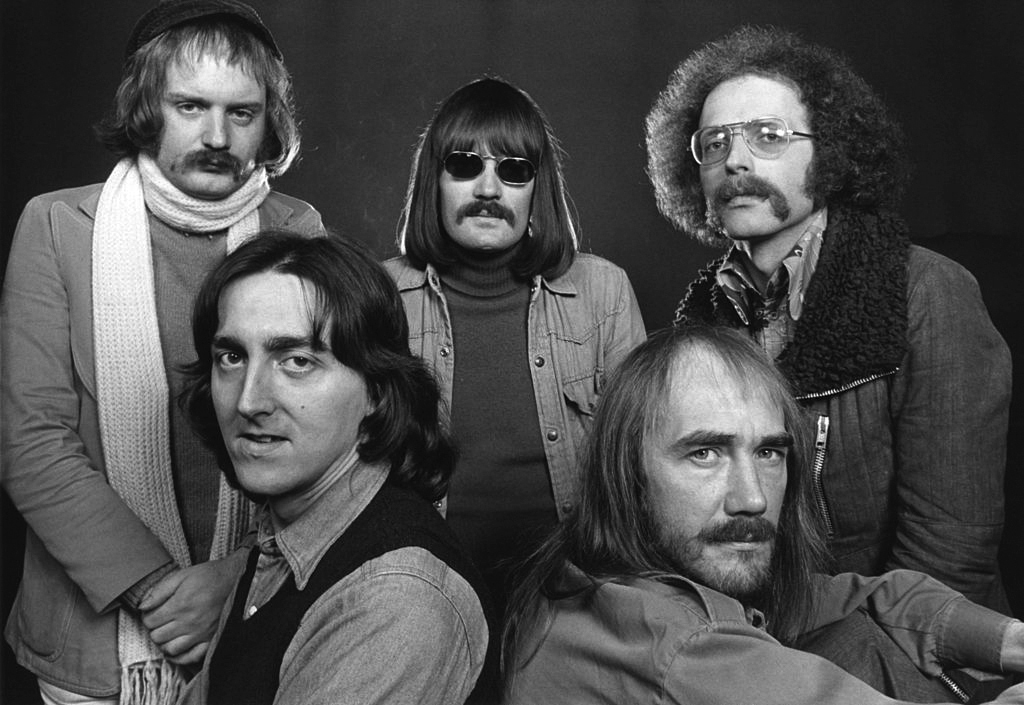

Soft Machine, 1975: Karl Jenkins, Allan Holdsworth, Mike Ratledge, Roy Babbington, and John Marshall | Photo: Harvest Records

Soft Machine, 1975: Karl Jenkins, Allan Holdsworth, Mike Ratledge, Roy Babbington, and John Marshall | Photo: Harvest Records

Going back to Soft Machine, how do you look back at your experience with the band?

I really enjoyed playing with that group a lot. Before that, I was playing with Tempest, Jon Hiseman’s group. That was more rock and roll. I met John Marshall and Karl Jenkins through the Musicians’ Union. There was a guy at the union who was organizing some clinics for Soft Machine, but he wanted a guitarist in there as well. He asked Soft Machine if they would consider doing these clinics with an extra guy and they said “Sure.” So I rehearsed with the band and we did four or five clinics. After, they asked if I would join the band and I said “Yeah.” There was a lot of freedom in the group. Most of their pieces were quite simple harmonically, but they were in odd time signatures which was something going on at the time. I can’t count anyway, so everything is in one to me, but I really dug it. I love Karl, John, Roy Babbington, and Mike Ratledge. It was a lot of fun.

I revisited Soft Machine with the Soft Works project. I felt it was something I should do, but it became a logistics problem with the three guys being in England and me being in America. Another reason for why we didn’t do more is because sadly, Elton Dean passed away. That was really tragic. Before he went on a vacation to Tahiti in 2004, he stopped at my house and spent a couple of days with me. On his last day with me, we went to the golf club to get a few beers, then he left and it was the last time I saw him.

You recently collaborated with with Jean-Luc Ponty on his Acatama Experience CD. What was it like to work with him again?

It was great. I’ve always been a big fan and love his playing. He’s a sweet guy and he plays like he is. He called one day and asked if I’d be interested in playing on a track on his new album and I said “Sure.” He’s in Paris, so he sent a file over and I played the solo and sent it back in the mail. It’s funny to say “The solo’s in the mail” but that’s how we did it. [laughs] It’s a nice track and I’d like to do more with him. The whole record was pretty much done, so he just wanted a guitar solo for the one tune.

When you played in Ponty’s band, it was one of the rare occasions you shared the stage with another guitarist—in this case, Daryl Stuermer. What was it like to share the lead guitar role?

It was alright. We’re radically different, so it never turned into a war. A lot of times when you get two guitarists together it’s like dueling banjos.

Stuermer told me he would watch you in awe and that it was a tremendous learning experience for him.

I was doing the same thing with him. I really thought Daryl was great. I had seen him play as part of Jean-Luc’s band prior to my joining. It was a lot of fun to work with him. The fact that we’re so dissimilar made it work together quite well.

You’re now in control of the entirety of your back catalog. What are your plans for it?

We reissued Wardenclyffe Tower with three extra tracks that were only on the Japanese version. I was thinking about rereleasing the rest of them, but then I spoke to my music lawyer. He said he thought the CD thing was evaporating and that reissuing those albums again may not be a very practical thing to do. They’re all available on iTunes. It would be a very expensive proposition to reissue 10 records because I would have to remaster them which can cost a few thousand dollars a disc. The only way I could do it is one at a time. I still haven’t decided what to do. I could make another compilation and leave it at that.

Having said all of this, I would like to remix the I.O.U. album because the last time I played it off the original two-inch tapes, it sounded so much better than the album. The record was mixed in two evenings. I think everything, but especially the drum sound, can benefit from a remix. Also, the tapes were stolen during that session and two of the tracks were gone by the time we mixed the album. Later, the studio owner found the guy who stole the tape and got it back. So, there are two tracks that aren’t on the original I.O.U. album that I would include. I’ll have to bake the tapes in order to do it, but I think it would be worth it. The recorded sound was just so much better than the CD and I think I can do it a lot more justice.

You turn 62 this year. Some musicians I’ve spoken to in their early sixties have felt a need to accelerate their output and take creative chances they’ve previously avoided. Does that hold true for you?

No. Sometimes I slap myself in the morning say “Wow, I got up again!” [laughs] So, I don’t think about that stuff. Maybe it’s because I’m trying to get back on track after separating from my wife. I was really uprooted. It really punched a big hole in everything and I’m crawling out of it. I’m still playing catch up. If I was caught up, I might be more inclined to focus on what you describe. In general though, I’m interested in doing something gnarly. I want to make music with a few less left turns and focus more on the energy side of the equation, rather than just the harmony stuff. I want the music to be more aggressive than the last studio album. Let’s see what happens.