Joan Jeanrenaud

The Beat of the Moment

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2011 Anil Prasad. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution, No Derivatives license.

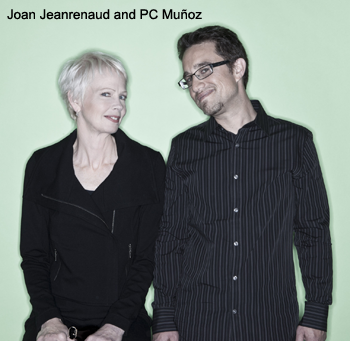

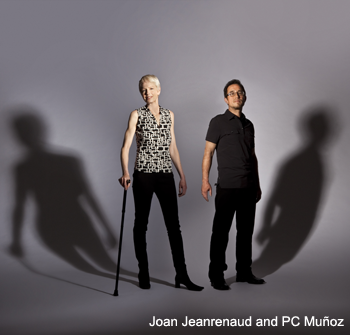

Playing it safe is a concept cellist Joan Jeanrenaud has total disinterest in. Her deep, varied career reflects a restless creative spirit that most recently manifested itself on Pop-Pop, a new duo album with producer and percussionist PC Muñoz. The disc seamlessly blends cello, classical, electronica, and hip-hop influences. But perhaps the most important element is fun, something Jeanrenaud and Muñoz clearly had a lot of when making the disc. Unlike Jeanrenaud’s carefully-architected previous albums, Pop-Pop found her and Muñoz literally making up the album as they went along in the studio. It’s a record driven by visceral creative impulses and a desire to capture the duo’s collective muse at its most riveting.

“Joan possesses the kind of qualities that would thrill any collaborator: incredible technical facility, boundless musical imagination, an adventurous spirit, and a genuine love for the give-and-take of true collaboration,” says Muñoz. “For me specifically, it's a nice bonus that she's also funky. She's from a town right outside of Memphis. She grew up listening to rock and roll and peeking in at the blues and soul music pouring out of the Memphis clubs. In a very real way, her musical ancestry is as much Sun and Stax Records as it is Bach and Cage. That combination makes for a very unique compositional voice. It's always exciting to hear what she's going to come up with next.”

Jeanrenaud shares Muñoz’s enthusiasm for the partnership. Pop-Pop is a natural evolution from 2008’s Strange Toys, her second solo album after leaving Kronos Quartet in 1999. Strange Toys, also produced by Muñoz, was comprised entirely of Jeanrenaud’s own compositions. It was a significant progression for her after a career previously spent performing expansive works by some of the world’s most renowned composers via Kronos Quartet. The ambitious and diverse album found Jeanrenaud exploring a wide variety of neo-classical, avant, and occasionally beat-oriented contexts.

As part of Kronos Quartet, Jeanrenaud scaled tremendous heights. During her tenure with the group from 1978 to 1999, the group recorded 30 albums that sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and performed more than 2,000 concerts across the globe. She also worked with some of the new music world’s most influential composers, including John Cage, Morton Feldman, Philip Glass, Henryk Górecki, Witold Lutoslawski, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, Frank Zappa, and John Zorn—just to name a few. Her reasons for leaving the highly-influential act were a combination of a desire to seriously pursue the realms of improvisation and composition, as well as a Multiple Sclerosis diagnosis that made her reevaluate her life trajectory. Jeanrenaud is confident she made the right choice at the right time. Her ever-evolving, multifaceted solo career, which now also involves composing for other artists, is a testament to following one’s instincts.

What attracted you to the beat-driven universe of Pop-Pop?

PC Muñoz had a lot to do with that. He produced Strange Toys. I didn’t know anything about him or his work before then, but once I met him and worked with him, I was really impressed with his ears. When you work with a producer for the first time, you’re not sure if he’s going to hear the same things you hear. But it was amazing. After a couple of days, I realized PC hears exactly how I hear, which is great. So I became very interested in his music and what he does. He’s very beat oriented. That’s part of so much of what he does. I’ve always been interested in beats and rhythm too. That became my role in Kronos in a way. As the cellist, I was also serving as the bassist and drummer, which are the foundation of every group.

We did a few things with beats on Strange Toys and that made me feel like it was a direction we could go further in. On Strange Toys, I started working with loopers so I could create a lot of different parts, all generated by me. At the time I thought “Am I just recreating a string quartet here?” But it kind of made sense too after all of those years being in Kronos. Certainly, Kronos opened up my ears to so many different possibilities. Michael Daugherty even wrote a piece for Kronos that had beatboxer stuff on it. Kronos also worked with Tony Williams at one point, who wrote a piece for us called “Rituals for String Quartet, Piano, Drums, and Cymbals.” I’ve always enjoyed working with drummers and people who keep the beat, but I’ve always liked the role of holding down the beat too. So given all of that, it isn’t out of the ordinary that I ended up doing stuff like what’s on Pop-Pop. So PC and I talked about doing an album involving a DJ and pursuing different mixes. Finally, I said to PC “I love what you do and I think if we do an album together, it will satisfy all of the things we’ve been talking about in terms of bringing in different sounds.” So that’s how it happened.

The idea was for the album to be all pretty short tunes. We call it “the pop record that’s not pop.” [laughs] That was always in our thinking. We’d think “Wouldn’t it be great to make a pop record? How would we do that with the cello and beats, using our skills?” We thought it would be great if it got played in dance clubs. Whether that happens or not, we’ll see. [laughs]

Are there any electronic musicians of note that inspired you to explore this direction?

I’ve always listened to people like Tangerine Dream, and Michael Hoenig is a good friend of mine. Pat Gleason, who I was married to, is also an excellent synthesist. He did Vivaldi’s “The Fours Seasons” on a Synclavier. Wendy Carlos is someone else I like. I remember hearing Switched on Bach and that was a big thing. I got to meet Wendy and became very interested in what she does. There have always been people in my past that have enabled me to be aware of what’s going on in that field.

How did the collaborative process with Muñoz work?

We just went into the studio and constructed the music, which is very unusual for me. That part took awhile to get comfortable with. Usually, you pay for your studio time, so when you go in, you know exactly what you’re going to do and you record it. But this album was a great opportunity in which PC and I went to the studio and worked out the music together, more like pop people do. At first that was hard, because I felt Justin Lieberman, the engineer, and PC were just sitting there observing. It’s such a private thing when I work on music at home, so to be doing it in front of those guys in the studio was awkward at first. Then I got used to it and realized it was a very good collaborative environment because everyone could immediately talk about things as they happened and try out different ideas.

Sometimes PC would give me a beat pattern and I might say “PC, that’s too regular, give me that in 5/4 instead of 4/4.” And then he would generate something else, send it to me and I would work with that beat structure. Just like I often do at home, I would fool around with this material, create layers, and see what works together. But then there were certain times like on “33 1/3” in which I actually generated the material and PC added the beat stuff on it afterwards. So we would go back and forth a lot in different ways. There were also certain times when I made a mistake, but ended up liking the mistake. Sometimes, instead of looping something eight times, it would get looped seven times, and I would think the result was interesting. A lot of stuff like that happened.

Did Muñoz have a background in new music prior to working with you?

Not really, but he’s worked with a lot of singer-songwriters, which was valuable for me. He’s very familiar with the structure of pop tunes—the verse-chorus thing. So these tunes were sort of based on that structure, even though we didn’t adhere to that at all. A lot of the time, it was something we would talk about. We would have things come back as a refrain. PC influenced me in that way. PC doesn’t read music, so even when we did Strange Toys and did edits, he would take notes on his phone which were so clear. That was amazing to me as I have to write this stuff out in a score. But he’s able to do it all in his head. A lot of improvisers work that way, but I rely on the classical tradition of having something written down. I wish I could do it the other way more.

Strange Toys was your first foray into creating an entire album of original material. What spurred you into pursuing the universe of composition so deeply?

It came about because the Talking House label said they wanted me to record a CD. I had a lot of material I had worked on since I left Kronos. Also, after I left Kronos, I started improvising, because I knew that was something I wanted to do more of. I said “Great, now I have the time. That’s what I’ll do.” As a composer friend of mine said, “Once you start improvising, you’ll start writing music.” And that’s exactly what happened. So the first 10 years of my writing and that accumulation of material is what ended up on that recording. The label left the pieces that went on the album up to me, so I chose to focus on documenting my own writing. I took the stuff I liked best and put it together.

Tell me about your background in composition.

When I attended Indiana University, I was fortunate to learn a lot from really fine teachers, composers and players. I took one semester of composition. I knew Fred Fox well and played in his contemporary music ensemble. I also took improvisation classes, as well as lessons from Dave Baker and Joe Henderson. But I never had the time to concentrate on that side of things. All of the years with Kronos paid off tremendously though. I performed such a wealth of music and worked with so many composers. I got a lot from those experiences which helped me when I started working on my own music.

The Del Sol Quartet just commissioned me to write a four-movement piece for them. Last year is when I started writing music for people other than myself. It was a good step for me to get away from the looper to write for that context. The looper is useful, but it’s also limiting because you’re kind of locked into a tonality, but there are a lot of things you can do with that too. But I was getting to the point where I thought it would be nice to do something in which I’m not looping. In general, I’d like to get to the point where I’m writing more and more music for other people, and it’s starting to happen. The Estamos Ensemble also had me write a piece for them. In addition, Cornelius Dufallo, a violinist in New York, had me write a solo violin piece for him.

“Altar Piece” from your first solo album Metamorphosis was the first composition you released to the world. The piece was situated among works by Philip Glass, Steve Mackey and Hamza El Din. Was that a significant milestone for you?

It was. It was very much more a rock and roll piece. I did it on my electric cello, which really influenced it. It was a nice moment for me. That album reflected stuff I was pursuing after leaving Kronos. I’ve always been involved in performance art and multimedia stuff. For instance, I did a piece called “Aria” that premiered at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts in San Francisco. And when I first left the group, I got into the Fluxus scene with Charlotte Moorman. I did a piece called “Ice Cello” in which I played a cello made entirely of ice. Stephen Vitiello manipulated the tones it made as it melted. The whole idea of questioning where the boundary between the audience and performer is interests me. Is it possible to integrate all of that instead of just sitting on stage and having the performer here and the audience there? That’s what I was thinking about during several of those projects, which were very interactive.

What are your composition tools of choice?

I use Pro Tools and Sibelius. I input my music into Sibelius. I used to always use pen and paper, but when I started working on the string quartet for The Del Sol Quartet, I did it right into Sibelius. “Dive” from Pop-Pop is one of the movements for Del Sol. It’s a four-movement piece. The quartet version is slightly different. Also, there are no other sounds other than the quartet in their version. The great thing about Sibelius is you can hear what you’ve done when you’ve put it in there. It lets me hear it back so I can go “I didn’t mean to do that.” You can catch things easier than my previous approach, which was sitting there and handwriting my stuff with my cello at my side. Pro Tools is also great because there are certain pieces I’ve recorded directly into it, particularly when I was interested in integrating other sounds. For instance, I’ve used the sound of crickets, industrial noises and even volcanic activity. So I would put that stuff into Pro Tools and play cello on top of it. I also have an Echoplex digital looper and Lexicon MPX G2 guitar processor. I realize those are really old tools, but I’ve had them a long time and they still work very well, so sometimes I go back to that stuff.

Last December, you recorded Vladimir Martynov’s “Schubert-Quintet (Unfinished)” with Kronos Quartet for their forthcoming album. Describe your thoughts about reengaging with Kronos after such a long absence.

Vladimir Martynov wrote the piece for Kronos plus extra cello. I think they were always interested in recording it, because it would be fun given I haven’t worked them in 14 years. We recorded it with Judy Sherman, the producer I knew so well when I was with Kronos, at Skywalker Sound. We recorded a lot of stuff there in the past. It was wonderful to play with them again. I still love those guys.

In general, how do you look back at your time with Kronos?

It’s much easier for me now to reflect on what Kronos has done and what its influence is on music. When I was in the group, it wasn’t something I considered or thought about too much. We always talked about what we were doing a lot, but not about how people perceived it necessarily. It was always “This is something cool we want to do. How can we figure out how to realize it and make it happen?” For instance, when Steve Reich wrote “Different Trains,” we started using amplification so we could compete with the sound of the pre-recorded tracks. Music was what always directed Kronos.

People used to always focus on the clothes and everything else. But those guys never wore suits or ties. It seemed crazy for them to do it on stage. They would be totally uncomfortable having that stuff on. So everything came about in an organic way. We thought “We’re playing new music. We’re not playing what everyone else is playing, so why do we have to wear what everyone else is wearing?” A lot of directions came from that way of thinking. It’s not like we ever thought “What kind of effect will this have on an audience?” Our focus was on managing and conceiving projects.

During your tenure in the group, you were all as close to rock stars as people could be in the classical music world. What was it like to have such a high profile and sell hundreds of thousands of records in the process?

It was fantastic, but at the same time, the whole thing happened so gradually. We started out at Mills College in Oakland, California and no-one had ever really heard of us. We traveled around California in Hank Dutt’s Toyota. [laughs] It was really small but we managed to fit everything in it. We always felt encouraged to do more of what we were doing, but I don’t think anyone in the group thought about ourselves that way. I think they still don’t. Now that I’m out of the group, I’m able to realize that Kronos truly played a big part in the direction of music to some extent. But when you’re in the group, you don’t think about that. You just feel lucky that you can keep doing what you love and make a living at it. We went to so many different places and worked with so many incredible composers. We played at Carnegie Hall, the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. Those were all high points for me. When I was in Kronos, I tended to look at what was happening at the moment, as opposed to how things were perceived by the outside world.

You remained on Kronos’ Board of Directors for 10 years after leaving the group. What role did that play in your transition to a solo career?

I did sit on the board and finally, after 10 years I thought “You know, I don’t need to be on the board anymore.” I didn’t feel like I was contributing as a real board member should. So that was one of the reasons I thought it was best to step off. But it was important for me to be there for those 10 years. It helped me transition from being in the group and seeing it every day. Essentially, it was my life. Being on the board was a whole other way of interacting with them. They handled my departure very well, and a lot of that had to do with Janet Cowperthwaite, their manager. Originally, I was just taking a sabbatical the first year, and then it was clear that permanently departing is what I should definitely do. The whole thing was a very gradual process and handled in a nice way that let me always keep my connection to the group. There was definite detachment, but it was good to see what they were up to. I’m very good friends with Hank. We went to Indiana University together and he’s how I got into the group. He joined Kronos a year before me. And when they needed a cellist, he called me.

It’s interesting. I never feel like I wish I was up onstage with Kronos right now. That surprised me, because you would think I would have those pangs. Obviously, I did the right thing for me and they did the right thing, because they’ve been able to continue doing exactly what they want to do on their schedule. They don’t have to make any modifications and they’re on their path. They’re doing great stuff, but I wouldn’t fit into that anymore. I don’t have any regrets.

Henryk Górecki recently passed away. What did he mean to you?

Oh wow. He was a big deal for Kronos. David Harrington wrote a really nice tribute to him. David mentioned the first time we recorded with Górecki, we were in Germany and there was a piano in the room. He didn’t speak English that well, so when he demonstrated something, he would do it on the piano, because it was a clear way of communicating. From that first rehearsal, he became very significant to Kronos. I didn’t get to play his “String Quartet No. 3” which I feel sorry about. He was going to write it while I was in the group, but he would take forever to complete pieces. You could never tell when he would finish something. It wasn’t until seven years after I left that he finished it. He was definitely central to Kronos. There have been a lot of other important composers like Terry Riley and Witold Lutoslawsky involved with Kronos too. David asked Lutoslawsky to write us something, but he said “Oh no, I’ve already written my quartet.” [laughs] It’s a superb quartet though.

Tell me about your affinity for jazz.

I was always interested in jazz since I was at Indiana University because a lot of people I hung out with there were in the jazz department. There were a lot of excellent players, including trumpeters and saxophonists, but there really weren’t any string players, even though Dave Baker played the cello. There were more string players in the classical part of the school. The jazz side was an important thing to be around for me. I took advantage of it and took courses from Dave. Prior to Indiana University, I hadn’t really listened to jazz. It was only during college that I became familiar with people like John Coltrane and Miles Davis.

You worked with Ron Carter on Kronos’ 1985 album Monk Suite. What was that experience like?

He was great to work with, even though I felt like I had to be careful because I was stepping on Ron’s toes. I was in his territory. [laughs] I learned a lot from the guy. He’s an incredible bass player and I love the instrument. Of course, the cello is as close as you’re going to get to the bass without playing it. I’ve tried playing electric bass somewhat, and it’s very fun. When I was in Kronos, I was always trying to do pizzicato things. I was very inspired by bass players and how they did stuff.

I’ve seen you mention Jaco Pastorius several times over the years. What do you find compelling about his work?

I just love the guy. He had the best sound. I thought he was truly imaginative with the choices he made on the instrument. I never heard him live, which is too bad. I did see Mingus play when I was at Indiana University, which was fantastic. I sat close by him in this little club. That was back in 1974. I also got to see Miles Davis too.

How did Kronos hook up with Tony Williams?

I got to know Tony through Michele Clement, a photographer who took a lot of pictures of Kronos. We’re really good friends. Her son Joseph Maslov did the cartoon record cover for Pop-Pop. He’s my godson. Michele also did the CD photos. Michele used to date Tony. When Kronos was playing Tony’s music, we would hang out together and I got to know him well. I’d go and see him play and he was an amazing, incredible drummer. He was also a really sweet guy.

Larry Ochs, Fred Frith and John Zorn are other key presences in your post-Kronos career. Describe their importance and influence on you.

Larry Ochs is guy who’s done a lot for me. When I left Kronos, Larry, Hamza El Din and Terry Riley were great at encouraging me to do my thing and improvise and compose. He invited me to do a lot of projects. He was the first guy who said “Why don’t you come and perform at our ‘New Music on the Mountain’ series?” I said “I don’t know Larry, what should I play?” He replied “Play anything you want. If you were ever going to try live improvisation in front of an audience, this is the one to do it for. They’ll be completely supportive.” So I did that. It was the first time I did anything of mine in public and it was great. Larry has taught me so much by allowing me to be part of several improvising groups. Now, I feel so much more comfortable in that environment.

I got to know Fred when I left Kronos, because he started to teach at Mills College, and I did too. I have a long relationship with Mills. I have three students there. So Fred was there and every once in a while he would perform a concert of his music and I would get invited to be the cellist for pieces needing a cello. I really liked what Fred was doing, so I asked him to write a piece for me and Willie Winant, another terrific drummer. Fred did a piece for us called “Save As” which is on his album Back to Life. You get a deeper experience with a composer when you get to work with them on their music.

I’ve known John Zorn for a long time because he wrote all of those pieces for Kronos. I even played in Cobra last August at Yoshi’s in San Francisco, which was a lot of fun. It was great to be part of the piece I played. When you play a piece, you find out so much more about it than when you’re listening. I also realized that I listen way differently now than I used to. I used to listen as a performer and criticize someone’s physical playing—their chops. Now, I don’t listen to that at all. I listen to the composition and think “Oh, I can rip that off. That’s a good idea. How can I use it? [laughs] It’s interesting to see how that’s changed.

You chose to release Pop-Pop on your own label Deconet Music. Tell me about the rewards and challenges of that decision.

I was surprised at how easy it was to start a record label. I went down to city hall and registered the business, just like you would any business. You can go online and learn everything you need to know. There’s a lot of paperwork which is interesting to a certain extent, but at another point, it’s “Oh God, do I really want to be doing this? Don’t I just want to be making music?” It’s a good thing to learn about. I’ve learned a lot. Who knows if I’ll release another record this way. I probably will because the label is there. It’s nice to not have to feel like I have to shop around and get people to take on my record. It’s also pretty cost effective. These days, record labels won’t give you anything to make a record. By doing it on your own, you take a chance. You probably won’t make any money either, but you’ll likely break even. So why not? I realized I was never going to recoup my costs by having someone else release it, but I might if I did it myself. There is something to be said for having complete control.

How did your Multiple Sclerosis diagnosis affect your creative mindset?

It took the wind out of my sails and really changed my focus, that’s for sure. I asked myself “Okay, what’s really important here? It’s my life, family and the people around me.” I also found myself thinking “What makes you happy? What keeps you interested in life and going forward?” All of that stuff became much more important. My career was never that important to me. I feel very lucky to have been thrown into the situations I’ve been thrown into. And even MS has changed my focus and direction in ways that are good. I like being home a lot more. I don’t miss being on the road. That’s a hard life and I probably would have kept doing that without thinking twice about it. I’m happy that I decided “Okay, I’m going to see where my artistic life can lead me.” It became a very creative thing for me. I still feel I have a lot to learn. I’ve played my cello for 44 years and I know how to do that, but I still find the instrument very intriguing.

Is there a spiritual component to what you do?

Certainly, emotions and feelings have always been paramount to music making for me. The whole purpose is to express yourself, and it’s an excellent outlet to do that without words. I’m not the greatest technician on earth. I’m going to be working on that until the day I die, but I strive to have the best technique I possibly can. If people hear me play and it makes them feel something, it’s because my work comes from a very emotional place. In some way, that’s a sort of spirituality. I’ve never been a deeply religious person by any means. If anything, I tend to gravitate towards the Eastern way of looking at spirituality, more than the Western. I ended up with a Tibetan doctor, because there are a lot of Buddhist principles that make a lot of sense to me. I think I’m much more logical in some ways than I am spiritual. So I think there is definitely spirituality in my life and how I look at things, but it’s not in the accepted way some might think of it. For me, it reflects more of an internal perspective on things.