Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

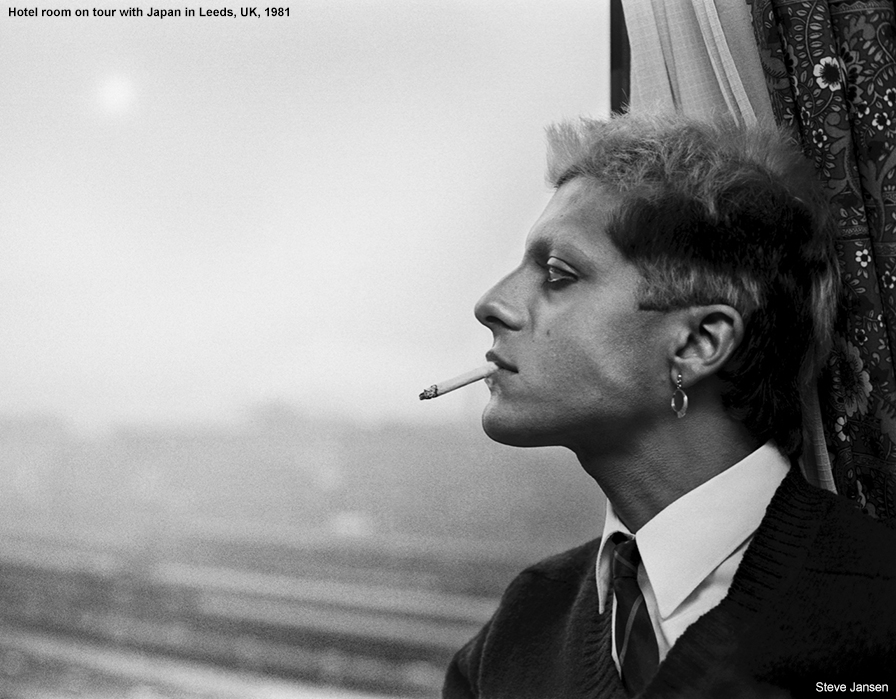

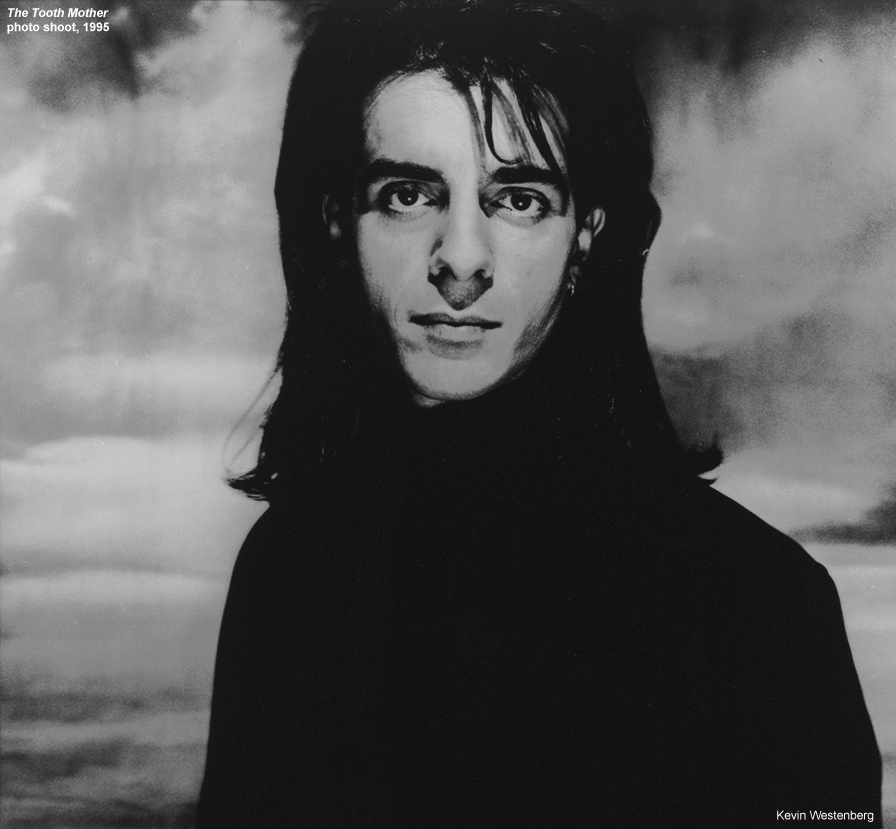

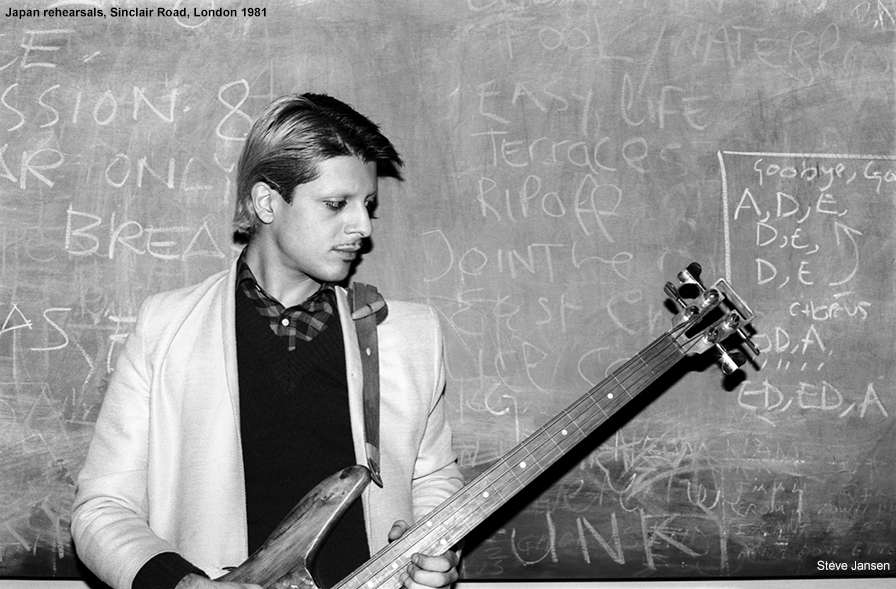

Mick Karn

Sculpting Sound

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1996 Anil Prasad.

It's like if Bootsy was Moroccan." That's how guitarist David Torn once described Mick Karn’s fretless bass work. It’s just one of the many ways musicians and listeners alike have attempted to explain Karn’s exotic sound to the uninitiated. But the fact is, a whole lot of people have heard his one-of-a-kind approach whether they realize it or not.

Karn is best known for his role in the British art-pop group Japan. He and his bandmates David Sylvian, Richard Barbieri and Steve Jansen were responsible for some of the most interesting and eclectic pop of the early '80s. Best-selling albums like Tin Drum and Gentlemen Take Polaroids seamlessly combined Western pop traditions with Eastern influences into an accessible whole. Those records, along with Japan’s penchant for wearing makeup and elaborate outfits, helped defined what became known as the "new romantic movement."

After the group’s acrimonious break-up in 1982, Karn began a solo career that enabled him to significantly evolve as a bassist and composer. The decade saw him release two albums: 1982’s Titles and 1987's Dreams of Reason Produce Monsters. They explored expansive territory ranging from mercurial bass-driven workouts to meditative soundscapes to melodic pop epics. He also found plenty of session work with the likes of Kate Bush, Midge Ure, Joan Armatrading, and Gary Numan.

The ‘90s began with a short-lived reunion of Japan’s members who recorded as Rain Tree Crow. The group released an adventurous and moody self-titled effort in 1991. In contrast to Japan, the disc favored complex, emotionally-charged atmospheres that showcased how far its members had evolved from conventional pop structures since last working together. But old tensions resurfaced as a dramatic rift emerged with Jansen, Barbieri and Karn on one side and Sylvian on the other. Unsurprisingly, Rain Tree Crow proved to be a one-off project.

Karn resumed his solo career with 1993's Bestial Cluster that found him exploring heavier, rock-oriented material. The record’s fiery edge was significantly influenced by producer David Torn, one of Karn’s closest friends. The two went on to recruit drummer Terry Bozzio and launched a 1994 power-trio project called Polytown.

Karn’s latest solo release is The Tooth Mother. It’s his most eclectic and diverse to date in that it offers an engaging hybrid of expansive rock leanings and Middle Eastern influences from his youth. It also features his most upfront bass playing to date.

I understand you just moved back to London after living in San Francisco for a year.

Yeah, that's right. To be honest with you, it just proved so difficult to live in San Francisco and get on with work I was doing in Europe. Being in America with the time difference just wasn't happening at all. I had to move back to get things moving again. I moved to America because I really wanted to put myself in a strange environment where I didn't know anybody and didn’t have any of my personal belongings to see if it would change the way I work on a musical level. It's kind of an experiment with myself, which I think worked very well. It was a really interesting thing to be somewhere where you don't actually know anyone. Quite often when I'm working I'll put the answer-phone on and not speak to anyone for a couple of months and that's okay. I tend to kind of thrive on solitude in a way. I don't really socialize very much when I'm living in town except for say two or three really close friends. I wasn't born in London, so I've always felt a little bit of an outsider here. But when I'm actually in a place where I know nobody's going to call me anyway, it has a slightly different feeling to knowing that your friends are around. It's quite lonely, but I enjoyed that in a way. I think it made my approach a lot more positive. I also really enjoyed being in a place that wasn't cold with grey skies for those winter months. I felt much closer to nature than I guess I had for a long time. I really believe that affected me a lot. The material I've written since moving there seems a lot more happier than of late.

Tooth Mother stands out from your earlier work because of its many world music influences. Tell me about your interest in including them.

To be honest with you, I've never actually bought a CD in my life. It's a terrible thing to have to admit because I know I'm missing out on a lot of music. But the way I think of it is almost like somebody working in a bar. When they finish work, the last thing they want to do is go and have a drink. So, I tend to hardly ever listen to music unless I'm visiting friends or I'm out somewhere in a club.

One of the main influences for me is traveling. I really enjoy traveling and it stimulates a kind of imagination. Often, I write by thinking of a place and trying to imagine what pictures come up. It's an old trick that we used to use a lot in Japan, actually. We would just give each other a name of a country. And we would all go away and think about this country and then get together and try and write a piece. And I find that much more influential than actually listening to music with a purpose. It works in much the same way as when I get influenced by books that I read.

I was really pleased with The Tooth Mother because it’s so influenced by the kind of Arabic music I was listening to when I was very young. That was really allowed to come out for the first time—to the front, anyway. I think it's always been there, bubbling under. But it was the first time I really concentrated on that influence. I was expecting to carry on with that, but there doesn't seem to be much of a Middle Eastern flavor in the new music I’m working on. I can't really say that the music of the west coast really influenced me. But, I guess I was hearing it just by being out and about. Maybe that’s why the new music is more rock oriented.

Specifically, what prompted you to incorporate Arabic structures into Tooth Mother?

What triggered it is that I realized this album was going to be written, arranged and produced completely by myself. That’s something I haven't done for a very long time. It wasn’t through choice. I was actually planning to have David Torn co-produce with me, as on Bestial Cluster. But I ran into problems with the record company. To cut a long story short, the easiest way out of it was to go ahead and do the whole thing myself. So, I had to rely on my own influences much more than other people I would be working with.

I was born in Cyprus from Greek parents. Cyprus is situated in the middle of Egypt, Israel and Turkey. And my mother was always listening to Middle Eastern music when I was young. I was always being told not to tell other relatives because it was not the thing for Greek people to be doing—especially Turkish music. So, I think I grew up believing that Middle Eastern music had a certain amount of mystery to it. It was something you had to keep secret. I think that's what attracts me to it now. It doesn't have to be a secret anymore, but it still makes me feel something. Something from my youth comes back when I hear it.

For Tooth Mother, I decided to really focus on what I consider the three main points of influence that have been there since I took up music. And one of those is the Middle Eastern stuff. The other is kind of Motown funky music which was my first love. The last influence is classical. It’s not as strong as the others, but I was in a classical orchestra for a while when I was a teenager. So, it was really interesting for me to focus on those influences. It was almost a challenge to see if it could be done that way. I'm very pleased with it. It's a very personal album to me.

Western musicians often get criticized for incorporating world music into their work, no matter how noble the intent.

It irritates me that a lot of the press seems to think that it's something new. I get very irritated when the press talk about me suddenly being influenced by it on the new album, when actually I feel it's always been there. It's something that I've done for quite a long time with the other boys in Japan. Obviously something like Tin Drum was very much influenced by Chinese music. I think it's very healthy. I think it's okay as long as it is a melting pot—as long as things are actually melted down and constructed into something new. I hate the idea of stealing people's music, but I think if it's done unintentionally and with a fresh approach then I think that can only be healthy.

Did you feel comfortable producing your own music again?

I really, really enjoyed it. I think I'll probably be making the next album in that way too. I didn't know I was going to enjoy it. I was a little bit frightened of it. But I think at the end of the day, I have to admit that I'm a bit of a control freak. I really enjoyed being totally in control.

Describe your approach as a band leader.

A lot of the time the demos I work on are very, very poor quality. I really dislike developing them to a point where it sounds so good it's almost impossible to recreate when you get into the studio. So, I try and keep things as rough as possible. Quite often when I'm working with musicians—for instance, with Gavin Harrison, the drummer—I don’t play them any of the demos. I feel the quality is so bad it would be really hard to understand what was actually going on. So, generally, the way I deal with musicians is to give them a bass line and describe the kind of atmosphere I'm trying to achieve by the end of the track. Once the drummer latches on to the bass line, then I'm quite happy to carry on with the rest of the musicians. I give musicians very little to work with.

So, the focus is much more on the spontaneous than the composed.

Yes, and especially with this album in particular. Most of what you hear, except for possibly the vocals, was the first or second take of every musician's performance. I enjoyed keeping the spontaneity in their performance. I enjoyed keeping mistakes. It takes a long time to evolve to that stage. The temptation is to just try and perfect everything. I believe by keeping mistakes, the end result sounds as if the band was actually playing together. I think that's accomplished in certain places.

You don’t read music. How does that affect your ability to communicate with fellow musicians?

Well, I'm very careful to choose a few chords that I know may be in tune with what I'm playing. Those chords may eventually disappear—usually they do. But, as far as the notation of the bass goes, I don't really bother about it when it comes to working with the other musicians. I've reached a point where I don't really care if it's the right note or if it's a legitimate chord structure. I quite enjoy confusing other musicians. I rely very much on my ears. If it sounds as if it's the right thing, then I'll keep it—even if it may not be.

It was many years between Dreams of Reason Produce Monsters and Bestial Cluster. Why was there such a long gap between them?

The long break came from struggling with Virgin Records. I wanted them to allow me to make more instrumental music. It was a long-winded struggle, but it allowed me to really evolve the way I write because I had six years or so in between. The strange thing was, when I came to do Bestial Cluster, things just fell into place. There was nothing really planned. I got to know Kurt Renker, the owner of CMP, through David Torn. We became quite good friends and he let me use the studio when these other artists weren't. The idea was that when we finished the album, we would then give it to Virgin. That way, I wouldn't have to go through the arguments that I usually go through. I can just give them a finished product.

By the time I'd finished the album, Virgin had been swallowed up by EMI and everyone I knew had gone. So, I was left with this album. We decided between us—me and CMP—that we should release it on the label and try and make a new direction for the label. It obviously wasn't as jazzy as some of their artists. It gave me incredible freedom to draw on all the musicians that work on the label. I would usually time my visit to the German studio to overlap with whoever was using the studio so I could get them to play for a day on my album as well. I think I'd reached a much more confident level by the time I got to Bestial Cluster and The Tooth Mother. I'm much more confident about the way I play. I'm much more confident about the fact that there will be more albums to come. I think that's something that takes a lot of getting used to when you're writing. The panic of "This could be the last album, so I have to get everything written on it that I want to say" doesn't necessarily happen as you get older. You can take your time and wait for the next album.

You've done a lot of work with David Torn. What makes him a compelling musical partner?

He's influenced me a hell of a lot. As a musician, he's probably influenced me more that anyone I can think of, to tell you the truth. I consider David Torn my best friend outside of Steve Jansen and Richard Barbieri. He's definitely my closest friend. We're like a couple of little kids actually. We're very juvenile when we're together, but it doesn't last for too long. It swings from being very childlike and playing around with everybody else to incredibly deep, philosophical discussions. I think we're very like-minded in many ways, especially music.

I also refer to David Torn as the person who saved me as a bass player. I went through a period of not playing bass at all. I generally never rehearse anyway unless there's an ultimate goal to it—like a tour or a recording project. So, when I found myself without having an album released for a few years, I basically just stopped playing bass guitar. And it was David Torn who really pushed me back into the field of playing live on his Cloud About Mercury tour. I was forced into a position where I had to learn to love my instrument again in front of an audience, which was pretty scary. But it seemed to do the trick. He was always pushing me at that stage to make me realize the voice I had on the bass was actually a valid statement. So, he's helped a lot as far as confidence goes—especially when it comes to playing weird notes. He'd always perk up when something wrong happened, whereas I may turn around and apologize and try and get it right next time. His attitude would be "No, let's keep the mistake." So, I think that's rubbed off on me a lot. I tend to appreciate the same kind of mistakes now.

Why did you believe your voice on the bass guitar was invalid?

Well, trying to stay alive as a musician is not very easy. And a lot of the time after Japan was spent on sessions—purely to stay alive. Doing sessions is something I never really enjoyed. I enjoy doing them now. And funnily enough, now that I enjoy doing them, everybody's stopped asking me to do them. [laughs] But at the time it was always a very tense thing for me. I was always worried that people would either not like my bass line and ask me to change it, which would be very difficult for me to do in a spontaneous manner. I would also have to consider the fact that the bass didn't have to be the main melody and that it had to play the role of a bass and be in the background with the drums. I'd also spent a long time growing up with the other boys in Japan from schooldays where I was always being asked to tone down what I was playing. I don't think that's a bad thing because obviously with a band you have to consider the fact that you're trying to compose something together, rather than feature any one instrument more than the rest. So, I think it was that kind of upbringing that made me feel that it was going to be a little bit too much for people to take if the bass was so upfront. That's another reason why I'm so happy with Tooth Mother. It's the most upfront I've ever played. It's almost in your face. And people seem to have reacted to it really well. So, I think I was probably wrong in those judgments of the past.

You were very reluctant to join Torn’s Cloud About Mercury band at first. Why?

Simply because I'd received some tapes from him and I just couldn't possibly imagine myself playing with the likes of Bill Bruford and Mark Isham. I just felt that I wasn't in the same category as them and that I wouldn't be able to read the music or understand what chords they were talking about. David had been calling me for over a year to try and get me to do the Cloud About Mercury studio album. Eventually, I flew over to Germany for the rehearsals of the Cloud tour specifically to prove to David that he was wrong about wanting me in the band. I thought it was the only way I was actually going to get him off my back.

You went over to prove that you couldn't handle it?

Yes, exactly. He just wouldn't take no for an answer. I thought that the only way I'm going to get him to stop calling me is to show him I'm not the person and bass player he thinks I am. I thought that would be the end of it. I had made so many excuses. I'd made up so many stories of myself being busy doing this and that in order to try and get out of the recording. So, it had to be done. It is a bit extreme when you think about it. [laughs] But, actually, it worked in the complete opposite way. It's something that we both laugh at now.

How do you look back at Titles and Dreams of Reason Produce Monsters?

I think Titles was a kind of explosion of everything that had been stored inside of me for quite a long time. I'd become very frustrated with the way we were working as a band in Japan. For example, taking a very long time in the studio to write pieces. And, also, as a bass player working within a band, there were certain limitations I had to put myself through in regards to the vocals and things like that. I really wanted to be in a situation where the bass could be as dominant as possible. I also wanted to put myself in a situation where I wrote as quickly as possible. So, that album is really special to me because every track written on that album was recorded and mixed and then moved on to the second track. The running order on the album is exactly the same as it was written. It was recorded, mixed and completed in 28 days. So, I'm very pleased with the fact that I managed to do that.

I went through a very strange change after Titles. I think I was a little bit frightened by people saying that I was the best bass player in the world and all of those lovely compliments. But at the time I wasn't really ready for that. I don't think I could handle it very well. My reaction was to try and prove to people that I was a composer and not just a bass player. That’s how I look at Dreams of Reason Produce Monsters. There's not a lot of bass playing on that album. Looking back, I actually think that's the weakest album I've made. There should have been more bass playing on it. I think that my trying to prove to the world that I was a composer was all very well and good, but I think the way I see my bass playing now is almost as the main melody of a piece. That's something I was ignoring when I made that album. I think it suffers for that.

You contribute some compelling bass work to Andy Rinehart’s Jason's Chord. Reflect on the making of that record.

It was a very rushed album. It was kind of "Fly Mick in. Leave him alone in the room for 10 minutes. Right, he's ready. Let's record that one. Leave him alone for another 10 minutes and wait 'til he's ready for the next one." So, there wasn't a lot of time to recap on what was actually done until the album came out. When it did, I thought "Wow, that's what I actually played. That's what happened." So, it seemed to fit into the Polytown bracket where you don't have any time to reassess. You just battle on and play regardless, and see what everyone makes of it. I really enjoy working that way. I think you come up with different things that way. I really like that album. I think Andy Rinehart is a really good writer—especially his lyrics. I'd love to see him do more.

Do you think you'll make another song-focused album?

I've been very tempted. It is something that I'd like to explore again. There's a lot to be said for the pop song. It's very easy for musicians to sit around and listen to music and think "Well, I can do that. That's so easy. It's so simple. I could easily write something in the same vein." But, actually, when you sit down and try it, it's not as easy as you think at all. There really is a certain attitude towards writing pop music which, if you don't have it, it just doesn't work. So, I don't think it would be that easy for me to do that. I think once you've gone down the road of obscure music, that becomes the easy road for you. In a way, I consider what I'm doing to be obscure pop. But most people wouldn't consider it to be pop. To me, it sounds very commercial. I'm probably the only one who believes that. My friends always laugh when I tell them that the next album I've written is really commercial and very poppy, because it never sounds like that to anybody else. But Rich, Steve and I run a label called Medium. I think the pop avenue is one the three of us want to explore very much. We've known each other for such a long time but we've never actually made an album together. It seems ludicrous that we've never done that before.

What's your view on the importance of Japan today?

It's taken a long time to see the positive side of the Japan work. For a long time, I think we all would have turned around and said it’s fluff. But I'm beginning to see the uniqueness of the band now. I think the most interesting thing to me about Japan is that there were four musicians who were very original in their approach to their instruments, all in the same band. And I think that's the amazing part—we were all in the same band. It's okay if you get a really original drummer like Steve Jansen in a band that didn't contain other musicians like that. But the fact that we all evolved together and learned to play our instruments together was really quite amazing. It really made us sound kind of different from the other bands. So, I think there's some value there.

Japan’s influence continues to exert an undeniable influence on today’s pop sphere.

We're absolutely amazed to see that again we're being written about in the trendy papers in London. It's having a big influence on new bands that are coming up in Japan too. That's something completely unexpected. We really thought we'd heard the last of it. As you know, there's all this whole ‘80s thing coming back now. And the British music press seems to be basically slagging off every ‘80s band that you can possibly think of, except Japan. They're actually saying that we were the only sensible ones around, which I find really amazing, considering the way we looked. I think what put most people off initially was the way we looked. It's unfortunate that we grew up in public that way. Everyone has a past, I guess.

How did becoming so successful so young affect you?

I think it affected us pretty badly as people. I think musically, it left us in a bit of a state of confusion as to where to go to next. We really weren't expecting success on that level, so we hadn't prepared ourselves for the event of that happening. Also, the pressures that we'd had for seven years from the record company and management suddenly disappeared and everybody was turning around and saying "You can do what you want now. You're successful." We'd got so used to fighting against the record company for what we wanted that when we found ourselves in the situation where it just wasn't there, I think we began to turn on each other and fight against each other. This was our downfall really. I think as people, it took us a long time to get over the success so early because it really puts you inside a kind of bubble—one people can't penetrate through and one you can't break out of either. The whole makeup thing was really part of that bubble. It wasn't a fashion statement to us. It was almost a protection against the outside world. It became a fashion statement, but it wasn't originally. And we found that once we'd split up that we just couldn't get rid of that mask. It took a long time to stop wearing makeup and just go out and do the shopping. We just couldn't cope without that protection there.

Who first suggested the idea of wearing makeup?

I can't really remember specifically. I remember us just wanting to look different from the punks that were around at the time in the ‘70s. So, David and myself took the step to dye our hair and everything just led from there.

Do you believe the tension among Japan’s members had positive value when it came to the music?

Yes, totally—100 percent. But somehow, when we got together to do the Rain Tree Crow album, I think we believed that we'd all moved on enough for that tension not to exist—for it to be a happy working environment. That lasted for a couple of weeks before the pressure from each other started to kick in again. I do think that at the end of the day it’s quite an important album we came up with there. And I think that happened purely because of the tension in the studio.

Didn’t you largely disown the album because Sylvian reworked the material on his own before it was released?

Well, it's very hard to listen to it with open ears and an open mind without remembering the procedure. Yeah, it's very hard. I really enjoy hearing people say they like the album. It always makes me feel that there's something there that I'm not hearing. But I do think that it's an important album in that it really felt as if it was the final killing off, if you like, of the Japan days. It really felt as if it was something that we had to do before we could really move on.

The Rain Tree Crow album went significantly over budget and Virgin offered more money in exchange for the group switching names to Japan. I understand you, Jansen and Barbieri were prepared to make that compromise despite Sylvian’s objections.

The whole concept and direction of that album was that it was going to be very pop-oriented. We really wanted to surprise people by doing the unexpected—by coming back into a market which we'd left behind a very long time ago. So, we decided that we would have a new name— Rain Tree Crow. The more obscure the name, the better. We believed that it would be a long-term project and that the name Rain Tree Crow would become more important than the name Japan. So, it would be a killing off by outdoing what we had done before in the same field—the pop market. Due to the tension and the long time it took us to record that album—it took two years—it became very evident that there was not going to be a follow-up album. There was only going to be one. It also became evident that we hadn't quite made it as poppy as we had hoped it was going to be. [laughs] So, the concept changed into "If we really want people to hear this album, the only thing we've got going is the name Japan. Otherwise, people are just not going to hear about it at all." That’s why the rest of us came around to allowing Virgin to use that name. Also, it was the only way we could possibly see being able to finish the album because we'd run out of money for mixing.

The initial budget for the album was very large. It’s remarkable the group exceeded it.

We'd never really seen a budget like that before. The ridiculous thing is we learned the hard way that the more money you have, the longer you take spending it all. The album took two years. It went until we had no money left. Then we had to go back to the record company asking for more, which is really ridiculous.

David Torn said he was supposed to be part of the Rain Tree Crow line-up. What happened?

We really wanted a soloist and a guitarist. David was my first choice. I recommended him to everyone. It looked as if it was going to happen for a while. But the David Sylvian we'd always known was one of complete control. That made it very difficult for us to work with him. And that was another reason why the band just couldn't work. We found that as more time went by, the more and more control David [Sylvian] wanted to take—to the point of not wanting David Torn to come into the picture because he decided to take care of the guitar himself. That's basically what happened. I also think that—and this is really being honest now—there's always been a strange personality clash between myself and David [Sylvian]. We're very opposite in a way, which can be very healthy in a working environment. But I think the thought of getting David Torn into the studio in a situation where he and I could be strong together I think, maybe, frightened David [Sylvian] a little bit. Dealing with one person like that is one thing, but two would just be out of the question.

Even though the band had imploded, it was still obligated by the label to make a video for "Black Water."

The video was a contractual fulfillment. It's something that we had to do. It was all filmed separately. We didn't bump into each other once during the making of that video. It was all done separately, on separate days.

Specifically to avoid one another?

Yeah. [laughs]

Can you imagine a scenario in which the four of you put the differences aside and work together again?

I've always said since the end of Rain Tree Crow that it's completely out of the question. There's no way we could ever work with David [Sylvian] again. But, quite recently, I'm beginning to think it might be quite an interesting thing to do again, actually. That tension we were talking about in the studio just doesn't exist when I'm working with Richard and Steve. We're very easy-going with each other. I do think that tension, as unbearable as it may be, does produce something that is stronger than the individual parts. I do think that when the four of us are together there is something unique produced. I'd like to see that happen again. Rain Tree Crow was a huge step away from the sound of Japan. I'm really curious to see what the next step would be if we did get together. I think time has to go by us some more until we're all feeling that way. But I've got a feeling that the others are probably feeling curious about it too—the others meaning Steve and Rich. I don't know how David's feeling about it. I'm really looking at it long-term. I think there is some small possibility that maybe something might happen.

David Sylvian has been performing "Ghosts" at his recent shows.

Oh, I heard, I heard. It surprised me. That's a real shock. I didn't see the shows, but I did hear that. Very bold.

He played material from Rain Tree Crow too.

Really? That's very interesting that he did Rain Tree Crow material too—a big surprise. Maybe I'm right. Maybe he is thinking along the same lines.

Japan has yet to receive the anthology treatment. Are there any interesting outtakes in the vaults?

I think pretty much everything has been released. We've been talking about this ourselves recently. We remembered that there are some very, very old recordings lying around somewhere that were done before Adolescent Sex which we would absolutely hate anyone to hear. We were signed to a German record label, Hansa. At that time, it was basically a disco-oriented label with Boney M and people like that. So, we had to spend quite a long time in the studio to convince them that we were not a disco band—that we weren't very good at disco music. That's basically what these recordings consist of. I'd really be ashamed if anything was done with those.

Your most recent band project was Polytown—a group with a different kind of tension.

Yeah, it was very difficult. It was quite a strain. It was very, very hard going—maybe the hardest album I've ever had to work on. Bruce, our engineer, had a very hard time too. I think a lot of it was because it was the first solo album, I guess, that Terry's really worked on. It's like three solo albums in one. And I think it was irresistible for him to try and take control to a certain extent. Whereas, for David and myself, we'd made albums before and we were a lot more easy-going. So it did make things quite tense. There wasn't a lot of room for experimentation because of the time limit as well. Things may have been very different if we'd had more time. I think it's quite an odd album, but I'm really happy with it—really happy with it. The only thing I wish we'd had was a little bit more time for the mixing. I think that could have been improved on. But, the actual writing, I think, was a real feat of strength looking back on it. The fact that we actually managed to do that in three weeks is unbelievable. I really like putting limitations on myself when I work and the Polytown experience was full of limitations.

Polytown really was a big influence on me too. Working with Terry and David in a three-piece band meant that I really was pushed even more into the position of being the main melody. And David really had to concentrate on the looping, with the odd solo here and there, but basically creating the atmosphere of the pieces. So, I really was left as being the main melody which was a complete revelation to me. It was the complete opposite of what I'd always been led to believe. And the fact that it was done in such a short space of time really gave me the confidence to then go on and do Tooth Mother—not in quite such radical circumstances—but with the same kind of ethics.

Will Polytown record again?

I would really like to see another Polytown album happen, with a little bit more time. Its sounds as if I'm really masochistic, doesn't it? I like these tense situations all of a sudden. I'd also like to see it happen with a different line-up. I'd really like to see another album with myself, David and guest musicians. But I don't think it would be fair to keep the name Polytown if Terry was not there. But David and I have lots of ideas for albums together.

In more conservative rock and pop circles, there’s a real reluctance to accept the bass guitar as an instrument that carries the lead melody. What’s your take on that?

I have mixed feelings on that. To tell you the truth, when I go to see a band and there is a spot in the show where the bass solos, I find that quite boring—but not because it's a bass. I find any instrument soloing quite boring. And drum solos I feel the same about. So, if, and in the same context, somebody asked me to play a bass solo, I really wouldn't know where to begin. I'm not really a soloist. But I do think there's a lot of ground for the bass to be the main melody—to be the voice of an instrumental piece, much more than just being the underpinning. So, I'm really mixed. I'd like to think that the bass hasn't been used to its full capacity yet. I really think it can be a beautiful, melodious instrument. But I think it has to be careful not to lose its role of being that rhythmic pin. I think there's a center-point somewhere the two can meet. My big thing is rhythm. Drums are my favorite instrument. So, anything that I do on the bass has to be rhythm-oriented. But that doesn't stop the bass from being the main melody at all. I'd like to see it being used that way more.

Any theories on why so many producers, record companies, engineers, and guitarists alike seem fearful of allowing the instrument to play a larger role?

I think it's because it makes the rest of the music and the rest of the instruments sound small in contrast. Generally, what happens to me in the studio is when the bass is low in the mix then it sounds like a song should. But as soon as the bass comes up to the level that I like, the rest of the music sounds very small. [laughs] When you suddenly have something like a solo in the middle of a piece, it's very hard to give it its right dynamic power when the bass is overwhelming everything. I think producers, guitarists, etcetera are reluctant because bass is usually one of the first instruments to be recorded—along with the drums. And if it's too dominant, I think everyone else is a little bit at a loss for where to go with the music, because it's taking up a large space in the track. I think that's basically it. I think, especially for producers, it must ruin the whole concept.

Earlier, you alluded to the idea that you’ve experienced an unfavorable reaction during sessions when you played like yourself.

The music business is full of musical discrimination. It's really sad because that's the complete opposite of what music should be.

How do you cope with that sort of situation?

I would tell myself that they're probably right. You know, they're probably right in their tried and tested area, and they know better than I do. But, that's where the doubt starts setting in, you see? I think it's natural to be insecure as a musician. It's part and parcel of the job. You're always having self-doubt and it takes a really long time to reach the point where you can control those doubts and know your worth without appearing arrogant. That's the other danger—it can go too far the other way. I think that the arrogance that you find a lot in the music business is due to that insecurity.

I did a session in the mid-‘80s where I was basically asked to play exactly like a keyboard synth and that's something that really upset me. It was a session for Yello. I played on a track with Shirley Bassey. And if you do ever happen to hear it, you'll be convinced that it's a synth bass. [laughs] That session was probably a turning point for me because I arrived at the studio and there was already a synth bass on the track, which I thought sounded fine. We spent all evening basically adjusting my bass line note by note, until I was in the position where I was playing the original synth bass line. And, as I say, it really made me very angry. It was a turning point because I decided that I wasn't going to do sessions like that anymore. Obviously, they just wanted me for the name and not for the actual way I play at all, which is not what I want to do. No, not at all.

When you’re not creating music, you’re often sculpting. You’ve said that you like to keep your work in one world separate from the other. But is it possible that one art form influences the other?

Hmm. That's interesting. I think the same influence can be used for a piece of music or a sculpture. Whether they influence each other is a really interesting question. I think it's possible that a piece of music could influence a sculpture more likely than a sculpture could influence a piece of music. I think they're just so different in approach. It's very hard to find common ground, except for certain words that are common to both of them. Music can be seen as sculptural, if you like—the way it's built up. But they really are such different states of mind, you know? Sculpting is just so physical. It's so three dimensional. Music? God knows what that is! I mean, it just comes from who knows where. You can't see it, you can't touch it. It's very different.

I really love the idea of bringing them together almost as concept art. I think, then, they can work very well together. I'd love to put an exhibition together and write music specifically for it. That could work really well. I sculpt all the time and I have occasional exhibitions if I'm lucky. But I try to keep sculpture and music separate because I find that most people come to the exhibitions because I'm a musician and because maybe they've heard of my background or whatever—not because they want to see the sculptures. I think that's why I'm a bit reticent to get more involved in the art world. I'd really like to state myself more as a musician rather than an artist at the moment. Also, the art world is probably more full of bullshit than the record industry. [laughs] So, that's another reason why I don't like to get too involved.

What made you choose "Karn" as a last name when you changed it all those years ago?

Oh dear. Well, I'd always been called Mick because of my surname—it's unpronounceable. I really wanted a name that left a pause between the Mick and the surname. Because, quite often, with a 'Mick' name, it just runs into the next word—the next name. So, it sounds like quite a silly reason, but I thought the only way to really achieve that is to have the surname beginning with the last letter of the first name. And that's where it came from. I looked through phone books for ideas. At first, it was going to be "Kar" and then I thought "Well, Karn sounds even better." I had no idea at the time that it was actually an Indian name. So, it could have been anything, really.