Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

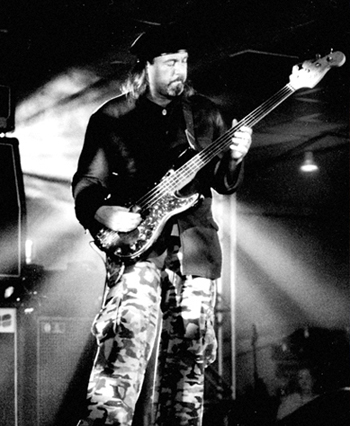

Bill Laswell

Intuitive Spontaneity

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2011 Anil Prasad.

Producer and bassist Bill Laswell has quietly been influencing the development of a wide spectrum of genres and artists since the dawn of his career in the late ‘70s. With recordings and collaborations numbering in the hundreds, he easily qualifies as one of hardest-working and most prolific musicians of our time. Laswell traverses dub, ambient, jazz, funk, rock, pop, and world music terrain with a fearlessly nomadic attitude. He’s responsible for a considerable number of important and intriguing cross-cultural explorations, many of which have been released under his own name or that of the Material collective. He’s also produced artists as diverse as Laurie Anderson, Afrika Bambaataa, Herbie Hancock, Pharoah Sanders, Sonny Sharrock, The Master Musicians of Jajouka, Tony Williams, and John Zorn. In addition, Laswell is known for album-length remix projects for the likes of Miles Davis, Bob Marley, and Santana.

Unexpectedly, Laswell had to pause his fast-paced lifestyle when he contracted spinal meningitis during the late ‘00s. He successfully recovered and is back with no less than nine new albums released between October 2010 and April 2011. One of his key current projects is Method of Defiance, a group also comprised of Hawkman, Dr. Israel, Toshinori Kondo, DJ Krush, Guy Licata, and Bernie Worrell. Last October, it put out Jahbulon, a song-based effort steeped in reggae, dancehall, and electronica influences. It was rapidly followed up by Incunabula last November, a wide-ranging instrumental record that explores drum and bass, ambient, and dub territory. April sees the release of Dub Arcanum Arcandrum, the final album in the trilogy. It’s a remix album based on material from the previous two albums, with contributions from Laswell, Lee "Scratch" Perry, The Scientist, Mad Professor, Dr. Israel, and DJ Krush.

Another important new recording is Gigi with Material’s Mesgana Ethiopia. The disc continues Laswell’s long working relationship with his wife Ejigayehu “Gigi” Shibabaw, a renowned Ethiopian singer. Mesgana Ethiopia finds Gigi performing her original songs, as well as traditional Ethiopian pieces. And given that she’s backed by Material, featuring Laswell, Aiyb Dieng, Hamid Drake, Dominic Kanza, and Peter Apfelbaum, the group seamlessly merges her vocals with elements including traditional African music, dub, funk, and trance.

Laswell discussed the making of all of these albums, and explored his many other upcoming releases in this conversation. He also provided his thoughts on getting through his health crisis, and the new perspectives the experience provided him. It concludes with enlightening reflections on past projects with Sussan Deyhim, Mick Jagger, Fela Kuti, and Henry Threadgill.

Jahbulon is a significantly more accessible effort than previous Method of Defiance albums. Describe why you went in that direction.

Jahbulon is really the first Method of Defiance record, because it’s the first one that’s been put together by the group as it is. The other albums were compilations which were more based in drum and bass collaborations with producers and other musicians. And then there was some live stuff, but that wasn’t the full band. We were still in the stage of improvising a lot more. There was less structure, focus and vocals. It was more experimental. We were conscious of making this one more accessible. It’s more focused, detailed and conscious. In every way, there’s more commitment to creating something more tangible.

Accessibility isn’t typically part of your agenda.

It would seem it’s not if you take 10 out of 20 records I’ve made. But given the opportunity, I would do that as often as possible. It doesn’t always fit the situation or the conditions don’t allow for that sort of expansion or direction. A lot of times I’m limited by circumstances and I can’t break out of certain areas if I’m dealing with a particular cast of people. But whatever particular environment I’m in, if there’s an opportunity to make things a bit more accessible, I’ll always try and take it. I welcome working in those areas. I don’t get enough opportunities to do it. When I do, it’s an equal challenge to working in other situations.

When this album came together, we realized we were focusing more on songs and vocal pieces. There was a lot less improvisation, if any, and everyone was dealing with structure, which I’ve dealt with in the past. Bernie Worrell has also done all kinds of music and been involved in successful, structured music. So we do have that experience and we relied on it to formulate these structures and collaborate with two different vocalists who have completely different approaches. A lot of our references are based in Jamaican, dub, dancehall, and reggae. Add to that drum and bass and a lot of other random elements that we don’t have on the menu or list. Anytime I work with rhythms related to dub, there are also influences from African music, utilization of noise and noise effects, and different sorts of randomly-generated components. All of that gets added into the conception of the music, and what we got on Jahbulon, for lack of a better word, is songs.

What makes the chemistry of this lineup appealing to you?

It’s been generating over time. The idea of the name is related to the drum and bass universe in which there were a lot of projects a few years ago. We were experimenting with different situations to incorporate live drum and bass elements into performances. Lots of collaborations happened, and then there was an offer to play in Athens at an art festival. I probably could have taken any group. At that moment, we were experimenting with Method of Defiance, so I took Guy Licata and Dr. Israel. We were doing the experimental drum and bass things together. I added to that group two people who came from other backgrounds: Toshinori Kondo from Japan, who works in avant-garde music, and Bernie Worrell, who comes out of Funkadelic. It was just an experiment and we liked what happened. We also liked how the audience responded, and saw that having a vocalist and frontperson really helped to generate energy. We had sort of an MC, which we hadn’t done in awhile. So we kept building on that. The music started to take its own direction, without one person saying “We have to go here or there.” With enough people from different backgrounds, the group started to create and sustain its own identity. It’s still happening and evolving as we go.

Is Method of Defiance a relatively democratic undertaking?

It’s fairly democratic. I would say everyone can contribute any idea that comes up that can be expanded on. There’s no particular leader. When there’s a vocal thing, you follow the vocalist, so he’s kind of the leader. And then there's the improv or rhythm-driven things in which the rhythm section might take the lead. There’s also a DJ that’s very strong on his own as a solo artist. So when we play live, there are moments during the set when you can hear what DJ Krush might do in his own concert.

Give me some more insight into the creative process behind the group.

It usually starts with one or two people saying “I have an idea” and then bringing it to everyone else. Then the other people look at it to see what they can contribute to it. Sometimes, someone might have a completely realized design, and in that case, you follow the design, learn it and the structure, and figure out what you can do with it. Music is generated by everyone. Jahbulon is the first of three new Method of Defiance records. Jahbulon is ten songs. The second one, Incunabula, is instrumental and totally different. The third one, Dub Arcanum Arcandrum, is a dub mix of the two, which is a collaboration with remix artists based in dub, like The Scientist, Mad Professor and Lee "Scratch" Perry. Any one of these albums taken on their own wouldn’t represent what we’re trying to do. You’d have to look across all three to understand what’s going on at the moment.

Is Method of Defiance your primary focus for 2011?

Yes. It’s the primary focus because we’ve created a label around the band that’s putting out at least six projects that are already realized. The label is called M.O.D. Technologies and we’ve also got an extension called M.O.D. Japan. From there, we’ll branch out to Europe and wherever else we can make records available. Within the label are various projects, which include a new Lee "Scratch" Perry record featuring a lot of people related to the foundation of Method of Defiance, as well as people from a lot of other backgrounds as well. There’s the live Gigi record done with Material, with Hamid Drake, Aiyb Dieng, and Peter Apfelbaum. There’s a record of Gnawa North African trance music with Mokhtar Gania with a lot of people guesting. There’s also a duet record with DJ Krush and Toshinori Kondo. They did a successful album together 15 years ago and this will be part two. Dr. Israel has at least two projects coming out, one with Dr. Know from Bad Brains, which is a vocal record more along the lines of Jahbulon. We also have a Killah Priest album and some other hip-hop records that are more street.

What does running a record label mean to you in 2011?

I’m not really running it, but I have input into it and provide my ideas. I’m hopeful we can generate income so it can be sustained. The hard part is everyone is struggling. There’s no such thing as a conventional record deal anymore. So I can’t go out and grab money from corporations anymore. You really have to do your own work. To do that, you need a few things. You need people who know exactly what they're doing, that have experience and can move quickly without wasting money. And then you need money. So you need people who know how to generate money in ways that don’t fall apart as soon as they start. That’s the case with a lot of up-and-coming labels. It’s tough. People start out very enthusiastically and gradually it breaks down because of finance troubles. I’m a member of a collective that generates the activity at M.O.D. Technologies, which involves the music, art, distribution, marketing, publicity, imaging, and live elements. We’re putting together an infrastructure to further these things without getting tripped up.

Who are the key names behind M.O.D. Technologies?

Giacomo Bruzzo, an Italian living in London, is principal to the project. John Brown and Dr. Israel, both based in Brooklyn, are other important contributors, as are the members of the band. There are some outside influences as well, including people just coming into the picture.

What made the Austria gig captured on the live Gigi with Material album special for you?

We don’t get an opportunity to put together a band that size very often because it’s expensive to travel. We did have an opportunity to bring everyone to that festival in Austria, and everyone liked the feel of it, so we thought it would be a great thing to document. We documented it because it’s a consistent band that’s playing gigs. There are various offers for 2011, including the West coast, that we’re looking into. We hope the record is an introduction to more live work that will probably be documented in sound and on film. We thought the music was relevant. It’s also rare, because we don’t have the opportunity to perform at too many festivals. It would be hard to tour this band and just play venues. It almost has to be connected to festivals.

What do you find particularly fascinating about Ethiopian music?

I don’t find it more fascinating than any other music. I have worked a lot in West Africa, and I’m also very familiar with music from Ghana, Mali, Senegal, and Morocco. I’ve also worked with The Master Musicians of Jajouka. So I was familiar with the music and history. I’m a lot more familiar now. It’s a kind of time that’s finding me pass through different areas of music, sounds and cultures. I’ve also worked a lot in Japan, but Ethiopia became more of a focus because of proximity and general activity. I did a few records related to that culture that were successful, and continued building on that by bringing in new influences.

Describe what makes Gigi special as a vocalist and creative presence.

Gigi isn’t a trained vocalist. She’s not someone who studies and works on her craft obsessively. She purely and simply has a gift. She could probably not sing for years and it would still be there. It’s probably not going to ever radically change or move from where it is. It’s a natural gift. As soon as she sings, that’s her. She doesn’t perceive working as a career. Rather, it’s someone who has this gift and when the opportunity is right, she enjoys presenting it.

How does the husband-and-wife vibe between you and Gigi affect your working relationship?

It hasn’t been any different than any other working relationship. We haven’t done a tremendous amount of live stuff. There have been things here and there, but we’ve never done more than five to 10 gigs in a row. There’s a child involved, which makes things very interesting. That adds on to the experience. It’s a good experience for my son, who’s seven, to travel. It’s like leaving home, but taking it with you. He’s had a lot of experience being around a lot of heavy situations and music. He’s traveled a lot and has benefited from a lot of diverse energy. I’m not forcing him to learn anything about music or telling him what it is or what he should or shouldn’t do. He has great contact with a lot of people. He’s been to India, the Middle East, all over Europe, and Japan. At seven, I didn’t get anywhere near that, so he’s very lucky.

Does this Material lineup operate in a similar decentralized manner to Method of Defiance?

It does because it’s also a collective. It’s a band in which everyone takes care of their own duties and place within it. We’re dealing with structured music, so Gigi brings in a melody and a way of representing the melody. Then it’s up to the musicians to choose how they contribute and navigate around the vocals. There’s no particular bandleader, even in the rhythm section, where it’s me and Hamid Drake. Together, we formulate what we’re going to do. Abegasu Shiota is half-Ethiopian and half-Japanese. He’s a good arranger because he knows the songs and plays keyboards, which are kind of the tone center of the music. The horns, led by Steve Bernstein, do their arrangements. So everyone does their own thing and it all gets fitted together. If everyone gets along, is sensible, and has enough experience and patience, and is being paid, then you have a good situation.

You recently worked with The Blood of Heroes. Reflect on your involvement with the group.

I’ve had very little involvement with it. I wouldn’t call it one of my projects. I’ve hardly listened to it. I was given some tapes, which I thought were fairly minimal. I thought Dr. Israel made an effort to bring something to it, which was a little lo-fi for me. It’s a smaller scope project and something I just played on and sent back. I guess some people like it. I’m happy it exists.

The vast majority of today’s listeners rely on MP3s and cheap ear buds to hear music. What does that mean to you as a producer of such expansive work?

It means people are not listening to anything outside of those small headphones and probably aren’t paying attention to life as it goes by. I don’t listen to MP3s and I’m not part of that world. I try to make things sound as good, clear and big as possible. Sometimes the music is dark and threatening, sometimes there’s a lot of light. I’m not caught up in a technology system or trends and formats. I don’t have any knowledge about that stuff and never plan to. From what I’ve heard, the quality of most everything in the MP3 world is rather dubious and I’ve never bothered to experience it. I do things a different way. I’m just really interested in sounds and if I can hear them well, then I’ve done something I can probably be happy with.

What’s your perspective on the so-called mastering loudness wars?

I’m a little out of touch with it. For me, mastering means cutting something as hot as possible, hopefully with a lot of level and bottom. That’s not going to get reproduced in certain situations like MP3. That’s why I don’t listen to those lo-fi technologies, for lack of a different term. I can’t imagine experiencing music under those conditions.

A lot of people were extremely worried about your health in recent times. What can you tell me about what you went through?

I’ve lived fairly recklessly from day one and never really had any health issues. I never had a serious drug addiction or anything that took over what I was doing. But after a point, with so much activity, travel and abusing myself, I hit the wall. I had to stop everything I was doing and refocus. I basically had a bone infection, which meant my bones were brittle, breaking and I was falling apart. There was a lot of pain. I had to deal with painkillers and they’re very trendy right now, but they’re also very addictive. Between painkillers and drinking alcohol, I should have died, but I didn’t. There was about a year where it was really hard, because I couldn’t operate at the level at which I needed to operate. I lost a lot of time. I guess it’s nothing compared to what some people have to deal with. It was on and off for about a year with this struggle which is now resolved. But yeah, there was a moment when if I hadn’t addressed things when I did, the situation would have been terminal. It was at its worst two years ago and it gradually got better and better. I had a lot of help from people who were conscious of trying to do things differently through acupuncture and very special, private doctors. I also had a lot of financial help from people who’ve always been there to help like Chris Blackwell, Giacomo Bruzzo and Steven Saporta. I was able to deal with all of it and get through it without suffering financially or losing anything.

Have you altered the intensity of your work style in response?

I’d say so. I’m more relaxed, focused and open. I’m over the bump and conscious that I can’t keep going in one direction without registering some kind of sensible moderation of my activities. After going through this, I’m grateful for the amount of living I’ve done and realized that it could have all went away. Even if that happened, I would have left quite a lot of things behind—contributions and activities that were documented. But I realize that’s nothing compared to what’s happening in the future. I’m always at the beginning of what I’m doing. Sometimes I’ve heard that one thing I’ve done has changed someone’s life or someone’s said because of this one thing I did, they now do something differently. Some people have also said something I’ve done was horrible and made them want to stop living. [laughs] All of those statements are about the same music. But having done enough things, I know they can’t all be bad, so there have to have been some things that matter.

Are you focusing on bass playing in a major way again?

I always have, but I don’t approach the instrument like a virtuoso player. I use it as a tool to express ideas. My ideas are the kind that I don’t need a lot of technique for. I just need to be there and available to commit to the ideas and deliver them as best as possible. I try not to be too analytical about it. If I can be fairly lost in the instrument, it can be more magical and have a sense of mystery, rather than a sense of structure. I didn’t pick up the instrument to get into comparisons—like when people try to play like someone else, compete with other players, or do something to make money. I do it for a reason that’s not explainable with words.

Do you consider your bass abilities a gift, akin to Gigi’s vocal talents?

Yeah, I guess it’s my gift and it has to do with intuition, spontaneity and a certain amount of will. It doesn’t direct itself or detail itself toward one particular facility, function or craft. It’s an overall obsession. It also has its own self-destruct system along with its own sense of protection, which keeps it alive for me.

As we did in a 1999 interview, I’d like to throw out some album titles you’ve worked on, and have you respond to them with whatever comes to mind. Let’s start with Massacre’s Killing Time (bassist, 1981).

That album came out of the moment when I had just connected with Fred Frith. He was clearly the leader of that group. Fred Maher, the drummer, was really young, like 17 or 18. He didn’t always know what he was playing, but he played it with a lot of conviction, which Fred liked. There was youth and almost a punk feeling to the band. Fred Frith was coming to me with a lot of structured music that I wasn’t familiar with in 7, 5, or 6/8. Everything I was playing up to that point was mostly based in 4/4 time. With Fred, I had to learn all of these patterns and structures, which became a huge influence on how I did things. Once we learned the structures, we tended to throw them out and improvise, but with the idea of the structure in mind. It was kind of a first with me. With that record and band, we were introducing what other people later on, in a more sophisticated and developed form, called math rock. I thought we were at the beginning of improvised rock music. We used structure as language and had a kind of invisible repertoire without calling anything a song or a piece. It was a very important experience.

Genji Sawai’s Sowaka (producer/bassist, 1984).

It was probably one of the things I did because I really wanted to work in Japan. I had a friend called Aki Ikuta, who is a catalyst, producer and raconteur. He was quite effective at putting things together, so he hooked up a session. A lot of the Japanese sessions came together because I needed money to go to Japan. I just wanted to go and needed a reason and pocket money. So I’d work on the project to finance the trip. Sowaka probably came from Aki, who said “Here’s some cash. I’ll get everybody paid and we’ll make this record.” I don’t remember the music, but it was more based on paying for my time in Japan than anything. Hopefully everyone had a good time. I did a record with Genji in 2002 with Hoppy Kamayami and Hideo Yamaki, who is one of the great drummers of the world, under the band name U.M.A. (Ubiquitous Musicians Association) called JA-CK in 2002. It was another one I did just because I was in Japan. A lot of projects happen like that in Japan and people mostly only hear about them over there too. Every time I get to Japan, I feel like I’m home, and as soon as I leave, all I can think about is trying to get back there. I’ve been going to Japan since 1983 and there have been at least 300 trips to date.

Fela Kuti’s Army Arrangement (producer, 1984).

That was on Celluloid. Jean Karakos signed Fela and licensed his stuff. At that point, I was quite disappointed with Fela’s music. In 1970, he was on fire, but Nigeria itself was on fire then. Everything that was coming out of there was really intense, and Fela was at the head of it. I thought he had a great band then. Gradually, over time, the band started to fade and dissipate. Fela’s focus became more on political jargon, posing and positioning himself as whatever he meant by “The Black President.” He had 20-some wives, smoked a lot of pot and his priorities shifted. Music was no longer his central focus. I never thought Fela was a great musician anyway. To me, Afrobeat is one rhythm that’s loosely Afro-Cuban music mixed with James Brown. I don’t hear it as being a totally Nigerian or African music. It’s a hybrid of different influences, and Fela’s take on it was pretty fundamental.

Fela was coming to New York and I was supposed to mix the record. Fela recorded it with Dennis Bovell in London. I thought it wasn’t a great recording. Bovell was a great dub producer, but this wasn’t anything particularly unusual and the playing wasn’t great. When I got the tapes, Fela was leaving Lagos and was put in prison for carrying an amount of money you weren’t allowed to take out of the country. At that point, Nigeria was trying anything they could to catch him and bust him. They used this to imprison him. So the tapes arrived, but Fela didn’t. I took the tapes, which weren’t great, and added musicians to them, sort of in the blasphemy tradition of Alan Douglas who put The Knack on Jimi Hendrix records. I had Sly Dunbar, Bernie Worrell and Aiyb Dieng play on it. Today, if I received some dodgy tapes, they might be the same three people I’d call. So I put them on and mixed the album and that was that.

When Fela got out of jail, there was a big controversy. He said “You messed up my music. It isn’t African.” My response at the time was “Fela’s a prick. His music is shit. It used to be great. Fuck him.” It was really harsh and we went back and forth. It turned into a comedy. A year or two later, I met Fela again in New York and it was totally cool. He was starting to fade at that time. His health wasn’t the best, but I thought again about him in the ‘70s when he was a really powerful, tight and interesting presence. But it didn’t evolve. I know the guy who created the Broadway musical Fela! I’ve seen it a couple of times. It’s a great show and story, even if the music is a little fundamental.

Mick Jagger’s She’s The Boss (co-producer, 1985).

That was something I had to do just out of curiosity. At that time, I had worked with Herbie Hancock. He had a so-called hit record with “Rockit” which meant I got weird calls from all different areas. Yellowman had me work on "Strong Me Strong" which was a huge success in Jamaica and the Caribbean. At that same time, I worked with Laurie Anderson on Mister Heartbreak, which is where I met William Burroughs. Mick Jagger was also making the rounds on who was doing the hippest and most diverse stuff. I’m sure I was on a list of 10 people who were flavor of the month. Herbie’s thing was very big right at that moment, so I got the call from Mick’s office asking if I was interested in making a record. I was without hesitancy because The Rolling Stones represent a big history. I didn’t know much about them. I didn’t particularly listen to them when I was a kid. I was probably listening to Hendrix or Cream instead, but not so much the Stones or Beatles.

So I went to Nassau to Compass Point Studios and Mick was staying at Chris Blackwell’s house. I took DST with me. I thought “If I’m going to Nassau, I’m going to have to bring a DJ.” [laughs] It was pretty much comedy during those sessions. D and I goofed around, didn’t do anything serious, had a couple of meetings that made very little sense, and I assumed it was over. We met Mick at Chris’ house, and then managed to get locked out of our apartment and had Iron Maiden break into our room for us. It was mostly fun. On the last day, Mick came and picked us up and said “When should we start?”—just like that? I said “Oh, so we’re doing this?” And he said “Yeah, let’s do it. Which musicians do you want to use?” I picked Sly and Robbie to start. He wanted Jeff Beck, which I thought was a good idea. And we grabbed a bunch of people, went to Nassau again and started.

It was a learning experience, and I would have to say, a job I wasn’t ready for. It’s also not the kind of job I really wanted to do again, no disrespect to Mick. He was quite generous with me and fairly intelligent throughout the project. People say negative things about him, but I tend to say he was actually okay with me. I think the album had 12 songs. I produced six and Nile Rodgers did six. I did all three singles. I don’t think they were great, but they were picked as singles over the other stuff. I then got the offer to do the next Stones record, which was going to be in Paris. Right before I went to Paris, I got a call from Yoko Ono. I went to meet her and thought “This is going to be a lot weirder, a lot quicker, and it will pay a lot more money.” So I didn’t go with the Stones. I went and worked with Yoko Ono on her Starpeace album instead. I didn’t want to spend the next two years in Paris watching people trying to stand up and play cards or whatever they do when they make these records that take so much time to make.

Henry Threadgill’s Too Much Sugar For a Dime (producer, 1993)

I really admired Henry’s integrity and daring approach to composition. I always thought it would be great to hear him make a record with a real budget. Up until then, I thought he probably never had a decent budget. At that time, I had Axiom and went to one of Henry’s gig with Alan Douglas. Henry was playing pretty complicated music, but music that people responded to in a positive way. So I said “Let’s make a record. I’ll get a budget.” And I got a real budget. Around that time, Henry was moving to India and we had enough money to make the record, pay the people, and he even had enough money left to buy a house in India. So it made a change for him. I did three more albums with Henry later on with Sony. It’s a miracle that Henry was on Sony. I thought those records got weirder and weirder. The one I really like is Too Much Sugar.

Sussan Deyhim’s Shy Angels (reconstruction and mix translation, 2002).

That was a remix project. I approached it being conscious of atmosphere and ambience. I’m a little out of touch with what it sounds like, but I can imagine it sounds like it’s floating in space. I’ve worked on and off with Sussan for years. That’s the only time I did a full record project with her. It was a reexamining, remixing or restructuring of music that was previously done. She has a very interesting tone and is a very good improviser and presence. I recently did a track with her that also has Mark Nauseef and Kudsi Erguner coming out on in February on a record on Meta titled Aspiration. It’s a great piece. She sings a really dark vocal and we perform this downtempo dub stuff with Nauseef playing what sounds like Chinese drums and cymbals. It’s really haunting. The album is a compilation of so-called devotional pieces. It has music I made with Nils Petter Molvaer, Zakir Hussain, The Dalai Lama, Santana, and Alice Coltrane. Meta continues to slowly and occasionally put out stuff. It’s closing in on having a sizable catalog.

Tony Williams Lifetime’s Turn it Over (Redux) (mix translation, unreleased, 2007).

In a way, this represents what I wish would have happened when they did the record initially—had a proper record with a proper producer. The original album was total sabotage from day one. It was the wrong company and the wrong everything. Unfortunately, the company threw away an incredible musical statement, which to me is the most relevant in electric music. It’s instrumental music that’s aggressive, musical, adventurous, and futuristic. It was very badly recorded, and no-one cared. I was glad to get the project and I think it sounds a lot heavier now. Tony never got to hear it. I did it after he had passed. That period meant a lot to him. It was a real point of bitterness because he got dogged. Tony was the one who had the real vision on Emergency! and Turn it Over. It was before Return to Forever, Weather Report and Mahavishnu Orchestra. It’s the real jazz-rock.

In Praise of Shadows (Sony classical catalog reconstruction and mix translation, unreleased, 2007).

The opportunity was there because I had done several full-length album remixes for Sony. Steve Berkowitz, a Sony executive, came up with the suggestion. He said “I want you to try this.” He had a couple of reference points and I had access to the catalog. I didn’t deal with multitracks or anything. I just got tons of CDs and I started to edit them, EQ them differently, change things around, and put things together. It took a minute. It came out as one big piece of music. I’m totally into it. I doubt it will ever come out because I don’t think they’ll ever be able to get the clearances. If someone could get the clearances it could happen, but Sony isn’t in a place to sell records anymore. Sony Legacy is pretty much the Miles Davis label now. As for the rest of the catalog, I’m unclear what they’re doing, but they seem to be falling apart on all sides.

What’s the status of the Axiom Records back catalog?

It’s at Universal right now. I’m building a label now and if it continues the way it’s supposed to and we generate enough income to sustain a bigger catalog, then I’ll move it over here. It’s a 30-some record catalog and we need an internal infrastructure in which we don’t just have CDs sitting in warehouses. They have to get to people. So we have to figure out the distribution. That’s what we’re working on now. A catalog that large is a lot to take on. The Axiom catalog is like the Ark of the Covenant. We know it’s there and who’s guarding it. I’d like to remaster and repackage the albums. There aren’t really anything like bonus tracks, which everyone is trying for these days. All of those records were precisely made and when that happens, there’s no excess.

Prior to Axiom winding down, there was talk of a Tabla Beat Science album with John McLaughlin and Santana.

That had to do with a deal I had with Sanctuary for five records. We proposed Santana and McLaughlin and everyone was into it. Then the guy I was dealing with at Sanctuary disappeared. Crazy shit was going on over there and Sanctuary fell apart. I got paid on all of those unmade records and used the money to make other records. The only things I did for Sanctuary were two dub mixes of reggae stuff from the Trojan catalog. Tabla Beat was supposed to be one of those records. Another was supposed to be Praxis’ Profanation. That only came out in Japan initially, but just came out on M.O.D. Technologies as well for the rest of the world.

Are Praxis and Tabla Beat Science acts that could reemerge?

I doubt it. I think they’re like closed chapters, but fairly well-documented ones. Tabla Beat happened at a moment in time and made its statement. To bring it back would mean redesigning the whole thing. I don’t think anyone in the collective has the energy, vision or time to do that. Sultan Khan is older now. Talvin Singh mostly stays in India these days. Zakir Hussain is constantly working. And I haven’t talked to Karsh Kale for a long time. I hear he’s in India a lot too. The same thing goes for Praxis. Buckethead has mostly been performing solo. He also had a health issue recently with his back, so he hasn’t been that active. If you want to do something new, there are better things to do than going back to something you did years ago and starting it over.

What other projects do you have coming up?

I recently played in Japan at a gig called “Bass & Drums.” The first set was with Tatsuya Nakamura. The second was with Hideo Yamaki. It was nothing but bass and drums. You can’t really hide in a situation like that. It was really challenging and interesting. We made a record out of that also called Bass & Drums which will come out in Japan in March on the P-Vine label. I hope it will leak over here somehow. I did another noise record in Japan with kids from a new generation, including Muneomi Senju, Yoshio Otani, and Murata. They’re moving in the direction of people like Otomo Yoshihide and Terumasa Hino. That one also comes out on P-Vine in Japan in March. Also, every year for the last four years, I’ve done this event called Tokyo Rotation. This year we’re trying to get into a bigger venue with bigger names and audiences. The event has been growing and we’re eventually going to document it with a DVD and audio, and turn it into a box.

I’m also really musically keyed into doing duets with John Zorn. They’re short, but they say a lot about what we’ve done. It’s like putting two histories together. The last few things we’ve done have really worked. I’m hoping we’ll record a few of those. There's another album coming out in March on Tzadik with David Solid Gould called Dub of the Passover that connects dub and Jewish traditions. Another thing I did recently was a killer math-metal album with an amazing drummer named Morgan Ågren from Sweden and Raoul Björkenheim from Finland. We did an amazing trio record with half of it written and half of it improvised.

You once said “I think it would be really helpful to destroy the majority of music that’s existed—that way people would be forced into new ways of thinking.” Elaborate on that.

[laughs] I come and go with those sorts of aggressive takes on things. Maybe it had something to do with an enormous hangover. But why not? I read a great thing someone once said that went “I would throw out every chord and every memory if I could just have a glimpse of what’s coming in the future.” It’s pretty much the same idea: get rid of stuff, it’s in the way. What’s fortunate though is that by some great miracle, A&R people are all being terminated. So the A&R dickheads that were controlling people’s lives by making bad decisions 99 percent of the time are all meeting their maker. They’re going away, which is phenomenal. So many companies are closing too. They were all full of too many A&R people, too many bullshit middle people, and they’re all running for the hills. The truth is there are too many bands playing the same song. There are too many mediocre musical ideas. The majority of it should go away. I’ll stick with that. Not that I have a solution. I can’t replace all of that with anything, but I can try. That’s all I’ve ever been doing: trying.

All photos courtesy of Maarten Mooijman.