Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

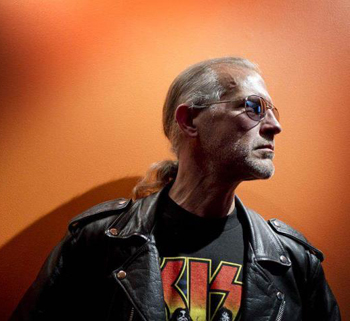

Men WIthout Hats

Recapturing the Rhythm

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2012 Anil Prasad.

Men Without Hats may be best known for its 1982 global smash hit “Safety Dance,” which continues to show up in a wide variety of pop culture and commercial usages, but the act’s experimental side has also proven highly influential. During its ‘80s heyday, the then Montreal-based band was celebrated for its combination of minimalist, percolating analog synth sounds, kinetic drum machine-based rhythms, and addictive songcraft. Taking inspiration in equal parts from Krautrock, prog-rock, disco, and the early ‘80s burgeoning electronic music revolution, the band carved out a unique and enduring place for itself in the annals of pop history.

In 1991, founder, lead singer and songwriter Ivan Doroschuk put the band on pause, following the release of Sideways, an unexpected, synth-free, guitar rock Men Without Hats album. A solo disc, The Spell, followed in 1997, after which Doroschuk largely stepped back from the music business to focus on family life. An underground Men Without Hats studio release emerged in 2003 titled No Hats Beyond This Point, after which another hiatus began.

Now based in Victoria, British Columbia, the group reconvened in 2010 with its first live performances in 19 years. Doroschuk remains in the driver’s seat, along with an all-new lineup of supporting musicians, including keyboardists Lou Dawson and Mark Olexson, and guitarist James Love. Men Without Hats’ reactivation kicked into high gear in 2011, with an extensive, successful North American tour. It provided Doroschuk with the momentum and inspiration to write and record the new Men Without Hats album Love in the Age of War. The disc proudly harkens back to the group’s original sound, using it as a springboard for some modern societal observations, as Doroschuk explains in this conversation.

Tell me about the beginnings of Love in the Age of War.

When we started up the revival of Men Without Hats last year, it wasn’t to do a new record, but to go out and tour, playing our catalog for fans who had been waiting 25 years to see us. During the tour, crisscrossing North America with The Human League and B-52s, songs just started coming to me on the bus. I had an iPad and started writing the songs. When we finished the tour, I had an iPad full of songs and my manager said “Let’s go do it.” Initially, we only wanted to do an EP, but the songs kept coming. As we were recording, I kept writing more and more songs. We ended up having a lot to choose from. We did one session before Christmas 2011 and then booked another one in January of this year. It was really organic and the project had a life of its own. It just grew and grew. It was really good and so much fun.

What do you consider the sonic signatures of Men Without Hats and how did you recapture them on the new album?

Drum machines, including the LinnDrum, and the pulse bass are a couple of them. Dave Ogilvie, who produced the album, and I, consciously wanted to make a record that was sort of a follow-up to Rhythm of Youth, our first record from 1982, because even by the time Folk of the ‘80s Part III came along in 1984, the sound was starting to change. With Pop Goes the World in 1987, the industry changed, as far as technology goes, with sequencing and computers starting to make appearances. Pop Goes the World was a lot more symphonic and orchestral, and that’s what we set out to do and achieved. But this time, we wanted to make something that sounded like it was made the week after “Safety Dance.” So, we went out and bought the synths we used back then. There were some soft synths on the record, but the bulk of it was made with analog synthesizers, with everything played by hand. There is very little sequencing going on. We loosely pretended we were working on a 24-track machine, because that’s the way it was back then. There wasn’t the “infinity plus one” number of tracks you get with computers and virtual recording these days. Back then, there weren’t any MIDI disk backups or 20 different synthesizers available. You had to make sure you were putting down a good sound because it was taking up 1/24th of your tape. That’s the spirit we went into this album with, and subsequently, it sounds closest to that original period of Men Without Hats.

Dave was amazing as a producer. He’s from Montreal as well. We had never met before, but led these parallel lives in that we knew the same people. He co-produced a Doughboys album, the band my manager John Kastner was in. John was the one who suggested him. We tried him out and recorded the album at Mushroom Studios in Vancouver. It’s a place with great history. The whole thing was very relaxed.

What motivated you to time warp back to the Rhythm of Youth sound, given all of the varied directions the band went in across its catalog?

Like you said, we changed every time we did an album. I was curious to see what it would sound like to try this approach, especially given that those sounds have made a resurgence in modern music. Rhythm of Youth was the big bang period of Men Without Hats, which also made it cool for me to revisit. The 2011 tour was so much fun because it was the first time I had played my catalog like that. We learned way more songs than we could play in a night, so we were able to change the set list around all the time and play different songs in different order gig to gig. When Men Without Hats used to tour, the tendency was to want to play our new music all the time. We really didn’t want to play the old stuff. Also, this time, there was no record company in the back, pushing an agenda. We had no record to promote, so we could play whatever we wanted. We played mostly music from Rhythm of Youth, Folk of the ‘80s Part III, the first EP, and Pop Goes the World. There was nothing from Sideways, The Adventures of Women & Men Without Hate in the 21st Century, or No Hats Beyond This Point. We concentrated on the stuff most people know us for. The truth is, as we changed, a lot of listeners drifted away. The whole scene was changing. And as the ‘80s were coming to an end and the ‘90s were starting, synthesizers became persona non grata. Since then, they have been totally rehabilitated. So, everything came together for me on this album. It was like my whole life led me here and everything kind of fit. It was a cool and unique experience.

What evolution as a songwriter does the new album showcase?

It’s a lot more intimate and personal. I’m being a lot more open about myself than I’ve ever been. Early Men Without Hats lyrics can be interpreted in a lot of ways. There’s a lot of imagery going on. The new album explores much more personal issues, with a lot of the writing fueled by my divorce. I split up with my second wife a couple of years ago and it was a great experience in that we love each other more than ever now. Everybody is happy, including our son, and everyone gets along. I was lucky. It was a catalyst for this album. It made me start writing again. I was writing more about what was going on around me while I was sitting on the back of the bus last year. I said to myself “I don’t want to make another record unless I have something to say.” I think I was able to touch on something in songs like “Head Above Water” and “Love in the Age of War.”

My manager chose “Head Above Water” as the first single, and it’s a really good introduction to the album’s theme of how we’re all in this together. I think everyone is trying to keep their heads above water and pay the rent or mortgage, keep our jobs, and keep our families together. For “Love in the Age of War,” the concept was talking about the general unease that seems to be going through society. People are asking themselves “What is the real point of life? Is it about worshiping a shiny rock or is it about something else?” That’s what the song is about. Look at the Occupy movement. I’m from Montreal and was back there recently and there was a student revolt going on, in which students were joined by their families, including parents, grandparents, and little brothers and sisters. It was one big peace movement. While I was in Montreal doing promo for the album, it reminded me “That’s ‘Love in the Age of War’ right here, marching down the street.” With Pop Goes the World, I was inspired by the birth of the Green movement. Things were starting up in that direction and those messages are still valid today. The other thing that made me realize it was a good theme to explore was my son finding out about “Safety Dance” through the Crazy Frog video on the Disney Channel. It seems people still want to be told “they can dance if they want to” and hear it across generations.

Give me some insight into the contributions of keyboardist Lou Dawson and guitarist James Love on the record.

James plays guitar, Louise plays keyboards and sings. It’s like “Johnny plays guitar, Jenny plays bass” from “Pop Goes the World.” I was introduced to James through a fellow musician who knew I was looking for a guitar player. James has been working as a professional musician since the ’80s. Louise was suggested by my manager John Kastner. He’s based out of LA and suggested Louise would be good. She and Lukas Rossi were doing a duo thing, previously. She came in, auditioned and got the job. Their contributions can be heard on the album and that’s it. It’s great fun to be in a band again. It’s made it easy to write songs. However, the creative process, historically, has always been me. It’s been that way since the beginning. There haven’t been any collaborations in the writing, ever.

Your brother, Colin Doroschuk, performs on the album. Describe his role.

Colin’s contribution is the same as always. Whether he plays live with us or not, he’s always been contributing to the records. He did background vocals on the new album. I always work by myself, but Colin is the guy I always run my lyrics and songs by. I’ve done that all my life through every album. Colin has been writing operas and working in the classical world. Out of everybody, he’s been the closest, longest-standing band member. It’s good to have him there.

You’re operating in the independent universe, after a career mostly spent with major labels and A&R people. Is there a certain freedom in that?

Oh yeah. The industry is completely different and it’s really fascinating for me. For awhile, I was out of the loop. I was a stay-at-home dad for the last 10 years and pretty much not doing music at all. I was listening to a lot of music, but not really participating. Now, getting back into it, I see the whole way music is delivered and sold is changing. It’s funny, my first couple of records didn’t even come out on CD, yet the new album is coming out on vinyl. Nowadays, people don’t have to buy a whole album, and they can buy one song. It’s like a 45 RPM single. The Beatles started out by putting out 45s. Then they’d put 10 singles on an album and sell the album. That’s how albums were born back then.

It’s weird to compete in a world where everyone who has a laptop or computer has a recording studio. It’s interesting in that the power is more in people’s hands. Labels have also been bypassed in some instances. We’re in a transitory period. With the vinyl resurgence, maybe things are also going back a bit to the old ways of doing things that work, but really, we’re in an era of society in which they have us buying stuff that doesn’t really exist. Our music, films and books are in the cloud. So are our bank accounts, games and everything else. I wonder how long that’s going to fly. People like to hold things in their hands. If they’re going to work so hard, they want to have something to show for it. If it’s going to be invisible, are they going to work that hard for it? I believe that’s part of the malaise the industry is facing. People are saying to themselves “Why would I kill myself working so hard for something that doesn’t really exist?” I think that’s why some people are starting to go back to vinyl and big sound systems with large speakers.

I don’t want my whole life in my phone and neither do some other people. I understand that you can have all your music there, but the reduction of quality you have to put up with to have everything in your phone is significant. Sure, you have your whole music library in there, but it sounds like crap. I just heard a Canadian artist talking about how he spends all this time in the studio, and hundreds of thousands of dollars working with gear that costs millions of dollars to make sure an album sounds great, and then people listen to it on their phones compressed into nothing on MP3. It’s a bit illogical, but things are cyclical and will keep changing.

Having said that, technology makes everything so easy now. We did a photo session for the new album and took 300 pictures. We looked at every one of them right away, then sent them to LA to our manager. He picked out 10 and sent them back. Within a half-hour, they were on our website and Facebook page. When we were in the studio, we would email our mixes back and forth and have an answer back in five minutes like “It has too much bass, fix it.”

Former Gentle Giant front man Derek Shulman was your A&R man during the Pop Goes the World era. Reflect on his influence on the band.

Derek had a very big influence on Pop Goes the World. We were his baby. He signed us, and he and I put the whole thing together. When he signed me, I moved to New York, just to be there. I wrote most of the album in New York and it was fun. He and I could relate on a lot of different levels. He was a lead vocalist in a band that I admired. He was one of my heroes. Gentle Giant was a progressive band that not everyone understood and he had his brothers in his band, just like me. He knew Montreal and spoke French, so we connected on a lot of levels. He had been on both sides of the fence. He had been an artist, and then he went to the management, production and record label side. He had a good vision for the whole thing. He was the person I turned to who would say “You need this and that.” When we had mastered the record, he heard the final mix and made me go into the studio to add a string line that wasn’t being heard enough. He felt the part was weak and needed beefing up. He told me what kind of thing he wanted me to write and we flew it in during the mastering stage. He was also the guy who brought in Ian Anderson to play flute on the album.

What was it like to work with Anderson?

He was great. A consummate professional. I had heard he was a really good musician and he turned out to be just brilliant. You never want to tell a guy like that “Hey, you did it wrong." So, I was really kind of nervous before he got there. All the flute parts sounded similar on the song “On Tuesday” he played on, but every part was actually different with little changes, inflections and notes held longer than others. It was more complicated than it sounded. I was concerned because there was no sheet music written down. He had to learn things by ear, and he came in and whipped it out, man. I just couldn’t believe it. He got every little subtlety. It was great. All he asked for was a six-pack of Grolsch and a Bentley to drive him to and from the train station, and that was it. The whole thing happened in one afternoon. It was awesome.

Prog-rock was a big influence on Men Without Hats. Describe the extent to which it shaped your sensibilities.

I’ve always felt that New Wave was a combination of ‘70s prog-rock and disco. New Wave was prog-rock with a disco beat. That’s all it was—Genesis with a disco beat. I was front and center for the disco movement. Also, synthesizer music, especially Kraftwerk, was a big influence. I remember the first time I heard Kraftwerk. It was the Autobahn album on Montreal’s CHOM-FM in the middle of the night. It was back in the days when they would play whole sides of records and never tell you what it was. I heard this band and it kind of changed my life. I didn’t know who it was. I would listen to the station every night and finally heard it again and they said who it was. I went down to the record store to find it. Kraftwerk was the link between prog-rock and the New Wave movement. You could almost dance to their early music. Some disco places would even play that music.

Was “Freeways” influenced by Autobahn?

Oh yeah, definitely. It was my homage to Kraftwerk. It was directly influenced by Autobahn.

Sideways is a unique album in Men Without Hats’ catalog, with its focus on guitar rock. How did that shift in direction come about?

I look back very fondly on that record. All of the albums have been an adventure to make, but the new album and Sideways are the two most fun records I’ve made. It was organic and grew out of a bunch of guys getting together after the bars closed and jamming. I realized this would be an awesome band if it had some good songs. So, I started bringing songs to the table and they were interested and said “Yeah, let’s go for it.” It grew like that. It was a period when we needed to deliver a contractual obligation record. At that point, we had already been kind of dropped by Polygram. They were dropping us because the budget for The Adventures of Women & Men Without Hate in the 21st Century was so huge. We recorded that one at The Hit Factory in New York and it was a big, expensive record. I demoed up Sideways anyway and went to Corky Laing, the A&R guy at Polygram at that point, and told him “Instead of dropping us, we’ll just make this album. Leave it to us. We don’t need that much.” We made Sideways for half of the budget we were supposed to get. We had a great time making it and everybody got paid. It was a fun time and the record company knew nothing about the album. What was even more hilarious is that it was the beginning of the ‘90s and the label could not understand the whole thing. Even fans didn’t understand what we were up to. [laughs] So, there was no pressure. It was doomed from the beginning, but we had the feeling of “We can do whatever we want, because it’s not going to really matter.”

How did fans react to such a dramatic change in sound?

I got very little negative feedback on that record. A lot of fans liked it. A couple of fans said it wasn’t Men Without Hats. I still get a lot of people coming up to talk to me about Sideways. It got played a lot at Foufounes Electrique, a club in Montreal, for instance. The industry wasn’t prepared for us to do that yet. It was right at the beginning of ’91. Had it come out a year later, people would have accused me of jumping on the grunge bandwagon, but the people at the label would have been more prepared to market a record like that. They would have heard that sort of thing on the radio and realized that was what people were listening to.

The Adventures of Women & Men Without Hate in the 21st Century was also a different album with it’s expansive, psychedelic approach. How do you look back at it?

We were just experimenting all the time. The band had really grown. It was up to eight members. The Pop Goes the World tour, in which we did 60-70 shows across North America, was a really big show, production-wise. In the 21st Century took things as big as they could get. There were a lot of tracks on the record with a lot of stuff going on. I think Sideways was a reaction to that.

You looked like you were having a genuinely good time performing the catalog on tour last year. What kept it fresh for you?

There was the fact that I hadn’t done it for a long time. There was also the reaction of the people who came to see me. I was overwhelmed. It was just incredible to see all of these people so into it. It means so much for them to see Men Without Hats. “Safety Dance” and “Pop Goes the World” have taken on a life of their own and I sometimes feel it’s almost my duty to go out and play them. There’s almost a responsibility there. It’s not something I realized before, so I was happy to be able to still deliver after all these years. I still want to do it. I enjoy it and love it. I feel so at home on stage. I still remember the first time I was on a big stage. It was when we opened for XTC at the St. Denis Theatre in Montreal. The thing that struck me was how comfortable I was and how I felt like I was at home. That’s still how it is. With the added bonus of age, I don’t feel as much pressure on me. I feel like my work is mostly done. I’m not a 20-year-old trying to prove myself. I can take the time and energy I spent back then proving myself and expend it on having fun with the music, exploring it even more, doing a great show, and being totally relaxed.

Do you consider Men Without Hats an ongoing project beyond the new album and tour?

Yes, I would like it to be. I’m already writing new stuff. As long as we’re in a Men Without Hats format, I can see my creative juices flowing. Hopefully, we can do some newer stuff than the album at the upcoming shows this year. When we stuck “This War” in our set last year, which is a song on the new album, only the oldest Men Without Hats fans knew it wasn’t an old song. It fit right in there, so that was good. I’m hoping people will feel the same about the newer material.

Men Without Hats has quietly influenced a lot of musicians. Do you see yourself as a pioneer?

I don’t see myself as that, but I can understand people seeing me as that. We were among the first guys who went into the clubs with no drummer or bass player. It was three guys behind keyboards. After Kraftwerk, it was the New Wave guys that did it. Now, one guy can go up there with a microphone and turntable behind them and entertain 20,000 people, and no-one will say anything.

During the early days, people would ask us “Hey, where’s the drummer?” We would say “He’s in this little box here.” It was a great period to be in. I saw a lot of technological innovation. Allan McCarthy, an early band member, even worked on his own MIDI-like system for Men Without Hats before MIDI came out. Allan and another guy who was a computer whiz, built the whole thing with a thousand feet of cable and it worked. Then, six months later, MIDI came out and made the whole thing obsolete. So, it was things like that. We did pioneer some things along the way, in the same way Kraftwerk pioneered them for us, and other bands pioneered things for them—and in the way we helped bands who came after us. And they’ll do it for the bands that come after them.

I’m just really, really happy people are still into the music. We were there at the beginning and that’s what it documents. I’m still amazed every time “Safety Dance” shows up in popular culture. Having it on Beavis and Butthead will remain my favorite usage, but every time it pops up somewhere, it’s great. It’s always a real source of enjoyment for me.