Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

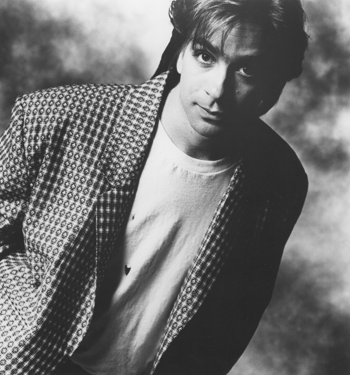

Scott Merritt

Hallucinations With Strings Attached

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1990 Anil Prasad.

Scott Merritt is an aberration in Canada’s music industry. After launching a nationally-acclaimed career, the singer-songwriter chose to continue living in his tiny hometown of Brantford, Ontario. In contrast, most of the country’s musicians that have found fame wind up in Montreal, Toronto or Vancouver.

It’s the resolve to remain within a small town vibe that permeates his latest album Violet and Black. But it doesn’t contain observations seen through rose-colored glasses. Rather, the disc often focuses on how the town’s factory-based culture and landscape are dramatically changing in the post-industrial world. But for the most part, specific locales and events go unmentioned. Merritt prefers listeners to integrate his lyrics into their own reality filters.

Merritt switched record labels from Duke Street to I.R.S. in the middle of Violet and Black’s release. What seemed like a good idea at the time proved to hinder the record’s visibility. Corporate politics kept the album from achieving its sales potential. They also conspired to prevent Merritt from releasing any new material for many years. During that time, he became an acclaimed producer. Artists he’s worked with include Ian Tamblyn, The Grievous Angels, Fred Eaglemith, Ruth Sutherland and Meg Lunny.

So what about his own music? Merritt has a large cache of songs ready to record, but he's not ready to resume his solo career yet. "There's no time frame right now," he told Innerviews in November 1995. "There's no-one holding an axe over my head anymore. The songs feel free even though they're not even released yet. It's a psychological exercise more than anything else. But a new album could happen in the next 10,000 years or it could happen tomorrow."

Your earlier work deals with surreal narratives and political viewpoints. I understand you wanted to avoid that territory on the new album.

For Violet and Black, one of the parameters I set for myself was to scrutinize what was really under my feet and not to get too removed or float up into the atmosphere or dream, like I had been known to do previously. But I think that scrutinizing what was under my feet is as full of hallucinations. The only difference is that the hallucinations have strings attached to the ground and that's really what I wanted.

Violet and Black reflects Brantford's small-town vibe. You've referred to it as "a town struggling in the post-industrial age." Elaborate on that.

There are a lot of factories that have closed down here. Yeah, it is a struggle. Life is probably a struggle in every town. The album is very particular to the idea that industry is moving out or closing down. I have a weak spot for the architecture of a dead factory—an old canal and a footbridge that used to be used by workers that goes across the canal that is now overgrown with vines and things. There's a feeling that it's an old world there and that it's just going to return to forest or fields someday.

It's hard to find a less pretentious moniker than post-industrial, but Brantford truly is post-industrial. In a lot of places, you'll walk out and there will be a train line that used to be used for shunting combines from some of the farm machinery places. The train line has turned to rust. It's just red rails and weeds growing up through them and it's maybe been only four or five years since it has been used. But it's returning to dust, in a way. So, the mind reels ahead a few years and the future is good. [laughs] I think what I'm talking about is if factories disappear, that can only help that scenario. But I certainly don't feel comfortable at all about the environment. Who does, really?

Let’s discuss some of the album’s lyrical themes, starting with "Burning Train."

It was meant to be more like snapshots taken from an area of town here that was, at the time, sort of a sore spot of the community. So, I'd walk around this place and write out little snapshots that I found as I went and try to assemble them in a flip-book narrative sort of thing. So, you take a snapshot, you take a few steps, take another snapshot, take another few steps, take another snapshot. And if you pile all these snapshots together and you flip them, then maybe there's a narrative or a through-line. Through-lines seem to be when you get this feeling of longing down there. I would describe the longing as being the burning train—the idea that you're on a train and you think you're going someplace until you realize that the train's on fire. The snapshots that I ended up keeping for this song tried to get across the idea that you work all summer trying to get the car to work so you can get out of the place and drive and just drive. You drive 20 miles after working all summer to get the thing going, and the engine locks. And that's the end of the trip—and you're back the next day.

What about "Wild Kingdom?"

"Wild Kingdom" is the closest I came to getting a surreal narrative on Violet and Black. [laughs] The idea of it is two people floating in the middle of the lake. One person is saying, "We'd better get back to shore." And the other person is saying "No, stay here. If it rains, it's going to flood and the waters will rise and we'll get closer to Heaven." That's the idea. It's about people—particularly people I get involved with—coming from different faiths.

"Are You Sending" was written about Brantford's recurring flood problem.

Theoretically, anyway. [laughs] I was raised being a fairly uptight Catholic in a necktie and a green suit with a little crest over the heart. Whenever it flooded, all the Catholic teachings and images sort of come back. I guess all I'm saying is that I have a soft spot for floods. We sort of had a pastime—a male bonding ritual. After a flood, you'd go down in the back of Bud's car, smoke cigarettes, and try to figure out whose picnic table that was or "Was that the Wilson's cat?" [laughs]

Are you still a religious person?

No. It's such a qualified thing. Religion is not the thing I go after. Napoleon said that religion is what keeps the poor from murdering the rich. [laughs] To that degree, I agree with him. Napoleon had a great amount of spirit perhaps, but he saw through religion. I try to climb that fence.

You dedicated Violet and Black's title track to Dianne Arbus.

Dianne Arbus is a photographer. She made photographs until about 1971—very moving photographs. They were often of outskirts and fringe subject matter, but handled with a great amount of care and love. She took a very wide variety of subjects—from freak show people, to transvestites at birthday parties on the 30th floor of some grotty hotel in New York, to nudist colonies, to some patriot watching a parade. But all these people have this weariness in them and she had this way of not condescending to them in her photographs. To me, that’s the real amazing key to her whole thing. These people were seen as beautiful things. She was out there doing that until it took its toll and she couldn't do it anymore. She committed suicide in '71.

The first inspiration to even considering writing a song about her was that I had this book of her collected works. We've had it here on the shelf for years. I keep going back to it all the time. It's a chronologically laid-out selection of some of her best-known photographs, compiled by her daughter. As you see the chronology of what she's done, it's a real story—a real novel. It's way beyond words. So, it was sort of big-headed of me to try to tackle it as a subject, but I felt driven to it—almost against my will. But I really felt that every time I looked at this book that some other people have got to learn about this person.

What inspired "Lockstep" from Gravity Is Mutual?

It was about that feeling right before you get involved with trying to change things. It’s the idea of not being able to face the idea of living a safe life. You can't settle for that. It was about somebody submitting to a parade of some kind and time is running out. There's all this "Tick, Tick" in it. I'm not sure now what I was paranoid about in those days. I think I was probably paranoid about bombs and the Love Canal, and things like that. I'm not paranoid so much about bombs anymore. I'm inspired that that whole mess is at the state it's in right now. The fact that whole mess has sort of been put on a back burner is a great first step. But, you know, as long as we don't see any development of this stuff going on in Iran and Iraq or someplace else, we can concentrate on what seems to be more important things, like trying to recover the ground and green grass and getting water that you can actually drink again.

You play sitar on the new album. What drew you to it?

Arthur Barrow [producer of Violet and Black] had one lying around his studio. It was real old. It was Robbie Krieger's. He had left it there. It was busted up and had about three strings left on it. One night, after we'd been in the cognac for a while, we decided to try and get it working again. And I just loved the sound of it. If I play other instruments, I usually end up playing them like I play a guitar or a drum. [laughs] It's either one or the other. When I was playing the sitar, I was playing it basically like I'd be playing a drum. I didn't really think of myself as Ravi Shankar at the time.

Contrast Arthur Barrow and Roma Baran’s production approach.

The best producers are sort of invisible. Arthur knew how to walk the line of when to bring his suggestion into the conversation or to the console. Roma was very invisible and her main role really was just trying to organize players and generate some sort of subtle spirit in the studio. Arthur would just sort of wait for the vibe to come, instead of trying to create a vibe. He sort of really left me up to my own creations, for the most part. He's a pretty manic guy. He’s a real media junkie. One second he would be sitting in front of the TV with a newspaper in his lap and totally sort of tuned in to some other wavelength outside of the room. The next second, he's making huge, grand gestures towards the stars about guitar chords and flat sevenths and stuff. [laughs] He's a real character.

Daniel Lanois helped produce your first record Desperate Cosmetics. What do you recall about the experience?

That was a long time ago. He engineered and sort of helped out with production, as was his wont all along. It was a great period of time. At the time, I took a lot of the creativity of those days for granted. In retrospect, after working with a lot of other people, you realize the difference. When you're 18 or 19 or whatever I was, you keep thinking there's other people out there like that but, really, he's a very rare sort of person. We all loved working at Grant Avenue. [Lanois’ studio in Hamilton, Ontario] It was like a magnet for songwriters in Ontario.

How did you end up working with Adrian Belew on Gravity Is Mutual?

About half-way through Gravity is Mutual, Roma thought that Adrian might be interested in helping us out. I'm not sure if she had sent him tapes or what, but she had talked to him and he was interested. So, we actually flew to Urbana, Illinois—where he was living at the time—and hooked up for a few days. He was extreme. My recollection is that the first three hours of the first session were basically spent with him trying to get his rig to work. What ended up being the problem after the third hour or so was his volume pedal was turned the wrong way around so that when he thought it was open, it was actually right off. So, there was three hours spent trying to find out which way his volume pedal should go. [laughs] But once we started working, we just did a ton of stuff. We let him do all sorts of tracks, then we went back to Canada and sort of pieced together the things we liked best out of what he'd done. So, it was fast. Extreme.

Matt Zimbel performs on the new album. That friendship goes way back.

We go way back. I had seen him play at a festival in Hamilton, Ontario. He was freelancing. It was before Manteca. He was playing timbales in a reggae workshop. I thought I should try to hook up with this guy somehow. I just invited him to do a couple of sessions, just to sort of try things out. He's very versatile. He's got a great spirit in the studio too. you can't hold him down. Nothing seems to lower his spirit in the studio. He's always enthused to try something out.

What does success mean to you?

Success is such a qualified thing. I think success is important. A certain amount of commercial success is necessary in order to survive and just do what you want to do. I've been lucky, but you can't take what few laurels you have for granted. The intention always has been to sort of explore writing, recording, and the creative part—to sort of go fishing in those swamps more. And, if I want to do that, I've got to feel that there's something coming back from some sort of demographic that belongs to record companies. You've got to feel that it's reaching enough people—that it warrants spending the amount of money you spend on making records. Otherwise, it's just another wasteful thing. You just become another bureaucracy that spends and doesn't earn its keep. I think when you talk about art, where the manufacturing of the art is reasonable in the costing, that's never wasted. I don't think the art gets wasted. But there's a great deal of wastefulness in its making sometimes. Does that seem like splitting a hair? I don't think it is.

You're never past the point of caring about the project but, when it comes to marketing, you've just got to say "Yeah, it really is out of my hands to a large degree." You can only make your suggestions to the people that wield the money. The thing is, it's not the reason why we make music. And that's the thing you've got to keep reminding yourself about whenever these things come up. You know, lawyers and things aren't the reason why I make music. So, to survive, what I do is just lock the door and start writing again and get lost in the things that you love to get lost in.

How have you responded to labels that attempt to tamper with your music?

Whenever my artistic freedom was threatened—and of course, it has been threatened because that happens all the time—I get completely unreasonable with people. [laughs] I hate to use it as a crutch or something. Some people, it seems, they sort of can hide behind the idea. A lot of times, I see artists during interviews saying "I made the record I wanted and nobody told us what to do." Sometimes, if a record is not that accessible, then people can hide behind it and call it art and say that it's just not understood or something. But I think the object of the game is to be understood. If you really have conviction somewhere that you can be understood, then you don't need people to tell you how to go about doing that. That's a big qualification to all that other stuff we just talked about. In the end, artistic freedom is something to fight for, if you really feel that you're fighting for a platform to be understood by.