Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Porcupine Tree

Dream Logic

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2010 Anil Prasad.

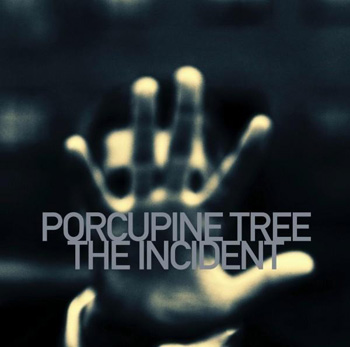

If listeners aren’t careful, the latest Porcupine Tree album might blow their speakers or earbuds apart seconds after hitting the play button. The British prog-rock outfit’s tenth studio release The Incident kicks off with a window-rattling, repeating power chord designed to focus its audience on the album’s epic conceptual themes.

The disc explores human tragedies that are often trivialized by being reduced to the word “incident” by the media. The album’s dark subject matter involves delving into a terrible traffic accident and its aftermath; religious cult activity; and the impacts and emotions that occur when bodies are found at random by strangers. It’s not all doom and gloom though. The album also looks at positive personal incidents from the life of frontman, guitarist and multi-instrumentalist Steven Wilson, including his first love, a lost friendship, and the day he chose to throw caution to the wind and become a full-time musician.

The album paints its sonic pictures with varied brushstrokes. Together, Wilson, keyboardist Richard Barbieri, bassist Colin Edwin, and drummer Gavin Harrison, combine their genre’s proclivity for extended, mercurial passages and intricate interplay, with metal, pop, electronica, and folk influences. The album covers a variety of moods from dark and thunderous to dreamy and delicate. It’s an appealingly eclectic approach, and one that’s captured the attention of an exponentially-growing fan base. In fact, word-of-mouth recommendations and grassroots marketing efforts propelled The Incident to a simultaneous debut in the Top 20 in both America and Britain.

The band also just released Anesthetize, a live DVD capturing its 2008 Fear of a Blank Planet tour. In addition, a download-only live recording from the same tour titled Atlanta is now available, with the band’s proceeds going to the Mick Karn Appeal, supporting the ex-Japan bassist’s battle against cancer.

Outside of Porcupine Tree, No-Man, Wilson's atmospheric pop duo with singer-songwriter Tim Bowness, recently put out Mixtaped, a performance and documentary DVD. Another documentary DVD titled Insurgentes, based on Wilson's 2009 debut solo album of the same name, is due out in the fall. His ambient, drone-based work under the Bass Communion moniker also continues, with its latest live recording Chiaroscuro. And The Complete I.E.M., a box set of the entire output of Incredible Expanding Mindfuck, Wilson’s Krautrock-influenced experimental project, was just released. Wilson has also remixed the majority of the King Crimson back catalog in surround sound, which is being reissued throughout 2010 and 2011.

Wilson explored many facets of his diverse output in this wide-ranging conversation with Innerviews.

The Incident features a very provocative, in-your-face opening sequence. What made that appealing to you?

There’s a tradition with Porcupine Tree in which we start albums with a little sound effect or texture that eases you into the musical journey. This time, I thought “Wouldn’t it be great to start with a real statement of intent?” The American composer John Adams is a big influence on me. He has a piece titled “Harmonielehre” that starts with the whole orchestra playing these big grand power chords stabbing away. It’s an almost primitive approach, reducing music down to one big note. I thought “If we’re going to write a big, album-length piece of music, let’s not start with any pretentious ambient stuff. Let’s go for the big note too.” So, I sat down and came up with this power chord that appears in three groups of three. It sounded good and the rest of the album grew from there. That represented a key difference in the creative process compared to previous Porcupine Tree albums. With this one, each piece I wrote naturally led to each subsequent piece. So, everything grew out of that opening salvo. The order you hear the album in is literally the order it was written in. With the other albums, I wrote a bunch of parts and found the best way to structure and sequence them.

The plot and character development, structure, and story evolution of The Incident meant I had to write in a linear way. It was like writing a movie script. I don’t necessarily mean lyrically. Lyrically, this album is much less conceptual than Fear of a Blank Planet. It has a much looser concept. But musically, it’s all about the structure, the story and how it unfolds, and the way the characters come in and out of it. By characters, I mean the different musical themes and chord sequences that reoccur, and how the rhythmic opening to “Occam’s Razor” appears again later. That’s a lot like character or plot development. So, I think the script analogy works really well. I love cinema as much as I love music. I often think very much in terms of cinema when it comes to music.

Did you map out any of the elements before starting to write?

Not consciously. When I start writing, I’m always thinking “I don’t know where the story is going to go.” I know some writers map out the whole plot, but it’s not my approach. For this album, I wrote chapter one, which suggested chapter two, which suggested chapter three. It’s a very intuitive process and it’s something I could never have done before now. It took a lot of experience and learning from my mistakes to accomplish it. The Incident isn’t he first time I’ve tried to do this. I tried to do it as far back as The Sky Moves Sideways. The original idea for that album was that it was going to be a one-track record. I got really bogged down in the idea and it didn’t work. It felt too ponderous and long. I ended up scrapping the ideas and wrote some short pieces instead. That’s how the album evolved into what it became.

The Incident is the latest in a long line of attempts to write a long-form musical novel, having focused on short stories before. For whatever reason, perhaps because of experience, it seemed to work this time. I love big, epic, ambitious novels and movies, especially those that don’t necessarily move in a logical way using a typical Hollywood approach. I prefer the European approach, which is often quite fragmented and surreal, which enables things to evolve in a unique way. It’s almost like dream logic in that you don’t necessarily arrive at the end you intended. Instead, you arrive somewhere you had no idea you would end up.

It’s amazing to witness The Incident attain serious chart positions and sales, given the fan base remains so organic.

Totally. It’s still all word-of-mouth. What a great position to be in. It’s fantastic. It’s funny, the more willfully uncommercial we are, the more successful we are. Fear of a Blank Planet was our previously most successful record and The Incident has sold more copies than that. So, the more pretentious and ambitious we are, the more people that like Porcupine Tree. Perhaps it’s a sign of the times. Maybe download culture has driven people back to looking for something more substantial—something that can justify them buying a physical product.

In the past, we’ve tried to be a little more what the record company wanted. We would give the record company a couple of singles. With Fear of a Blank Planet, we said “Fuck it. We can’t write this stuff. We’re not good at it.” There are a few songs in the back catalog that are quite good pop songs, but I recognize that’s not what we do best. We do the long-form things the best. The Incident is a continuation of the Fear of a Blank Planet philosophy and we’re doing better than ever.

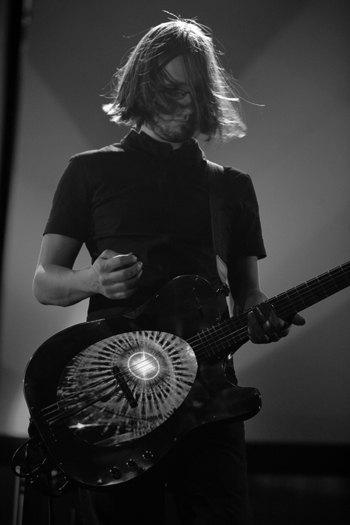

You’re uncomfortable with your emerging guitar hero status. Why?

I feel like a fake because I’m not a great guitarist. I know I have a sound that’s my own, but it comes from my overall vision for how I want to make records and my production approach. I recognize and accept that I have a style too, and I think it partly comes from my limitations. I’m just not interested in playing fast or being an Olympic guitarist. That doesn’t appeal to me. I’d rather hear someone play one note with feeling that can break my heart, than 50 notes that mean nothing. I’ve never been interested in being a great technician, which is just as well. I don’t have the discipline or inclination to do that.

How do your limitations on the instrument influence your creative process?

I write in a very intuitive, idiot savant kind of way. Once I’ve put the music together, I have to present it to the band at some point. For instance, Richard Barbieri might say to me “What’s the chord?” I’ll say “I don’t know, but this is how I do it” and play it for him. He’ll say “That’s a B flat diminished ninth,” and I’ll respond “Whatever.” [laughs] When I write, I’m literally looking for sounds that feel good. I don’t have any academic background to know what a B flat diminished ninth is. I think this holds true for most of the important musicians I really love too. I don’t think Bob Dylan knew a lot of the time what chord he was playing. In contrast, all of the kids that go to the Berklee School of Music usually graduate and tend to start making jazz-fusion music that no-one listens to except other music students. I believe you can sometimes know too much about what you do, and the truth is, I’ve never read guitar magazines or fetishized the tools I use to make music.

Elaborate on that for me.

I don’t approach the guitar the way a typical guitarist or musical purist would. I’ve always approached it as part of the texture of the songs. So, I use a lot of amp simulation software in my work. When I tell this to some other guitar players, they’re horrified. It’s a common thing to do, but most real guitarists still feel you should put a guitar through a real amp and mic it up. And those who use amp simulation are often trying to emulate classic amp tones. This has led to a lot less distinctive musicians. It’s so easy to copy the tones of other musicians. In the '70s, there was no such thing as a $250 box with presets that let you sound like Jeff Beck or Eric Clapton. What I do is use amp simulations in a purely creative way, and that’s why a lot of people think some guitar sounds on the record are keyboard sounds and vice-versa.

Tell me about your amp simulation software setup.

I take my guitar, plug it directly into an Apogee Trak 2 Mic Preamp and A-D Converter and go straight into an input bus, and from there into a Logic front-end, running the Pro Tools engine underneath it. Then I put it through a Line 6 Amp Farm, and then into a chain of ridiculous plug-ins that I experiment with until I get sounds and textures I love. I use a lot of plug-ins that aren’t meant for guitar at all. I use a suite of plug-ins called D-Fi for Pro Tools. They’re designed to fuck up songs. I particularly like the ring modulator plug-in. It’s very low-fi and allows you to reduce the bit rate and sample rate of a sound until it begins to break up. You could never get such digitally distorted sounds out of a real amp. I also love the Line 6 EchoFarm which lets me add wobble and dropouts to the sound. In addition, I use the Focusrite d2/d3 multi-band EQ and compressor/limiter plug-in bundle. I use a lot of extreme d2-based EQ in my stuff.

I also love a lot of low-fi stuff. I like to even add vinyl crackle and old, primitive analog sounds into my work. There’s a track called “The Yellow Windows of the Evening Train” that doesn’t have any guitar on it. But all of the sounds on it are processed to sound old. That usually means taking a load of bottom end and top end out. The reason people say vinyl sounds warmer is because CDs reproduce the top end so much better and more clearly. So, the old kind of sound was much more warm and middle-y. One of the great ironies of the way I make albums is that I record completely digitally, yet people say my records sound like vintage ‘70s records. The reason is that I take a lot of that top end out to make the music sound more golden nostalgic and old. The same goes for guitar tones too. I like them to sound old. And the only way I know how to do that, ironically, is through digital recording technology.

On the current Porcupine Tree tour, you mainly rely on Paul Reed Smith Custom 22 guitars. What makes them ideal for you?

They feel great and look great. They are also incredibly versatile and can cover a lot of bases that more classic guitars can’t. When you listen to Porcupine Tree music, you’ll hear a very wide sonic spectrum, from extreme metal lines to tones that include the ambient, blues, jazz and acoustic worlds. When we recorded The Incident, I used Les Pauls, Stratocasters and Telecasters, and the Custom 22 allows me to replicate their sounds within a single instrument.

You also used a custom Paul Reed Smith baritone guitar on the new album. Describe it for me.

Winn Krozack, the Director of Artist Relations at Paul Reed Smith, offered to make me a guitar. I said “One thing I’ve always wanted is a baritone because there’s a Swedish band called Meshuggah, and I love how they play their guitars tuned way down, with the top strings taped up.” It’s a beautiful instrument with a faded blue mateo top and a satin nitro finish, 27-inch scale, 22 frets, and a tremolo bridge. I also asked them to do something unusual and put a piezo pickup on it as well, so I can combine the glitchy sound of the strings with the Paul Reed Smith Mark Tremonti treble pick-up that’s on it. You can hear the combination on a track on The Incident called “Your Unpleasant Family” that has a very jangly, open guitar chord sound, but it’s played on the baritone, so it’s much lower than a typical guitar register. In general, this particular guitar informs a lot of the heavier stuff on the album.

Typically, you use standard tuning, with the exception of dropping your bottom string to D or C. Why is that your preference?

It came from me listening to metal music. A lot of those guys go down low. Porcupine Tree doesn’t play metal music, but I like some of these tones. However, I don’t like a lot of heavy records, in general. I find it quite difficult to listen to them for more than 10 minutes. Texturally, they get very same-y. It’s as if someone is screaming in your face for 60 minutes. [laughs] You become kind of immune to it after a few minutes. With Porcupine Tree, when we do use heavy sections, it’s the context that makes them have a significant impact. For instance, “Circle of Manias” is a very heavy piece, with the baritone guitar tuned way down. It comes immediately after an acoustic ballad. I think that sense of relief and dynamics emerged for me from loving the sound of extreme metal records, but not loving the records themselves that much.

The AlumiSonic Ultra 1100 guitar is another core instrument in your arsenal. What do you like about it?

It looks fantastic because it’s entirely made of metal, and it sings in a way no other guitar I’ve ever had does. The sustain is really impressive too. It generates beautiful, sympathetic feedback between the amp and guitar that I’ve never experienced before. Because it’s made of metal, it has more reflective surfaces, so the harmonics reflect more freely and musically.

Describe the other elements of your signal path.

I don’t use a lot, typically. In concert, 60 to 70 percent of the time, it’s just my guitar going through my Bad Cat BC-50 amp head into a matching Bad Cat 4x12 cabinet, maybe with some delay and reverb. I have a TC Electronic G-System effects processor that’s easy to use, but in terms of actual sounds, they’re the same as you get out of any typical guitar box. I’m also using the Option 5 Destination Rotation Single Vibe pedal, Boss FV-500L Stereo Volume pedal, Soundblox Multiwave Guitar Distortion pedal, Boss SD-2 Dual Overdrive pedal, and a Jim Dunlop Cry Baby Wah pedal.

The new album has some intriguing and entertaining guitar solos. What can you tell me about your soloing philosophy?

It’s based on the Robert Fripp approach—play the notes with conviction, but don’t think too hard about what you’re playing. Also, play as few notes as possible with as much emotion as possible. I can’t play any other way. [laughs] I can’t play fast. Gavin Harrison found a clip on YouTube of a guy who can play “Flight of the Bumblebee” on guitar at 320 BPM. He must have spent months and months learning how to do it. Why? Unfortunately, a lot of kids are enthralled by the athletic element, resulting in a lot of so-called shredders out there. It’s like if we conducted this whole conversation with me speaking at an incredibly fast rate constantly, without putting any expression or feeling into my voice. You would learn nothing about me. It’s the way I express the words and the feeling I put into them that tells you something about who I am.

I understand you were unhappy being forced to learn guitar as a child. Give me a snapshot of that period and how your enthusiasm for the instrument reemerged.

It’s quite simple. My enthusiasm reemerged when I fell in love with music. Before that, I wasn’t interested in music. I was interested in soccer. My parents tried to send me to piano and guitar lessons at age seven, when I was more interested in being a soccer player. By age 10, I discovered pop and rock music and fell in love. I didn’t fall in love with the idea of being a musician and touring, or becoming a star. I fell in love with one thing, and one thing only, which is the idea of making records.

My goal was to hold something I made in my hands, which in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s meant vinyl. It’s that straightforward. From then on, I did whatever I needed to achieve that. I retrieved this guitar that had been abandoned a couple of years earlier in my parents' attic. It was from Woolworth’s and it cost 25 quid, which was a lot of money in those days living in Hemel Hempstead, a city north of London where I still reside. I tuned all the strings on the guitar so it made a nice sound and I started to learn how to play guitar. I also started writing my own songs from day one. To this day, I cannot play anyone else’s music. For instance, if you asked me to play “Stairway to Heaven” on guitar, I would have no idea.

Your Cover Version series of releases provide evidence to the contrary.

[laughs] Okay, yes, I can learn those things when I need to, but I don’t learn things just for the sake of doing so. If you say to a lot of guitar players “Play me the first lick of Black Sabbath’s ‘Snowblind’ or Fleetwood Mac’s ‘Landslide,’” they can do it. It’s almost part of their vocabulary to know these things. But I don’t know anyone else’s music at all except mine beyond the cover versions I’ve recorded.

Your general musical influences are very well known, but I’ve never heard you talk about your key guitar influences before.

Fripp is my number one influence, no question. The others are mainly the major prog-rock guitarists, including Alex Lifeson and David Gilmour. I’ve been working a lot with Fripp recently, remixing the King Crimson back catalog. When I was very young and first heard those King Crimson records, I would think “That’s just wrong. You’re playing the guitar wrong, mate!” But the more you start to listen to Fripp’s playing, the more you appreciate his choices of notes. Fripp is a very unique man and his guitar playing reflects that. He doesn’t pick notes in any sort of logical way, but he plays them with conviction. He blew my mind open when I heard his solos on King Crimson’s “A Sailor’s Tail” and Brian Eno’s “Baby’s on Fire.” Just extraordinary stuff. I’ll never be able to play like that because you have to have the mind of Fripp to do that, but there is certainly an influence from him in terms of choosing unique notes and making them sound beautiful.

Are you quoting from King Crimson’s “Red” on “Occam’s Razor?”

Probably. [laughs] I’m sure I am. It’s in my DNA. It doesn’t matter if it’s conscious or unconscious. I can’t get away from it and I don’t want to get away from it.

What was it like for you to work on the King Crimson surround remixes?

It was an amazing experience. It’s funny, because one of the things someone asked me when I said I was going to work on the King Crimson catalog was “Aren’t you worried it’s going to destroy your love of this music?” That’s because there’s a sense of if you know too much about the way things were put together, it can rob you of some of the mystery and enigma. I would say the opposite situation occurred. I now have even more respect and appreciation for the work, and particularly for Robert. There are some extraordinary ideas going on in those records. Being able to go inside them and decode how they were put together was fantastic. Truthfully, I still don’t understand how Robert put everything together. He was no help in explaining things to me. [laughs] He’s not about to help you understand how the music was created. In a way, and I mean this positively, he probably doesn’t know himself.

What artistic license did Fripp provide you during the remixing process?

What would happen is I would get the tapes, transfer them, and create the mix. Then Robert would come along and we’d listen to my mix. He’d make suggestions and changes. He made some changes I would never have been brave enough to make because I was trying to be faithful to the original. But Robert would say “Oh no, I never liked that. Let’s get rid of that.” [laughs] It’s stuff that people are intimately familiar with. They’ll probably be horrified by some of the changes, but the thing is, it was Robert’s decision. He always said to me “You have the fan’s perspective. If you think it’s the wrong thing to do, I will bow to you.” But sometimes he’d make a suggestion and I’d say “Yeah, I actually kind of agree with that. Even though I’m intimately familiar with the original, I can understand why you want to do it.”

We made a big edit to the improv section of “Moonchild” from In The Court of the Crimson King, which I always felt went on too long. Most people do. Robert said “Let’s cut it.” I said “Are you sure? People have been listening to this record for 40 years.” And Robert said “Yeah, fuck it. Let’s cut it.” [laughs] So, “Moonchild” is three minutes shorter on the master. But you get the full-length version as a bonus track.

Ultimately, I was trying to be very faithful to the original albums, because I’m intimately familiar with them and love them. I think a lot of people will understand why Robert has done what he’s done. The only things I would agree with him on are when there was a sound reason to make a change. For instance, he took out some synth overdubs that Pete Sinfield had made to Lizard. What you have to understand is when you’re in a band, there are a lot of politics and compromises going on. Now, 40 years later, he doesn’t have to bow down to them. He doesn’t have to keep people happy. So now, he’s like “I never liked that. We only did that because Pete wanted to do some synth stuff.” So, he took stuff out and I totally agreed.

Bass Communion remains an important part of your solo output. Describe the vision that informs your output under that name.

The approach I’ve adopted with Bass Communion is that every record uses a different musical force. So, Ghosts on Magnetic Tape is mainly piano and old 78 RPM records. Pacific Codex was based purely on gongs and metal sculptures. And Molotov and Haze, the last studio release, was an album based entirely on guitar. And for the next album, I’m sure I’ll use a completely different force as well. The idea is to use different ingredients each time and figure out how to Bass Communion-ize them. I think the problem with a lot of drone artists is that the records sound kind of the same after awhile. With Bass Communion, every record is kind of different. Everything has been through the Bass Communion process, but the source material in each case is unique.

What can you tell me about how you used and processed guitar for Molotov and Haze, and the live album Chiaroscuro?

It’s all laptop and guitar. [laughs] The laptop is running Logic, running a lot of plug-ins. Basically, what I do is string about 15 plug-ins on a channel strip, set up basic settings on them, and dial them in and out. I’m also using a Line 6 DL4 Stompbox Delay Modeler to create loops. So, I’m feeding in notes from the guitars into the Line 6, which creates the loops, and that feeds into Logic. I’m really just playing very subtly with the mutating textures of the guitar loops. The plug-ins are native to Logic. They’re the ones that come with it for free. Some of my favorites include “Spectral Gates” which is like a noise gate, but it only affects certain parts of the frequency spectrum. I use it a lot. There’s also a whole range of very bizarre distortion plug-ins that affect the harmonics of sound in very eccentric, unique ways.

Describe your attraction to the universe of drone-based music.

I find it very interesting because it’s very hard to convince many music lovers that drone music is music at all. Most Porcupine Tree fans would probably have a hard time accepting Bass Communion as music. The problem is, if you take away rhythm and harmony from music, most people will not recognize the existence of music at all.

I think that holds true for the West, but not necessarily for many Eastern cultures in which drone-based music is a part of everyday life.

That’s exactly true. For me, drone music goes to the very root of what we are. The album I fell in love with as a kid was Tangerine Dream’s Zeit. I consider it the original ambient record. It changes the way you think about the space you’re in when you listen to it. A way of explaining to people what drone music is, is saying it’s like filling a room with incense or perfume. But let’s get away from the drone thing for a minute and talk about it as purely textural music. Anyone that’s been to a movie theater and seen a horror movie or thriller has probably responded to sound as pure texture in an emotional way. In a horror movie like The Shining, you’ll find drone music that’s scary as fuck. However, if you play that music in a standalone context and say “This is music” you’ll find that people say “That’s not music. That’s just sound.” But if you had an emotional reaction to it in a movie, why can’t you have an emotional response when it’s reduced to pure textures? It’s just a question I ask. It sounds very pompous, but I’m saying it anyway. I want to educate people to listen to music in a slightly different way or perspective.

I was initially into later Tangerine Dream and then I heard their Zeit album. The first time I heard it, I said “This isn’t music. This is just people mucking about.” The more I listened to it, the more I began to decode what was so special about it. Now, if you ask me what my favorite album of all time is, very often I’ll say Zeit. The record never loses its appeal for me. It’s the greatest ambient record ever made. It has a complete sense of otherness that I cannot explain. It’s a bit like Fripp’s guitar playing. It keeps its enigma. Since I got into Zeit, that kind of pure textural music has been my music of choice to listen to for pleasure. I don’t find it obtrusive or bland. It’s neither one nor the other. It has an incredibly emotional effect on me, but I’m always able to do other things while it’s happening around me. That’s where this analogy with incense and perfume really comes through.

Speaking of film, what’s going on with your Deadwing script?

We keep showing it to anyone that will read it, but it’s very hard to get someone to give you a million dollars to make a movie, particularly one that’s very uncommercial and written by people who have never written a script before. That’s why I took the pragmatic step of making a film about the making of my first solo record Insurgentes. Lasse Holle came out with me and we made this surreal road movie that’s much more than a documentary. It has a lot weird, surreal, fucked-up stuff in it. In addition to stuff about the album, it deals with my thoughts about download culture. You’ll see me destroying 10 iPods in 10 different ways. It has Trevor Horn talking about the same subject. There’s also a social commentary aspect about what it’s like to be a musician in the current era. We’re very happy with it and I’ve got my fingers crossed that it will get some attention. It’s a beautiful piece of filmmaking. In the back of my mind, I hope that if it can get some kind of profile, it will give us more of a chance for Deadwing. So, my aspirations for the film world are not over yet.

Give me a snapshot of the coming months for you.

After this period of wall-to-wall Porcupine Tree touring, I’m going to start working on my second solo album. I was very pleased with the first one. It was well received, which was gratifying, because it was quite different. It had aspects of my other projects, but fused together in a way I had never pursued before. It combined some of the Bass Communion aesthetics of noise and texture with songwriting, using an orchestra in an atonal, wall-of-sound way, and integrating my love of shoe gazing music for the first time as well. No disrespect to Richard Barbieri intended, but it was interesting to be in a position in which I didn’t have to rely on a keyboard player. So, I used the guitar in a more textural way. Now, I'm looking forward to the next step.

I have no idea how the album will sound. I’m going to take what I did on Insurgentes and go further into more twisted and experimental areas, but still have it all based on what are effectively songs and vocal pieces. I’m just going to go to my studio and start experimenting, which is how the first album happened. It’s quite liberating not to have to consider what other musicians are thinking about. When I write for Porcupine Tree, I’m aware that I’m writing for three other musicians and I’m cognizant of what they do and do not like and what they will and will not respond to in a positive way. So, while that limitation is essential and important for a band that has a style and direction, at the same time, I’m happy not to have that limitation with my solo material. So, if I want to fuse a beautiful orchestral passage with a complete wall of noise within a pop song with trip-hop elements, all in the space of eight minutes, I can. And that’s what I did with Insurgentes. So that will be my next major writing and production project.