Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Trevor Rabin

Capturing Adrenaline

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2004 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Varèse Sarabande

Photo: Varèse Sarabande

Trevor Rabin's music has made a dramatic impact on the world. He’s an A-list film composer that’s helmed the scores for blockbusters including Armageddon, Con Air, Gone in 60 Seconds and Deep Blue Sea. He was also the driving force behind progressive rock goliaths Yes during the ‘80s and early ‘90s—the revitalized line-up behind 1983’s multi-platinum 90125 and the number one single “Owner of a Lonely Heart.” Rabin served as the muse behind the group’s rebirth, as well as its formidable lead guitarist. Prior to Yes, he headed up Rabbitt, the biggest South African rock outfit in history. In addition to hit albums and singles during the mid-to-late ‘70s, Rabbitt was known for its anti-apartheid stance—a rarity for celebrities during that era.

Now based near Hollywood, CA, Rabin recently released five CDs on the Voiceprint label that spotlight his lesser known work. The first three are reissues of his long out-of-print early, singer-songwriter efforts: 1978’s Beginnings, 1979’s Face to Face and 1981’s Wolf. As historical documents, Beginnings and Face to Face provide a glimpse into an ambitious young artist determined to put his vision into motion. While the albums are straight-ahead late ‘70s rock efforts, they are notable for the fact that Rabin plays most of the instruments and handles the bulk of the production. In contrast, Wolf was significantly more satisfying, with engaging songwriting and powerful arrangements that straddled the melodic and anthemic. Wolf also featured an all-star cast of contributors, including Jack Bruce, Ray Davies and Manfred Mann.

The other two Voiceprint releases, 90124 and Live in L.A. are previously unreleased collections. 90124, a play on 90125, an album that derived its name from its catalog number, focuses on demos of tracks that emerged throughout Rabin’s tenure with Yes. Five of its tracks pre-date 90125 and show how fully formed his songs were prior to his involvement with the band. Live in L.A. was recorded during Rabin’s 1989 tour in support of his then current solo album Can’t Look Away. The disc offers raucous renditions of key solo and Yes tracks, performed for a wildly enthusiastic audience.

In this revealing conversation, Rabin discusses his varied and accomplished career as a solo artist and film composer. He also goes into detail on his years with Yes, including his departure from the group shortly after the release of 1994’s Talk, one of the most adventurous and underrated albums in the group’s catalog.

Photo: Varèse Sarabande

Photo: Varèse Sarabande

Outside of your soundtrack work, you’ve kept a low profile. What motivated you to get back into the spotlight with the recent releases and reissues?

It was actually not my idea. I had a desire to release the Live in L.A. tapes because I was quite fond of them. I mixed them a long time ago and thought they sounded quite good and thought at some point I wouldn’t mind putting them out. I mentioned this to Alex Scott [Rabin’s manager] and he had been in touch with Voiceprint and Robin Ayling [the label’s president] was quite keen. That’s where it really started. When the time came for me to meet Robin, he came over to the studio and one thing led to another. Discussions about the first three albums came up. 90124 was really Rob’s idea. He was in the studio looking through my tape library and saw rows and rows of demos and masters. He’d ask “What is this? What is that?” I’d say “These are the demos for 90125 and here are the demos for Big Generator.” Then he asked if they were demos with the band. I said “Oh no, these are demos I did by myself. And on the 90125 stuff, they are demos from before I even met the band.” He got quite excited. [laughs] We then talked about putting them out and that’s when Rob came up with the idea of calling it 90124.

Did the 90124 album represent an opportunity to clearly define what your role in 90125 was?

From Rob’s point of view, that was where he was coming from. From my point of view, it doesn’t define what my role was. It would have had I stopped there and given the songs to the band, but once we started, I was very hard at work recording and changing them. I think it would be a little clearer if I played you a demo from a solo album to see where that started and where I landed on my own. I always felt the demos for 90125 and Big Generator are embryonic versions of what I did afterwards. My input didn’t stop from a development point of view with those demos, but they do provide a good, clear idea of where the process began.

How do you feel 90124 hangs together as a listening experience?

I think it’s quite interesting. Rob was very excited about doing it. I was a little apprehensive at first. I’m certainly much more positive about it now that it’s finished. I was apprehensive about the idea of putting out something that’s so brutally honest and real, because when you’re doing stuff like that, there’s no concern about making a fool out of yourself. That’s what I allow myself to do when I’m writing something. I don’t care if it’s good or bad. But if I was going somewhere and thought “Man, this sounds like the worst kind of corporate rock I’ve ever heard” and knew other people would hear it, I’d stop right there. When you write, you have to be as free as possible. So, I don’t care during the initial stages how bad it goes. The important thing is what decision is made once stuff is written and determining if something is really bad and not wanting anyone to hear it. That’s where it was very difficult to put this together. There was clearly a lot of stuff that I would never in a million years put out out as a master. I hope it is very much understood that 90124 represents a brutally honest first draft.

Yes recorded an epic, unreleased track titled “Time” during the original Cinema sessions. What can you tell me about it?

I haven’t seen or heard that track for so long. I think Alan White and Tony Kaye have versions of it. It was leading up to the point where it was going to be a track on one side of an album—that was when we were still making vinyl albums. [laughs] It was a strong possibility had we kept going with it. It probably would have landed at longer than 20 minutes. I don’t mean to skip too forward here, but when Talk was discussed, Phil Carson [President of Victory Records] said to me “I really want you guys to do a long-form Yes song.” My issue was what does that really mean? It sounds like a very contrived attempt to do something. Something like that just needs to happen. The only contrived thing about it should be I’m allowing myself to do something without any time constraints. That’s what happened with “Endless Dream.” But as far as saying “Okay, I’m going to create something that’s really long”—that’s just contrived.

“Time” was really something that just happened. It was four guys rehearsing every day and it was sounding really good. We were real happy with where it was going and it just kept building and building. There wasn’t a specific attempt to write something that was very long. I understand the idea of that attraction and it’s something that’s attached stylistically to Yes in a big way, but I think even things like Topographic Oceans didn’t start initially as “We’ve got to do something really long.” That’s not going to help any flow. Things have to happen naturally.

Originally, Trevor Horn was going to be the lead vocalist for 90125. Give me some insight into that period.

Yeah, that’s true. It was Chris’ [Squire] idea. I think Trevor did a magnificent job on Drama. His intelligence of being able to come in and do that record was extraordinary.

Why didn’t having Horn on vocals work out?

I think it did work out. It was an evolving situation that started with him playing one role and landing up in the real role he should have been in for that incarnation. It’s quite funny. Trevor and I met at that time. Initially, it was just me, Chris and Alan. During the first rehearsal, there were five of us, including Trevor and Tony. Trevor put on a guitar and I was a little big indignant, thinking “Well, what do we need that for?” And even from a vocal standpoint, I was a little confused. For the first couple of rehearsals, Trevor and I didn’t get on. In fact, at the beginning of 90125, we had some real issues. I wasn’t that keen and I think he looked upon me as being stubborn. It’s ironic that Trevor and I have turned out to be very close friends. It’s a real credit to him that he went from being someone questioning what he does during the early stages of 90125 to becoming one of the greatest producers of all time.

Yes, 1984: Alan White, Trevor Rabin, Jon Anderson, Tony Kaye, and Chris Squire | Photo: Atco Records

Yes, 1984: Alan White, Trevor Rabin, Jon Anderson, Tony Kaye, and Chris Squire | Photo: Atco Records

Horn received writing credits on 90125 for “Owner of a Lonely Heart” and “Leave It.” Tell me about his input.

For “Owner,” he was helpful on certain lyrical things. The one thing credits don’t reveal is the proportion of input of people. They just list the names. He had a great staying power for “Owner.” It was always about that song for him. He said “Once we have that song right, we have the flagship for the album.” It was a really difficult song to record and get done. I always knew it was going to be, but Trevor stayed the course and was resilient.

During the 90125 sessions, Kaye left and was briefly replaced by Eddie Jobson. Kaye then rejoined. What happened?

Tony and Trevor just didn’t hit it off and it got to the point where it really wasn’t working at all. Next thing I knew, Tony was about to leave and Trevor called me and said “We’ve done some of the keyboards on the album and I don’t have a rapport with Tony. You’ve obviously done the keyboard stuff on the demos. How would you feel about playing keyboards as well?” I was concerned for Tony, but once I realized that it was a bad situation, I thought “Well, we have to get this done.” There was no intention at that point for Tony to leave the band, but rather to continue in a slightly different way. So, I started working on keyboards and Tony was gone for awhile. He went back to L.A. and then we started thinking maybe the best thing to do is find someone who will play the role in a different way. We spoke to some people and Eddie was one of them. Actually, Eddie was never really in the band. Eddie came along during the time we were doing the video for “Owner of a Lonely Heart,” so he came along to that shoot. Having him in the band was still a question mark and there were some unresolved issues. So, very soon thereafter, we decided we were going back to Tony to try to repair what damage might have been done. We did and everything was fine from then onwards.

Squire once mentioned Jobson did himself no favors by wearing heavy make-up during the “Owner” video shoot.

[laughs] I didn’t know he said that. That’s quite funny. It’s typical Chris. I think the bigger issue was how long it took for the make-up to be put on. I think he was in there for a long time doing his make-up. I think Chris is being humorous when he said that.

Why did the band initially go with Kaye, given his reported reluctance to use synthesizers?

I don’t think that’s quite accurate, because Tony is a very collaborative kind of guy. Tony was Chris’ idea. People don’t seem to understand this, but when required, Tony has quite a facility and a reasonable amount of dexterity. It’s not like he can’t do that stuff. He was just the guy Chris thought would fit in with what we were doing and what I do.

Yes, live 1988: Trevor Rabin and Chris Squire | Photo: Atco Records

Yes, live 1988: Trevor Rabin and Chris Squire | Photo: Atco Records

Is it true the band was using an offstage keyboardist during the 90125 and Big Generator tours?

What happened is there were so many things to do from a point of view of overdubs and enhancing vocal harmonies with vocoders. Tony’s roadie could play, so we thought, why don’t we get him to do those things under the stage if they’re needed? But it wasn’t like we had another keyboard player. What the guy under there was doing was minimal.

Let’s go through your solo albums and have you provide any thoughts that immediately come to mind. Let’s start with Beginnings from 1978.

Beginnings was the first album after my time with Rabbitt, which musically speaking, was one of the most exhilarating times of my life. It was a strange period. It was the first time I had been on my own. I had always been in a band from an early age and worked in a collaborative way. The guys in Rabbitt are still extremely close friends of mine. So, it was a lonely time. When there were issues that couldn’t be resolved musically, it was me that had to resolve them without any kind of real dialog with someone who cared as much as I did.

I haven’t heard Beginnings for so long. I think there are moments on there that were naïve and moments that are quite inspired. It’s a mish-mash of both. I was still living in South Africa and working towards moving out of the country to England. So, it was kind of a peculiar time. I listen back fondly to some of it. Some of it I cringe at, but I’m glad I went through with it.

Next up is 1979’s Face to Face.

That was definitely a confusing period because I had now moved to England and was trying to write the second album. I think Face to Face suffered from some of the issues we talked about in terms of making contrived music. When I made that album I thought “I’ve got to do something like this,” rather than letting the process happen. It was done in the upheaval of the whole punk era and it was kind of confusing for me because I didn’t like punk at all at the time. I remember going to some shows in London and seeing these punk bands and not liking them because playing wasn’t an issue. It was more about making a statement and being as much of a rebel as you can. I was confused and insecure about the whole punk thing because my whole criteria of how well you do or what you need to be musically successful was always about how well you could play, how well you understood your instrument and the facility you had. Clearly, the punk era was not about that, so Face to Face became a bit confused as a result.

I now look back at that period and its relevance and it has a lot more logic to me. I understand it a lot more and now even enjoy a lot of the stuff. In fact, my son is in a very good band playing all over L.A. and they have a really good following. He’s the drummer and a lot of the music is quite punky. It also has a Beatles-esque melodic side.

Let’s move on to Wolf from 1981.

I think I found myself again. I toured Face to Face and opened for Steve Hillage who was the nicest guy in the world. It was great to be on the road with him. It was all about the music and we got on very well. At the time, the punk explosion in England was massive and appeared to be obliterating everything in its path with regards to people having ears at radio stations. I think after that tour, I realized there’s still room. It’s not like people are going to stop doing what they’re doing unless they have a large bolt through their nose. So, I really started to work with a lot of passion when writing Wolf. It was really enjoyable and I got some fantastic musicians to play on it.

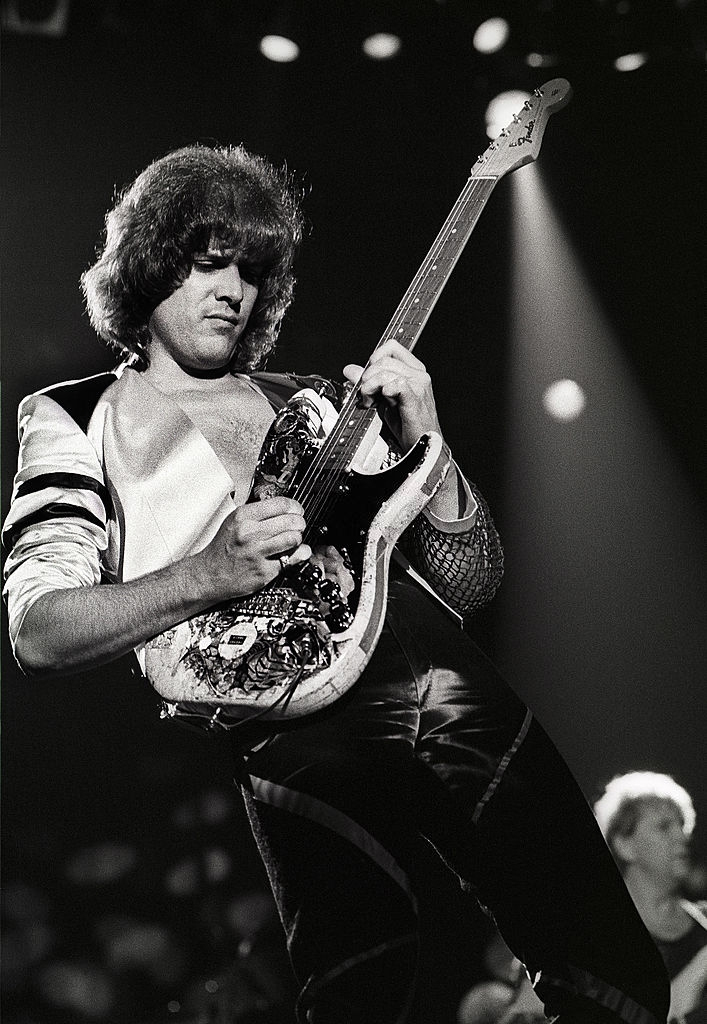

Trevor Rabin, live with Yes, 1984 | Photo: Atco Records

Trevor Rabin, live with Yes, 1984 | Photo: Atco Records

What’s your perspective on 1989’s Can’t Look Away?

That’s by far my best solo album and the one I’m happiest with. I’m happy with a lot of moments on Wolf, but there are moments I don’t like and think “God, I wish I would have known then what I know now.” Every album I’ve done, be it with Yes, Rabbitt or my own stuff has moments like that. I still have the same feelings with films I’m doing too, but I think I have less feelings like that about Can’t Look Away than anything else. I think the quality of the album is better than all the others.

Can’t Look Away seemed destined to be a blockbuster, but it got lost by the wayside.

I think you’re right about that. Initially, there was a feeling that it was going to do well. I was a little disappointed because I thought it could have done better than it did. Having said that, I wish I could say the record company didn’t do their job, but in fact, they actually did a spectacular job in trying to promote it. I really felt they believed in it and got it onto AOR radio in America. It was doing really well. “Something to Hold On To” was number one for three or four weeks. You couldn’t turn on the radio without hearing it. So, I was quite puzzled that it wasn’t translating into sales, but they thought it would pick up and that we should just carry on. I’m glad we did. The video was nominated for a Grammy, not that it means anything creatively, but it meant something from a point of view of momentum. It seemed to definitely be one thing which led to us doing the tour, which is one of my favorite tours. Yeah, it’s a little confusing the album didn’t do better than it did.

The new Live in L.A. CD should help give Can’t Look Away a little more attention.

I think the Live in L.A. album puts Can’t Look Away’s material in its best light. We had a lot of fun at each and every show during that tour. There was only one show where it didn’t go well or sound very good. Ninety-five percent of the shows went spectacularly well. There was such a great vibe in the audience. It was all about the music and we had a really great time.

The album captures the audience’s enthusiasm pretty dramatically.

Yeah, the audience is pretty high in the mix. I don’t mind that some of the definition of the instruments was compromised a bit. It was a balancing act. I wanted to bring the audience into the record as much as possible, but I didn’t want it to sound completely murky. I still wanted definition and separation between instruments. I think I was pretty successful in doing that.

You once said you felt more alive performing onstage than doing anything else. Given that, why haven’t you made the space to perform in more than a decade?

There is a Zen kind of thing that happens when I’m writing for film too. The first film I did was more of a curiosity than anything else. The first couple of films involved a real grueling kind of process, but I liked the collaboration. I also wondered if I would miss playing live because now everything is going to be worked out and organized, rather than having the spontaneity to just play. And when you’re writing film stuff, you have to write every day. If you’re a procrastinator, it’s the best cure, because you cannot be one. Writing for film has the same kind of immediacy and Zen-like feeling as performing, so I still manage to get to that place with time standing still. I think that’s taken the place of playing live. There are times when you’re playing live and it’s not going well and you’re not focused—or you’re too focused—on what you think you should be doing. That can be a problem. But when you’re in that moment, there’s nothing like it. After 20-odd movies, I’ve found that with the last 13-14 of them, I’ve been able to go to that place and really, really enjoy it. That’s not to say I’ll never play live again. I do miss it, but I manage to go that place in a different way now.

There’s rumor going around that Squire has approached you to perform live with Conspiracy.

Not really. Chris and I are very good friends. We’re like brothers and we’ve had our disagreements, but for the most part, I’ll do anything for the guy. I think it’s mutual. We’re good friends musically-speaking as well. As far as Conspiracy goes, there have been times when we’ve discussed a lot of things. There was a time earlier on when he approached me and talked about me coming back to Yes. So, we’ve talked about many things and Conspiracy is possibly one of them. I don’t remember a specific discussion about it.

Squire once claimed you told him you’d rather be in Yes than be a film composer.

Not true. [laughs] Definitely not true.

Let’s get you to set the record straight on another rumor that won’t die. It has been said that prior to the Union record, a Yes line-up convened with Billy Sherwood on lead vocals and recorded an album for Atco that was rejected by the label.

Absolute nonsense. I’ve heard a version of that story that was somewhat similar and it’s completely not true. After Big Generator, there was a time when I was exhausted. It was before the Big Generator tour. I don’t think any one person can be blamed for what happened. 90125 came out, which is to this day by far the most successful record the band ever did. I think Big Generator is also one of the most successful records the band has done. Anyway, you need to consider how Jon [Anderson] came into the band during 90125. It wasn’t like all of us went into the studio, wrote some songs and recorded them. 90125 was a very peculiar kind of creation. When it was time to do Big Generator, suddenly we have these five guys, along with Trevor Horn, who had to figure out how to work together as a band. I think that led to some pulling and pushing. But then I listen to “Shoot High, Aim Low,” “I’m Running” and even “Rhythm of Love” and think it’s all worth it. I think “Shoot High” is my favorite moment on the record. To this day, I still enjoy it.

What was Yes up to when Anderson left to form Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe?

After Big Generator, we didn’t really talk about it much. We were all just exhausted by the whole thing. I went off and really wanted to do a solo album, so I did and that’s when it all started to stop. Then Roger Hodgson and I met and we started working. We probably have enough material for an entire album or more. We were really enjoying working together. Now, I think this part is vaguely accurate. Chris started looking around to see what we were going to do with the band. Jon had gone on to do ABWH, but there was never a discussion about me leaving or Yes being over. Yes just kind of dissolved or evaporated for awhile. Obviously, I was heavily concentrating on the solo album and Chris was talking to people. We thought if we were going to get this together, we should be looking. Chris was really the guy who held the fort up while I was off doing my thing and Jon was doing his. One of the ideas that came up was Steve Walsh. We actually played with him. He’s a talented guy but not the right thing for the band. There were other ideas too. Billy Sherwood was one of those, but we never recorded anything.

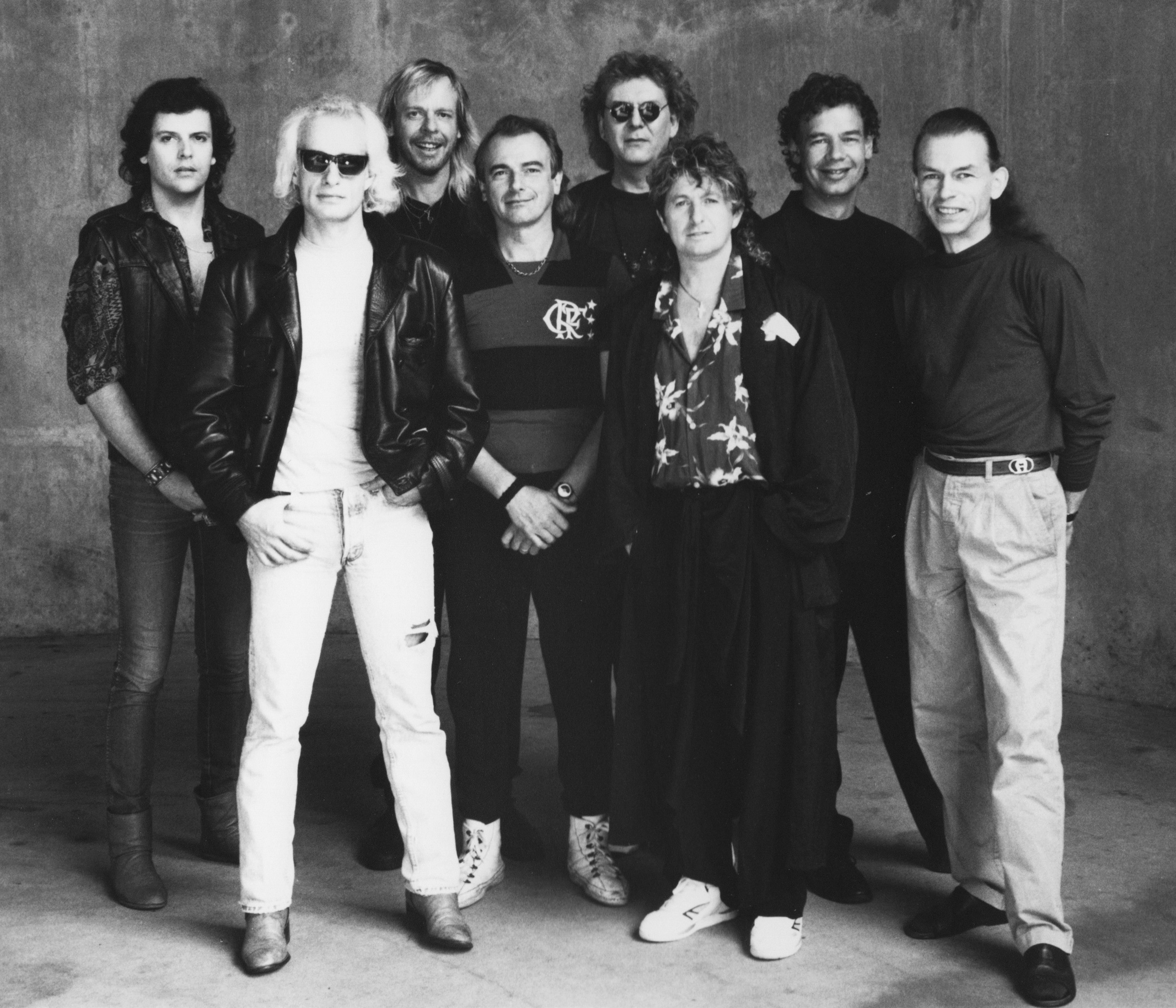

Yes' 1991 Union lineup: Trevor Rabin, Tony Kaye, Rick Wakeman, Alan White, Chris Squire, Jon Anderson, Bill Bruford, and Steve Howe | Photo: Arista Records

Yes' 1991 Union lineup: Trevor Rabin, Tony Kaye, Rick Wakeman, Alan White, Chris Squire, Jon Anderson, Bill Bruford, and Steve Howe | Photo: Arista Records

What’s your take on how the Union line-up emerged?

Well, my first contact was Jon calling me kind of out of the blue and saying “We’re doing a second ABWH album and we’re looking for songs. If you have any material, we’d love to listen to it.” I was still busy with Roger, but then Elektra approached me. Then my manager approached me asking me if I have any songs for the ABWH thing. I said “I’ve got some songs, but they’re not really songs I want to give to other people. I want to do them myself. I’d like to be involved with them and obviously, I’m not going to be involved with ABWH.” [laughs] So, that’s how it was from my point of view. How it worked for everyone else is obviously very different.

I don’t know what led to ABWH looking for songs. I guess the record company didn’t think they had a single. I think that was the issue. So, one thing led to the next and I sent a couple of songs to Clive Davis. One of those was “Lift Me Up” which I had written with Chris. Davis thought it was a single and a strong song and that’s when all the discussions with the suits started circling around this idea of getting the Union thing together. It really had nothing to do with the band.

When they first approached me and said this is what they wanted to do, I said no. It was very clear to me that this is not the right thing to do. I didn’t even know what the ABWH stuff was. I’d never heard it. I didn’t want to be on this kind of compilation record. [laughs] So, my initial reaction was no. Then Chris said he’d gone in and done a lot of work on the ABWH album vocally.

Without telling you beforehand?

There was no intrigue. He just said “I’ve done this and I think maybe this stuff could co-exist.” Then, I was in the middle of writing “Miracle of Life” and one thing led to the next and I ended up saying “Alright.” “The More We Live” came up too and that’s where I met Billy. I actually sang it initially and then Jon heard it and liked it, so he sang it and did a magnificent job. So, it was looking like this could be kind of cool, but the idea seemed contrived and was coming from guys spinning dollar figures. I don’t think there was anyone in the band who thought it was a great idea, musically speaking. I think Jon and Chris hoped it would work. We all did. I had no idea. I’d never met Rick [Wakeman], Bill [Bruford] or Steve [Howe], so everyone was concerned about how it would work. It was easy as far as the record went. By the time it came out, I still hadn’t met them. We still hadn’t spoken.

It must have felt very odd when Anderson called to ask you for ABWH material.

It was good to hear his voice after so long. [laughs] It was interesting, because I was also working with Roger who stylistically also has the same high, angelic-sounding voice. I remember thinking as he said “Trev,” “Wow, is that Roger or Jon?” I wasn’t quite sure. We had a nice conversation. When he asked about the songs, Jon said he felt the album wasn’t completely rounded off and he wanted something else in there—probably a single. I didn’t look at it cynically in any way.

The perception is that the remaining members of Yes felt betrayed by Anderson leaving for ABWH.

No, not at all. Not from my point of view anyway. There was a time when ABWH went on tour and Brian Lane was managing the band. We found out they called it “An Evening of Yes Music” and Chris was really upset about that. We went to lawyers to see if this was something they could do or not. Chris felt they shouldn’t be doing that. The band wasn’t called Yes. We were still officially Yes and there was no reason to allow it. Once the Union thing happened, I don’t think there were too many feelings of mistrust.

The press statements at the time of your departure from Yes made it sound like you had an amicable split with the band, but Wakeman said “I think there weren't just bridges burnt with Trevor—they were blown up with terminal destruction.“

[laughs] That’s so Rick. Rick and I have a real rapport from my point of view. I love the guy. He’s one of the finest people around. Not that long ago, he approached me to work on his Return to the Center of the Earth project, which I had great fun doing.

I honestly believe there’s such an overblown idea of the personality clashes between me and Jon and Tony. I like Jon and enjoyed working with him. I think his voice is extraordinary and there’s only one of them. But when you’re in a creative environment and you’re passionate about what you do, there are going to be arguments and disagreements. Unless you’re a guy that sits there and goes “Yeah, that’s fine then, of course,” there are going to be those moments. And if that’s the case, then what are you bringing to the table?

There were disagreements that happened during and after Talk, but if you speak to Jon, he’ll tell you the Talk album was a positive moment for him. I think he enjoyed it. It was one of the times when I went to a holiday resort on the coast here and Jon and I got together for quite some time. We wrote, talked and walked on the beach and had a great time.

If you do an album like Face to Face and it doesn’t happen, I can look at it once I’ve done it and say “Okay, you know what? I’m going to work so hard on the next album to get it right and make it something I’m absolutely proud of.” But when I finished the Talk album and completed the last mix and handed it in, I thought “Okay, I think I’ve got to a point for myself where I’ve reached as high as I can go at this time.”

I think when I do another record, which I want to at some point, I have to make a better record. The word “better” is a weird word. It’s such a subjective thing. When you do a record like Talk and you’re happy with it and it reaches your ambitions and then doesn’t sell as well as you wanted, it kind of takes the wind out of your sails a little. I thought “Well, I don’t know what to do now. I guess Yes can go and do another single, but we’ve gone through that. Now, it’s a matter of making albums that can stand there on their own—albums you can listen to like a symphonic work or something of that nature.” I thought Talk had done that to a degree. So, it was a confusing time for me. I needed to catch my breath. I think I was claustrophobic after Talk. Having said that, the Talk tour was the one on which we played our absolute best. I guess they call it the 90125 line-up or Yes West line-up—you know, these silly names people have for different incarnations of the band.

Yes, 1994: Alan White, Trevor Rabin, Jon Anderson, Chris Squire, and Tony Kaye | Photo: Victory Music

Yes, 1994: Alan White, Trevor Rabin, Jon Anderson, Chris Squire, and Tony Kaye | Photo: Victory Music

The one curiosity about Talk is why you edited out the ambient section of the album version of “The Calling.”

[laughs] That was the band being weak and not standing up and saying no. I primarily blame myself for that. I should have stood up and said “No, I’m not going to do that.” But there was such a push from the record company to cut it down for a single. Instead of saying “Well, alright, let me try and find a way,” I should have cynically said “Oh, what a great idea! What a unique idea to cut it down. It just makes sense!” I can just see the A&R guy sitting in his office thinking “What am I going to do today to justify my job? Oh, here’s the Yes stuff. Let’s cut this down.” It was a butcher job and lacked finesse and a real reason for doing it. One of the things I’m least happy with is how we cut that down.

What do you make of the fact that you’re still a topic of debate and speculation with Yes fans after leaving the group a decade ago?

I’m fast approaching my 50th birthday and as I do, I reflect in a more overview-ish way. I was in Yes for 14 years and I’m very proud of what we achieved, even though things took a long time to get done. I think the most successful times we had were the shows, not the records—although I’m insanely proud of the records. I loved working with the guys and playing live with them. There was one show in Rio with 400,000 people in the audience. There were moments during that show when if I had died right then, I would have said “Well, this is the transition to heaven.” It was that extraordinary. I think people overplay the personality difficulties the band had. There are always differences of opinion with people that are creative and have different ways of getting to places. But I still have enormous affection for Chris, Jon and Alan—and Rick as well.

I think one of the misconceptions about the band is the kind of stereotyping that goes into the different line-ups—you know, like people saying my line-up was the one with the pop songs. [laughs] That couldn’t be further from the truth. Some of the things we tried and some of the weird places we went aren’t talked about much. I think songs like “I’m Running,” Shoot High, Aim Low” and “Endless Dream” more accurately reflect what the band was about when I was in it than “Owner of a Lonely Heart,” though that song stands out as a moment that defined where the band was going.

I would have hated for people to say “When Trevor came into the band, he fit right in and it sounded just like it used to.” When I’m on my last breath, I’d rather be seen as something a little more catalytic in terms of what I brought to the band.

You once referred to the process of writing film scores as “selfish freedom.” The outsider perspective, even amongst musicians, is that it’s an arena of constraint and compromise.

Well, there are compromises in being in a band too and there should be. That’s what being in a band is about. There are pros and cons to everything. There’s a real loneliness to being a solo artist unless you have a unique relationship with the people you’re working with. The compromises in Yes were beautiful ones. I’ve heard it said the perception of the 90125 band is that I wasn’t a collaborative kind of guy. I think that couldn’t be further from the truth. The 90125 album emerged from months and months of rehearsals and trying different things. It’s not like I came in with a bunch of demos under my arm with a lock on them and said “No-one can get in here.” If you look at the credits, people got involved from a writing standpoint. I always felt inspired working with Chris and Jon. I always felt energized working with them. It was a very good thing for me.

With film work, I feel the same way. There’s a camaraderie and collaborative thing that happens. At the end of the day, you have to adhere to the vision of the director, but in the same way, when you’re in a band, you have to adhere to a collective spirit that might not be about the feeling you want to put across as an individual. Again, that’s what a band is all about. That’s what makes it so exciting. But it’s a very different kind of collaboration.

When I’m sitting and starting to write, that is the moment I like best. It’s very inspiring. The compromises are more that I might write the best piece of music on a piece of film and it’s the one you’re going to hear the least because it’s over a big chase scene or something. For the movie Deep Blue Sea, I wrote something in 17/8 and I did it with a 90-piece orchestra and an 80-piece choir. Everyone was so excited when we finished doing it. Then the movie came out and you heard the sound of water splashing around louder than the music. Once you reconcile that and put aside that selfishness, you have to enjoy the moment. When I finished writing the music for Deep Blue Sea, which was basically about monster sharks, the moment when that stuff was done was very, very exciting. It was done primarily with the L.A. Philharmonic, who are all great players. They came up to me afterwards and told me it was a very exciting project. That was great to hear.

Are you happy with the way you’re typically represented on the soundtrack score albums?

It’s a very difficult thing because a film usually involves a lot more music than is on those CDs. Sometimes there’s a lack of time to really structure them as an album. So, in some ways, if you watch the film from start to finish with the dialogue off and just the music, you get a better idea of what the music’s doing. That’s not something you can do very often. I’m not even talking about having the picture on—just the running order of how the music happens. If you edited that, so it was in that order and played it, it would make more sense. It would be more true to the pacing and rhythm of the film. When you put a score album together, you’re taking what you feel are the strongest moments and stuffing them together. It doesn’t always flow in the best way, but I’m happy there’s some kind of documentation, album-wise, of some of that stuff.

Which of your film soundtracks are you most proud of?

Deep Blue Sea and Remember the Titans. Unfortunately, there wasn’t a score album for Titans. Some of the music I’ve recently done is what I’m most happiest with. I’ve been doing something with a director called John Dahl for a Miramax film called The Great Raid. It’s about a true story during World War II in the Philippines, dealing with prisoner of war camps and the rescue of some of those prisoners.

Was it a vicarious experience to create the soundtrack for the movie Rock Star?

[laughs] It’s funny you ask that, because at the very start of the movie, there was a bunch of people at a show and the replacement singer comes on and they hold up a banner saying “Bring back Bobby Beers,” who was the original singer. That brought back memories of my first couple of Yes shows where there were people with signs saying “Bring back Steve Howe.” My approach to dealing with that was different to Mark Wahlberg’s. He stuck his finger up and sprayed them with water. By the end of the show, they were sufficiently impressed or happy and tore up the banner and threw it on stage. I had the same experience. I didn’t put up my finger to anyone, but played as well as I could and at the end of it, they also tore up the banner and threw it onstage. So, it was an interesting similarity. The film also captured the adrenaline you have backstage before the show. It reminded me of what I wasn’t doing anymore.

How do you look back at working on that film?

It was a difficult film. I’m happy with what I did. I couldn’t get in the way of the rock and roll. I couldn’t play against it. A traditional orchestra score wouldn’t have sat well with the personality of the film. I couldn’t do anything to counter the heavy metal stuff, but I couldn’t do anything that was like it. So, it was quite difficult to find the voice for it, but once I did, it went quite smoothly.

Yes receives gold records for 90125, 1984: Tony Kaye, Jon Anderson, Hans Tonino of WEA, Alan White, Trevor Rabin, and Chris Squire | Photo: Atco Records

Yes receives gold records for 90125, 1984: Tony Kaye, Jon Anderson, Hans Tonino of WEA, Alan White, Trevor Rabin, and Chris Squire | Photo: Atco Records

Contrast the visceral thrill you experience when having a hit single versus a hit movie.

I’ll give you a specific example. 90125 sold 6-7 million records and “Owner of a Lonely Heart” was a number one single. It was a tremendous feeling to know you’ve done something that’s far exceeded anything the band has done before. It was confirmation that we’ve done a good thing. In contrast, I did the Armageddon score and the movie was hugely successful, making hundreds of millions at the box office. The Armageddon soundtrack sold many more copies than 90125. I only had two tracks on the album and they were score tracks, but the feeling was quite similar in a strange way. With 90125, it’s all about the band, the music and the work you’ve put into it. When a film soundtrack does well, it’s about a lot of things. I still say the excitement of doing a score is finishing the music, listening to it and saying “I’m really proud of that.” It’s obviously exciting when the box office is good too. In some cases, it leads to you having a higher profile in the business and becoming an A-List guy. So, there are different reasons for why it’s enjoyable.

Are the financial rewards greater in the film scoring world than the rock arena?

In my case it is. If you’re doing a couple of HBO specials a couple times a year versus if you’re Michael Jackson, then it’s a bit like asking “How long is a piece of string?” But it’s been good to me.

Does your current lifestyle afford you the opportunity to positively experience family life in a way you couldn’t previously?

In a way, yes, because I’m home, but I’m so busy. I’m much busier than when I was doing the other stuff. For Bad Boys II, I was working 16 hours a day. You can work for six weeks, working every single day without one day off. It can be relentless. Keep in mind, when you’re writing film stuff, there’s a large amount of technical criteria that has to be taken into consideration. You’re writing for specific moments in the film to a precision of a 30th of a second. When you start a piece of music, you might say “I’m going to start it here, when he closes his eyes at two hours, 30 seconds and 11 frames. That’s where I start this cue and I’ll end it at 18 seconds and nine frames later.” You really have to hit that level of precision. You also have to take into consideration the tempo. So, there’s all these mathematics and equations mapping out what goes where.

I think that’s why it’s so enjoyable when you finish something and it sounds smooth, cohesive and coherent, yet you’ve managed to drive the picture. So, there’s a lot of things that are really satisfying about film work, but it’s very complicated compared to writing music for a record.

I’m lucky. I’m in a position that lets me do movies with big budgets, but with that comes responsibility. It’s great because when I say I need a choir budget, it’s not really an issue. If I say I need a 60-piece Native American Indian choir or a Bulgarian choir they say “Fine, whatever you need.” I’m lucky to have people trust me enough or who are silly enough to allow me to do that.

How do you think your film work might influence the direction of a new solo album?

I think it will influence it more significantly than anything I’ve ever done. The thing I never did in a band, be it Yes, Rabbitt or Freedom’s Children, was explore my love for orchestra. I really had a desire to conduct, arrange and write for orchestra and that was put aside. I did a movie when I was 19, long before MIDI or anything. My wife and I went to a resort and took a projector and projected the movie on a sheet. I sat there with manuscript paper. It was a terrible film, but I was very young and had just finished studying orchestra. So, it was very exciting to be doing a film and working in a large way with an orchestra. Times have changed with MIDI and things can be mocked up effectively now. In the old days, you had to do it on piano to give them an idea of what it’s going to be like. Now, you can pretty much show them exactly what it’s going to be like once the orchestra does it. Having spent so much time working with orchestras now, it’s something I would want to integrate into a new solo album.

The most important realization of doing film is the freedom of going from one genre to another. It’s a very powerful feeling. In a band, you’re somewhat stifled by whatever your style is. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but with a film like Armageddon, which is larger than life, you’re writing the world anthem for 80 minutes. That gives you amazing freedom to be able to create without concern for “Where I am going with this?” I think the film thing has allowed me to open up to so many opportunities. No longer is it “You can’t put this here. We’ve never used that before.”

Will it be a singer-songwriter album?

Probably not. I think I’d sing on it, but it would be far more instrumental. The previous solo albums were very much singer-songwriter efforts with me delivering a lyric and performing as a guitar player essentially. Now, I think it would be a little more eclectic and a lot more natural maybe. It wouldn't stick to a certain genre. I wouldn’t do what I’m expected to do. I think it would be a lot freer.

When do you think a new album might materialize?

I’ve got some movies to do and then my intention is to go in and do that. But if I get a call from someone I’m excited about working with, it’s very difficult to turn down. It’s one of the very exciting things about doing this. Thankfully, I’m in a position where I get asked to do a lot of films and I get to work with some wonderful people. It’s hard to say “No, I don’t think I’m going to do that. I’m going to buckle down and do an album.” I’ve got quite a lot of material together that I’m happy with. When I get enough together I’ll start to do an album. I want to start the flow and have the next album be a very positive experience that represents what I want to do. Hopefully it’ll be done sometime in 2004.

You mentioned a band you were in called Freedom’s Children. What can you tell me about it?

Freedom’s Children was one of the first really important progressive rock bands in South Africa. It started off with another guitarist and bass player and they disbanded. The bass player from Rabbitt and I joined and started a different thing. It was pretty much an anti-apartheid band. We did a lot of touring and Clive Calder, the owner of Zomba Records, was a promoter who put us on the road. It was an interesting time. The guys in the band were much older than me. I was 18 and they were about 28—sort of like me being in Yes. [laughs] We made a record called State of Fear which was never released and then the band broke-up because by law I had to join the army. It was a really sad moment for me because I was really enjoying it, but when I came out of the army, Rabbitt happened, so I can’t complain.

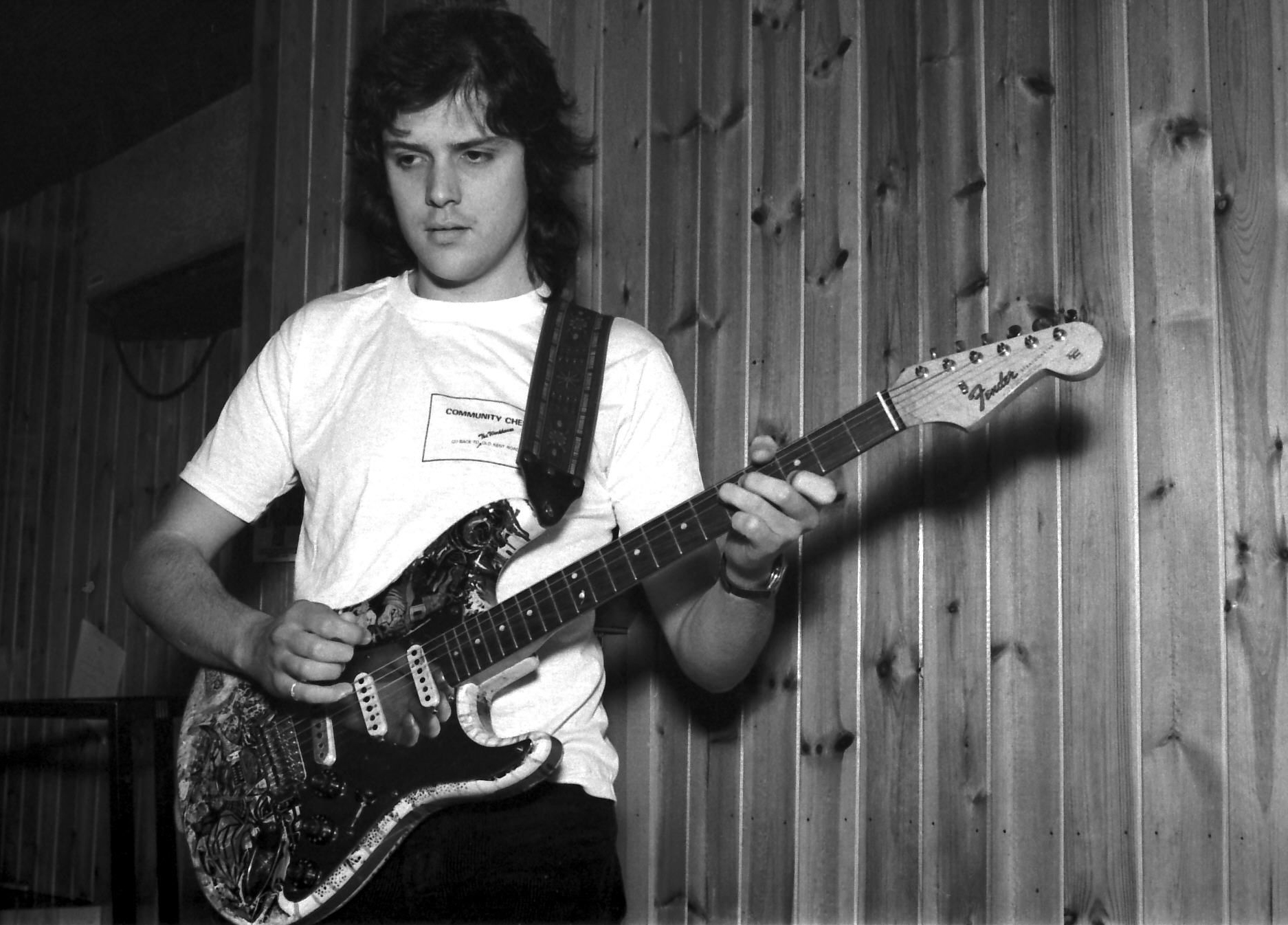

Trevor Rabin, 1975 | Photo: Capricorn Records

Trevor Rabin, 1975 | Photo: Capricorn Records

How do you look back at your years with Rabbitt?

I was a teenager and it was a really interesting time. I was very young, naïve and took things for granted. At the time, I was a session guitar player, doing some production, as well as a lot of orchestra arrangements for other people’s records. There was a feeling of being sought after as a session musician, so I had a lot of unwarranted confidence at the time, which led to Rabbitt being very cunning. We pushed ourselves quite hard, but we did fine.

It was an amazing moment in my life. We were suddenly faced with intense fame in this small country. It was pretty peculiar. The one thing that was different about Yes is that it was a pretty faceless band, except to Yes fans. The only guy from the current band to other members from the past that would be recognizable for the most part would be Rick. People who aren’t into Yes don’t say “Oh, isn’t that the guy from Yes?” It’s not like being Rod Stewart. Rabbitt however, was on the cover of magazines and newspapers daily. We couldn’t even go shopping or to the movies.

Rabbitt live was a very good band. On record, we did a specific thing because it was a difficult time in South Africa. There was no such thing as a white band putting out a record of original rock and roll or progressive rock, or pop music for that matter. We were the first band to really do it. There were moments with pop records from other people, but to put out a concept record as Rabbitt did was unheard of. The record company stuck out their necks for the band and we did very well from it.

What was it like being a white South African musician espousing anti-apartheid views in public at the time?

There were no real repercussions for what we were saying. You think there would have been. My cousin Donald Woods, the guy who wrote Biko, recently died. And Sydney Kentridge, the barrister who prosecuted the government on behalf of the Biko family is also my cousin from the other side of the family. So, I come from a family that was vigorously involved in anti-apartheid activities. My father was hugely anti-apartheid. I never grew up thinking what was going on was natural. I remember my dad saying to me “Look, you need to do well in school. You need to do well in history. I want you to learn the history, but I want you to know it is not accurate.” He would point out the things that are inaccurate and how they are completely politically motivated and trying to put across a specific view of the way things went down during the Boer war. So, I had a very interesting upbringing.

Do you think your legacy will focus more on being a film composer or a rock musician?

I think it’ll be as a musician that did a bunch of different things. It isn’t very profound, is it? [laughs] I think there are moments that I hope are pivotal in my life and hopefully anyone looking at them will deem them important. I do think in the long run that Talk will be looked upon as the most important album I did with Yes. Right now, it’s disregarded in a lot of ways from a commercial standpoint. It didn’t sell as well as the other records I did with the band. That never had anything to do with whether a record is good or bad. It never does. It’s just one of those things when a record does well. I’m very happy about the record. I’ve had records do well that I’m not creatively happy with. I’m happy they did well though. These two things don’t coexist naturally or automatically. I’ve still got a lot of work to do. It’s been an interesting life and journey so far.