Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

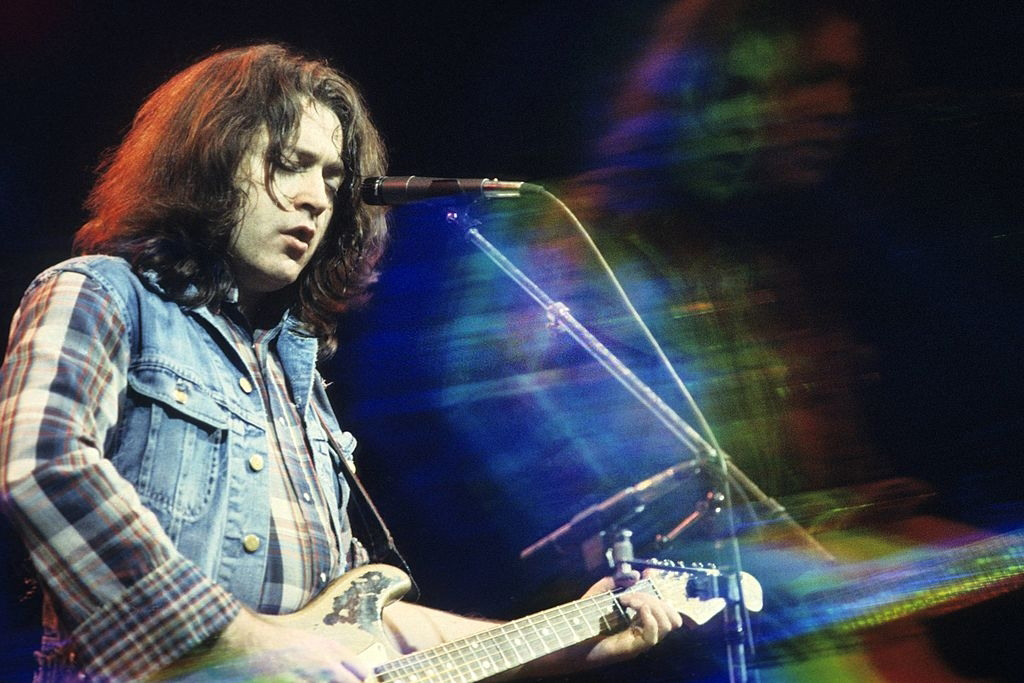

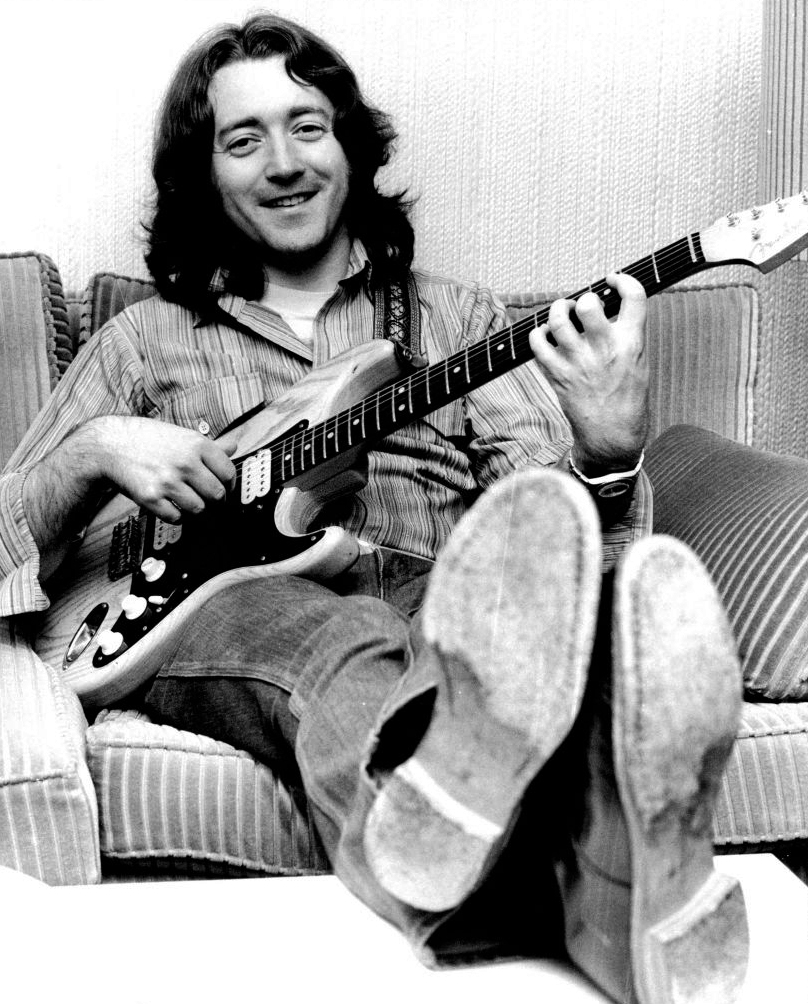

Rory Gallagher

Outside the Establishment

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1991 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Capo Records

Photo: Capo Records

Rory Gallagher’s contribution to the evolution of blues-rock was extraordinary. Throughout the course of his 30-year career, the Irish guitarist and singer-songwriter brought unmatched integrity and passion to the genre. Unlike contemporaries who went the blues-pop route, Gallagher never watered down his sound. He remained content to deliver album after album of scorching performances drenched with rollicking guitarwork and gritty vocals, inspiring generations of musicians to stay true to their instincts. With more than 30 million records sold, he also proved that an uncompromising approach could also be a wildly successful one.

The self-taught musician first hit the limelight as the leader of Taste, an enormously popular late '60s power trio that incorporated folk, pop and jazz into a blues-rock base. Following the group’s demise in 1970 due to internal tensions, Gallagher embarked on a celebrated solo career. The ‘70s and early ‘80s saw him release several landmark solo albums including Tattoo, Blueprint and Calling Card. Other highlights included his work on records by legendary bluesmen Muddy Waters and Albert King. The rock guitar fraternity also took notice, with Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and Paul Rodgers all citing Gallagher’s work as a significant influence.

The mid-to-late '80's weren't as kind to Gallagher. Faced with record label disinterest in the face of changing musical tastes, his album sales and audience declined. That started to change with the release of 1990's Fresh Evidence. The disc lived up to its name as it delivered one of the most diverse and engaging collections of his career. The album explored a wide variety of blues styles and found Gallagher stretching out on instruments such as dulcimer, electric sitar and mandola.

Gallagher passed away in June 1995 at age 47 from complications following a liver transplant. His body failed him, but his musical soul continues to triumph in the hearts and minds of legions of fans around the world.

This interview, conducted during the Fresh Evidence tour, finds Gallagher using the album’s songs and production ethos as a springboard to to explore the broader philosophies that informed his life.

Photo: Capo Records

Photo: Capo Records

Tell me about the approach you took when recording Fresh Evidence.

It took enough out of us, I can tell you. It took about six months to make, which is quite a long time really. It sounds like relatively simple music, but we were trying to get a good vintage, ethnic sound in the production and everything else. We used a lot of old valve microphones, tape echo, old spring reverbs and things like that, instead of using all the digital equipment. We used a valve compressor as well, which gives a different effect than modern compression. We used a few modern tricks as well, but just enough to help out.

Some of the songs are quite long and somebody else would have edited them and taken out verses, but I just left everything as it was. I can usually get the backing track or the feel on the first take or two. I think it’s in the mixing and overdubbing areas that I'm more of a perfectionist. We cut the Fresh Evidence master about four times. In a perfect world, I'd like to walk in a room and just play it once and have it all perfect. You're at the mercy of the engineer, and the sound, and the room, the desk and everything else.

Why did you choose to cover Son House's "Empire State Express?"

I had the record for years and I just fancied that song because I thought I could interpret it reasonably well. I went into the drum booth and just used the two microphones and recorded it in one take, live. Mentally, I put the gun to my head and said "This is the way it has to be done." It came off fairly well. The strange thing about it is I lost the record about a week before I was going to record it. Not that I was going to copy the record, but I wanted to listen to it again and check it out. But I had the lyrics written down in a book anyway. So I recorded my own arrangement from memory and it turned out okay.

The situation may have worked in your favor. Too many blues covers are simply clones of the original.

Yes indeed. If you just ape the old record, then it's a one-dimensional thing. I try to adapt and interpret the songs at the same time. It’s good to capture the original feeling, but there's no point in doing it just verbatim. I know certain guys who do that and it doesn't get them anywhere. But then some ultra-purists feel you shouldn't tamper with these songs or even attempt them. I think it's one way of keeping the music alive and bringing it another step forward.

Son House’s importance seems to have been eclipsed by the renaissance of interest in Robert Johnson.

It's unfair really. As great as Robert Johnson was, "Walking Blues" and "Preachin’ the Blues" were written by Son House. He also gave lessons to Robert Johnson. With this great boost to Robert Johnson, maybe they should bring more attention to other artists who were nearly or equally as important. But Robert Johnson has the mystique, the death thing and the devil connection.

Do you believe in the Robert Johnson mythology?

I think it's possible. I heard the same thing about John Lennon—that when he was in Hamburg, he made some kind of deal. And if you look at his death and his effect on people and life in general, you have to wonder, but then I 'm a little bit superstitious anyway.

How does being superstitious affect your life?

It has affected me very much in the last 10 years. I get it from my grandmother. She was very superstitious as well. I'm funny about numbers. It's become a phobia, so I have to watch it. It affects your day a lot. Before I go on stage, there are certain things I do that are semi-sort of Gypsy superstitious things, but I'm coping with them. It hasn't affected the music, thank God. If you got really bad, you'd say "I'll pick that note instead of that one or sing this song before that."

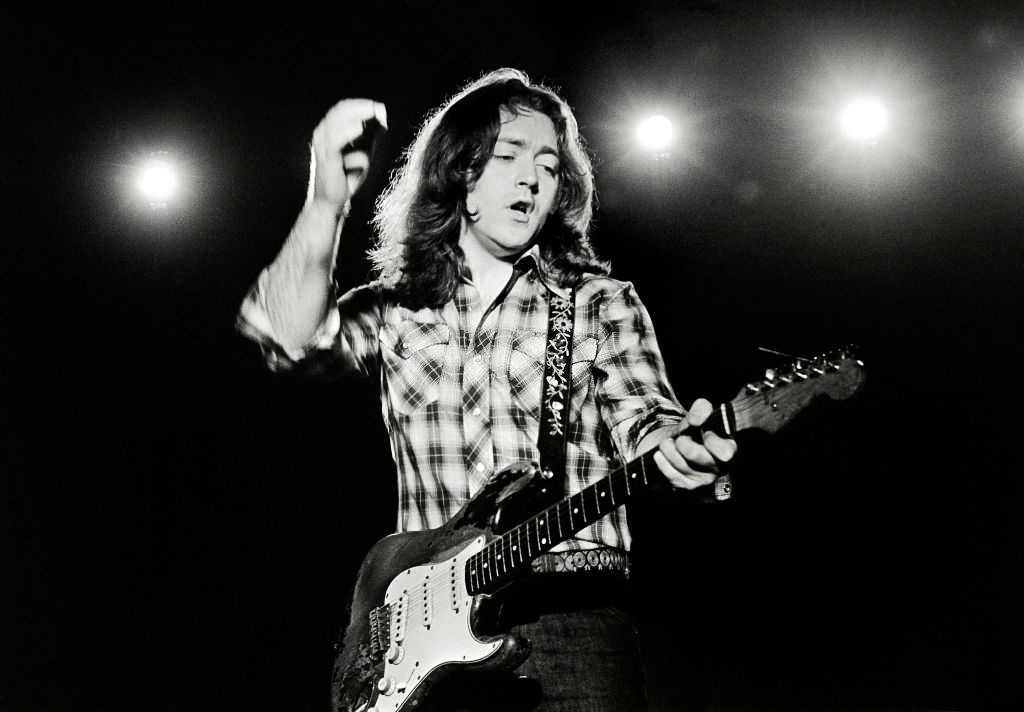

Photo: Capo Records

Photo: Capo Records

Are you a spiritual person?

I suppose deep down I am. I certainly don't think we're on this planet just revolving with nothing out there. When you’re in tight corners, you can come to the realization that you have some kind of a belief. I'd say I do, but I don't preach about it and don't make a big thing about it. I don't think it's a bad thing in the end. I'm too scared not to be, let's put it that way.

"Heaven's Gate" shares several qualities with classic blues numbers.

That's close to the idea of "Hellhound On My Trail" by Robert Johnson. It's a man being haunted in a room in a terrible condition. It's a semi-redemption type of song and it's also slightly preaching to people that you can't bribe St. Peter. It's in the blues tradition even though the song is in my own sort of style. The lyrics kind of speak for themselves—somebody going through a very bad patch and facing up to mortality and all those sorts of heavy things.

What did you write "Walking Wounded" about?

I liked the title. I had it in my notebook for weeks and then the first couple of lines just came to me. Also, my health wasn't very good at the time. It's not written in the first person as such, but I suppose it's written from the point of view that if you're at a very low ebb, you still have fighting spirit. That’s the basic message in it. The song has a nice riff and a bittersweet flavor to it.

In contrast, "Middle Name" depicts a darker tale.

That's kind of Slim Harpo-influenced, musically. I tried to create an image of being down around the bible belt with a guy stuck in a situation searching for someone that could be his wife or someone else before a big storm or Armageddon or the Holocaust. It's kind of overwrought, but that’s the vibe I tried to create in the thing. It’s a bit of a Tennessee Williams-type of setting really. Like in any of my songs, I tried to keep it from being one-dimensional. It's nice to have an image-and-a-half in a song, at least.

“King of Zydeco" explores your interest in Zydeco music and is dedicated to Clifton Chenier. Tell me about your fascination with his music.

He's sort of the B.B. King of Zydeco music. He played accordion, which is the lead instrument in that kind of music, instead of the guitar. It's kind of blues, but it's sung in French. It's kind of a cross between Cajun folk music and other things and I like the records. I like the slightly sloppy feel to them. I wrote the song about somebody getting away from modern city stress into this mystical juke joint somewhere in the South, like in a road movie. Of course, at the end of the journey there would be somebody like Clifton Chenier playing on a small stage—the perfect gig, in my mind. I saw him perform in Montreux, Switzerland. We both played the jazz festival there a couple of times and he was performing—not on the same day, but we saw him anyway. I didn't get to meet him. He looked hearty. He died quite young really. That's the problem with these shows—you're on the same bill with people and you're either too shy to say hello to them or you say "I'll see them again, surely."

You’ve recorded two albums that were never released. What can you tell me about them?

In 1978, we recorded a complete album in San Francisco and on the day it was being cut I just turned against it. I still have the acetates of it, but I'm glad we didn't release it. I mean, it was adequate—there was nothing wrong with it. I wouldn't call it a bad album. But between the production, the sound and the way it was played, I knew we could do better. In fact, what we did is we went back to Europe and recorded Photo-Finish. Using some of that material, we recorded Photo-Finish in about three weeks instead of spending six weeks or more in San Francisco. The other one I recorded was tentatively called Torch. We made that before Defender. That suffered from the same problems. I was dissatisfied with the sound, the performance and the direction. Sometimes the easiest way out is to just drop the project and to start afresh. Even if you do hold on to some of the songs, it's best to start in a fresh room with a new engineer and make new attempts at the songs.

Recent years have seen a watering down of blues traditions in favor of lightweight blues-pop. What do you make of it all?

I just do my own thing really, but I'd be envious of people who have all these doors open to them and sell a huge amount of records. It doesn't really do to get jealous of anyone, because it gets you nowhere. But sometimes it seems like a very hard road to continue to do what you're doing under the right conditions. Some people do appear out of nowhere and the next thing you know, they are superstars, but I really don't lose sleep over that because I've got enough to worry about in my own little area. I certainly would like to have more exposure and higher places in the record charts. I'm not happy to be semi-obscure, but I'm not going to sell-out just for the sake of getting my face on a magazine or anything.

It’s rare to see media coverage about you that doesn’t mention Eric Clapton as a musical compatriot. Does that frustrate you?

I have respect for Eric Clapton from the early days, but I'm surprised they always link his name with me. Maybe earlier on there might have been more of a comparison, but not at the moment. Clapton seems to be the icon of all guitarists including Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page. I suppose he’s the successful face of what the blues is and I’m probably the guy on the sidelines. He's working in a different area from me now. And even in the blues field, I cover different blues tangents than Eric does. I work in country blues and even though I do some numbers that are in the B.B. King and Albert King area, I work in a lot of other influences in as well. My blues roots are all over the place, where Eric's tend to be a little narrower.

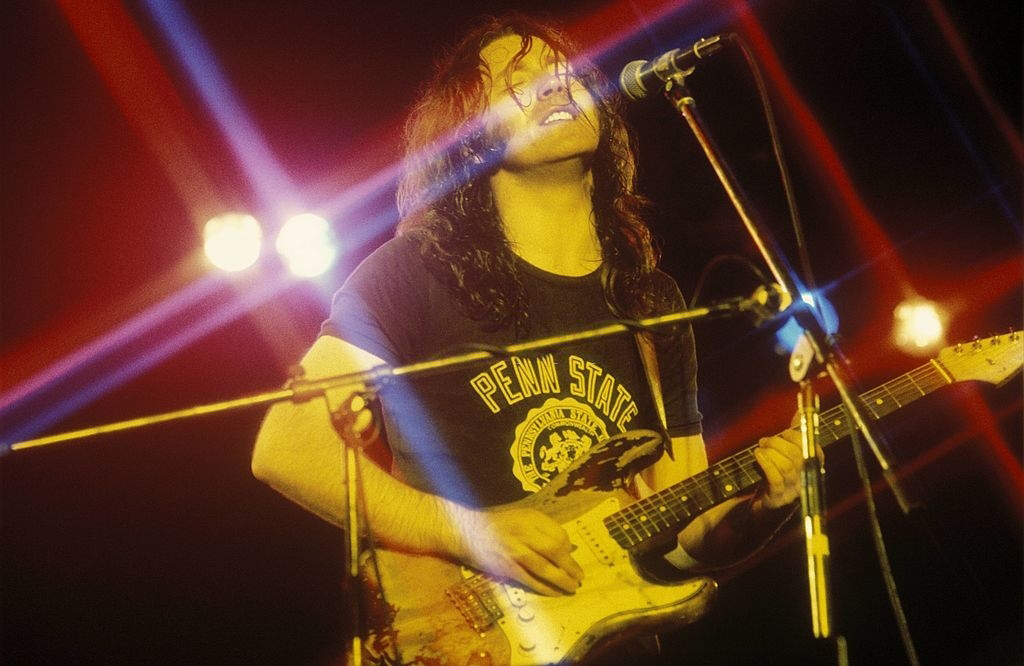

Photo: Capo Records

Photo: Capo Records

Some believe many of the up-and-coming blues artists aren’t paying enough attention to the roots of the music. What do you think?

If you're only 19 years of age and the first electric guitar player you heard was Eddie Van Halen or something, you might think the blues might be Eric Clapton or Jeff Beck. At the very most, you might think of Albert King or B.B. King. They don't dig back further than that. I think if you're a real blues player, you should go back as far as you can and study and absorb what you hear. That said, some of these young guitar players for their age, even though they don't look back that far, have amazing technical facility, but from my point of view, not that much feeling. They have superb speed and can play classical music on the guitar and everything else, but I'm still fascinated by the rawer element of the music.

I'm reasonably optimistic about the future because Muddy Waters had a hit single recently, even though it was because of a jeans ad in Europe. John Lee Hooker also had a hit last year. It obviously isn't 100 percent pure John Lee Hooker. It was kind of a combined effort with other people, but in 1991, I suppose you just have to accept that. There are still a few guys around who are still playing pure blues too. I think I’m a cross between a dyed-in-the-wool purist and someone that likes to be free enough to play things on the fringes of blues. I don't mind rock and rolling. I don't mind a bit of folk creeping in or a jazz phrase or whatever. I think aside from the music, a lot of musicians accept the sort of show business avenues as they are. They don't question anything and they're quite happy to follow the establishment. It must be the old Irish in me—we tend to work outside the establishment, historically and otherwise.

You’ve worked with a core nucleus of musicians for a very long time. Describe the chemistry that’s developed.

Jerry McEvoy has been with me on bass since '71 and Brendan O'Neill’s been there on drums for about 10 years. We also have Mark Feltham on harmonica. He's been playing off-and-on for about six years with me. Generally, it's good to have a line up for a long time. There are arguments for and against that, but on the plus side, you get an ESP thing going. You can also keep the repertoire wide open. We don't do the same set every night. The band just recognizes the song from the chord. I don't even have to say anything. It makes for a very tight show.

You used to play sax on your records occasionally. Is that something you’re still interested in?

I still play it at home once in a while. I'm kind of rusty on it now. I got lazy and concentrated on the guitar more. The last time I played it on a record was on a small bit on the Defender album on a song called "I Ain't No Saint," which is kind of an Albert King-ish sort of blues. I played three saxes triple-tracked on it. I still like the sax and wish I could play it as well as I used to be able to. I also play mandolin and harmonica. I can't really play piano, which is a great pity from my point of view. I can play a lot of other stringed instruments including dulcimer and banjo. Unfortunately I can't read music, and to play by ear is quite difficult, whereas with guitar, you can progress without reading music.

What are your career highlights to date?

Some of the early gigs at the Marquee club in London were important. Also, my first trip to the U.S. and Canada was obviously important. Playing in Hamburg during the late ‘60s was good also, as were some of those big festivals we did like the Isle of Wight. Also, recording with Muddy Waters and Jerry Lee Lewis were big things for me. Getting the last two albums recorded and released were highlights for me too, because the ‘80s weren't really good to me. So, to get into the '90s is a good feeling.

How have you have evolved as an artist over the last 10 years?

Naturally, in 10 years, you change as a person and you learn a lot from your mistakes. You also learn a lot about wasting time and the right way to handle things. We're not touring as much. We're not doing eight or nine months of the year, so I've got a bit more time to get a perspective on what I do. I think I’ve improved my songwriting. I'm every bit as enthusiastic about playing as ever and I'm still learning.