Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

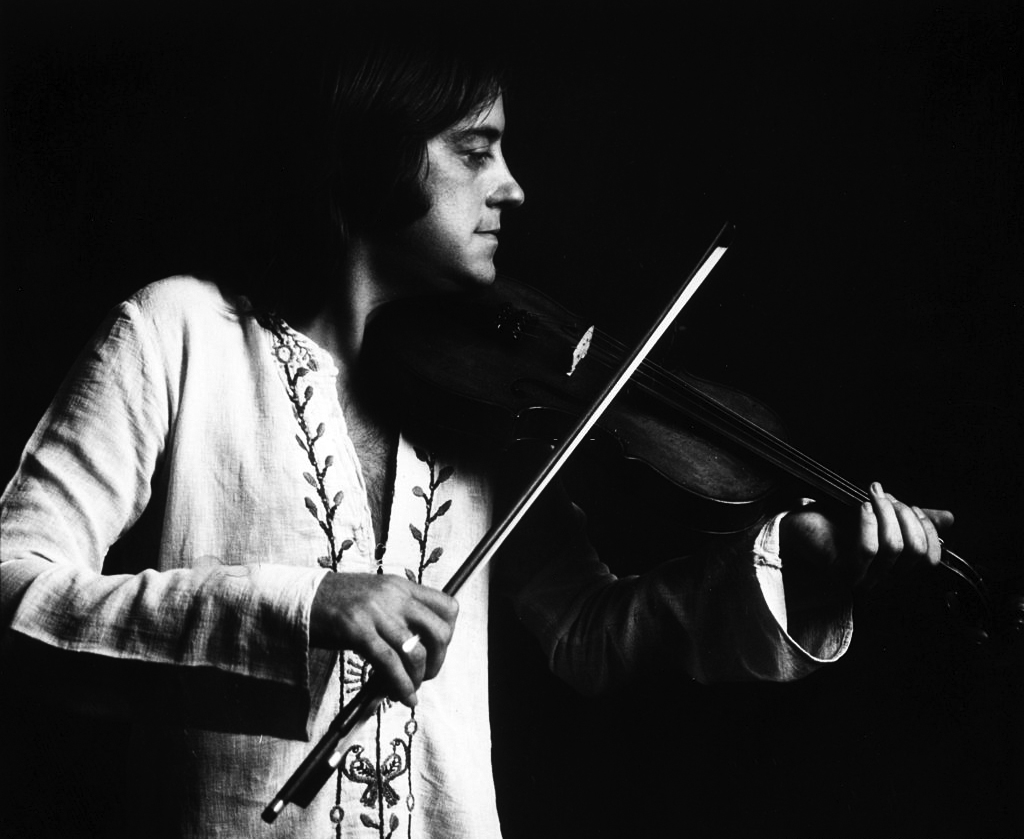

Dave Swarbrick

Bewitched by the Muse

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2001 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Shirty Records

Photo: Shirty Records

In the pantheon of folk fiddlers, Dave Swarbrick's name towers high above. "Swarb," as he's known by friends and fans alike, is renowned worldwide for his high-energy, virtuoso antics. The Coventry-based musician's whirlwind of violin, mandolin and ebullient vocals has thrilled crowds for more than five decades. His reputation for "having a good time, all the time" also precedes him.

Born in Surrey in 1941, Swarb began his career at 16, backing pianist Beryl Marriott. He went on to perform with Ewan MacColl and the Ian Campbell Folk Group before connecting with legendary singer and guitarist Martin Carthy in 1965. The duo's kinetic chemistry proved magical and they've worked together on-and-off since. Although firmly rooted in British Isles folk traditions, the two remain unafraid of exploring songs, arrangements and energies rarely considered in folk circles.

In 1969, Swarb first performed with Fairport Convention as a session musician for the group's Unhalfbricking release. Impressed by the band's open-minded attitudes and caliber of musicianship, he soon joined as a full-time member. Swarb played a key role in the group's transformation from its American pop leanings into a pioneering unit that seamlessly meshed traditional British Isles music and rock. Fairport also saw the debut of his famed electric fiddle sound that found him reinventing the instrument to match the profile and volume of the band's other plugged-in components.

With a revolving line-up featuring the likes of Sandy Denny, Ashley Hutchings, Dave Pegg, Richard Thompson, and many others, Fairport continued into the early '80s with Swarb, releasing more than a dozen albums. After briefly breaking up, the band reformed without him, although he continues performing with it during the annual Cropredy Festival reunion, as well as in occasional guest appearances.

While Swarb's Fairport activities shone the spotlight on his electric fiddle work, solo albums released during the '70s and '80s—including Swarbrick, Lift the Lid and Listen, and Smiddyburn—reminded listeners of his acoustic prowess. In fact, most of Swarb's post-Fairport pursuits have been in the unplugged realm with groups including Whippersnapper and the Band of Hope, as well as in duos with Kevin Dempsey and Simon Nicol.

Recent years have seen a deceleration in Swarb's typically busy pace. Between February and May 1999, he was hospitalized with a bronchial condition, resulting in a tracheotomy. A bemusing turn of events accompanied the ordeal. A reporter at Britain's Daily Telegraph newspaper became convinced Swarb had shuffled off this mortal coil. A lengthy obituary was published in the paper on April 29th that year. After realizing Swarb was alive and well, an apology was printed. "It's not the first time I've died in Coventry," he quipped after the incident. The black comedy of errors ended up making global headlines in Reuters, the Associated Press, CNN and countless other media outlets.

Unfortunately, Swarb had a relapse of his bronchial condition and required intensive medical care once more during March 2000. Thankfully, further obituaries didn't accompany the bout. "They are going to make sure of my demise the next time 'round," he told Innerviews.

Swarb spoke to Innerviews in his first in-depth interview in more than 20 years. "I reckon most interviews have nothing to do with a real interest in myself or the music I play," said Swarb of his disinterest in communicating with the press. "A typical interviewer would ask me 'What it's like to be in Steeleye Span?'" In contrast, Innerviews began by discussing his current projects, including recent duo releases with Australian singer-songwriter Alistair Hulett.

Dave Swarbrick, 1977 | Photo: Transatlantic Records

Dave Swarbrick, 1977 | Photo: Transatlantic Records

What are you up to at the moment?

I am playing this year with three friends. First, with Kevin Dempsey, then with Alistair Hulett, and finally with Martin Carthy. With each of these pals, I work as a duo. The difference between them musically keeps me on my toes and is very rewarding. Alistair and myself are part way through recording our next CD. Actually, I have a small home studio and we are recording it there. The trouble with that of course is that with one's own studio you don't have to worry about cost and therefore you can take years if you like to try and get it as close to what you wish it to be as possible. It's going well though and will be out at the end of this year. Kevin and I are also recording. We have some live stuff recorded that we are hoping to do something with later this year too. Beryl Marriott will be recording here too. I shall be engineering and producing her next solo CD. I've also just formed a new group featuring Kevin, Beryl and Martin Allcock which I think will be fun. On top of all that, there's Cropredy and trying to rest and pace myself. Then there is my lovely wife and two daughters. They certainly make time fly.

Tell me how the pairing with Alistair Hulett came about and why it's special for you.

In the summer of '94 I moved to Australia. I lived in the Blue Mountains and consider it a privilege to have done so. It's an extremely interesting and colorful area with a rich past. It's world famous for its wildlife and sandstone cliffs. I lived amongst parrots, cockatoos, kookaburras, snakes and lizards and loved every moment. Now and again I would leave the mountains and play a club gig or a concert somewhere or other in that vast country. One of the gigs I played was at the Governor Hindmarsh hotel in Adelaide. It sounds kind of posh, but it isn't. It's one of the better folk clubs and it's huge. After the show, I went back to the club organizer's place to give him my opinion of his wine cellar. While I was there, he played me a track of Alistair's from his then just released CD. The song is called "The Swaggies Have All Waltzed Matilda Away." I thought it a terrific song. I mentioned to Rob—the club's organizer—that I would love to work with Alistair.

After I left, Rob phoned up Alistair who later in the week phoned me up. And Bob's your uncle, here we are working together. I think he is a tremendously important writer on the scene and very likely the best too—along with Richard [Thompson]. When I was starting out in the '60s, there were a few songwriters who wrote, for want of a better title, what were then called protest songs. Now, there aren't many and I feel that's a shame. Nobody I know writes with such anger of man's inhumanity to man or of the strength of the working class except Alistair. On top of all that, Alistair uses as a vehicle for the most part music based on the tradition of the Northeast of Scotland. When I was in the Ian Campbell Folk Group, we were all steeped in that music. So, for me, working with Alistair is a chance to go back to those days and inject all I have learned in the meantime into the music.

You’ve been involved in many duos over the years. What attracts you to the format and what are its advantages over larger groups?

Yes, I have been in a lot of duos. I think that all of them have begun from a mutual desire of the two of us to make music together. There is a freedom in a duo that's hard to find in other formats. There is a huge amount of musical trust and freedom too. Most of my partners—but not all—have been guitarists. And most—but not all—have been singers. I suppose that one wants to give as broad a show as is possible. A show containing instrumentals and songs with perhaps an instrument change may reflect a great deal of variety. Some of the duos I have been involved with have been like that. But I've also been a member of a duo that has had a more specialized agenda. I'm referring of course to the work I have done with Beryl Marriott. Neither one of us sung. We simply played for a short time. I also worked with Savourna Stevenson and that was interesting. As of late, there's the stuff I've been doing with Alistair. In that duo, I am an accompanist. Then there's my work with Kevin. With Kevin, the palette is wide and full-on. He is a spectacular player. We try to stretch each other to the limit with as few rules as possible whilst trying to stay on the right side of good taste. Simon Nicol and myself were a duo for ages and that was a lot of fun as well as being very satisfying musically. Simon's a great backer of reels and jigs, and capable of adding a dimension or two. Finally, there is my work with Martin Carthy. We have been playing music together all over the world for nearly 40 years—it doesn't seem possible, but it's true.

You recently performed at Carthy’s 60th birthday concert. What goes through your mind when you think about that partnership?

What a night that was. It was the most fun I've had in a long time. It was great to see a pile of my old buddies and all at one time. Peggy ensured I had a good dressing room close to the stage. The entire cast at one time or another popped in for a laugh. It was a magical night. My wife Jill thought it the best concert she had been to. My daughters Emmie and Issy were there too, as was my sister Pat. Martin was, as usual, terrific. Everybody was on form I thought. I don't really take much notice of the years we have been playing together. We didn't do anything out of the ordinary that helped to give us longevity. We just survived for one reason or another. I am pleased that we did though. It's a pleasure to watch one's friends mellowing alongside yourself. Beliefs perhaps remain the same, but hang-ups and cares mellow with time I think.

Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick, 2011 | Photo: Topic Records

Martin Carthy and Dave Swarbrick, 2011 | Photo: Topic Records

Are you considering doing another album with Carthy?

No. Martin is very tied up with present commitments which seem to escalate by the day. And I have no desire at all to ever record for a proper company again. I feel so badly served by record labels that from now on I will only record for myself and those I trust. I wouldn't want to go into any details in case I find myself in court, but suffice it to say that I think they're all a bunch of unscrupulous, cloth-eared bastards.

All of your work comes out through your own label Atrax these days. What can you tell me about it?

Atrax isn't really a record company. It exists for me to release what I can of my stuff myself. It's a mail order company really. A businessman I am not. I don't have the sense of memory to be that. I only release my stuff and I don't sell many copies. I don't know how to really. I have no distribution. None of what I do on Atrax is in the shops. It's only available from me. I personally have contact with every single CD that leaves the house. And it's my wife's spit on the stamps.

You coordinated the production of Both Ears and the Tail, an archival Carthy/Swarbrick live CD. What are your thoughts about its release?

I think it's a fun album brimming with atmosphere and good music and a joy to have done. It was 1966 when we played the club, although sometimes it feels like it was 1066. I was pleased that I was able to release it myself and I hope that over the next few years it sells well. I enjoy producing and mucking about in the studio, so long as it's all under my control and I can pack up when I want to. The studio is next door to my bedroom at home. It's all very convenient for me. I can get up, have a bath and record a track, all without going downstairs. I am registered disabled now, so all that kind of stuff is important.

Why are you wearing mining gear in the CD booklet photo?

A-ha! A good question. Martin and I had played a folk club in Derbyshire and we were invited to go potholing the next day. We both turned up to do it, but a hundred feet or so inside the opening, Martin decided to return to the surface. I continued downwards to the very end. At the bottom of the shaft was my reward and reason for my bravery: Blue John. Blue John is a gemstone only found in Derbyshire and to this day, I wake up screaming "A pick! Someone give me a pick!" I went all that way down there and it was seriously scary with no tools to mine the stuff. I remember the helmet kept falling over my eyes which didn't help me with the dark. I also recall the contortions you had to put your body into, coupled with a ceiling height of no more than two feet. There was also the dampness and running water. I was glad to get out and when I did, Martin was there with the handshake.

Dave Swarbrick, 1966 | Photo: Elektra Records

Dave Swarbrick, 1966 | Photo: Elektra Records

Compare the '60s folk scene to how things stand today.

I can't see that things have changed much at all. Of course, when I began [in the early '60s], there weren't any clubs. Dances were the most popular evenings out if you liked folk music. Half-way through the night, there would be a break for refreshments and either a singer or a Morris side would perform. Pretty soon, clubs emerged and they're much the same as now. The songs have changed. A lot of the songs I heard then I've not heard since and the standard of playing has improved too.

Lots of youngsters are playing now and many are the sons and daughters of those early pioneers. Singers are not so good now I feel. Sure, there's one or two wonderful singers, but there were heaps of them back then. Singer-songwriters were plentiful. There's not so many now. The atmosphere has changed. Now, traditional music is accepted and for the most part, I don't think it was then. It took a long time before the music press and organizations like the M.U. [Musicians' Union] came on board. Finally, in 1966, there were a lot more clubs than there are now. A few of them were enormous. Nowadays, this is more than made up for with the advent of art centers. There's more professional performers now, and though I am reluctant to swear so, I think there's probably more gigs too.

Are you surprised by the renaissance of interest in people like Carthy and Bert Jansch?

No, not at all. I have been close to the career of Martin and been surprised that he wasn't better known. Even among musicians, he has been strangely unknown. Happily, those days are over. Nobody deserves recognition more. He has traipsed 'round the country dispensing his own brand of folk for many moons. He's also a wonderful musician and a compelling singer. As for Bert, he is another example of a unique musician who warrants, in my opinion, mass recognition. He swings like the proverbial clappers. They both do.

Do you feel you’ve received your fair due in comparison?

Oh, I think so. Especially when you consider that most of the time I go out of my way to avoid the spotlight. I hardly ever give interviews and I run away from publicity and promotion as much as I can. I like to think I can play, and I like to think I have the respect of my fellow musicians. That's enough.

Describe your relationship to the violin today.

I am as smitten with the violin as I ever was. It's a truly magical instrument in every way like no other. Its range and power of expression are unique. Apart from some modernization, it remains virtually the same instrument that was in vogue over 400 years ago. It's a sobering thought for any player. The sheer magnitude of possibilities one is capable of executing leaves me wanting to start all over again. Can you imagine over the decades how many wonderful players throughout the world have spent entire lifetimes like me bewitched by the thing? I have searched all my life for that one instrument that was meant for me and me only. I haven't as yet found it. I haven't stopped looking though. I still buy violins in the hope of finding that elusive monster and consequently I always have a few to sell should anyone be interested. As for playing, I was for a time unable to play and I didn't think I was going to be able to play again. Thankfully, that wasn't the case. The experience has left me wanting to improve my technique, to record more and to play, play, play.

What are your priorities and philosophies as a musician at present?

My priorities are as ever to work at improving my style and to hone it down so the most can be obtained from the least effort. The most meaning the fattest sound and the most accessible runs, trills etcetera. The least effort meaning trying to do that as simply and as economically as is possible—to continue to be as expressive as I can and to not hold back, as well as not going over the top either. I would like to continue to expand my repertoire and do it all with integrity and the occasional whiskey. From a personal point of view, I would like to be there for the people I love—my family and friends—and to learn to take myself less seriously. I believe that I am the most content when I am doing what I do the best to the best of my ability.

Are you still attracted to the idea of doing electric folk music?

Yes. The sheer scope and excitement of playing electric still attracts me. Mind you, that doesn't include jigs and reels etcetera. They were always more amplified than electric. The bloody horrible sound that is common with electric set-ups are not a patch on playing them acoustically. But the gadgets that you can use to enhance a song or rip a solo out are wonderful. Wah-wah—why on Earth don't more electric players use it? Octivider, chorus, delay—you can even get digital delays now almost as good as the old Copycat and Echoplex. Of course, to fully exploit all that stuff to its maximum, you also need a few other things. A good band with a powerful rhythm section and great songs help.

Have your hearing difficulties subsided enough to allow that to occur?

No, alas, probably not. I have a regime that I follow which includes seeing my specialist roughly twice a year. Provided I stick to it, I'm fine. However, that doesn't include sustained periods of electric music. Short sessions are fine so long as I take care. But I can never hang around those monitors like I used to.

Fairport Convention, 1970: Dave Pegg, Richard Thompson, Simon Nicol, Dave Mattacks, and Dave Swarbrick | Photo: Island Records

Fairport Convention, 1970: Dave Pegg, Richard Thompson, Simon Nicol, Dave Mattacks, and Dave Swarbrick | Photo: Island Records

When did your hearing difficulties first emerge and how did you deal with them?

As a child, I was constantly in pain with earaches. I saw loads of doctors. Unhappily, I never had a correct diagnosis. It transpired that I had a mastoid in my left ear, and it was recognized as such when I was in my mid-20s. I had an operation described as life-saving at the time and most of my ear was removed. Since then, I have had some seven or eight ear operations. As testimony to the adroitness of the surgeon—Mr. Groves, who was also a fiddler— the ear that had most of the workings removed is currently my good one. During my stint with Fairport, the volume affected and damaged what was left and I was advised to put down the electric fiddle and play the acoustic one. The best advice I can give musicians is to never have your ears syringed. Always have them professionally cleaned by a specialist. And remember, there is no cure for damaged ears. Seek a second opinion if you have a problem. Tinnitus is easily got and it's for life—I know.

What’s your take on what Fairport and Richard Thompson are up to these days?

I like just about everything Richard's ever done. He bestrides our scene like the colossus he is. Fairport still means the world to me. I care enormously how they are progressing and developing. I think they are just coming to terms with the current line-up. They are just beginning to exploit the chemistry. I predict that they will surprise their critics. While I am on that note, it's a shame that people insist on comparing one line-up with another. It's inevitable, but it certainly doesn't help one's confidence when you're up there to be always compared to another. I feel that the current line-up is coming into its own in a big way.

You once said you’d like to rejoin Fairport if they’d have you. How do you think your presence would enhance their current output?

That was a while ago I said that. But yes, there have been many times when I was sorry to have left. There have also been many times when I would have signed up again. The years I spent in Fairport are the happiest years I have spent on the planet. We were all each other's best pals. We were creating wonderful music. And none of us took any prisoners when it came to having a good time. A bloke would have to be unconscious not to say yes to another helping. As to what would I add to the current line-up? More of the same I suspect, plus a few more traditional songs maybe.

Fairport Convention, 1978: Dave Pegg, Dave Swarbrick, Simon Nicol, Bruce Rowland | Photo: Vertigo Records

Fairport Convention, 1978: Dave Pegg, Dave Swarbrick, Simon Nicol, Bruce Rowland | Photo: Vertigo Records

Why didn't you take part when Fairport reunited on an ongoing basis in the mid-'80s?

Well, there wasn't just one reason. There were a million reasons. I was disenchanted with the whole business of playing and had been for awhile. Also, I had just made Smiddyburn and it sold about 100 copies worldwide. Living in Scotland had turned me into a bit of a recluse too, so I dropped out.

Has the opportunity to rejoin Fairport presented itself since?

No. And given the state of my present health, it wouldn't be possible now. I was never asked if I would like to rejoin and I didn't ask to rejoin either. Sometimes it's better and wiser to just leave things as they are. I like to think, however, that yes, I have a few ideas still. We are all very compatible—musically and otherwise. Peggy and myself are brothers. His cares are mine. He is family to me.

What are your thoughts about the unofficial release of the Fairport Manor tapes?

I don't know where they fall in the Fairport oeuvre, but probably outside it. You should treat them kindly though, for without them—and incidentally Gottle O'Geer—there would probably not now be a Fairport. Gottle O'Geer, I would like to say once and for all was not ever supposed to be a Fairport album. It was to be my solo album, and I wish, along with most other people, that it had remained that way. Chris Blackwell, who to my mind is the richest, clueless, most unscrupulous pillock it was ever my misfortune to meet, had other ideas.

The Manor sessions were fraught with worry. It was a time of consolidation for Peggy and myself. We were the only members left and it was up to us to either jack it in or continue. We discussed throwing the towel in and perhaps forming a new group together. We decided to continue. Personally, I would have preferred for the tapes to have never surfaced. I get upset at the thought that one is now unable to have any control at all over one's past output—that the decision to publish is not the artist's anymore. It seems now to be up to a marauding band of well-meaning fans to make those decisions. That can't be right can it? No-one ever contacted me, Peggy or any other band member before releasing the Manor tapes. Most alarming of all, where did whoever it was that released them get them from? It disturbs me that it's possible they came from my own collection—that someone I trusted stole them. I don’t think so, but until I know for sure that they came from another source, and I can't believe that there were more than a couple of us who had copies, I do wonder.

Fairport Convention, 1974: Dave Swarbrick, Trevor Lucas, Jerry Donahue, Dave Pegg, Sandy Denny | Photo: Island Records

Fairport Convention, 1974: Dave Swarbrick, Trevor Lucas, Jerry Donahue, Dave Pegg, Sandy Denny | Photo: Island Records

What do you make of the two books released on Sandy Denny last year?

I haven't read them and don't think I will ever be able to.

How do you look back at the obituary incident two years later?

I was in hospital, out of intensive care and recovering in a general ward when it happened. I was very weak and unable to do much for myself, so when I heard Jill's voice coming from the nurses' section at 8.30 a.m., I was surprised. She was keen to tell me I was dead before anyone else did. She then read it out to me. I was unable to hold or read it myself and although my first reaction was to laugh, I soon realized how much everybody was upset. Jill went on to field questions and answer a constantly ringing telephone, as did Peggy.

The tabloid press camped outside my home and on the hospital grounds. It was, I must say, an absolute nightmare from start to finish for Jill as you can imagine. I told the hospital administration that I didn't wish to speak to the press and tried to let it blow itself out. It was a good review though—flattering. To tell you the truth, a bit of a relief too in that it only contained what seemed like good bits. I get a funny feeling reading it though and can recommend the experience to constipation sufferers. Now, I look back on the whole thing with affection. My attitude hasn't actually changed much. I still find it funny. I am pleased that someone would say nice things about me when I die. I am pleased I was able to read them. Incidentally, I have been selling copies of it at gigs, but The Daily Telegraph warned me not to continue to on the grounds of copyright infringement. Now, that's chutzpah.

Did you ever determine how that incident occurred?

No, I didn't inquire. The Daily Telegraph didn't give me an explanation either. A very meager apology was printed in the paper the next day and Jill received a similar apology from their legal department. I did think of suing, but it was such a good obituary that my lawyer thought it could be argued that it had actually furthered my career. At the time, I didn't care that much as I was ill. Now, I would like to read the next one and see what they say. It's unlikely that I will I suppose. They are going to make sure of my demise the next time 'round.

Dave Swarbrick, 1977 | Photo: Transatlantic Records

Dave Swarbrick, 1977 | Photo: Transatlantic Records

What do you think about the irony involved in that it resulted in the most media coverage you’ve received in decades?

Yes, it was the most press I've had for years, but really, I don't give a toss. It's all so silly, don't you think? None of all that cobblers has got anything to do with music. In the old days, the record company would employ a publicist and he or she would spend their time trying to get you in the papers. You can see the reasoning I suppose—the more the public knows your name, the more likely they are to buy your records. I thought then, and still do, that that's bollocks. However, we all like unusual stories and the tabloids exist on them. My story was not only unusual, but it was made delicious for them. They all hate The Daily Telegraph and by printing the story, they were having a go at them as well. But like I say, none of it really matters.

Did the incident make you reflect on your own mortality?

No, I don't think it did. I had already spent quite enough time thinking about my mortality and I had somehow moved on. It was funny and educational. I had wondered if I would get an obit and now I know—a good one too. But it didn't provoke any particularly deep musings on my part. I had been ill for a while and crossed that bridge already.

My understanding is you’re still suffering from a bronchial condition. Describe what you’ve been going through and how you're doing overall.

I was sedated for two lengthy periods on a cocktail of morphine and other substances. I emerged with what is called "intensive care psychosis." I am still trying to understand all of that. Suffice it to say, that my lungs collapsed and that I have what is now fashionably called "C.O.P.D." In fact, it's emphysema. I have had two lengthy spells in hospital. With each, I had a tracheotomy. Now, I need oxygen most of the time. But then we all do.

Dave Swarbrick, 1969 | Photo: Island Records

Dave Swarbrick, 1969 | Photo: Island Records

The rumor is you still enjoy a pint and a fag despite your condition.

That's wrong I am afraid to say. It would be wonderfully carefree and frivolous too if that was the case. But I want to live as long as I possibly can. I have many reasons not to give up yet. It is a fact that one ciggy could kill me. Believe me when I say it's easy to give up under those circumstances. Sadly, I can't drink beer anymore, but copious amounts of wine and the odd vat of whiskey do not seem to be beyond my capabilities.

You’re well known for your wit. How important is it to have a sense of humor in this business?

It used to be said that criminals and musicians were the funniest people. In my experience, having known both, that's true. I think that if you're in a line of work that is full of disappointments—breaks that never happened, checks that didn't arrive—it's a good defense. Most of the musicians I know are funny. I had the pleasure some 30 years ago of meeting Spike Milligan. In the course of conversation, I congratulated him on "Puckoon." He replied that the only people to have congratulated him were musicians. I think that wit is important. I laugh a lot. I am flattered that I have a reputation such as you mention.

Is it true you were once fined by Transatlantic Records for performing your own music without their permission?

Yes, it's true. I was fined by Nat Joseph [founder of Transatlantic] for playing on Martin Carthy's first album without his permission. I suppose he wanted a credit on Martin's album—"Dave Swarbrick appears by kind permission of etcetera." Perhaps he got it. I'm not sure. Amazing isn't it? And you ask if it's necessary to have a sense of humor?