Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

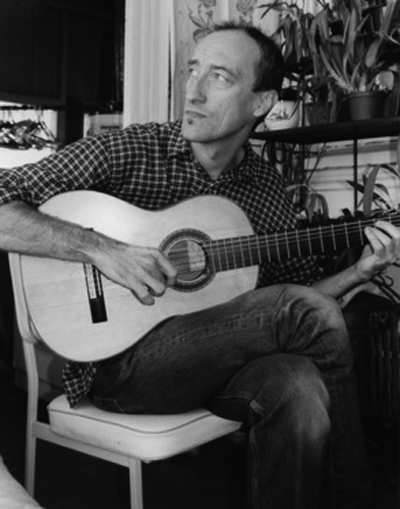

Miroslav Tadic

The Heart of the Instrument

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2003 Anil Prasad.

For the better part of the last 20 years, guitarist Miroslav Tadic has quietly influenced musicians worldwide, both through his prowess on his instrument and his role as a champion of Macedonian music.

Renowned by critics, musicians and listeners alike, Tadic situates his virtuoso acoustic and electric guitar talents within a variety of intriguing contexts. Traditional Eastern European music, North Indian classical music, jazz, rock and avant-garde influences are just a few of the realms his improvisation-based approach taps into. But it’s the music of Macedonia that’s closest to his heart. Many of his most notable recordings, including his latest release Lulka, explore that country’s musical traditions, both in their original form and infused with sounds from around the world.

Tadic, 44, departed his native Serbia in 1979 for the United States in a quest to take his musicianship to the next level. At the time, Serbia didn’t have much in the way of formal guitar training, so he took up an opportunity to attend CalArts, a prestigious Los Angeles-based music school. Tadic eventually chose to relocate to the area and now teaches at the school when he’s not recording or performing.

Apart from his solo recording and teaching careers, Tadic is in demand for sessions and performances by luminaries including Jack Bruce, Terry Riley, David Torn, Joachim Kuhn, L. Shankar and Markus Stockhausen. However, his most notable and enduring collaboration is with percussionist Mark Nauseef. The pair have worked together since 1986 on more than a dozen albums and are routinely mentioned in the same breath.

Innerviews began its conversation with Tadic by exploring his fascination with Macedonian music and his recent work with two of the country’s biggest stars: guitarist Vlatko Stafanovski and vocalist Vanja Lazarova.

Let’s start by going through the basics of traditional Macedonian music and why it appeals to you.

We should situate Macedonia first. Geographically, Macedonia is in South-Eastern Europe, right before you get to the Near East. It borders on the West with Albania, on the north with Serbia and Yugoslavia, on the south with Greece, and on the east with Bulgaria. It’s a place that any people who were moving from east to west, either in a peaceful way or an aggressive way would encounter — for instance, if the Ottoman Empire was moving toward Spain or to the West trying to take land, Macedonia is always in the way. It’s always at the crossroads. So, strategically speaking, Macedonia is a very important place and that’s why a lot of empires wanted to have it as part of their territory. That’s why, even today sadly, it’s in the news.

What Macedonia’s geographical location means for music and culture is that many musics are considered indigenous, local music. It’s a real melting pot of centuries of various kinds of musical and cultural fusion. So, you first have all of the local music, which is basically very calm, simple and diatonic. They have several specific instruments particular to the area. One of them is called a kaval, which is a diagonal flute. They also use bagpipes and a big drum called a tapan that’s played with a heavy stick on one side and a thin stick on the other. This instrument also appears in Bulgaria, Turkey and India.

Then you have the very heavy influence of the Ottoman Empire, which had highly developed classical music within what’s called the Maqam system — a modal system, not a harmonic system. Then there’s Turkish folk music and the really important influence of the gypsies who traveled from the south of India and then moved to the west. The gypsies were nomadic people and they would stay in certain places and then move on and on. They’re musical and artistic people and they would pick up many influences along the way because they would try to integrate somewhat into whatever scene they were in at any given time. They would learn the local music and put their own twist on it. There was a lot of ornamentation and they included a lot of the metric stuff that comes more from India and Turkey.

When you add it up, Macedonian music has several polarities. One of them is it has really beautiful, melancholy roots that are in free time, that usual relate to the mountain life which are played by shepherds in the mountain and are then brought into a concert situation with compositions. Macedonian music also has odd meters that are very common to the area. For example, most popular songs are written in seven beats. Seven, nine and 11 are other common meters.

Melodically, if the music comes more from the instruments of the Turks and gypsies, that means it will have more exotic scales that are associated with the Middle East. If the melody originates locally, then it will sometimes be pentatonic or have a simpler diatonic melody, but like a lot of folk music, it is very simple, but very beautiful and special. If you take one of those simple tunes and play it, it feels perfect. But if I try to write something like it, I’ll never be able to really nail it completely because there’s a characteristic of the folk music that’s very simple, but very specific.

So, all of those factors attracted me to Macedonian music. When I lived in Yugoslavia, I lived in Serbia, which is north of Macedonia. The local folk music in Serbia is somewhat different. But all of my friends and I who were musicians were attracted to Macedonian music because it has this incredible vibrancy, colored by all of these various influences.

Why weren’t you as enamored by Serbian folk music?

Basically, Serbian folk music is very regionalized. Serbia is not a very large state, but it’s larger than Macedonia, so you have very different kinds of music there. I didn’t find the music very adaptable to the guitar and it was more monotonous and wasn’t as interesting to me. It’s usually in 2/4 with very simple tunes. But even though it wasn’t interesting to me as a player, it was interesting to me as a listener because it associates two different parts of the country and different times of my life. It just didn’t have the musical elements that I felt I could work with and develop as a musician. There are certain parts of Serbia where the music is very similar to Macedonian music — particularly the further south you go. So, there is similarity, but the particular characteristics of Macedonian music were more interesting for me to work with. It’s a little more complex and richer in terms of the combination of influences.

Describe your journey from Serbia to Los Angeles and how it led you to developing a significant interest in Macedonian music.

I left Yugoslavia when I was 19. I was just beginning to develop as a musician. I really didn’t pay much attention to folk music then. As a teenager, you’re not going to listen to the stuff they’re doing up in the hills. I was getting into jazz, people like Coltrane, and I was still listening to things like King Crimson and Yes. I was always into Hendrix too and all of that was much more what I was interested in while I was there.

I went to CalArts in 1979 and I teach there now. I took classical guitar. The reason I left Yugoslavia was because at that time, guitar wasn’t an instrument you could study at a conservatory in many countries. It was accepted late as a serious instrument. I had a chance to come to CalArts and it was a dream school. I got a catalog and I was sitting in Yugoslavia thinking “God, I’ll never get into this place.” Then I sent them a tape and they accepted me and I came over and figured out how to deal, basically.

When I came to the States, I started realizing when I got some distance, how interesting Macedonian music is. It’s sort of like you need to leave the place to realize there are a lot of good things about it. One of the good things about leaving for me was to realize that this music was there and somehow provided me with a connection to my identity as a person. In fact, it developed to the point where it is now closely tied to my identity as a musician. So, I went back very often and collected recordings and brought them back to the States. While I was a student, I started incorporating Macedonian music into my recitals and teaching it to some of my friends — usually American musicians — and it became a part of my regular vocabulary.

The group Bracha represented your first major step into fusing Macedonian music with other influences. What can you tell me about that experience?

I’ve had various phases with Macedonian music. When I was a student, I put together a band that would play it in an authentic way. I was into the idea of being able to play this music alongside American musicians with their ornamentation and odd meters. They always did really well. So, that was the initial phase, but I wanted to take the music in a direction where it would just be an influence, rather than me specifically playing that music. So, after that phase, I started Bracha. That group was originally a quartet with Dave Philipson on Bansuri, John Bergamo and Mark Nauseef on percussion, and I played classical guitar.

Bracha was the first time we started taking Macedonian music into another direction. We played our versions of these tunes and opened them up by changing certain things. It was a great band. David would bring in the Indian influence when he improvised and we had incredible percussion happening between Mark and John. They added all kinds of interesting meters and rhythms — things that would never be found in the actual folk music. So, Bracha was a doorway into dealing with this music in various, non-traditional ways.

It’s important to note that my thing is always keeping a real connection with the essence of the music and having the utmost respect for it. I wouldn’t take it in a direction I would consider inappropriate. This doesn’t have to do with the authenticity of the music, but with my own relationship to it. My version should still retain the original quality that attracted me to the music in the first place — a certain simplicity and purity.

After Bracha, you became interested in taking a more electric approach to Macedonian music.

Yes, because a lot of it is loud and powerful and I thought the sound of a rock band would be appropriate for this music. As a matter of fact, they divide folk music in various ways. One of the ways is dividing it into indoor and outdoor music. There is music specifically designed for the outdoors for important events such as weddings and funerals — which are usually the biggest social and musical events of the year in the villages. This music is played on loud instruments like the zurla — a very loud instrument similar to the shenai in India. It’s sort of like an oboe with a really nasal sound. It’s just unbelievably loud. You can’t be in a room with it. So, at an outdoor event, you’ll have two of those and a big drum. In recent times, they have brass bands which are all military brass instruments like tuba, euphonium, several kinds of trumpets and a big military drum. It’s very funny music — they’ll just play for hours, because at a wedding, you have to just keep going. The band must not stop, so you have tunes that are one hour long. The sound of this kind of music is very similar to the raw, powerful sound of a rock band like the Ramones. [laughs]

So, what I did after Bracha was start a group called Slavster. It was a quintet with two guitars, bass, drums and saxophone. Peter Epstein played saxophone in the band and I still work with him. He developed an incredible understanding of the music, ornamentation and so on. At the same time, he’s an incredible player with serious roots in jazz with both Coltrane and post-Coltrane stuff. It was great to play with him and we had a very strong following in Los Angeles. We were about to get a record deal, but the record label got sold and they wanted to do a completely different thing, so the project fell through. In the meantime, the guys in the band wanted to move on to something new, so the group basically dissolved before the recording.

After that, I started another quartet called Son of Slavster featuring drums, bass, guitar and electric violin. This band essentially started with me working with students at CalArts who developed to such a high level as musicians that I felt totally comfortable considering it a professional band. The group had a serious following in Los Angeles, where we played regularly. What happened with the violin player is a funny thing. His name is Anand Bennett and he’s half-Indian. His mother is Geetha Ramanathan Bennett, who is one of the greatest South Indian veena players. His dad is Frank Bennett, who is a great composer and drummer, so he’s been surrounded by music as a kid. He’s a super-talented and accomplished player, but at a certain point, he developed a real block about playing violin. All of a sudden, he didn’t want to do it anymore. He wanted to switch to electric mandolin and he still plays that instrument now. But I didn’t feel electric mandolin was the right instrument for the band. The whole sound of the group was dependent on the combination of electric guitar and violin. Mandolin was another plucked instrument. So, I had to dissolve that band and everybody was bummed out, including Anand, who really loved that music. But I understand his decision. Anand is a great player and today plays a weird mandolin instrument and contrabass.

Another notable Macedonia-related collaboration of yours is with Vlatko Stafanovski.

Yes, he’s a very well-known Macedonian guitarist in the former Yugoslavia and Macedonia. He’s a very fine player who primarily plays electric guitar. We met and really hit it off well. We knew a lot of the same tunes and had similar ideas about how to do them. He agreed to do an acoustic record with me and over an extremely short period of time, he developed amazing technique and approaches on nylon string guitar. We play in two completely different ways. He plays with a pick, John McLaughlin-style and I play with my fingers using classical and flamenco techniques. Between the two of us, it’s a very nice collaboration with each of us making a different contribution. We decided to make a whole record of traditional tunes, songs and dances on two acoustic guitars called Krushevo and it’s been very successful.

Vlatko, being very highly recognized and respected in the former Yugoslavia, sort of introduced me to my own people in a way. We usually play to anywhere from 1,000 to 5,000 people over there, which is amazing. The crowds are always very quiet and respectful when you’re playing. The region had some really dark years over there, but now people are coming to concerts like in any European city. They really consider these shows something. Several television stations said our concerts were the musical events of the year.

We’ve recorded two albums together. The latest is Live in Belgrade which was recorded when we played the biggest hall in Yugoslavia. It was packed with 4,500 people. It’s pretty amazing considering it’s two acoustic guitars. There are several new pieces on the record, but it’s pretty much the same music as Krushevo live. It has a different kind of energy and the material has matured with us. It’s a different take on that music.

Obviously, guitar is now fully accepted in the region.

In terms of being able to study guitar at a conservatory, that’s been in place for many, many years. Now, it’s a popular instrument just like anywhere else. It’s also one of the most highly-accepted instruments. But the project with Vlatko and I is a refreshing one for people. It’s the sound of two acoustic instruments that communicate a lot of power. I think that’s what people are responding to — the fact that there’s no big light show or anyone running around. But the music still transports you in a certain way. I’ve really enjoyed playing with Vlatko and receiving this kind of attention and respect, which is very genuine.

How well have the records with Stefanovski sold?

In those territories, if you sell 5,000 to 10,000 copies, that’s really good. Live in Belgrade is the only record that’s been put out with our control. It was released by a Macedonian company and I have the exact numbers in terms of what’s sold, unlike any other record company I’ve recorded for. My experiences speak in favor of putting out your own music. I’m tired of getting no statements for what I’ve done or getting statements that are obviously ludicrously false. Live in Belgrade is a record that we recorded, edited and produced ourselves. It’s the first record for which I get paid for every record sold for exactly the amount of money that was agreed on. With most record companies, you have to go after them to get money from them. Most of them don’t do what they’re supposed to do, which is send you a statement and a check.

It doesn’t have to do with the music industry in Macedonia. It has to do with particular people. Integrity is about people, not territories. Depending on what label you’re working with, you’re going to get a certain personal or business relationship that’s right or wrong. I’ve been involved with record companies who are forward looking and that’s a good thing, but I haven’t been able to make a living from that, which is a strange thing to say for someone that’s recorded 15 CDs and received great critical acclaim. What I get are $34 or $10 checks here and there — checks so small, I don’t cash them. So, something’s wrong somewhere. I support myself partially from teaching, otherwise I’d be in court a lot.

What’s special about the musical chemistry you share with Stafanovski?

What’s unique is that as musicians, we don’t have a lot of common reference points, except the guitar. He’s a virtuoso electric guitar player and songwriter. He had a band called Leb i sol, which was one of the most important Yugoslavian bands in history. The group influenced several generations of people. The group is the region’s equivalent of the Ramones or Bruce Springsteen in America. People know the songs of his band and connect part of their lives to them. Vlatko is a really first-class instrumentalist as well. As his main instrument is electric guitar, he plays with a pick, using regular guitar technique. I’m a classically-trained player and I use classical and flamenco influences in my playing. When he switched to nylon string guitar in order for us to work together, he chose to play in the same way that he approaches electric guitar. So, you have the classical and flamenco elements from me and McLaughlin-like virtuosic single-line playing from him that incorporates his rock and blues way of thinking. My thinking is oriented towards making textures, harmonies and bass lines that offer the rhythmic elements of flamenco and the harmonic elements of jazz and Brazilian music. When you add it up, we cover a wide spectrum.

We also get along really well as people. We’ve spent a lot of time together. I know his whole family. In addition, everything we’ve done has been on a high level and very clearly defined in terms of business dealings. So, it’s a perfect musical and personal relationship. We enjoy each other’s company and have a really good time when we’re out on the road.

Your latest release is Lulka featuring Vanja Lazarova, one of Macedonia’s greatest, living exponents of traditional song. Tell me about that collaboration.

Vanja Lazarova is about 75 and she’s in really good singing shape. She’s pretty much the only person that still does the older style of singing with the ornaments and everything. She’s really amazing.

Macedonia is an area close to Bulgaria and Greece, so the music is basically Balkan. That’s the tradition that has influences from Turkish to Middle Eastern music. It has ancient connections to old Greek music and Byzantine music too. She’s one of the people who comes from generations who have learned just by doing it. It’s sort of an oral tradition. She’s someone like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan that came from a whole lineage of people who have been singing, developing and preserving that music. It’s folk music that has the same subject matter as most folk music. There are lots of love songs, songs that have to do with the passing of time and passing of youth. And because a lot of the time people left the area to go elsewhere to work in a foreign land, some of the more depressing songs deal with that.

I sort of developed my whole approach to Macedonian music partially by listening to a lot of old recordings. Some of those old recordings were actually by her. We were put in touch with each other and experimented together on one piece and she really liked it. Then a record company in Macedonia called Third Ear Music got really interested in doing the whole project. So, I went to Macedonia and we recorded a dozen tunes with just acoustic guitar and her voice. Then I brought the stuff to L.A. and did a number on them. [laughs] I had a couple of guests, an Iranian musician who’s playing some traditional instruments and a DJ I’ve been working with. We’ve done what I think are really interesting, unusual takes on that music. There’s some drum programming, but it’s very organic and quite different from the types of treatment that music has received elsewhere.

Some of the stuff has just one guitar with her vocal and other things have interesting African influences, stuff coming out of Thomas Mapfumo, and I have my own thing with some simple acoustic sounds. Some things have more ambitious production elements too. It’s a bunch of different angles. Each tune is a little story in itself.

What does it mean for you to take your version of Macedonian music back to Macedonia and have it appreciated there?

It’s an unbelievable thing. It’s very moving. I once took a cab to Vlatko’s place in Macedonia. When I stopped the cab and walked in, the guy says “You’re Miroslav Tadic.” It’s like wow, man. I’m not from very far away, but I wasn’t born there. They really appreciate what I’ve done to their music and the dedication I have to it. It’s an incredible, wonderful feeling. I have had the opportunity to meet some of the great, old, traditional singers who also know who I am. For me, this is like meeting Coltrane or Hendrix. I’ve spent years listening to their records. Ultimately, if I can take a different approach to their music and bring it back to them and have them accept it, it means I’ve done something well.

What’s your perspective on the recent, tragic history of the former Yugoslavian countries?

It’s a very sad thing. It wasn’t a situation I wanted to witness first-hand. My parents used to tell me “I’m glad you’re not here.” It was a sad thing to hear. There were a lot of Yugoslavian people who felt they wanted to go back and do something, but the whole thing was so evil and there wasn’t really a good side you could actually be on. Basically, it was people being manipulated very badly into these horrors that happened. Having left at 19, I didn’t have the same kind of ties to the place itself as some of my friends who left when they were older. But I was tied to my family and really concerned about them. It was very depressing, but things are normalizing now.

One thing about my work with Vlatko is we play instrumental music and he is recognized throughout all of the former Yugoslavia. We are some of the first musicians who have actually played everywhere in parts of the former Yugoslavia. Typically, if you’re a Serbian musician, you can’t play Croatia, because there are too many things tied to the fact of where you’re from. Our music transcends that and I’m very happy about it. In a certain way, we are some of the first artists contributing to putting the thing back together — bringing people back to the roots of who they really are and getting rid of that national identity bullshit that’s just a tool for manipulation. If you play music everyone can relate to from our part of the world, you’re doing much better than going out there and singing songs about wars or against wars.

I don’t believe we can go out there and create instant changes of political opinions in millions of people. But if we’re playing for 1,000 people and a few people are touched by the music in a way that helps them realize that some things are beneath them and that they shouldn’t go down to that level, I’m very pleased. The most important thing is a feeling of humanity — feeling that you’re a human being. If you feel that other people are also human beings, then you’re looking beyond the ideas of nations, race and religions. I feel music operates at that level — beyond all of those divisions that are pretty much artificial. If I’m born in Serbia, I’m a Serb and someone else is a Croat. Did I choose to be one over the other? No. It’s a random thing that you belong to some nation. Your value has to be with who you are as a human being.

How did you first meet Mark Nauseef?

I met Mark at CalArts in 1986. He came to CalArts because he wanted to study with several particular people. He was already very well known and had a serious career going on, but he doesn’t like the status quo and being in a rut. Mark basically suspended his career at that time, which is amazing because he was doing solo records, he was in Jack Bruce’s band and was working all the time on a lot of projects. But he was really interested in expanding his knowledge. So, that’s how our friendship and partnership began.

In particular, Mark wanted to work with Pandit Taranath Rao, a great tabla master; Pak Chokro, the greatest living Indonesian musician who was teaching Javanese music; and the Ladzekpo Brothers, who were teachers of traditional music from Ghana. Mark was really interested in getting as deep as possible into these areas that were outside the regular drumset playing within jazz and rock.

When he first arrived, we didn’t really communicate much. We met during his first year, but I didn’t know much about what he did and he didn’t know what I did, though we had several occasions to play together. I distinctly remember one time when Mark and I were playing with John Bergamo and David Philipson in the group that was to become Bracha. There was a particular rehearsal where we realized there was something really happening. That’s when Mark decided to seriously pursue the group.

Someone once said they’ve never heard anybody play Macedonian music in as an original way as Mark Nauseef, yet preserve the spirit of the music. They were including Macedonian musicians when they said that. So, Mark has a really deep understanding that’s even beyond local musicians following a tradition. Eventually, Mark felt, and rightfully so, that Bracha was too percussion-heavy. You had two quiet acoustic instruments, nylon string guitar, bansuri and two percussionists. So, Mark felt it was better for it to go on as a trio.

Mark also invited me to join another band he had called Dark. I had this incredible situation. I had Bracha in which I was playing classical guitar and Dark, where I was on electric guitar. It was an incredible time for development, growth and experimentation. It was during that time that Mark and I felt we could really work together well. We got along really well as people and to this day, we’re very close friends. There is a great amount of mutual respect.

Describe your musical working relationship.

An interviewer once asked me who were some other drummers I would like to play with and my answer was “I just want to play with Mark because he’s such an incredible musician.” He’s truly beyond the instrument of drums too. He’s somebody who can really shape the music. Drums are the most powerful instrument for shaping music if you know how to do it, but most drummers can’t. If you’re playing with Mark and things start going nowhere, he’ll immediately move the music to a place where it will. He won’t just keep the groove going — he’ll make things happen.

Mark is a musician with an incredibly broad range, both expressively and dynamically. He can play a full drumset and I can play nylon string guitar, both without amplification. We can play for hours with no problem. He never gets overpowering. But he’s also the loudest drummer I’ve ever played with, if it’s necessary. He can produce unbelievable volume and still be very musical.

Together, we cover a wide range. If you just put us in a room with any instruments, even a frame drum and a mandolin, we can make music together. We don’t really think about it anymore too much. We used to rehearse a lot and play music for days — just straight music for eight hours a day for several consecutive days. We’d record, listen and talk about it forever. It’s a priceless relationship. Something just comes out of this amount of time and experience together that’s pretty intangible.

What’s the status of your partnership with Nauseef?

We performed during a nice concert in January 2002 in Germany, with Tony Oxley. It was a meeting of interesting musical minds. We don’t have any specific plans right now. Everyone is kind of doing their own thing. We’re also both growing weary of traveling lately. It’s no fun to get to the airport. Mark lives in Germany, but we’re both working on having a high level recording situation in our homes. So, when he comes to the States, we’ll be able to immediately do some recording. There was also the idea of the band with Mark, Bill Bruford, Steve Swallow and David Torn, but that became very hard because of people’s scheduling and all of the traveling. So, that idea has been shelved for now. It was something that everyone agreed on and were very enthusiastic about, but right now, it’d be hard to make happen.

Tell me about your experiences working with David Torn.

I think we complement each other very well. When I play with him, I emphasize the other side of how I play, which is much more rhythmic and pointy, as opposed to his playing, which is very fluid, melodic and sonic. I think I provide more of the rhythm, tied with Mark, to give David a situation where he can basically fly over the rhythmic process happening underneath. We get along really great. Our relationship is based on mutual respect. Also, we don’t have a lot of common ground in terms of playing, so we don’t get into a “Well, I am faster than you!” kind of thing. [laughs] There are no elements of ego. Torn is one of the greatest. It’s always been so easy to play with him. You don’t have to work anything out. It just happens naturally.

The thing about David is his progress. A lot of people rest on reliving past glories like Cloud About Mercury, but he has made so much progress, especially on What Means Solid, Traveler? and SPLaTTeRCeLL. I loved those records. That’s some serious shit.

Describe your evolution on the guitar over the last 15 years.

I make slow progress and I really enjoy that, because I feel if I was one of those people who are totally happening by the time they’re 25, I’d wonder what to do for the rest of my life. So, I feel I’m learning all the time. At the same time, I’m good enough that I feel comfortable, but I always know there’s a next step. My work has been about opening up and loosening up. With my classical training, things were pretty regimented and systematic, but I’ve always liked improvising. It’s a matter of learning about yourself and connecting with your instrument. It’s not just a matter of playing your axe. It’s more about “What do you know about yourself?” The more I learn about myself, my family and my friends, the more of that is reflected in my progress as a player.

Very early on, through classical training, I got some reasonable technique, so I’m not sitting there with a metronome, trying to push it a few notches. But although I feel comfortable, I’ve been focusing on making progress in feeling freer in improvising and trying to read the thought process wherever it’s necessary. That’s a real difficult one because when you start thinking, it interrupts the natural flow of the music. When the music is flowing naturally, you are not oblivious in terms of your mind and thinking, but you’re only thinking in moments, like when you’re about to change the guitar or a theoretical thing like “He’s in 7” or “He’s in 11.” Then you’re back and you’re gone again. When you think and construct things in your mind, that’s problematic. So, trying to get rid of that is part of my work.

Another thing I should mention is that about nine years ago, I spent some time in Spain listening to and hanging out with flamenco players. These people have such a high level of mastery of the guitar and a deep connection with it. I felt I needed to be guided into this area for awhile, because as a player of this instrument, I thought I owed it to myself. Previously, I kept away from the flamenco thing because it’s such a big area. It’s like learning bebop — you can’t just do a little bebop, you have to dive in there and stay a long time to get it. But I felt I had to deal with it, because it related to the heart of my instrument. It was an incredibly inspiring time.

I was in Madrid and I would spend part of the day in guitar shops with guitar builders. Different players would come in non-stop and there was this incredible excitement about the instrument and the music. I haven’t seen it anywhere else. It’s the kind of thing you might imagine in 1967 when Hendrix showed up in a club and played, followed by Jeff Beck, and then everyone would go hang out. So, I had a great shot at flamenco and it’s stayed with me. I’ve incorporated a lot of those techniques into my playing. I don’t tend to be a flamenco player at all, but I’ve got some of the aesthetics of sound and techniques. I’ve changed instruments and now I’m playing on a flamenco guitar, which is different from a classical guitar. It’s a brighter-sounding instrument, with a quicker response. The difference between Krushevo and Live in Belgrade is that Live in Belgrade is played on flamenco guitar, so there’s a more percussive and electrifying sound to me.

As far as electric guitar playing goes, it’s about integrating the two instruments. Electric guitar, for me, is a completely different instrument. When people ask me if I play another instrument, I say electric guitar, even when they mean saxophone or something. What I don’t have on classical guitar, I can get out of electric guitar and vice-versa. Each has an area that strictly belongs to that instrument, but there is stuff in-between. I’ve been making some good progress for a long time.

In order to get what I want out of an electric guitar, I have to build my own equipment. So, I’ve built a lot of analog processors which are really happening. A lot of people are impressed with them. Recently, I also started building guitars because I needed an electric guitar that had string spacing and a neck similar to a classical guitar and nobody makes guitars like that. I’ve been into tinkering and working with my hands and I find a lot of peace in sitting and making something. I delved into the challenging world of instrument building and I’ve surprised myself because I’ve built several good instruments that are exactly what I need. So, part of my development and evolution on electric guitar is related to the fact that I build them from scratch.

Over a period of several months, I learned woodworking machinery, hand tools and procedures. I know some of the top luthiers in Los Angeles and I hung around their shops. I was patient and I love doing it. In fact, I got results that I can’t believe. I’ve built a dozen since I started and now, I have a waiting list for people who want to buy them. I’ve also had commissions from several people and they’re very happy with the guitars.

Woodworking is really hard on your hands. When I was practicing quite a bit and working with wood everyday, my hands were being stretched to the limit, so I just made the instruments I needed. So, unless people are specifically interested in these kinds of instruments, I don’t think I’ll make them on a regular basis, but it’s a great skill to have. It’s a great feeling to be able to make an instrument that works quite well.

I understand you’re working on a new solo guitar CD.

Over the last couple of years, I’ve set up a recording situation at home. I’ve been recording occasionally and compiling the best pieces for a new solo record I’m probably going to release early next year.

In the last several years, there has been some fairly significant interest in my music in classical guitar circles. This is interesting for me, because although I was educated in that area, it doesn’t represent the sort of players I was after in terms of people playing my music. But because I play music using classical technique on classical guitar, some of those people have heard my records, particularly Window Mirror. The Los Angeles Guitar Quartet even recorded “WalkDance” from that record. They became interested in my stuff as repertoire for classical guitar.

For awhile, I would tell these players that there’s a lot of improvisation involved and that it’s not something I sit down and play the same way each time. Since most classical guitar players are not trained in improvisation, it’s kind of useless for them to even try and deal with that stuff. A guy called Scott Tennant came along — a member of the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet — and he really pushed me to write some of this stuff out. So, I actually sat down and did that. Instead of leaving an area open to improvisation, I wrote out what I would consider to be one of my really good improvisations. So, I published several of these pieces and now there are people out there playing my music note-for-note. So, even though I prefer to play with other musicians because I enjoy the interaction and exchange of ideas, I decided to develop more solo repertoire and perform solo in concert. The CD will feature my own compositions and primarily the material based on folk music from the old country.

Is there a spiritual element in what you do?

The spiritual element cannot be defined in any tangible way. It’s not part of a conscious religious or meditative process or technique. However, if I’m working with wood or building guitars, there are moments of spiritual highs in a sense. They’re available to us in our lives regardless of what we do. You can reach that state if you’re cutting up vegetables or cooking a meal. Music is more likely a vehicle to it, because it has a special sort of slant to it. It’s not a systematic thing, but I recognize it when it happens. I don’t strive for it, because you can’t. I just enjoy being there when it happens.

You’ve been teaching at CalArts since 1985. Tell me about your role there.

I teach people who are guitarists that are looking for their own path on the instrument. We have a very strong guitar program. And having a strong background in classical music, a lot of classical students study with me. It’s mainly composers who play guitar. They are interested in the technical aspect of guitar playing and in composition as well. I also get people who are electric players who are interested in learning a classical technique and applying it to their instrument. It’s very exciting for me because every student is different. I don’t have the opportunity to provide a particular program everyone follows. I work with each student and determine who they are, what they need and what I can do for them. It’s just like any other creative endeavor for me.

How much does economic necessity influence your ongoing career as an educator?

Economics is a part of it. Ultimately, if I had my way, I would only play and do it only when I want and with whom I want. But I can’t live from that. But to say that I’m teaching just for economic reasons would be very wrong, because I enjoy it a lot. I’m blessed because one thing it gives me is the opportunity to turn down any work I don’t want to do. It means I don’t have to take a gig playing background music at some party even if they offer me $300 an hour. I can use the money, but I don’t need it. My bills are paid at the basic level. The job gives me economic stability and provides a way to keep my musical integrity intact. Also, I’m surrounded by wonderful students and teachers. Running into people like Charlie Haden in the hallway is also totally cool. In addition, I have a handful of students I’m really proud of. I’ve played a part in their development and am thrilled with what they’ve accomplished. I’m pleased there are people who enjoy listening to their work. I go out to see them play and they send me their CDs. It makes me feel good.

What are some of the key philosophies you impart on your students?

There’s one thing in particular that’s important for me to communicate to my students. It’s musical, but has broader implications. Often, during their last year or next-to-last year, they start thinking “How am I gonna make a living? What am I gonna do when I get out of here? Should I learn more styles? Maybe my reading isn’t good enough.” In other words, basic questions of existence. I tell them the most important thing to do right now is learn as much as you can about your instrument and about who you are, as well as who you are as a musician and what you do best.

The music you love, whatever it is, is the music that’s gonna make you the most money of anything you do. Why? Because anything you love is something you’re going to do really well. And anything you do really well is something people will pay you for. Of course, you can do something else, but then you might as well be a clerk in a bank or something. I think it’s a bigger drag to be a musician playing music you don’t like than to have a day job so you can play the music you like. Look at Kafka. The guy was a clerk at an insurance company and he wrote in his free time. He wasn’t trying to get published. He was a pretty dark character anyway, so maybe that’s not the best example. [laughs] Probably better to look at David Torn. He’s putting kids through college, but he does what he does — what he’s always loved to do.

I don’t consider myself particularly talented. I just do what I want to do and hopefully make some good choices. I’ve also had some luck, but everybody can count on a little bit of luck I hope. So, again, the broad philosophy is finding out who you are, what you really want and going for it. Sometimes people are afraid of doing things they really love because they feel it’s too obscure, but it’s that which will get you somewhere.