Tangerine Dream

Sculpting Sound

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2009 Anil Prasad.

Tangerine Dream’s pioneering electronic soundscapes have inspired generations of musicians to abandon conventional musical precepts in favor of new and original modes of expression. Founded in 1967 by keyboardist, guitarist and composer Edgar Froese, the German group has served as a key innovator in both the compositional and technological realms. The band was one of the first to incorporate synthesizers and sequencers into its work that often focuses on lengthy, expansive and adventurous pieces. Whether its compositions are ambient or brimming with pulsing and propulsive rhythms, the group’s sonic signatures are instantly identifiable.

The band has wielded tremendous influence on multiple fronts. Its '70s output played a paramount role in spurring countless rock, pop and avant-garde groups to use synthesizers and electronics in their music. During the late '70s and throughout the '80s, Tangerine Dream also became a potent force in the soundtrack world, having created scores for high-profile films including Risky Business, Legend, Firestarter, and Sorcerer. The critical and commercial success of its scores is largely responsible for the acceptance of film soundtracks created entirely in the electronic domain. The '90s and beyond saw the group taking on an additional role as elder statesmen of electronica. It’s rare to find an artist from the techno, trip-hop or rave scene that doesn’t owe the act a debt of gratitude for laying the groundwork those movements were built upon.

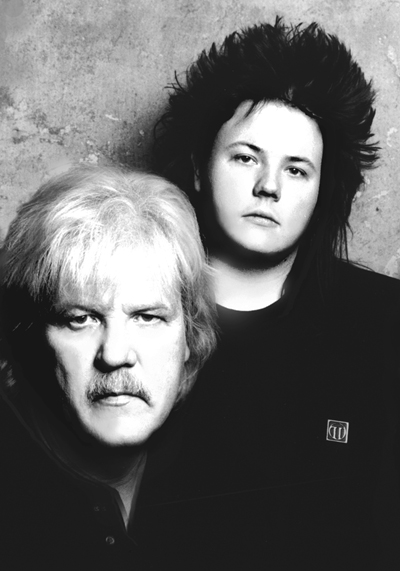

There’s been some cross-pollination too. Modern electronica elements have found their way into recent Tangerine Dream releases, mostly due to the input of Froese’s son Jerome, who was part of the group from 1990 to 2006. The band even saw fit to issue a series of CDs called Dream Mixes helmed by the younger Froese, featuring club-oriented interpretations of Tangerine Dream classics. Prior to the group’s 16-year run with a father-son focus, the elder Froese worked with more than a dozen collaborators in previous incarnations, including Christopher Franke, Paul Haslinger, Johannes Schmoelling, and Klaus Schulze, all of whom went on to forge successful solo careers.

Even with dozens of albums and hundreds of compositions behind him, Edgar Froese is not content to rest on his laurels. Between 2000 and 2006, Tangerine Dream created an ambitious three-part musical suite based on The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. Written just prior to Dante’s death in 1321, the trilogy remains one of the great classics of European literature. It explores the progress of the individual soul toward God, as well as the political and social machinations human beings engage in as they attempt to foster peace on Earth. Froese’s fascination with the work stems from his long-standing interest in spiritual traditions and the belief that like Dante’s writing, Tangerine Dream’s music can play a role in helping people come to terms with what lies beyond this sphere of existence.

Tangerine Dream also entered deep conceptual territory when exploring the 1945 World War II atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in its Five Atomic Seasons series, released between 2007 and 2009. Comprised of five distinct compositions, the recordings chronicle the tragic events as seen through the eyes of a survivor who lived through the ordeal. Inspired by a true story, the group sought to capture the emotions involved in the lead-up to the bombings, the moment of impact, as well as the aftermath.

Froese offered his perspectives on the Dante trilogy and Five Atomic Seasons, and the core philosophies that continue to inform the group’s prolific output.

Tell me about your interest in The Divine Comedy and why it inspired you to create a three-part musical epic.

Every human being during his or her lifetime asks himself or herself “Where do we come from? Where do we go?” and “What is life all about?” The answers have nothing to do with stupid esoteric behaviors or fashionable movements within esoteric scenes. Rather, it’s a very deep thing. We’ve learned that Dante, Shakespeare and Goethe all touched an area in which you can find some answers to those sorts of questions. Specifically, Dante inspired us very much. If you look at Inferno, the first part of the trilogy, you can see that it is about the situation humankind is in right now. The planet Earth itself is Inferno. Purgatorio, the second part, is the movement out of that struggle. Paradiso, the third part, is about a level of consciousness human beings can reach after certain levels of development.

To get close to what Dante was talking about, we had to consider quite carefully what we did and how we did it. There were two ways to approach it. The first is the way composers like Franz Liszt did. He composed pieces about Inferno and Purgatorio that were very dramatic and orchestrated as everyone expected. His Inferno definitely sounded like what you’d typically associate Hell with in terms of crashing sounds and dissonance. We decided to go in the opposite direction. If human beings are trapped in the most unimaginable pain and face a disastrous situation in life, at a subconscious level, those people need some sort of support. Therefore, our music generally doesn’t reflect a horrifying situation. The exception is Purgatorio in which we’ve chosen some really up-tempo pieces with a lot of sequencer stuff. It depicts how you have to step through different levels, circuits and cycles to enter into your own development of consciousness. So the music reflects that. The aim is to move people and go beyond it being just another piece of entertainment.

You use vocalists with a level of sophistication on The Divine Comedy releases that we haven’t heard from Tangerine Dream previously.

That’s true. It wasn’t easy to integrate the vocals into the work because we don’t have a great deal of experience working with voices like most other bands do. It was quite a new area for us. We wanted to integrate the pure element of the voice into the music. We used the voice as an instrument and the lyrics as a way of transporting a deeper meaning to the listener. We used different languages in order to point out that humankind has to understand that the goal of life is universal and cosmopolitan. Using all of those languages was a way of pointing in that direction. Also, we only used female voices because women are much closer to the subconscious and spiritual levels we wanted to reach. Female consciousness is completely different from male consciousness. A male tends to be more direct and always knows what to do—at least he thinks he does. [laughs] A female works from a much deeper level of consciousness. When we spoke to the women participating in the project about the lyrical structure and the deeper meaning of the entire book, they all came up with a lot of ideas that fit perfectly into what we wanted to say.

Madcap’s Flaming Duty, Tangerine Dream’s 2007 tribute to Syd Barrett, also saw you working within the vocal realm.

Tangerine Dream loves to engage in surprise activities. So we stepped off the instrumental bandwagon and engaged a singer again because we felt like it was another excellent opportunity to combine words and music. For this album, we found some very old and timeless poems by people such as William Blake, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman that we used as lyrics. The criteria was that they should feel as wise and surreal as the music of Tangerine Dream and Pink Floyd. I confess that The Floyd and Syd Barrett were major influences on Tangerine Dream’s work. I feel that both bands came more or less from the same background.

Describe how the opportunity to create the Five Atomic Seasons came about.

Tangerine Dream got the offer from an 82-year-old Japanese business manager named Mr. H.T. in November 2006. He wanted us to compose and record the so-called Five Atomic Seasons series. It was clear that this was a really serious assignment. Tangerine Dream was told the person who ordered the compositions studied during his youth in the two cities that were destroyed by atomic bombardments back in 1945: Nagasaki and Hiroshima. The first two parts, Springtime in Nagasaki and Summer in Nagasaki, reflect the normal atmosphere of a Japanese city, along with some of the rising premonitions of what would happen on August 9, 1945.

Autumn in Hiroshima and Winter in Hiroshima musically mirror what happened after August 6, 1945, when he survived one of the most lunatic and barbaric war crimes ever committed by mankind. The Fifth Season recording captures the time after these events took place and the lasting effects on Mr. H.T. and others—the so-called “endless season.”

How did the subject matter affect you personally and creatively when you explored it so deeply?

Violence against human beings on such a low and immoral level of consciousness affects everybody. Of course, it was the story Mr. H.T. came up with that gave the project a very personal meaning. As far as musical and emotional impact is concerned, this series represents some of the most important work Tangerine Dream has ever done.

Describe your process for composing music.

It’s so simple that I laugh when I think about it. The way I do it is to forget myself. I always fail when I step into a working process with my ego in which I say “Here I am. I know myself. I’m the one who is doing whatever needs to be done.” It works perfectly the other way around when I get lost in sounds and musical structures. For instance, when a composition is 60 percent finished, it takes you over and gets a life of its own. It’s as if another individual is asking questions like “Hey, is it better this way or that way?” It’s a very, very private and intimate process. Sometimes, it gets to the point where you as a conscious person, sitting in front of your computer, say “Hey, that’s it. The piece is ready.” Then you listen to it again and all of a sudden realize “Wow, it’s not ready. The piece is asking for something better and different.” It can be painful when a piece of music takes over and forces you to go in another direction you never would have thought of previously. Suddenly, you’re in a process of getting deeper and deeper into it. And sometimes you’ll need a sound for a piece of music which is 80 or 90 percent finished and you won’t find the bloody sound. You’ll run through all your software and sound banks and nothing fits. If you have that situation three or four times a day, it really hurts. It’s very time consuming, aggravating and hell sometimes.

The most enjoyable moments happen when a piece of music is really finished and that’s it. It’s the most relaxing feeling I can think of. You just flip back into your chair, relax and listen to the music as if it wasn’t you that composed it. It’s an interesting situation because it’s so removed from your ego. The piece exists and even as its composer, you can participate in the music as just a listener. The music takes on a life of its own.

Early Tangerine Dream concerts were entirely based on improvisation. What role does improvisation play for you today?

The composition process usually begins with some improvisation. You start playing around with rhythmic structures, chords or melodies in a search for the right sound. No composer on the planet is as good as Mozart was though. He just wrote down what he heard. That took incredible genius on the part of the great composers. But that time is over. I can’t think of anyone who is able to just translate what’s in their head in that way anymore. You can hear melodies and entire structures of a piece in your imagination, but the way of transforming that into a listenable audio signal has changed, particularly because of technology.

As far as improvisation during concerts is concerned, there isn’t that much improvisation during our shows anymore because the working tools are completely different. The equipment today allows you to do things you couldn’t even dream of 20 years ago. But now there is a need to control various devices. You can’t just sit there, switch on a sequence and start playing some lines over it or add chords or drumming to it. Today, you have to structure things in advance and go much deeper into things. We’re not in 1973 anymore.

Tell me how you take advantage of today’s electronic music technology.

Working and composing is much easier now with all of the modern tools. These days, I work purely from a software-driven, sequencer-based computer system using plug-ins and all the sounds that are currently available. Some are specifically designed for our needs, but it’s mostly the same stuff most composers use these days. The most significant change for me in recent times is that I got rid of all the outboard equipment we had through the years—tons and tons of analog and digital gear.

To me, the instruments are just a materialization of your thoughts and consciousness. They reflect what you feel and the way you explore what’s inside you. My view is that maybe five percent or less of music, sounds and audio signals that are possible to produce are produced. There’s so much more and the future will explain what I mean. What matters is how you step across the border from fingerwork to mental work. That’s the time we’re entering now. It’s a very adventurous era. We’re leaving the field of strings, keys and knobs and moving deeply into an abstract form of creating sounds. It’s something absolutely new which hasn’t been on the scene before. You start becoming more of a sound sculptor instead of a soloist who is showing how well you are trained and how many hours you have spent learning your instrument.

Electronic music-making software is now ubiquitous—even on cell phones. How is the widespread availability of these tools affecting the art of composition?

Creativity, fantasy and musical abilities have nothing to do with new technology. Technology is like a new toy shop. You have to sort out what is necessary for your own aims in music and forget about the rest. Before all of this technology, composers only had the piano to save their musical thoughts using the four basic parameters. Yet look at how many great compositions were created by the masters, compared with today when so much rubbish has been left for posterity.

You once said “Politics, religion and science filed their bankruptcy claims long ago. Art can at least attempt to convey the truth.” How do you define the truth?

The 7 billion people on this planet have 7 billion truths. It’s said that truth can be related to your perceptions, lifestyle, philosophies, and religion. I don’t think those kinds of dialectics work. For me, truth is beyond all of that. Everyone who wants to tell you the truth fails. They fail before they even start talking about it. I don’t believe in churches anymore, so that is not the truth. I don’t believe in politics. That is definitely not the truth. It’s the opposite. So, what’s left? I believe everybody has to look deeply into his or her own psyche. If there is a place where truth resides, you will find it within you.

How does your music communicate your truth?

I always try to be as honest as possible. You won’t find any gimmicks in our music or anything that tries to guide people in the wrong direction through tricky types of business. I hate all of that. I just tell people a story—my story. It’s about communication with other people I work with. That’s about it as far as my knowledge of it goes. If listeners feel the same way, they’ll listen to the music again and again. They’re on the same level—whatever level that is. I don’t want to give it a name, but it’s a level that offers the most honesty possible.

You’ve spent a lot of time studying comparative religions. Has that work provided you with a particular spiritual perspective?

I can tell you that I don’t believe in death. It’s something that’s told to people by churches and some leaders with a certain aim in mind. Nothing dies, even if it disappears from our visual perception and even if we can’t reach it with our other senses. My personal studies, which have been going on for 45 years since the age of 15, tell me there is a completely different system and world beyond everything we are experiencing and the system we are jailed in. From here, it goes up. You could call it an elevator. Your understanding depends on if you can open yourself up to completely new and different ideas. I hate old-fashioned thinking on this. To me, the idea that you can get into paradise after dying and live forever with angels and nice people is bullshit. Real spirituality is much more sophisticated and requires a much more open-minded consciousness. Having said that, I don’t want to say I’m right and others are wrong. This is just my way.

In 1998, you chose to completely break free from record companies and founded your own label. Tell me about that decision.

Over the years, I’ve signed up with most of the existing record labels in Europe, America, Japan, and Australia. I was frustrated because none of them ever understood what we were trying to do. It’s a story that’s familiar to a lot of artists. You want your music available on the entire planet so anyone can get it in a local record shop and listen to it. But those huge companies have no interest at all in the music itself. It’s something we’ve experienced many, many times. They’re just looking at the stock exchange and your sales figures and figuring out how they can prostitute you. So we founded our own label to get away from that. It wasn’t easy to do. We struggled quite a bit initially, but it turned out to be very successful. It’s a very cool and relaxed situation. You can release what you want, when you want. There is nobody who can interfere with what you want to say.

Recent years have seen you completely re-record several earlier Tangerine Dream and solo albums. What makes you want to pursue that path given all the new music you have in your head?

The main reason is that long ago we signed contracts with those big labels that did not allow us to use the original master recordings for our own releases. We’ve had huge trouble with companies like Virgin who have kept all of our earlier releases under the carpet. They didn’t reissue them very well and haven’t brought them up to the latest technical standards. After years of complaining, writing and talking, we decided to re-record some of the stuff in order to make sure the compositions are available on the market in the highest quality possible.

We are composers and in it for the music. All I want to do is express my philosophy of life in music. The businessmen never understood that. So there was no other way to keep the music and its spirit alive without re-recording it. For instance, the people at Virgin have enough money and they’re not going to be buried with it. I wrote the president of EMI a letter saying “Hey man, you’ve got no problems money-wise, so let me out of my obligations.” All he said was “Look at your contract.” I have to say that making the re-recordings is frustrating because you have to step back in time to an earlier part of your life. You are very close to the original spirit because you did it yourself originally with other colleagues, but you don’t necessarily want to feel the same things again. However, you have to try, otherwise you can’t re-record the stuff.

Did you and Jerome have an equal relationship when he was a part of Tangerine Dream?

Sometimes yes, if it was working fine. If not, then no. Not at all. [laughs]

Our working relationship shifted from being very harmonic and cool to very, very furious with horrifying fights about things we don’t like. For instance, he was moving very strongly in the DJ direction. He is also very influenced by new things like drum and bass, hip-hop, trip-hop, and breakbeats. All of that is okay, but not my piece of cake. Someone who is working in that area a lot that collaborates with someone else is going to bring in those influences. Some of those things are great and fit in perfectly, but he sometimes wanted to integrate a very deep bass sound that made subwoofers collapse. I’d say it should be limited and he’d say “No! It should go on. It should blast out.” [laughs] Another example is when we were going into the world of Dante, I could not imagine in any way putting some breakbeats in there. The whole aim was to create something different from that which exists in the modern music scene. So, we had some musical arguments in which we couldn’t meet one another.

What I liked most about Jerome’s contribution is the way he very often turned things upside down. He was chosen to become part of the band simply because of his musical talent. He is not a trained musician like most of the other colleagues were. I didn’t train him myself. He was trained a bit by others. He has a great sense for sounds and can put things together in a very unique way. He showed me some unusual ways of using sounds and rhythms. We had a real exchange of ideas and strategies. That also holds true for when we were stepping into the old scenery of Tangerine Dream and talking about remastering and re-recording. It was quite interesting to hear his opinions because he wasn’t part of those times. He was hearing and experiencing as would someone reading very old books.

Jerome departed because he wanted to start his solo career, which is more than understandable after spending 16 years with the band. It’s a very normal process. I wish him all the best and a lot of creative power to realize all his future projects.

What’s your perspective on the influence Tangerine Dream has had on the electronica movement?

I think it’s much greater than a lot of people are willing to tell the public. [laughs] I know a lot of very famous musicians who know a lot of Tangerine Dream’s work—some of them know all of it. For whatever reason, it’s not interesting enough for the press to write about. However, the influence is really immense. The fact is that in 1970, we started a kind of music with sequencers and electronics that was completely unknown to people. Now, it’s common to use those things. In the late '70s, I said “One day everybody will use a synthesizer” and people laughed their heads off. One journalist called me an idiot and said I didn’t understand the music scene and that the guitar and piano will never fade away. I never said those things will fade away. But I did say there will be a development in sound and music creation using recording techniques that have their roots in what was accomplished in the early '70s. That’s the truth and it can be verified by anyone that goes into most studios or looks at a typical stage set-up today.

Tell me about Tangerine Dream’s founding principles.

I’ve never really talked about it before, but the whole Tangerine Dream thing always had one idea that’s run across its history. It’s the idea of starting with unorganized chaos and moving on to reach the highest possible point of organized music. We’re always trying to organize sounds, but not in a way that classical music is organized or in the way that a band playing together perfectly can sound. It’s more about a subconscious music feel and working with the pool of given sound available. Humans can create sounds out of things that are very abstract. It’s about getting through the mental barriers to create music that is very personal, subjective and organized.

Tangerine Dream is in fact a concept. The concept can have people who are guiding it and developing it by being good colleagues and creators. It’s very hard to discuss these deep philosophies behind the music because in my view, the real music can’t be heard. That’s maybe a paradox to some, but not to me. For instance, when I listen to a Bach symphony, the real essence of the music begins when what you can hear is over. When the music stops, the real music starts.

How would you encapsulate Tangerine Dream’s legacy?

Tangerine Dream is nothing more than us helping ourselves and others get out of jail. Everybody who feels trapped or jailed in this life should use our music to have a glimpse of an idea of what could be next.

Website:

Tangerine Dream