Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

The Aristocrats

Breaking the Fourth Wall

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2016 Anil Prasad.

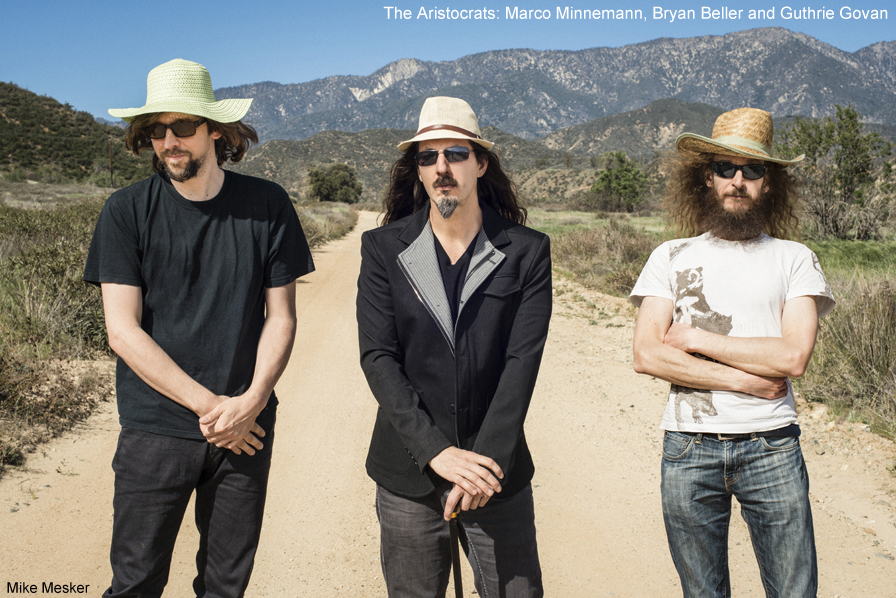

One thing’s certain when someone attends an Aristocrats show: they’re not going to be bored. The instrumental rock trio, which includes bassist Bryan Beller, guitarist Guthrie Govan and drummer Marco Minnemann, uniquely bridges intensity, accessibility and eccentricity. Their gigs are raucous affairs concertgoers appreciate on multiple levels. Their jaws might be agape at the band’s virtuoso playing. They might be laughing at its jokes or the humorous constructs of its compositions. Perhaps they’re simply captivated by the off-the-charts energy the act projects night after night.

The Aristocrats also have a rebellious streak. The group is completely independent, handling the entirety of its recording, performance and marketing elements in-house. It refuses to compromise on any part of its output or public presence. Its three studio albums, including its most recent release Tres Caballeros, are emblematic of its overall worldview. They’re drenched in defiance with writing designed to showcase their disinterest in safe forms and tendencies towards pieces that unite fusion, metal, progressive rock, and uncategorizable Zappa-esque leanings.

While the group has a fun persona, its inner workings are incredibly serious. The band has fought against music industry odds since forming in 2011 to get to the point it’s at today. Its members have taken a sophisticated approach towards managing the band's business, propelling its last two recordings into the Billboard jazz charts, and creating a global profile enabling it to perform worldwide to ever-increasing audiences.

Beller took time out from his non-stop tour schedule to reflect on both The Aristrocrats’ evolution and his own personal career journey to date, including his work with Joe Satriani and Mike Keneally.

Describe the mission of The Aristocrats.

We’re trying to play instrumental music that’s complex and outside of the mainstream, and have a good time doing it. Our songs have more notes than your average pop or rock song, more time signatures than your average progressive song, and are louder than your average jazz-fusion song. We would never compare ourselves to Frank Zappa, but we have that same kind of ethos of not taking ourselves too seriously.

Now, speaking just for myself, an even higher purpose is that I want the band to inspire other musicians. I grew up with bands like Rush, Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd. For other generations, it was Dream Theater, John Scofield, Steve Vai, and Joe Satriani. All of these people made huge impacts on other musicians and inspired them to go out and write their own music. I would love for The Aristocrats to be one of those bands that influenced other musicians in a positive way.

Tell me about the band’s creative process.

We all start completely isolated from one another. We don’t collaborate when we write. We produce completely finished demos for each other. We’re all capable of doing that. I can program drums really well, but I’m a terrible guitarist. I can play just enough guitar to create a demo. Marco plays 6- and 7-string guitar all over his records, as well as bass, and of course, he’s a great drummer. Now, Guthrie is a freak. He’s a better bass player than I am and that’s pretty sobering, but it’s true. Drum programming is something he does as well, even though he doesn’t like doing it.

After we make our own demos and then give them to each other, it’s at that point we trust everyone to do what they’re supposed to do. We get together to rehearse before we record. We’ll talk back and forth and say things like “We should shorten this part” or “What if I added this bit here?” But in general, the demos are pretty reflective of what happens. Of course, they don’t sound like The Aristocrats in the demo phase. But by the time, Marco, Guthrie or I provide input and voices, it does become an Aristocrats piece.

Did that creative process evolve further for Tres Caballeros?

It did. For the first two records, we went right into the studio and it would be the first time we played each other’s songs. But what we found is three or four weeks after we started playing them live, the songs developed deeper identities. There would be additional bits we’d do that we’d wish were on the recorded version. At the end of the day, we’re really a live band. It’s when we perform that everything really comes alive.

So, for Tres Caballeros, we decided to do a residency at Alvas Showroom in San Pedro, California. We booked the main room for a week. We rehearsed there for three days and then did four shows in a row. We played all the new material live and the songs evolved a bit. Having audiences also helped. It provides a feel for what’s working and what’s not for them. Is something too long? Is something too weird? We might ask those questions of ourselves after those gigs. After those shows, we went into the studio and recorded the album. That was a really good model. The demos still remained reflective of what we’re playing, but the live element was introduced as well. What ended up on the record was the live expression of those demos.

What’s the biggest challenge the band faces during the creative process?

We’re fortunate in that we’re all speaking the same musical language. The only challenge we have is sorting through which of Marco’s 20 songs should be on the album. [laughs] He writes so much material. He’s a writing machine. He’ll send us song after song after song and we have to figure out which are the best three for The Aristocrats, and Marco has to agree. Sometimes Marco’s pieces will have a million layers, and we have to decide whether or not the piece will work as a trio playing it. As for Guthrie and I, we can barely write three songs for each record. [laughs]

Several of the band’s pieces are infused with sarcasm and irony. Describe how that translates into the compositional element.

It depends on the song. Some songs are meant to be really dumb. [laughs] The song “Stupid 7” that starts Tres Caballeros is written in 7, which is the standard issue progressive rock time signature. So, that was something we were making fun of. Marco decided to write the nastiest, shittiest-sounding riff in 7 he could. That’s the sizzle. But the steak is that the arrangement is really hard and there are a lot of weird further time signature changes. It’s a complex song to play. It sounds fast, punky and kind of “fuck you.”

My song “Smuggler’s Corridor” was the result of me listening to a lot of Ween and Calexico. Somehow, that song came out. It ended up sounding a lot like a Quentin Tarantino soundtrack. That wasn’t my intention, but that’s what it wanted to be. There are all sorts of ways you can take the piss out of stuff. I had the idea of a spaghetti western, and right there, the irony is baked into the cake.

Guthrie has a song called “The Kentucky Meat Shower” on Tres Caballeros. First of all, the song is called “The Kentucky Meat Shower.” [laughs] It’s about something that happened in Kentucky in the 1860s. One day, a whole bunch of red meat fell from the sky in a little Kentucky town called Rankin. What they think is a flock of buzzards descended on some dead cows and ate the meat. They then ascended into the sky and one buzzard vomited the meat out. Buzzards copy each other when they’re in a flock, so it’s believed the rest of the buzzards vomited their meat out too. So, all this meat fell on the town. The song has a chicken pickin’ idiomatic nature. It has several different movements that represent the different phases of that event.

What makes you want to say “fuck you” to formats and genres within your music?

None of us wants to be this generation’s Yngwie Malmsteen. When I say that, I don’t mean to say he isn’t a great musician, but he projects this idea of being so serious. It’s almost a caricature. There are a lot artists that put out this “We’re so fucking great” vibe. Now, of course people come to an Aristocrats show to have their heads blown off. That’s part of the deal with this genre. But we want people to have a good time. We want them to laugh. And we want the audience all in on the joke. We’re not towering over the audience. It’s like breaking the fourth wall in a movie. You know, when the actor or actress looks right into the camera and says “Yeah, it’s all bullshit.” That’s what we want to pull off, but at the same time, every once in a while there will be a fairly serious-sounding song. It can’t all be rollicking, fast, fuck-you music. [laughs] We want to have peaks, valleys, dynamics, and contrasts in textures during the show.

What progression do you feel Tres Caballeros represents for the band?

We used more overdubbing, which was the big difference with the latest album. We only hinted at that in the second album. There were two songs that had textural sections and that was it. For the third record, we all said “Fuck it. Let’s make a studio album.” We knew the arrangements could be played live because of the residency we did before recording. So, we thought we’d see what we could do in addition in the studio. Some of my favorite moments were after basics were laid down and we created additional textures for songs. Marco whipped together a really intense series of overdubs for the song “ZZ Top” in five hours, incorporating keyboard, guitar and percussion layers. For the piece “Pig’s Day Off,” Guthrie and I were going through guitar parts and creating additional textures. It was during those moments when we really felt collaborative on the songs. We each took turns in the producer’s chair. If it’s our song, we produced it.

Describe the roles the band members have beyond the music.

From the general view, I’m the band’s manager. So my role outside of the music is representing the interests of The Aristocrats as a unit. I don’t run the band, but I’m the band’s unifying voice to the world. That means I interface with booking agents and our publicity people. We are our own record label. We have a very small organization with little overhead. We’re mostly doing everything ourselves. We’re all big believers in that. We never felt the need to go with a record label to finance our record and then own it. That’s ridiculous. I’m really proud of our scrappy, independent team that has worked so hard and stirred shit up in this genre for us.

Guthrie’s other role is to hate being classified as a guitar hero. [laughs] One of the reasons he’s in the band is that the whole guitar hero worship thing wasn’t something he was interested in. It’s why Guthrie doesn’t have a profile like Joe Satriani or Steve Vai. If Guthrie wanted to build a star machine around himself, he could have done it a long time ago. He has absolutely no interest in that at all. He wants to be part of a band and play interesting instrumental music. He also just wants to relax after the show, and have a beer and a cigarette.

Marco is the guy who has his fingers in the most pies. He’s got the most side projects going. He’s constantly releasing solo albums. He’s a whirlwind of energy, whereas Guthrie is extremely mellow. So, there’s a good energy balance there. Marco is also by far the biggest showman on stage of the three of us. He’s a natural performer and it shows in everything he does. Guthrie and I are less so. Guthrie is the quiet British guitar wizard. I’ll move around a little bit and try to hold it all together, but it’s nothing like what Marco does. I always feel like my feet are on the ground so Marco and Guthrie can fly.

What’s your perspective on why The Aristocrats have achieved a successful trajectory against the industry odds?

If you sit there and analyze The Aristocrats’ trajectory, it doesn’t make any sense. What came together from the primordial ooze to put us in a position in which we’re on the G3 bill with Steve Vai and Joe Satriani is a mystery to me. My guess is it’s because we’re a band and not a single artist. I think that makes a difference in some intangible way. I also think we were very lucky that no-one had understood the potential Guthrie had in our community. Until The Aristocrats, he had never toured the United States with his own project. Most of the work he had done was in Europe and in Asia. The most steady gig he had was the one he regularly did 10 miles from his house in England. People were coming from all over the world to see it. Some of the trajectory is related to that.

Marco is responsible for it as well. He gathered a lot of fans from all the projects he’s done, including working with Adrian Belew and Steven Wilson. He’s played professionally across Europe for a lot of years. He’s also a really interesting songwriter. I think drummers get a bad rap as people that don’t write songs or play other instruments. Marco does both.

Then there’s me. Whatever system I developed in corporate management and from assisting the band is also helping us get from one level to another. I had them all in place for The Aristocrats because of my SWR experience and the work I’ve done for Mike Keneally. Mike and I have done lots of limited tours across the U.S. together. Because I had a background in business, I was able to put together spreadsheets, cost estimates and budgets for some of those tours. It’s just the way my brain works. So, I had this machine already that got tweaked and adapted for The Aristocrats.

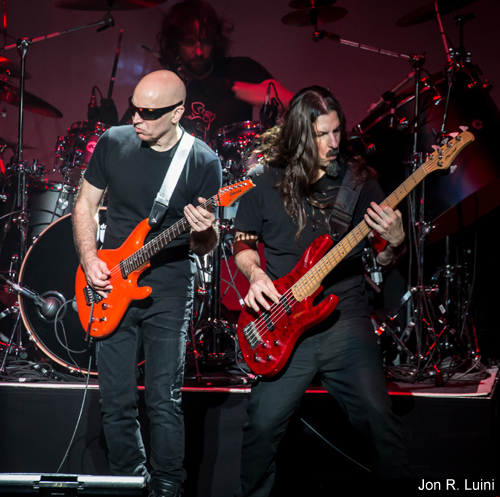

You’ve been a member of Joe Satriani’s band since 2013. Reflect on that experience.

The Satriani gig is a very old school one in a way. Joe just wants someone who’s going to be a real rock bass player, with big rock sounds and distortion, but is also smooth and dark when necessary. He wants a pro who can cover the gamut, lay it down, and show up and be a no-bullshit guy who gets the job done. That’s because Joe is that as well. He’s a no-bullshit, no-drama guy. He’s very down to earth and doesn’t put on airs at all. What you see is what you get and he’s very cool to work for.

Musically, Joe’s very direct about what he wants. He wants his songs played with a lot of energy, but when it’s time to play eighth notes, it’s time to play eighth notes and that’s that. Having said that, we’re doing some stuff in the live set now that previous bands haven’t. I think it’s because he feels comfortable that we’ll push him a little bit and he likes that. There are more instrumental interactions between band members now. There’s more call and response stuff. We add little twists to the arrangements of songs that have been around for a long time. They’re relatively small changes, but the fans really notice them. They’ve come up to me on a few occasions and said “Wow, Joe is doing stuff he never did before with you guys.” I respond “That’s cool. It means we’re doing our job, which is to make Joe comfortable, sound good, and feel good.” At the end of the day, our job is for everyone to come out and feel they saw the best Satriani show they could see.

Is it more than just a job?

Sure, because it’s music, but we’re sidemen and our job is to make sure the artist is completely satisfied. I really look at it that way. Maybe it’s because I have a corporate background. I had a straight job for years. It helps defining what it means to be in a band versus working for someone else. The Aristocrats are a collective entity. The three of us are constantly talking about how to refine things. Sometimes there are business conversations. Sometimes it’s about music. Sometimes it’s as mundane as talking about how we’re going to travel from one city to another on the road. We all have to make decisions in that band.

With the Satriani gig, it’s a conveyer belt. You get on and the belt moves. Your job is to be on that belt. I see that as a positive thing. It’s a well-oiled machine. It’s built to run like clockwork. All you have to do is show up, play well and don’t be a dick. I appreciate well-organized entities. Life is unpredictable enough when you’re touring for 10 months in a row. I enjoy some predictability. I think there’s too much preciousness from musicians who are hoping to get hired as a sideman. Satriani is a great sideman gig in our genre. He’s the top-selling artist in it. He does really well and has done so for 25 years. There’s a reason for that. It’s because he delivers the goods to the people who love his music every time. So, it’s a great gig and I just want to make sure I’m working hard for him and the rest takes care of itself. He knows what he’s doing.

Tell me about the corporate day jobs you held with SWR that inform your perspective.

I was the Vice President of Product Development for SWR Bass Amplifiers. But to get to that point, I had to do lots of other jobs. I started out in the late ‘90s in their version of the mail room, testing amplifiers for $8 an hour. Then I became a customer service manager, which is a very difficult job, for only slightly more. Next, I did artist relations and then did export management. I learned a lot about European business in that role. I then became the product development manager. That was fun because I got to work with engineers and have an impact on the products we put out. After that, I got involved in marketing, and was finally promoted to Vice President. I was part of a three-person team that was essentially running the company at that point. Fender then bought SWR in 2003. They bought me too, for two years. I managed the transition from SWR into the Fender corporate umbrella. I learned even more about what it’s like to have a real job, including creating PowerPoint presentations, Excel spreadsheets and budgets. It involved every aspect of the business you can imagine. In 2005, after eight years of that, I quit, with no plan other than I was going to get back into being a full-time musician again. The reason I got a job in the first place is I was broke and in debt and didn’t want to live like that anymore.

Your last two solo albums View and Thanks in Advance are focused on compositions and melodic elements. Describe what you were going for with each.

Each was made in a completely different mindset. View was my first album and I was working out a lot of angst in it. There’s a story arc on that album that deals with a slow, self-destructive temper tantrum. The question I ask at the end of it is “What did I just do?” Thanks in Advance is an album about working towards making a breakthrough from that kind of negative thinking and getting to a space in which gratitude is a context for day-to-day living. So, those are my high-minded takes on how those records work.

I feel my solo work should tell stories and be somewhat conceptual. My favorite albums are by Pink Floyd and Nine Inch Nails. I feel the weight of the story line on all of their albums. Even with instrumental rock or fusion albums, I still want to feel like a story is being told and that the songs work together as an entity. I know that’s more and more old-fashioned these days, but I really do value those things when I make albums.

Your solo albums don’t conform to many people’s idea of what a record conceived by an instrumentally-focused bass player might do. Discuss defying those expectations.

I made that choice early on when I decided not to be that kind of player. The big joke of my career is that I’ve been thrust into this world in which everyone is a hot-shot player. I’m not. There are so many bass players that can play complete circles around me, technically. I’m really a meat-and-potatoes bass player. I never worked on technique when I was a kid. I only worked on learning songs. If I couldn’t learn the song because there was a technique I couldn’t play, then I would figure out a way to do it. But I never sat and practiced scales with a metronome. I never practiced right-hand technique. I only practice for gigs, recordings and making sounds. I’ll sit in rehearsal rooms with my pedal board and tweak forever until I get something I know will work live.

As far as making a “bass player’s album,” the truth is, to make that album, you have to be the bass player’s bassist, which means you went through certain motions when you were younger, focusing on playing techniques and advanced fingering—the things that make stuff exciting to listen to for some people. I can listen to some of that stuff. There are great people who have worked out how to do this uniquely, like Doug Johns. He has a cool, interesting combination of techniques on his totally bass-focused records. It’s like if Victor Wooten was in Tower of Power. It’s cool.

I think the standard for bass players’ bassist albums is very high. So, it didn’t matter to me whether or not I wanted to do that, because I never had the technique to make it happen. I listen to Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Yes, Metallica, and Slayer. I like some fusion, like Jaco Pastorius and the early Chick Corea Elektric Band stuff, like the Eye of the Beholder album. I think John Patitucci is a great jazz-fusion player who has a lot of soul. I’m glad there are other bass players making those albums, so I don’t have to. [laughs]

You’ve worked with Mike Keneally for decades. Explore the beginnings of that working relationship and what it’s meant for your musical development.

I first met Mike when I took Scott Thunes’ place in Dweezil Zappa's band. Mike was good friends with Scott and wasn’t happy when Dweezil let Scott go. Joe Travers, my longtime friend going back to my Berklee College of Music days, introduced me to Mike’s music. I fell in love with it. Mike’s music is one of the direct descendants of Frank Zappa’s sarcastic muso rock thing. I thought “Wow, that’s the kind of music I always wanted to play.” I tried to convince Mike I could play his music, but he wasn’t interested. [laughs] It was really funny. We’d be in rehearsals with Dweezil and I would play licks from Mike’s music during breaks and Mike would look the other way. But that didn’t go on for long. Eventually, Mike and I became good friends. I ended up doing a couple of gigs with Mike outside of Dweezil’s thing and he asked me to join his band.

For 20 years now, Mike and I have had an incredible, fruitful, mutually beneficial friendship and partnership. I’ve recorded a bunch of records with him. I look at him as a mentor. As a producer and arranger, nobody does what he does. He’s open-minded and broadened my horizons in a way I could never have done otherwise. And that’s just the musical part. The friendship part is great too. He got me the gigs with Dethklok and Joe Satriani. How do you repay a guy like that? I will always be indebted to Mike and be in awe of him.

What do you consider the highlights of your work with Keneally?

Mike wrote an album called The Universe Will Provide. It was an orchestral composition commissioned by the Metropole Orkestre in Holland. It’s an extremely dense and complex piece of music. It rewards repeated listening. It’s a refreshing piece that is so rich and beautiful. I fell in love with it when I first heard it. It was played once in concert and then Mike was asked to do a repeat performance. I was asked to be in the rock rhythm section of the orchestra for the second performance. It required every bit of my mental, emotional, physical, and spiritual faculties to play that piece of music. I really, really enjoyed it.

Mike has so many other records. We’ve done a lot of cool gigs. I love the early trio stuff with Toss Panos. I also really loved the quintet tour we did with Joe Travers, Griff Peters and Rick Musallam. We called it “The Same Band Tour.” The same lineup was used for The Bryan Beller Band and The Mike Keneally band. We were playing my material and Mike’s Scambot 1 and Dog stuff. Mike’s repertoire goes back 20 years and is 15 albums deep. There’s so much great music. Mike really is the guy who, in a lot of ways, made me the musician I am today.

You’ve released all your solo and Aristocrats albums independently. Tell me about that decision.

These days, it’s lame to go with a label. The challenge is to break out of the long tail—the glut of first-time projects that flood the Internet today because anyone can make and release a record. The tools are there for everyone to try and build and nurture an audience in order to grow a career. But at the end of the day, people have to want the project. First, you have to make a great record. So, I would say put your heart and soul into your records. Then, when you’re done, you have to say to yourself “Okay, I can either find $30,000 to release and market my album or I have to find someone to give me $30,000 to do that and in exchange for that, they get to own it forever, while I get pennies on the dollar every time someone buys it.” And as we know, people are buying less and less music every day.

I was always the guy that was going to release albums myself and form an independent business entity, because my brain organizes things. I create structures, systems and business templates. But you don’t have to be as hyper-organized as me to realize the benefits of doing it yourself. The other people out there doing it don’t necessarily know any better than we do. They’re just doing it because they’re doing it. Also, remember, when you’re with a label, your resources are shared. You’re not going to be the only act the label handles. They may have many acts to deal with. They’ll never give you the same attention you can give yourself. Now, there’s a sacrifice involved in that when you do it yourself, you may spend more time taking care of the business end than maybe you would on the music. But that’s what’s on the menu these days as I see it.

How do you make up for the lack of income from streaming and piracy?

We’re not sitting here trying to figure out how The Aristocrats are going to beat the system. Those trends are much bigger than us. All we can do is try to make great music that people want to hear. If people want to buy a concert ticket and come see us, buy a CD or a deluxe edition, purchase a single MP3 single, or just stream the whole thing, it’s all valuable. We’re just going to keep doing what we’re doing and that stuff will take care of itself. If The Aristocrats ever becomes completely unviable, then we’ll deal with that at that point.

The world of the Internet is a “share-ocracy” in which if people find something interesting, they will share it with others. You just can’t argue with the results. Now, that might mean there’s a cat video that gets watched 15 million times, but you know what? That’s real. Fifteen million people wanted to watch that cat video. See, this is the thing. It goes back to the preciousness discussion we had—the idea of “I am an artiste.” Look, The Aristocrats aren’t in the music business. Like everyone else, we’re in the entertainment business. We’re lucky if someone takes time out of their day to listen to our music. Maybe they take three hours of their day if they’re coming to see a show. They have their own jobs. They might be raising kids or taking care of someone else in their family. Whatever it is they do to support themselves, whatever it is they do during the day, they decided to spend a little bit of their disposable income on pure entertainment. They wanted something that makes them happy for a little while. Our job is to deliver entertainment. Is there art in entertainment? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. I want every Aristocrats record to be the best it can be. I’m not thinking “This is going to entertain people.” But hopefully people are entertained enough to be interested and keep coming back. If they are, they are. If not, the people have spoken.

The challenge most artists have is getting people to find their music within the enormous “share-ocracy” you described.

Here’s the thing. The most aggressive, viral marketing campaign in the world won’t let you sell something that people don’t want to hear. Why do people break out of the long tail? It’s because there’s something interesting going on. It’s easy to blame the system. But as I said, the system is the system. If you want to make your job trying to change the system, then you’re not a musician anymore. You’re something else.

Isn’t it possible to be both?

If you’re up for that. Some people say what The Aristocrats did represented a small shift in the system because we’re completely independent. But that’s not what we set out to do. We just wanted to make music, go on tour, sell records, be able to eat, and not have the furniture taken away.

If you’ve decided to get involved in the world of music, you’re already somewhere in which the odds are very low that you can have any success at all. I’m so grateful The Aristocrats somehow came into existence. I still can’t believe what happened. And if I tried to do it on purpose, it probably wouldn’t have happened. If I sat back in 2010 and said “I know what we’re going to do. We’ll form a power trio. We’ll find the world’s greatest guitarist that no-one has ever heard of and all the magazines are going to write about us. We’ll have dirty song titles and that way people will like us because they think we’re counter-cultural. There are only three people in the band, so we’ll make more money than if there were four or five. We’re also going to make it in Japan. After that, we’ll play in India.” That wouldn’t have worked. But here we are, and it’s all happened.

Having said all of that, there’s something else to consider, too. People trying to sell things in any industry sometimes point the finger everywhere but themselves. Here’s a harsh example. There was once an ad campaign in which a company came out with a new brand of dog food. They had the best ad campaign. They did extensive market research. They found out what specific dog owners were looking for in dog food. They bought advertising on all the right channels that target those dog owners. They got interviews placed. They had a great viral marketing campaign. But the sales were really disappointing. The company had a big meeting about it. The employees said “We don’t understand why this isn’t working. We’ve done everything we can do.” Then a guy in the back of the room said “Maybe the dogs didn’t like it.”

Like I said, that sounds harsh. But in a kind of higher-plane way of interpreting reality, it isn’t harsh. It just is. Life is filled with events. Some of them are enjoyable, some of them, maybe not as much. And another way to look at it is, every life event is an educational opportunity. Or, in other less high-falutin’ words, what can I learn from this thing that didn’t go the way I wanted or expected it to? And how can I put myself into action to create a better—or even completely new and different—result?

A dear friend of mine once said something to me that impacted me deeply: “The Universe is a kind and patient teacher. It just keeps teaching until we get it right.” “Right” might not look like I thought it would, but that doesn’t make it wrong. Only I make it wrong.

So, bringing all this metaphysical talk back down to ground level, all I’m saying is this: If something isn’t working or isn’t being well-received, try something else. If that doesn’t work, try something else. And again. And again. And again. Don’t get hung up on whether or not Spotify is ruining your chances of being a professional musician or if Facebook is tipping the scales of its news feed to this or that, or if your YouTube hits aren’t as numerous as the next person’s, or any particular macro trend of the day. That’s a way of transferring the cause in the matter to something outside your immediate ability to affect it. Make the best music you can, put it out there, and take what you get. The rest is noise.