Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

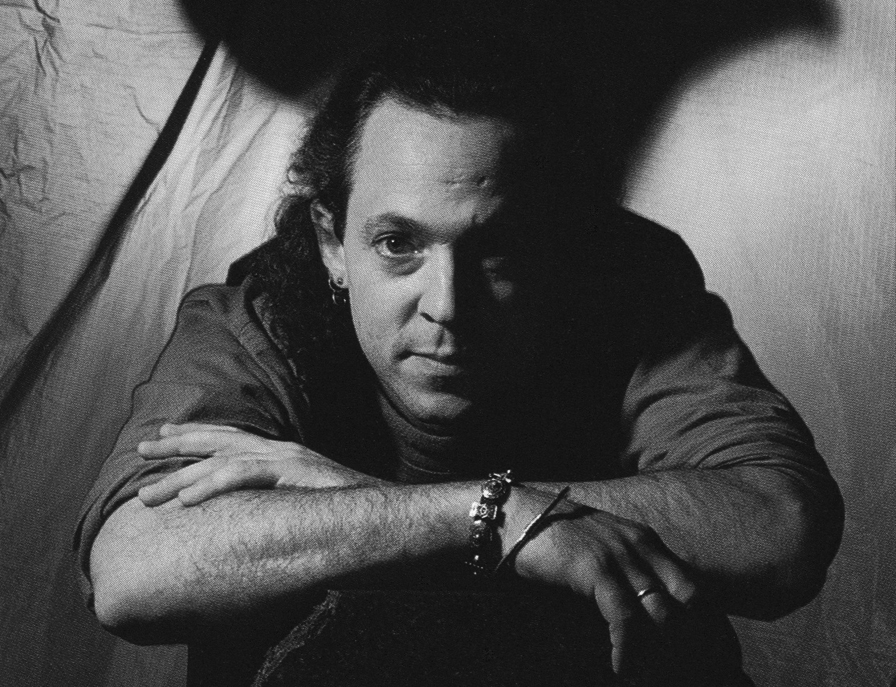

David Torn

Every Mind Has to Be Defused

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1990 Anil Prasad.

When avant-guitarist David Torn switched labels from ECM to Windham Hill in 1990, more than a few eyebrows were raised. How was it possible for the lone practitioner of "arrogant ambient" to join forces with the world's largest new age purveyor?

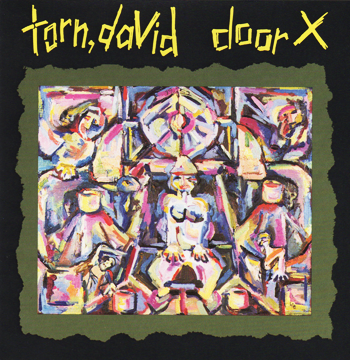

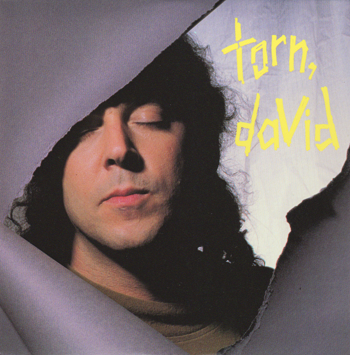

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it turned out to be a brief relationship, yielding a single album in Door X. The disc offered a combination of accessible songs and concise instrumentals. Door X was a significant departure from the expansive Cloud About Mercury, Torn's previous release from 1986. It was a groundbreaking, visionary effort that captured a seamless collaboration between Torn, drummer Bill Bruford, bassist Tony Levin and trumpet player Mark Isham.

This interview focuses on the making of Door X, Cloud About Mercury and the technology Torn employed at the time. Commentary about the aftermath of Door X is covered in the 1995 Innerviews feature "Fate is not completely decided."

Describe the genesis of Door X.

The way the record started was I knew that I was going to do some vocals, but I didn't know what beyond "Voodoo Chile." So, when I went into the studio, I had all of this other material written which was mostly instrumental. I kept thinking "Well, this is really weird. I have these instrumentals. How am I going to add vocals to these?" And that felt really fake. So, I scrapped all of this other music and started writing songs in the studio. That felt great because I could do it according to my emotional state, which meant that I could write really fast, get into a specific mood or state of mind, and achieve it really quickly while musicians were around. It let me get a roughness into the songwriting process which would have been destroyed had I signed a pop record deal somewhere. I could have used songs like "Time Bomb" as a basis for a pop deal, but the industry would have wanted everything to be creamy, smooth and real normal-sounding. So, I signed with Windham Hill and fucked with their heads when I started delivering these vocals. They were so knocked out of the picture. They were just so blasted. It was "What is he doing over there?" I also live in a very remote place. It's not easy for people to get here. So, it's a real hassle to get ahold of me. It became real difficult because here I am spending the money and working on the record. And the label is saying "What is he doing?" I tried to tell them in the beginning that I wanted to do more vocals than two or three, but nobody really believed me. They had it fixed in their minds that I was the last instrumental artist on Windham Hill. The last couple of years at Windham Hill have been very transitional. I think that everyone is getting a little tired of them putting out wallpaper music.

Have you recorded any vocals prior to Door X?

I was in bands as a singer-guitarist-songwriter until 1980-81. So, there's a bunch of stuff. A lot of the stuff is hard to come by—stuff by the Special Interest Group and the Zobo Funn Band. The Zobo Funn Band was a big Northeast cult band. We had about a billion skirmishes with the big rock industry. Then I got real tired with the games that you had to play and the people you had to deal with in the late '70s. It was horrendous. All of the people we ran into at that time were just post-disco monsters. They were just monstrous, ugly people. I finally started to gig as just a guitar player. I started to get offers like Don Cherry tours and the ECM stuff with the Everyman Band, which started through Don. The last vocal group I have on tape is Nino and the Goddess of Love. That was a group I was in with two New Yorkers named Jill Gannon and Dave Orney, and the drummer from the Everyman Band, Michael Sukorsky. A very wild, totally punked out, bizarro band. It's hard to describe what it was.

Is any of this music still available?

The only album that you might be able to find through the grapevine is a really badly-produced Zobo Funn band record. I don't even think I have one. But they're still around. I'll be in Zurich or London and somebody will just bump into me and say "God, aren't you David Torn? Didn't you play lead guitar with the Zobo Funn band?" And I'll embarrassingly say "Yeah, it was me." So my background is this. And all of this other stuff has been kind of an experiment, you know? When you're dealing with music and your emotional state, everything seems like an experiment. So, to be honest, all of the records up to this point were way more experimental than Door X for me. Door X is me trying to get back to my roots and trying to integrate all of these things that I've learned in these other worlds for the past ten years into this thing that I enjoy doing, which is songwriting.

What does the lyric "Every mind has got to be defused" in "Time Bomb" relate to?

I get the impression from the crowd of people I hang around with that intellect is kind of a time bomb. And if that's what you're living by solely and you're not in touch with the emotional, expressive or sensual states, then that little bomb is going to explode. It can be great if the thing explodes, but sometimes it can leave a life in tatters. So, I guess that's what I meant. Every mind, at some point, has to get defused. You gotta get in touch with those stupid cliche phrases like "wake up and smell the roses" and shit like that.

What's the message behind "Diamond Mansions?"

Hopes get shattered many times in life, but there's always one more karat of hope. I think everybody has a set of hopes that are really beyond reproach. For the people that I know, I consider those to be "Diamond Mansions." It's a strange song, because it was one of the three songs that I wrote for the record on the way to the studio on a bridge over the Hudson River. It's very weird. "Time Bomb," "Door X" and "Diamond Mansions" were all written in my car, on the same bridge. I really like "Diamond Mansions." I'd really like to hear it on the radio. I know that it's been played a few times, but I haven't heard it yet.

Is it realistic to expect any of these songs to get significant airplay?

It should be once the record is really available. We're getting a fair amount of radio play. We hear "Voodoo Chile" and "Time Bomb" on commercial radio which is kinda great.

Is Windham Hill capable of generating a genuine hit single?

Windham Hill just doesn't have the money for that payola thing. I don't know how else the commercial stations pay attention to the new records that come in. We've had an image problem. As soon as they see Windham Hill, they put it into the New Age pile and never listen to it. Or the guy puts it on the Music from the Hearts of Hell Hour. And then he's so shocked he never listens to it again, instead of putting it into the rock pile where it belongs. Certainly, anyone who knows my name is not going to put the record into the rock pile. And when people put this stuff on their jazz shows it's also out the window. It's like "Forget this shit! What is this shit all about? Who is this guy? What kind of guitar playing is that? This isn't jazz!" So, we're trying to go through this sort of education process in the States. I think that it's real critical that Windham Hill try to get me involved in some kind of basic image-building, stupid-ass marketing thing, because that's the only way for the music to get across.

You've referred to your music as "arrogant ambient." Does that tag still hold for Door X?

I still think that it's pretty much that, yeah. It may be more arrogant than ambient at this point. But again, part of the musical success of this record or the personal satisfaction is that I've taken all of these things that I've been developing for years—all of this ambient shit—and it's in every single piece. It's like a new kind of psychedelia for me. There's a layering to each of the pieces. Even the most simple pieces, like "Time Bomb," have a layering of styles and idioms. There's even a layering arrangement-wise, with all of the strange things that I do on guitar. Every piece has these things that are constantly in motion underneath. And if you listen repeatedly and closely with headphones, you have the opportunity to hear something different in each piece of music. You can keep finding new little bits that make you think "What was that sound? Where did that come from?"

Those are qualities of most good music.

Outside of jazz and alternative rock, it's very rare. That quality of layering and there being many, many different levels to listen on. It's very unusual in the majority of things that are pop. Talk Talk's Spirit of Eden record is a good example. That is my favorite record of the past 15 years. Easily. It didn't really do too well on this continent. There's also Jane Siberry. Her stuff is more direct. I saw her live about three years ago in a little club on Queen Street in Toronto. That was an unbelievable experience. I bought her record The Walking and the one after that. Both of them are phenomenal albums for idiom breaking. It's not as deep as the Talk Talk stuff but still, they're on that list.

Speaking of idiom-breaking musicians, how did you and Bill Bruford hook up for the Cloud About Mercury sessions?

I think what happened was that I was looking for a drummer that could play many roles, and I had in mind either Jack DeJohnette or Michael DiPasqua on a hybrid electronic/acoustic kit. And DiPasqua was actually chosen to be the drummer. Then he quit playing. He decided that he was going to stop being a musician. So, I thought "Well, I should start looking into the rock field a little bit, huh?" The jazz guys are sometimes so phenomenally conservative. And I couldn't find anybody that I really dug. I didn't know anyone who was using electronics in the way that I had envisioned for that record. All of those pieces were based on drum tunings. I wanted to be able to play with somebody who could change their drum tuning from song to song, because I can't handle the sameness of normal drumkits from one piece of music to another. The drumkit always sounds the same. Sonically, that's real limiting. Then I was at my folk's house, and my mom was watching this video of King Crimson in concert. This must have been '81 or '82. I quickly started videotaping it. The thing that was really cool was the drum solo. I went "Wow, that's the cat!" So I wrote him a letter and sent him a tape. A week or two after that, I got a letter from him saying "Yeah, I'd really like to try something. I'm really interested in this whole ECM thing. I've heard about your work." And that's how that started.

How did the rest of the line-up evolve?

Originally, the album was going to feature a trio with me, Mick Karn and Bill. But Mick had a car accident while driving from Scotland to London where we were rehearsing. Mick was really interested in my music and ideas. But he never got to rehearsal because of the accident. So, Bill and I rehearsed alone for a day and a half which was great fun. He never wrote from the drumkit before as I was doing. He had thought about it but never had the opportunity to do it. So, we started to build all these tunings for these loosely-written pieces for which I had a melody, groove and sometimes a bass line. Then it turned out something happened in Mick's life and he just couldn't do the project. I really felt strapped, but Bill said "let's keep going man and get Tony." Tony [Levin] was supposed to originally be on my first album and he's my neighbor. So, we all learned some of the tunes. After listening to the rehearsal tapes, I decided there was too much guitar. So, I got in touch with Mark Isham. I didn't know him, but I knew his music. It seemed he would be a person to round out the group quite well.

The touring line-up was significantly different.

When we finally toured Europe, Mick was able to rejoin the band . It was me, Isham, Karn and Bruford. When we came to the States, Isham couldn't make it. So, we used a Canadian trumpet player named Michael White. He has a record coming out on CMP that I produced called Lonely Universe. He's a Torontonian and quite a good trumpet player. What ended up happening is Mick became Isham's favorite bass player. So, when Isham did his American and Canadian tour, he used me and my band. So, we started this whole crazy, little world. For instance, I had just done a David Sylvian record. So had Isham. When Sylvian went on the road, he wanted me and Mark because he had seen my band. It gets really incestuous. [laughs] What I'm trying to point out here is that the Cloud About Mercury thing was a crystallization of three or four different worlds which has resulted in a lot of cross-pollination between London, my little world in New York and this other world in Los Angeles. And to some degree, Canada too, in that I hired Mick Karn to play on Michael White's record. So, Cloud About Mercury, while it only sold about 40-50 thousand copies, may be a fairly important album.

Was there a concept behind the Cloud About Mercury album?

Cloud About Mercury was my poetic way of expressing my sensibility that nobody wants to admit that everything constantly changes. Things change, no matter what. Everything is in a state of transition, and yet some prefer not to see it. Mercury is an element that captures the essence of change. A cloud around it implies "Hey, it's there anyway, but if you want to put a cloud around it, that's what it is." In other words, things are changing anyway, but if you don't want to look at it, that's fine.

What happened to your relationship with ECM?

Too many psychological problems for one. Number two: lack of production control. Number three: lack of interest in selling the records from the executive's standpoint. Manfred [Eicher] is just a genius. He is ECM in every respect. Nothing happens without Manfred's direct approval or involvement. He produces just about every record. If he doesn't produce them, he says he does, like my last one. [laughs] He has a lot of control over everything at ECM and I felt that it wasn't going to go where I wanted it to go. I felt like I was never going to make a record like this. And I knew I wanted to. I wanted to be in a band. I wanted to rock. Everything was always airy at ECM. I felt like the ECM scene just wasn't for me. It was something that I fell into and it was really supportive while it was happening. But you can't be the same person all of the time. If you're going to be an artist, the whole thing has got to always be in motion. That label was a lot better for Bill Frisell than it was for me. The other side of it is that Manfred was always trying to squeeze me into his mode of thinking, which ended up being a lot like Frisell's mode of thinking. It's great to have the opportunity to do a record like Best Laid Plans, which will always be in print. The guy will never delete it. It's like a bit of history for me. And it was great to make those Everyman Band albums. It was great to make Cloud About Mercury too with that kind of support. But when you want to move forward, you want people to be able to at least understand what your vision of the future is. It just didn't feel like it was there at ECM. All my friends had left as well. So, I left too.

You use something called "hypnodrones" all over Door X.

Those are guitar loops. I got tired of not being credited with what I have done on other people's records, so I thought I would give it a cool name. I've been doing it since 1976, and it's on Best Laid Plans, the second Everyman Band Record and on every Isham film score I've ever been on in spades. All the Isham records too. It must be on the Garbarek records as well.

What was your role in the development of the TransTrem?

I called up Ned Steinberger around `80 or `81 and said "When you guys decide to build a guitar with a vibrato arm on it, let me know, because I love your guitars, and I would like to endorse them. But I won't do that until you start to work on a vibrato arm." He said "Very interesting. What would you want in a vibrato arm?" I said "I would like a vibrato arm that works like a bar that you use in your left hand on a pedal steel. One that works functionally like a slide, so that all the strings can move simultaneously in ratios so that this thing always stayed in tune as it was pulled up or down. Something that lets you change the shape by changing the pitch of some strings, but maybe not others." I may not be the only one who said this. Vernon Reid and others were involved a little bit too. So, every time Ned had a new version of it—we only live 30 miles from one another—I would go down there and say what I thought. I chose some of the pick-ups for that guitar. I have the first one. It's kinda cool.

I understand you aren't a fan of any of the early guitar synth implementations. Have you investigated any new ones?

No, that's a world that does not interest me. There was a point about two years ago where I decided to concentrate on sound processing on the straight guitar. But people still write in reviews that they think that I'm playing guitar synth. It pisses me off. At the same time, I must have achieved a sonic effect that's at least as broad as the guitar synth thing, yet I haven't sacrificed the expression. If you listen to some of the Holdsworth stuff, many people complain that he threw away his ability to emote using the guitar synths. I got the best of both worlds with a very simple and fairly cheap set-up. I get sounds that are really pretty unique and quite broad. I'm really very happy with it. I can still touch a string and hear its effect immediately.

You've become an in-demand producer. What are some of your recent and future projects?

I've produced two records for CMP. There's a Marty Fogel record called Many Bobbing Heads at Last. He was in the Everyman Band. Then there's the Michael White record Lonely Universe. My best, most outrageous guitar playing is on those two records. I'm also producing Karn's new record soon and Bruford's Earthworks record in January.

Earthworks is an underrated act. Their current North American tour is impressive.

This is their best tour to date. But I'm sad to say that they won't be back in America for a long time. Everybody who is in the "music between the cracks" world has been doing poorly. It's that way for everyone who isn't on a sponsored tour. It's so expensive to tour the States. The fees have not gone up in four or five years, so everybody is whining. The record companies are not willing to pay for touring, even though they want you to tour. Talk to Andy Summers, to Bruford, to Isham and everybody who has lost so much money in these last few years by going out on the road playing live. I seem to have hit the last wave of being able to do it and break even. We went out for four weeks with the Cloud About Mercury record in America and everybody really took it on the chin. The band took it as a band. No high fees were charged. We split everything, which is quite unusual these days. And still, personally, I lost about a couple of thousand dollars. That's not a whole lot, but I didn't make any money. It has just become harder and harder. It's a wacky business. It's like we're in a disco phase again. The stuff that's not mindless is getting pushed off to the side in the business. All of the creative people that I know of are in a battle to stay on top of it and not go under.