Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

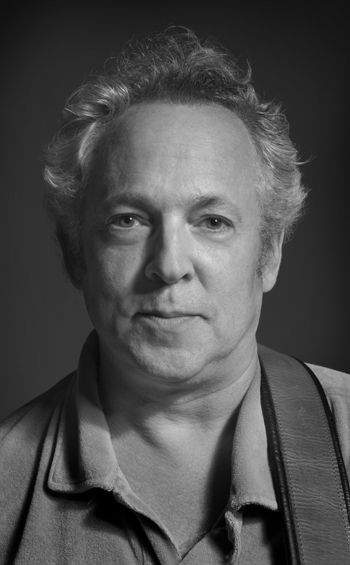

David Torn

Intersecting Ambitions

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2012 Anil Prasad.

The pursuit of a singular, yet multi-layered vision is a hallmark of David Torn’s creative process. It’s fundamental to his diverse discography that’s seen him stretch the boundaries of guitar beyond conventional limits. He’s a master of looping, processing and textures, but he’s also a virtuoso on the instrument in its naked form. Part and parcel of his artistic voice are expansive, cross-genre compositional leanings that manifest themselves on key albums including 2007’s Prezens, 2001’s Oah (released as Splattercell), 1995’s Tripping Over God, and 1987’s Cloud About Mercury. Listeners outside the avant music realm are also routinely exposed to Torn’s output via his work in the soundtrack and television advertising universes. The Order, The Wackness, Traffic, Three Kings and Reversal of Fortune are just a handful of his high profile film credits.

In addition to his continuing soundtrack and ad work, and planning a new studio album for the ECM label, Torn is currently gigging with several improvising bands, typically within the New York City downtown scene. He often plays with saxophonist Tim Berne, in addition to co-leading a trio with Berne and drummer Ches Smith called Goldfinger. Torn also has a duo with Bad Plus drummer Dave King. Torn, Berne, King, and Smith will also combine forces in 2012 to perform in a new quartet intriguingly named Ships is Slip When Sheeps is Sleep. Another group Torn performs with is Pink Tank, a trio with drummer Dean Sharp and trumpeter Russ Johnson.

Torn also took part in a recently released album titled Levin Torn White. It’s the result of a unique collaborative approach also featuring long-time musical partner bassist Tony Levin and Yes drummer Alan White in power trio mode. While that format might sound straightforward, the process through which the album was created was anything but. The musicians didn’t work together in the same room. Rather, they laid their parts down one at a time in a sequence that began with White, proceeded to Levin, then concluded with Torn. Producer Scott Schorr took the tracks in progress and architected and finessed them into compositions as they went along. The project took all three musicians out of their comfort zones, with the end result emerging as a compellingly fierce progressive fusion album.

Describe how you got involved with the Levin Torn White project.

I was sitting around my studio after finishing some Gatorade commercials and Tony called and said “Hey, I have this really weird project going on and I’d really like you to be involved. I don’t know any other guitar player who could be involved. Let me explain it to you.” He told me it was very likely that I wouldn’t really know what it would sound like until it was being mixed and that the process in general would be quite unusual. I asked a few questions about the business end and how long the project was going to take. Tony was very enthusiastic and sent me a few tracks in progress. They were just multiple drum cut-ups and Tony tracks that he played electric bass, upright bass, five-string cello, Stick, and other things on. I said “Wow, that sounds pretty cool. Okay, I’m in.”

Tell me about your creative process for engaging with the tracks you were sent.

They had already been cut and molded into a semblance of form by the producer Scott Schorr. Remember the band from Germany called Victory of the Better Man? It was like their process, but with a little more group involvement. What Victory of the Better Man would do is begin the process with one guy who starts a track, then sends it to another guy to work on. They would never get together. They might talk or they might not. Then it would go to the next guy and he would record whatever he wanted on it. This went on until the end and then they would mix it again. They called it “Victory of the Better Man” because it describes the origins of their process—let each guy do whatever he wants and at the end we’ll either hand it over to someone else to mix or just let ideas keep accruing later. With Levin Torn White, Scott decided the drummer would go first—that he would be the “better man” and cut his drum tracks into some kind of form. Those were sent to Tony Levin, who would play multiple, first spontaneous impression tracks to it. Tony and Scott were in the same room together and then Scott cut Tony’s tracks to Alan’s tracks. Next, Scott and Tony came to my studio and I put down a crapload of tracks myself. They weren’t organized—just spontaneous reactions. That was Scott’s directive from the beginning. Then he cut my stuff in, and finally, Tony Lash mixed it.

It was a unique situation for me because I was exploring a lot of spontaneous ideas and responding to the tracks without really learning them, except for a couple of small things that required memorization because they were rather complex rhythmically and harmonically. I felt I was putting down way too many tracks and that this would become a really complex process for somebody. [laughs] At some point, an offer was made for me to cut my own tracks myself. I passed on that because it seemed outside the range of the original directive and given that the other two guys didn’t get to cut their own tracks. I’m guessing I put down even more than Tony did. I was also composing the score to Jesus Henry Christ at the same time, so to dive headfirst into cutting the tracks, which I knew would have taken me six to eight weeks of daily work, wasn’t going to work schedule-wise.

However, there was one track that diverged from the process called “Sleeping Horse” that Alan doesn’t play on. Tony Levin suggested “Let’s have Torn improvise a complete piece on the spot.” So, Scott turns to me and says “Can you write a piece?” I said “Sure, when?” He said “We’ll go out and get some sandwiches. Why don’t you write a piece while we do that?” [laughs] I said “Really?” and he said “Yeah!” So, I started doing it and everyone ended up sitting in the room with me while I improvised the beginning of the piece. It was a very strange experience. The rule was “No drums. Let’s have something a little different here.” Tony Levin then took the piece and went back and put his first reactions down.

How much time did you spend recording your contributions?

I was in the studio with Tony Levin and Scott for two-and-a-half days. I played from 10 a.m. through lunch, then took a break and played until around 6:30 p.m. or so. I was playing the whole time. It was scary, frankly, because I was very careful to make sure I had something with melodic content for each piece—even though everything was improvised. I wanted to provide melodic content that could be focused on, because that was the one thing, form-wise, that was in the background. The idea was “Here’s a melody—something you can bend and repeat at certain points during the track.”

The record came out differently than I imagined it would. It’s loud and very, very aggressive in terms of the nature of its sound and musical noises. I didn’t know what to expect. I don’t think any of us did. But it does sound like the three of us from a perspective I had not entertained before. It came out in a surprising way for me and I really enjoyed the process. I’m not sure what I expected of myself when making it and it was a strange experience, but I feel good about it. It offers someone else’s view of what I did and it’s a good view of things. From a listener’s perspective, I enjoyed it very much. It’s an intense album and very far from my own current set of directions. I’ve been focusing on things like my improvised bands which have more of a sense of form that is intentional. The form is occurring spontaneously and we’re shaping it together. We have vocabularies for doing that in real time. Levin Torn White is not my record per se, or Tony’s or Alan’s. It’s our record and also Scott’s, who had a vision for what this band could and should sound like. That’s really key.

Give me a snapshot of the gear you used on Levin Torn White.

I mainly played electric guitars on it. I used my three primary guitars: a D’Pergo custom, a custom Saul Koll Tornado and a Teuffel Niwa. You’ll also hear some acoustic guitar on a couple of tracks and oud on another. I also used all kinds of looping, delay and wacky electronic devices. It was all done live and in real time, with no computer editing. There are some crazy pedals like a Paul Trombetta Design Tornita, Bone Machine and Mini-Bone. They were used a lot for getting grainy, intense sounds whether for noisy, harsh things or big textural things. I also used a bizarre pedal from Germany called the Hexe Revolver, which is a really strange sampling device. There are only five of them in the world.

Other than all of that, I used my regular stuff, including an Echoplex Digital Pro for stuttering and very long loops, and a Lexicon PCM-42 that’s modified to create very, very long delays. The reverbs were done live. The goal was to make up for the fact that I wasn’t with the other guys playing in the same room. So, some amount of spontaneity is required in order to get more of a band feel when doing the remote kinds of recordings we’re called on to do these last 10 years or so. I don’t use post-effects or editing too much when working this way. It’s a good philosophy if you’re trying to create the feeling of a band playing together.

Some consider Levin Torn White next of kin to BLUE with Tony, Bill Bruford and Chris Botti. Do you feel there’s a relationship?

There’s some of that type of BLUE energy certainly because me and Tony are involved. BLUE started out as Tony’s band and quickly became a “band band.” He declared it a band after we did the first record. He said “No, no. We called it Bruford Levin Upper Extremities, but it’s a band now. Equal say all the way across going forward.” God bless him for that. I thought that was one of the best bands I’ve ever been in. I really enjoyed it. But I don’t hear Levin Torn White the same way, except for some shared energy. Improvisation happened in BLUE, but there was composition and form that started with Tony and Bill writing, and then ended with me and Chris completely affecting things.

I look back on BLUE very fondly. It was a great band. Apparently, we were ramping up to a sudden demise, but it ended at the point where I felt “This is really great. I’m really enjoying myself. I’m free to do as I please within formats I really like.” It never went as far as it could have. I think we might have gone through a more improvisational period. Certainly, we kept that up in the live recordings people can hear. I think I would have been tasked with contributing to the writing around the time we ended. The same holds for Chris. BLUE could have been a fantastic outlet for him given he has a much more purposefully commercial direction with his other work. It could have been a way for the beautiful material he writes that wouldn’t necessarily be suitable for that pathway to come out. But things change. Do I wish it had continued? I do. Do I regret or feel terribly angry or bitter that it stopped? No. I have plenty of things to do in life. It just wasn’t meant to be.

What’s the status of your forthcoming ECM recording?

I’ve gone through a period of thinking really hard about what I want to do. Many things have been offered from Manfred Eicher’s side. He really, really wants me to do a solo guitar record with him in the studio. The reason we initially got together again is what he was excited about the hybrid, orchestral music I was writing. He was particularly interested in my film score for The Order. He tried to acquire that material for ECM. Also, there’s Prezens, the band. I love that band. It gets better and better and better. I’ve also been distracted by my film scoring career, which is a completely different direction very far from being avant-garde.

I recorded a whole bunch of short solo pieces that are unaffected—just guitar playing. I really like four or five of them a lot. They’re just very short minute-and-a-half to three-and-a-half minute things. It’s possible the next ECM project might be hybridized—some kind of orchestral material with some featured players and the potential for some solo guitar pieces in there as well. I want a way to incorporate the more formalized writing I’ve been doing in the film world into the material. I think I really need to challenge myself to best take advantage of the platform. It needs to be somewhat ambitious because recordings are things you save for posterity. I don’t want to make a record I’ve made before.

The Prezens band toured Europe, but a nationwide tour of the USA proved difficult to mount. Talk about the complexities of trying to make that happen.

It’s partially my own struggle working with players who are constantly busy. I’ll have three players who do very different things all the time like me and it can be daunting to put together a couple of dates. Usually, the finances of any single gig in the States are not broad enough to make it work. I can’t just say “Let’s play two nights in San Francisco.” We have to play other gigs in the same region. And then I start running into the incredible complexity of working musicians. The intersection of schedules can be very complex. I also have to be prepared to cover all losses. If we’re only playing one or two gigs that everyone is flying to, including bringing gear and staying in hotels, the reality is you’re kind of screwed. So, I have to do something reasonable and pragmatic. Ideally, we’d play three nights in San Francisco, one night in Santa Cruz, two nights in LA, and then one night in San Diego—things we can drive to, not fly to. Making even that happen in the States is challenging. Then I have to think about practical things like “Do we need a road manager?” Maybe, maybe not. If not, that means somebody has to book rental cars and hotels. In the end, it’s like running a small business and requires an incredible time commitment in preparation for a couple of one-off gigs. The Prezens band did two tours of Europe. I had help with an agent over there, but the States was difficult to mobilize.

What are your recent film projects of note?

One I feel really great about is Lars and the Real Girl. It took a lot for me to do that and it changed my film writing focus a lot. It was comprised of several small, contained pieces that were still spacious. It was a big one for me. Since then, I’ve done films like St. John of Las Vegas and The Line, which I both enjoyed. They were much more aggressive. I also did Teenage Paparazzi with Adrian Grenier. Other recent ones are Everything Must Go and Jesus Henry Christ which hasn’t come out. Lincoln Lawyer was another one that I did with Cliff Martinez. The Wackness is one other soundtrack that was a lot of fun to do.

Earlier, you mentioned you’ve done some commercial work for Gatorade. How active are you in that realm?

That was really cool because it was by invitation, which is the best way to work in that world. I’ve been writing spots since then. My son Elijah is a part of Massive Music, a music production company. He’s their Creative Director for North America and he’s instigated me writing several things since then. It’s a really different world and very tough, but I’m getting better at it. It’s very different than the long forms of writing I’m used to. I’m not thinking about a picture that lasts 90 minutes or a Torn piece that goes for 12 minutes. Instead, I have to think about 30 seconds or a minute. I have really enjoyed the process. The Gatorade gig went so well that they asked me to come back to do more.

I saw a Glee clip for Madonna’s “What it Feels Like For a Girl” that featured the backing track including a huge chunk of Cloud About Mercury. What’s it like to see your work in that context?

That was great, dude. I love that Madonna was so supportive when she found out her producer sampled me into the tune without telling anybody, with the result being that I received co-authorship of it—something we talked about in that book of yours. It’s still a peak kind of validation in my short life. That anyone would do that thinking they would get away with it in such a visible piece of music is amazing. What an unfortunate act of hubris on his part. Honestly, I really enjoyed the Glee thing. Part B of that enjoyment is “Okay, I’m getting paid.” [laughs]