Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

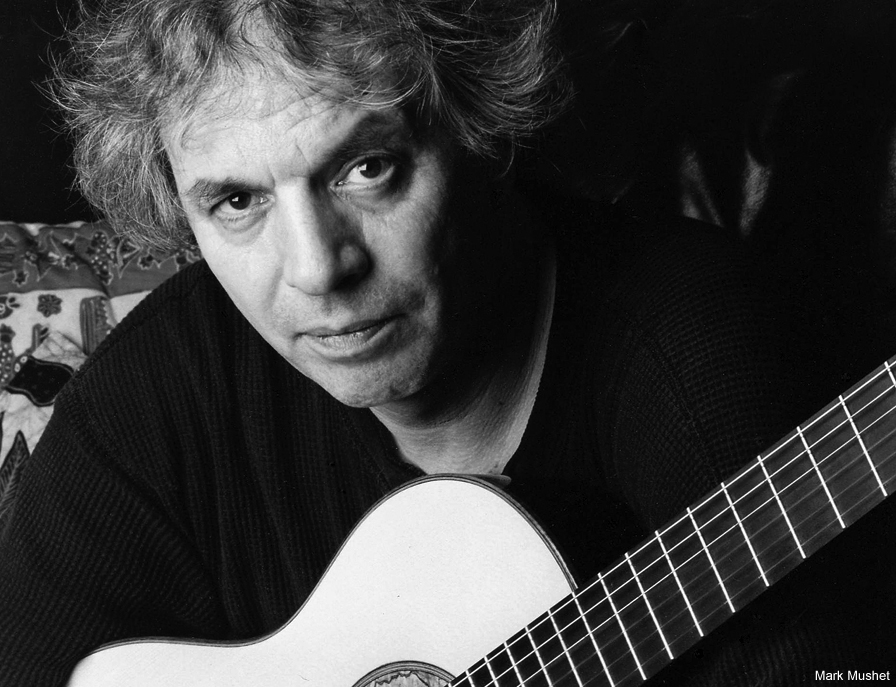

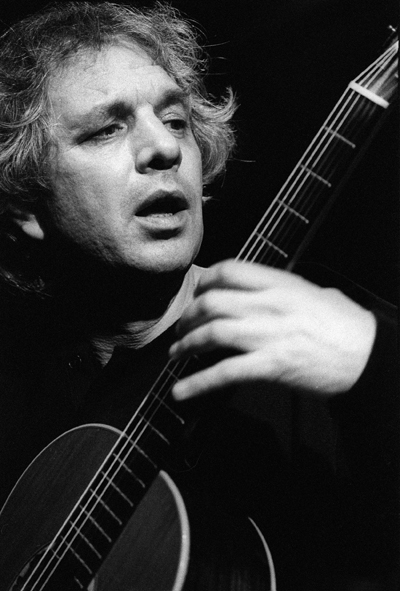

Ralph Towner

Unfolding Stories

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2000 Anil Prasad.

After four decades in the music industry, guitarist and composer Ralph Towner still maintains a childlike fascination with the muse.

“I feel the same way about music as I did when I was six years old—I’m immersed in it and everything is completely intuitive,” he explains. “I’m almost monkish. I can ignore my surroundings no matter where I am and just write music. I’m not thinking or calculating when I play really well, either. I’m a spectator along with the rest of the audience as it unfolds.”

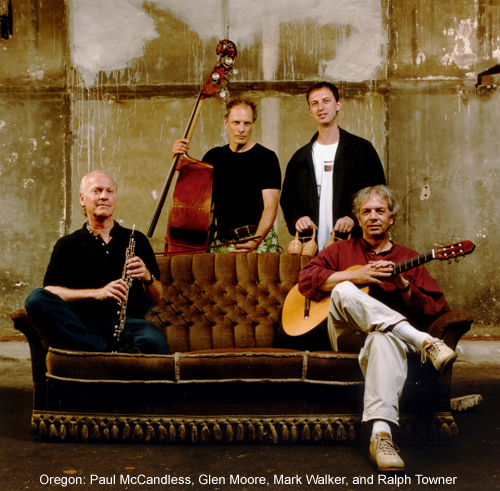

Towner is fortunate to be regularly surrounded by kindred musical spirits. Since 1970, he’s been the principal writer, guitarist and keyboardist for Oregon, a pioneering group that weaves world music, jazz and classical elements together. He co-founded the band with reedman Paul McCandless, bassist Glen Moore and percussionist/sitarist Collin Walcott. Since Walcott’s untimely passing in 1984, Mark Walker, and previously Trilok Gurtu, have been responsible for Oregon’s percussion duties. In 2000, the group released its 25th album, Oregon in Moscow, an orchestral recording that was one of its most ambitious efforts to date.

As a solo artist, Towner has been equally prolific. He’s released more than 20 albums on ECM that mostly feature quartet, trio and duo formations with John Abercrombie, Jack DeJohnette, Gary Peacock, and Eberhard Weber. For 1997’s Ana and 2001’s Anthem, Towner chose to focus entirely on solo classical and 12-string guitar pieces. Whether solo or in collaboration, Towner’s music often finds him pursuing a balance between composition and improvisation. And even when the scale tips to the latter, his approach is rarely anything but eloquent and evocative. The same can be said for Towner in conversation.

I understand you’re very pleased with how Anthem turned out.

I prepared very well for the disc. I’ve been stockpiling tunes for the record for about a year. And the sound is fantastic on the record, too. Also, this one seems to be more compositionally sound than others. The compositions are even more intricate and striking. I’m very happy with the collection of pieces—even more so than Ana, which was also very good. Ana was done in six hours, believe it or not. Also, on this one, I’m playing better. As usual, it’s 90 percent original tunes. Then there’s one by Scott LaFaro called "Gloria's Step," as well as a short version of "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" by Charlie Mingus. It has no overdubs. It’s like a live concert. We recorded it in the last days of February 2000 and mixed it on the first day of March, which was my 60th birthday. We had a little birthday party with Manfred Eicher and Jan Erik Kongshaug when we realized we’d been doing this for 25 years. That was incredible. There was a little disc-colored birthday cake. It was very nice.

The title track has a dual existence in that it also appears on Oregon in Moscow.

I’ve been playing "Anthem" in solo concerts in Europe for the past year and it gets received very well. It’s quite a striking piece. People seem to be very excited about it. So, we also did it with an orchestra for Oregon. "Anthem" almost sounds like a Russian work song. It’s a strange mixture of a Renaissance piece and a Profokiev march. I stumbled across it like all my pieces. There’s a small idea I recognize as a potential piece and it grows from there. I follow the atmosphere, the little spark, the catalyst, and these pieces grow like plants and all have their own identity.

The studio version of "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat" is much more concise than your live versions.

I had been performing it for a couple of years solo on 12-string guitar. During the performances, I almost played it on an epic scale by improvising on the tune and adding new blues sections and whatever I came up with spontaneously. But on the album, it just seemed more appropriate to just play the melody one time through. It feels like an homage to Charlie Mingus. I recorded it once before with Gary Burton in a duet 15 years ago. Gary was playing a festival and Mingus was there in his wheelchair. They had a conversation and he told Gary our version was his favorite version he had heard of "Goodbye Pork Pie Hat." That was kind of an endorsement for that piece from Mingus.

You’ve engaged in a great deal of collaborative work. How does that inform your solo approach?

I think it probably affects me quite a bit, compositionally. In general with collaborations, if I know in advance who I’ve elected to work with or use, I choose and compose pieces I feel will be flattering and work well with the other musicians in order to show them off in their best light. With a solo recording, you have to play everything yourself, of course. It can be even more difficult to compose enough material for solo guitar because it’s quite intricate to play all the parts. So, preparation is more difficult than for a group. Playing with people is another thing. For instance, Gary Peacock is wonderful. It’s the closest thing to playing solo. With Gary, you get the kind of freedom you have as a soloist because he’s so intuitive. When we play together, it’s almost as if it’s one instrument. He’s such a great bassist and a wonderful writer. In that collaboration, I’m the main melody instrument. It has been a wonderful testing ground that has served to improve my melodic playing. I feel I’ve learned a lot by playing duets and touring with Gary. I’m a lot more relaxed too. I’m not as hysterical when I play. It’s a maturing process, I think.

Are you still in search of new guitar techniques?

Well, there aren’t that many new techniques, but there might be some new effects you can discover. Most techniques on the existing instrument have pretty much been done and are tried and true. But honing them in your music is inexhaustible. You can’t really perfect that. There are slight shadings, dynamics and touches. So, it’s not that I’m looking for new techniques as much as trying to play the instrument as well as I possibly can. I’ve left a lot of room for improvement. [laughs]

You’ve said you’re trying to make the guitar sound like an orchestra. How does that idea manifest itself in your approach to the instrument?

In a sense, it’s vocabulary. The colors available to an orchestra are quite obvious with all the different instruments. The classical guitar has a tremendous variety of attacks and sounds built into it. My intention is to make people forget about the instrument when playing the music. If you play the instrument well enough, you draw attention away from the literal “Isn’t he a very good guitar player?” thing. You’re trying to transcend that kind of thinking in the audience and lure it into a sort of trip that explores the colors and beauty of the music going on, as well as the story that’s unfolding. And with all these colors that are available, it really is orchestrating—assigning parts to French horns here, trumpets there, and violins here. It’s the same with a chordal instrument like the guitar. You’re busy assigning colors, characters, shadings, and identities to different parts as you’re playing. You’re really telling a story, even though it’s in abstract terms, of what’s actually happening. It’s still an unfolding of events that occur in your memory. You remember the sounds and quality of the melody, as well as when it comes back and returns. The accompaniment and the inner voices are very critical, and the harmony is essential. Even with the simplest melody, you can add the most complex harmonies and give it an entirely different sense of mystery. It can be very aggressive-sounding or simple. There are infinite possibilities.

Have typical perceptions of what a guitar is capable of impeded its development?

Some people sort of succumb to that and play the most obvious things on the instrument that sound flashy. For example, speed is a very important color, but it’s just that. It’s also another device. It’s not just about playing fast. Every symphony orchestra player can play as fast as any guitar player because they have to—the parts have been written for hundreds of years requiring them to do so. It might be easy to limit yourself to what is most superficially attractive. But everyone, whether they are intellectually aware of it or not, has to play the way they have to in order to tell a story and relate to people’s attention spans, as well as their own. It’s an intuitive art when it’s done at its best. The greatest of the classical musicians are very intuitive as far as their sense of how an entire piece is developing and how they’re treating the weight of every phrase in their articulation.

How did the Oregon in Moscow orchestral project come about?

We had quite a bit of success with the previous Oregon record, Northwest Passage, and Intuition, our record company, actually made the suggestion that we do an orchestral record, which is unheard of. [laughs] We had a tight budget, but managed to do it in Moscow. It was a wonderful, great experience. We spent 10 days making it. It’s a really exciting record that was produced by Steve Rodby. We brought our own engineer and the equipment over there was okay, but it was in need of repair. So our engineer had to perform miracles to get everything working. It was a huge recording at a huge hall that could have housed a 300-piece orchestra.

The challenge was trying to get it all recorded in a short period of time. We had less than six recording days with musicians who hadn’t seen the music. So, we were working 10-hour days. They had to learn the material and it had to be sewn together as they learned it. For instance, the orchestra would learn the first 20 bars and then do that about eight times and one of those eight takes would be good. Then we’d proceed to the more difficult pieces. Some pieces were done straight through, but in general, the band worked very hard. We had a Russian conductor, so he was a stranger to the music. There was no English spoken by the orchestra, otherwise we could have brought our own conductor. That made it even more difficult. Communication was the main difficulty. But musically, everyone was very enthusiastic and very much into it. It was very challenging for them, but very inviting. They put in the extra effort.

Tell me about the process of putting material together for the sessions.

Some of the things I write tend to lend themselves very well towards orchestral music. An important element in my orchestral music is leaving the improvisational sections to the group and integrating them so it doesn’t sound like pop—like in one of those pops concerts where it’s just whole notes and everyone else sort of plays scales on top of it. This is real orchestral music.

We’ve been recording with orchestras since the very beginning in the '70s. We’ve played with the Philadelphia Orchestra and the Stuttgart Opera Orchestra, just to name a couple. The last time we did something with an orchestra was in Norway four years ago. At that point, we were between drummers and did two trio records and symphony concerts without drums.

We did all our own orchestration on Oregon in Moscow. Paul has three pieces, Glen has one and I have nine or 10. Half of it is stuff we’ve been playing since 1970. And there are pieces that have been written along the way since. For instance, there’s one long, complex piece I wrote in 1979 for the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra and have been playing since with different orchestras. There are quite a few new ones too that were written specifically for this record.

The interesting thing about our group is it always sounded like a miniature orchestra because we have the double reeds and often the percussion isn’t strictly jazz—although we have a lot of that too. So we fit in rather naturally with the orchestras. It’s really quite unusual for a group to have an in-house compositional staff trained to write for orchestra.

After decades together, what keeps Oregon fresh and interesting for you?

The reason we continue is strictly because the music keeps improving. If the music wasn’t good, we would have stopped quite awhile ago. In fact, the most critical junction in whether or not to continue came after the 1984 car accident we had in East Germany in which Collin Walcott was killed. The three of us who survived that spent the good part of the next year trying to regroup and decide whether or not to continue. We finally booked a really small tour for the three of us and realized we had to continue because the music was still growing and challenging. After 14 years, there was no reason to drop it. Then Trilok Gurtu came on board for seven years and things really altered with him.

How did Gurtu influence the group’s sound?

He’s an Indian drummer, but oddly, he was the most Western drummer we ever had. Even more so than Collin. He was more jazz and fusion oriented in his wonderful and complex rhythms. It was a really exciting period with Trilok, but it became a little more fusion, so things changed quite a bit with him. Now, with Mark Walker, we seem to have the best of all worlds somehow. He seems to be able to do everything and plays very musically. It’s a wonderful group ensemble concept he has, much like Collin did. We’re very happy with the way the group is going now as a quartet. Mark is so versatile. He’s a great jazz player and an absolute master at Cuban music. His whole perception of how to play with a symphony was perfect. He’s just a wonderful addition to Oregon. We’re on a real roll now.

Eyebrows were raised when Oregon chose to incorporate a more traditional drum kit into its sound with Walker. What made you go that route?

It depended totally on the musician, really. We needed someone who could play hand drums. And we’ve always been able to play jazz. In fact, I started in New York City as a piano player. It’s how I supported myself. I was a good second-call piano player and worked with Freddie Hubbard and different people. So, Oregon has always had the potential to play jazz, but with Collin, I think it would come out much differently. We couldn’t quite play the same time feeling. That was fine, because that was never our intention anyway. But with Mark, I can write and play new tunes that have that time feeling. It’s an additional thing we can do, but in general, most of the music is based on a more international kind of time feeling—some kind of combination that depends on the piece. Sometimes it’s more related to South American and Indian music and more unrelated to that swing feel. But we do play quite a few things that are jazz pieces.

All the material has to do with the complex harmonies that are grown from the jazz tradition and extended beyond that with complicated scales and chords. Plus there are simpler pieces, too. The nice thing about the group is we can do almost anything. This is a very thrilling group to be involved in. We can play everything from the 12-tone tradition to atonal-sounding music to polkas to tangos to anything else you’ve run across. We can somehow ingest it in some way and have it come out as something we’ve made our own. The thing about jazz is it always has that swing time feel. In a way, it’s got a limited kind of association when you hear it. It’s got a particular stance you have to have when you play it. When we do play jazz, I literally retool my approach to playing. I’m in a different world altogether. I just sort of retool for the rhythm feeling. It’s an interesting thing to accommodate the different kinds of time feelings we use.

How did Oregon approach rhythm during the years without a percussionist?

It was a little more on me. I tried to resist it, but I ended up playing a little too much. I became the drummer too and did a lot of percussive things on the guitar. In all the instruments, you have to be part drummer to play very well. It’s important to have a percussion concept when you’re playing. You have an internal rhythm that’s going on a meter, ticking away inside. You’re always making reference to that. The stronger you are with that, the more cohesive your playing is. You don’t need someone hitting you on the head with a drumstick to know where the time is. [laughs] Every musician basically internalizes rhythm. When you’re playing with a group, you find a happy medium between everyone’s internal senses of rhythm. It also depends on how well you play together and how well you can adjust to everyone’s unique sense of rhythm.

How has Oregon evolved from a personal relationship standpoint?

It’s a family. It’s very highly evolved somehow. An interesting thing happened when Collin was killed. All the areas Collin occupied, with his wonderful, stable personality and all the things he would take care of almost in unspoken ways settled out like water seeking a level amongst us. We all took on some portion of whatever Collin’s personality filled out in the group. That even included things like who does the accounting, who makes the call to find out if the hotel is booked and who drives the van. So, it was a very interesting sociological phenomenon about a group of people and how they relate and function as kind of a closed society with a sense of honor and without spoken rules. In a sense, my main duty is being the big composer of the group. I do most of the writing. In a funny way, I’m the musical director of the group. Without all the parts working together, the group wouldn’t function. It’s a kind of recipe for a small village. It’s not a bad example of how to get along. We give each other a lot of room.

We don’t see each other a lot when we’re not touring because since 1980, we’ve all left New York City. We were in New York for 14 years. That’s where the band really formed. It’s the last time we all lived in the same place. Since 1981, we all sort of scattered. Now I live in Palermo, Italy most of the time. Paul is in Bolinas, California; Glen lives in Portland; and Mark lives in New Jersey. So we don’t have a chance to hang out when we aren’t playing. We all have our individual careers and that is a big plus.

No-one’s tried to inhibit another’s individual aspirations. There’s a lot of generosity that way. The thing about it is it’s very serious and involved with the music when we do play. No-one’s doing it because it’s just a job. It’s a real, living thing and we still get very excited about it. After every concert, we talk about it. We’re excited about what we do. We always feel we have to do better. It’s a wonderful thing. It’s like an incredible kind of brotherhood. So, it’s a group that’s not going to disband. It would be like disbanding from your parents. [laughs] It’s truly a family, but not a restrictive or suffocating one. It’s a good model for relationships in that there’s a lot of respect and it’s very relaxed. It’s very unusual in that it’s really great people, not just musicians. They are wonderful people to hang out with.

Do Walcott’s ideas still influence the group somehow?

He was such an extraordinary person who was such a great friend. Even if he didn’t have a musical influence—which he does—it must be there somewhere, just having known a person that closely and having lost him like that. Your life is completely changed as a result of having known him. You can still remember things he said and how he’d react in a certain situation. So, this person is still alive in your life. People don’t cease to be part of your life when they die. There’s still so much that’s just naturally there—an inertia in someone’s life that carries on and lasts throughout the lives of everyone that knew him. In this case, he was such a rare person. He’s as much a part of the band as he ever was in some ways. It’s an interesting thing to know someone that well and have them influence your life and continue to.

Why did you relocate to Palermo?

I fell head over heels in love. That’s it. [laughs] I've been together with my wife Mariella Lo Sardo in Italy for eight years now.

How does living in Italy’s cultural climate affect your music?

I’m very happy now and that can’t hurt—to be really happy with the person you love. I’m really productive. I write a lot over there. I don’t hear the influence in the music so much, but it’s hard to know what is influencing me. I’m happy to have my little work space and I’ve had great runs of compositions. I’m really happy with a classical piano composition I wrote that was commissioned by WNYC. It’s a large, 20-minute sonato. It’s very difficult to play. Chris O’Riley played it at the premiere. I can’t play it—it’s too hard for me. It was really fun to write for a real virtuoso like that and not have to play it myself. I hope to have Chris record it for my next ECM album. I’ll probably also do something involving guitar and string quartet for it and have it come out as an ECM New Series record. So, I’ve been really prolific in Palermo. Sleepless in Seattle, prolific in Palermo. [laughs]

Do you feel Oregon has received its due as jazz pioneers?

No, I don’t think so. I really don’t. Obviously, it has from the people who follow us, but I think there could be a little larger audience than there is. But we’re difficult and disorganized when it comes to promotion. I’m a little slothful in that area. It’s difficult to manage and organize the group with different individuals who live in four distinctly different places. We can’t just do a gig at the spur of a moment. It costs a lot to get us from one place to another.

What’s your take on the industry climate you’re working in at the moment?

I don’t pay as much attention as I should to what’s going on. But it seems to me that the way the world is going with so many mergers means much fewer choices. If you went to a hardware store 20 years ago, you could choose between six or seven brands of screwdrivers. Now, there’s only one or two and they’re owned by the same company. Everything has been bought up and merged. In a strange way, things have happened with music categories too. Everything’s been shrunk down in a way. Also, I don’t think our music has been accessible on radio the way it used to be. It doesn’t get played as much. Music on radio seems almost retro as far as jazz goes. The new players are playing rehash—we call it "rebop." [laughs] So, for really unusual, experimental groups, there’s not a real commercial platform accessible to them.

People have to research to find this music. All this music exists, but you have to be an archeologist to dig it up. If you’re looking for new movements, I know the Scandinavian musicians are playing some of the most evolved jazz music I’ve heard. There are great virtuosos with wonderful writing there. So, you don’t always have to look to New York or America for something new. I heard some wonderful music from Italian groups who somehow incorporated a little bit of Naples and Mediterranean influences into the music—people like Enrico Rava that we don’t necessarily know in the States. So, as far as the marketing and what’s available to hear on radio, I think that’s become quite conservative in the last 10 years. There’s a little bit of a squeeze on us. I don’t know how often we’re being played in the States. But we have an audience and we established it a long time ago. It still grows by word of mouth. It’s a little slower, but that’s probably the best advertising you can have anyway.

Why do you think people are trapped in the “rebop” time warp?

I think it’s familiarity. I think it’s less risky and more secure. Look at television for example. The sitcoms are indistinguishable from one another. I don’t know if it’s a chicken and egg thing. I’m not sure if the makers of these things are determining the formats or if the formats are determined by the demand. They all claim it’s the demand. And the people who complain say it’s television itself. So it’s hard to know, really. So many people are involved and there is so much money at risk. It seems money is at the root of all evil. Quite often, when you throw money into music, you’re going to have tension because people’s jobs are at stake. Pretty soon it’s going to take a conservative line. Less risk is taken when it comes to things like profit. That’s what it’ll be totally judged by. It’s more of a risk to go out on a limb for something artistic or for something you like.

Why didn’t Oregon continue its relationship with ECM after Ecotopia?

We felt we needed a little more time. The ECM format is very intelligent, but it’s very demanding in that you have two days to do a record in most cases and then you have one day for mixing. We did that with the group and we have some great records on ECM. But we wanted to go and produce ourselves again and just have more time. I still like ECM’s approach though, because you have to be decisive. You can’t just sort of wallow around. You have to have it together and do it. We were able to do that. So, it wasn’t a violent split or anything. My heart is really with that company. There’s another person who’s like a brother: Manfred Eicher. We’re both from really small towns. We’ve known each other from the inception of the company. I first met Manfred in New York after Dave Holland introduced me. Dave and I were playing a concert and I heard about this record company. I eventually signed as a soloist with them, so I was one of the original guys with them in '72 or '73. The whole ideal of that company is incredible and it still maintains itself with all the pressure, nagging, weirdness, and petty jealousy of musicians, press and other companies. It’s amazing and incredible.

Elaborate on what you mean by petty jealousy.

Things like who gets more attention, promotion, money, and stuff like that. There’s also a lot of jealousy from other record companies because of Manfred’s success. The success is based on taking excellent musicians who are able to do records in a minimum amount of time. And the records start with pianos—gorgeous Steinways that are in tune. Jazz musicians used to make records with pianos out of tune. Even Bill Evans’ records have out-of-tune pianos. Some labels treat jazz musicians like second-class citizens. In contrast, ECM started with this incredible attention to musical detail and sound, and used the best-quality vinyl when making records, all with very low production costs. But the records would recoup almost immediately because there weren’t these ridiculous advances. You would always earn your advance back and your record would be in the black in less than a year. So, all the money was put into the quality of the recording, not spread over a bunch of confusing weeks and months.

ECM also does combinations of instruments that no-one ever dared to do in jazz where you typically had to have a whole band. Manfred was the originator of incredible duets like saxophone duets, and guitar and vibes. Manfred would also take great piano players and record them solo. Columbia and the big companies wouldn’t even think of getting near Chick Corea or Keith Jarrett with a 10-foot pole to do a solo record in those days. People forget who had the vision to do that and that’s how ECM started building itself. To this day, ECM records are done in a minimal amount of time. There’s an awareness of the advantage of doing things very well and very quickly, but with preparation and the best-quality recording techniques. It’s very idealistic and it has a real continuity in terms of the musicians.

I can speak for myself in being able to look at almost a life’s work on the same label. It also means each album is an evolution and exciting and means something. I’m not just making records to hear myself, but making recordings that show some sort of development. You owe that to your audience. Making a record should be the most exciting thing you do in your life. It used to be a big deal making a record. Sometimes people make records too soon these days, but that sounds like an old man’s grumbling. I’m glad I waited. I was 30 before I made a record. I had a late start. I didn’t play the guitar until I was 22 and dragged myself to Vienna, Austria where I started as a classical guitarist with a great professor. I started as a beginner. So, I’ve always been very late finding the right things I guess. But I’ve been developing a lot of different areas. It took awhile to be a steady composer at that time with the trumpet, piano and all the things I did. I didn’t always do them at the same time, but in blocks. But when I studied guitar, it’s all I did. I just locked myself in a room for two years. I condensed a whole boyhood and learned a lot in a short time.

I understand the album title Ana is a reference to your time with ECM.

Yeah. I think it’s a Latin name. It’s a reference to a collection of miscellaneous literary works. In a strange way, I often compare the ECM collection of works to a collection of authors’ works. It’s nice to have your entire history on one label. It’s quite unusual, especially to have it all still available. It’s still part of the wonderful, idealistic approach ECM has. And Manfred is a very literary person.

Reflect on making Together, Oregon’s 1976 collaboration with Elvin Jones.

Oh, that’s hilarious! That’s a great story. Elvin was signed to Vanguard Records. We were on Vanguard, too. Elvin heard us play and liked it and said he could hear himself in the music. Elvin suggested he do a record with Oregon. It was his idea. We got together and had to do it in one day. So, I thought “We better keep Elvin playing! We’ve got to go all the way non-stop and run him into the ground!” [laughs] We had a couple of pieces already written, so we started on those. Then I thought “Well, you guys improvise a duet. I gotta go write another piece.” So, I would run off to the corner and write the next piece while Collin and Elvin or Glen and Elvin were doing a duet or maybe the four of them were doing something without me. We kept this thing rolling until the end. I was worried “What if Elvin doesn’t break a sweat? Wouldn’t that be awful?” [laughs] But as soon as Elvin picked up a drumstick and went “bap” he started gushing and I thought “We’re okay now.” It was so much fun and we just had a great time. When it was all over, we went out and got sort of potted.

Then we had a photo session arranged for the album cover. The album cover was hilarious. What happened is we had a gig in upstate New York and we drove back down to the city and went to this photographer’s place. Elvin wasn’t there. Then pretty soon, we hear a ring on the buzzer down from the foyer of this building we were in. We went down and there was Elvin collapsed in the foyer. He had disappeared for four days in the city and gone on one of his famous binges. He was having what appeared to be a heart attack and was in a cold sweat. So, we called the ambulance and were tapping him and hoping he was okay. He went to the hospital and was okay in a couple of days. We visited him and then went back to the photographer’s studio as these sourpusses and had pictures taken of the four of us. So, what do they do? They put this picture of the four of us on the cover and put this big smiling picture of Elvin’s face on it like a sticker glued on top with these drumsticks around it. The art director was so bad. It just looked strange and like an afterthought. So, Elvin missed the photo session, but he was fine. That’s the story of that record. It was really a big jam session. It wasn’t a great recording. It was distorted, but the spirit was there. We had a great time with him.

You recently collaborated with Bill Bruford on If Summer Had Its Ghosts. What was that experience like?

Bill called me and wanted to do a trio with Eddie Gomez and myself. I thought it sounded interesting. I didn’t really know who he was. Then I heard some wonderful records he did with Django Bates from England with Earthworks. Those are really impressive. So, I said "I’ll do that." That’s how I got together with Bill. Bill wrote most of the music. I think I contributed one tune. I brushed up on a few of his chords, but it was basically his foray into the jazz world. It was a strange combination of people, but I had worked a lot with Eddie. Eddie’s been on several of my records. I’ve known him for years.

What do you make of Bruford as a jazz drummer?

Jazz is a strange thing. I think you really have to have played it a long time and been really involved in it to understand it. There’s something about the rhythm feel that’s not easy to learn. You have to really play it and have a history of working with it to have a jazz feeling somehow. I don’t know how much jazz he’d played up to that point. I think he was involved in more fusion-oriented things. He was with that big rock and roll band Yes. I never heard that aspect of him, but I imagine that was his strong suit. He’s such a gentleman. I can’t imagine him being a rock and roll drummer at all. But he had an idea of what he wanted to do and was very firm about it. So, that was definitely someone from another world—more than even playing with an Indian drummer for me. I relate more to Brazilian musicians than to English rock and roll guys. But I had rock and roll groups in high school. I used to stand up and play the piano and imitate rock and roll guys like Fats Domino and Little Richard.

Do you still have any passion for the rock form?

It’s not that much of a form. It’s not very complex. It was part of my life. It’s what I did. I dabbled a little in high school. I had a pretty normal American Graffiti childhood in Central Oregon and got off to a late start. As far as jazz went though, I played trumpet in Dixieland, polka and swing bands from the time I was seven or eight years old. I would improvise in my little school band during the concerts. [laughs] It was always during the school songs and marches. So, I could always improvise. That was my strong suit as far as jazz time feeling. It’s a tricky thing to get. You really have to play your way into it, I think.

What's your view on where things are going in terms of online music and artist compensation?

I really think if it’s somehow governed so the musicians aren’t ripped off by this medium too, it can be valuable. Let’s assume the royalties and payments for the music are settled and done right. That’s a big assumption. What it really offers is an accessibility to the music. The Internet could be the remedy for that—a way to have access to music you can only hear on a few public radio stations. That’s the excitement. But with so many possibilities, it’s almost a deluge. It’s almost too much. But for people willing to look, it’s going to be very successful in that way. Eventually, I don’t think we’ll even think twice about a five-second download of a whole album in perfect sound with an automatic connection to the proper royalty authorities. This could be a real boon and ear opener for people who want to hear a big variety of music.