Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Chris Squire

Propelling Forward

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2012 Anil Prasad.

Chris Squire, 2012 | Photo: Esoteric Recordings

Chris Squire, 2012 | Photo: Esoteric Recordings

Across its 44-year history, Yes has had six keyboardists, four lead singers, three guitarists, and two drummers. But it has only ever had one bassist: Chris Squire. The pioneering musician, known for his melodic, driving rhythms and harmonic work, has remained determined to propel the band forward as it scaled the peaks of commercial success, as well as during its most challenging periods.

It’s accurate to say Yes’ recent existence has fallen into the latter category. The group’s original lead vocalist and co-founder Jon Anderson exited in 2008 due to respiratory issues. The act went on to recruit replacement singer Benoît David later that year. The fact that David was from a Yes tribute band named Close to the Edge, found from watching a YouTube video, proved controversial, but he was eventually accepted by the fanbase and settled into the demanding role. David also sang on Yes’ latest studio album, 2011’s Fly From Here. The Trevor Horn-produced release proved to be the band’s biggest-selling recording since 1994’s Talk.

To everyone’s surprise, David left Yes in early 2012 for health and personal reasons in the middle of the group’s unexpected critical and commercial renaissance. Without pause, the band brought Jon Davison, lead singer of Glass Hammer and another Yes tribute band called Roundabout, into the fold. The Fly From Here tour continued in 2012, with Davison cementing his role in the group.

In addition to presiding over Yes lineup changes, Squire recently released an album under the band name Squackett titled A Life Within a Day. It’s a collaboration with ex-Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett and producer-keyboardist Roger King. The disc offers up a set of melodic, accessible songs, full of lush harmony vocals and addictive hooks. It’s sophisticated, art-pop effort inspired by the late-‘60s psychedelic era.

Innerviews called Squire during the Philadelphia stop of the Fly From Here tour. The Ritz-Carlton hotel receptionist had to be assured his pseudonym "Hugh Valways" was real before agreeing to put the call through.

That’s an amusing alias. Do you still have fans chasing you into hotels these days?

[laughs] No, there aren’t as many of those as there used to be. We’re just used to having pseudonyms on tour after all these years.

Yes, 2011: Benoît David, Alan White, Geoff Downes, Chris Squire, and Steve Howe | Photo: Frontiers Records

Yes, 2011: Benoît David, Alan White, Geoff Downes, Chris Squire, and Steve Howe | Photo: Frontiers Records

Detail what led to Benoît David’s departure from Yes.

It wasn’t really suiting his lifestyle to be away from his home in Montreal. He had issues at home he had to deal with. He was often away when things came up with his teenage sons. So, it was a combination of various things that made him decide this wasn’t really the life for him. Benoît did a great job and sang very well on the Fly From Here album. Trevor Horn was happy with his vocals. But I guess Benoît’s heart just wasn’t into being the lead singer for Yes, for whatever reason. So, we moved on and thankfully found Jon Davison who is fantastic. He’s a really good singer and his heart is definitely into it.

Apart from being able to replicate Jon Anderson’s sound, what qualities made Jon Davison the right guy for the gig?

The one thing Jon Davison has over Benoît is that he’s also a writer. We’ve started looking at possibilities for material for an album which we will probably record sometime in 2013. That’s definitely a plus in Jon Davison’s column. Any new member that comes into Yes that contributes as a writer is always valuable. Yes is an evolving thing. It’s going to evolve further with Jon Davison’s input.

Fly From Here was based on a lot of historical material. Will the next Yes album focus on newly-written material?

Yes, I would imagine. There will be a slightly different concept. On Fly From Here, there was a desire on Trevor Horn’s part—as well as myself and Steve Howe—to revive the song “We Can Fly From Here.” It was music we hadn’t finished during the Drama era. We went in with the idea of evolving that material which wasn’t fully developed, previously. I think the next album will be totally fresh and new. We’re hoping to work with Trevor again. I enjoy working with him a lot. I hope he’ll have the time to fit it in. He has quite a busy schedule.

Yes’ record label Frontiers proved highly effective in making Fly From Here a commercial success. After years of label issues, that must have been gratifying for the band.

I give Frontiers kudos for being able to do that. It was also a very good album, which means a lot too. We got a lot of critical acclaim from the British press. Many of the classic rock and prog-rock magazines put it in their top-10 best albums of 2011, so it got a lot of people’s attention.

An interesting thing about Fly From Here selling well is it seemed to be largely absent of any commercial element.

Yeah, it wasn’t aimed at trying to get an “Owner of a Lonely Heart, Part II” out there. I’m not opposed to commerciality. If one is lucky enough to come up with something that becomes enjoyed in a widespread way, that’s not a bad thing.

What sort of pressure was the band under when it made Fly From Here? The stakes were high with a new lead singer and record label.

There’s a certain amount of pressure involved with making any Yes album. We ended up with a team that included the return of Geoff Downes and Trevor Horn. All of us always got on well as a group, so we had a pretty good time making the album. There wasn’t a lot of pressure on anyone there, other than time pressure, and the usual financial constraints of having to stick to a budget.

Bands like Kiss and Aerosmith still manage to play arenas, mostly playing their back catalog. Why has Yes had issues with shrinking audiences, despite having sold more than 30 million albums?

In the case of Kiss, you’re dealing with a comic book fantasy. It’s almost like The Simpsons being the biggest sitcom ever. People identify with that timelessness and the idea of characters never getting old. With the makeup, Kiss can be seen that way as well. There’s some kind of human nature thing about being attracted to that sort of comic book longevity. All power to Kiss for coming up with the concept and sticking with it. The fact that they still have these audiences probably has to do with them padding the bill with people who draw audiences as well. For Yes, sometimes we have a bigger album and get bigger audiences. The Fly From Here tour went very well and everything was sold out or almost sold out. We’re doing pretty well.

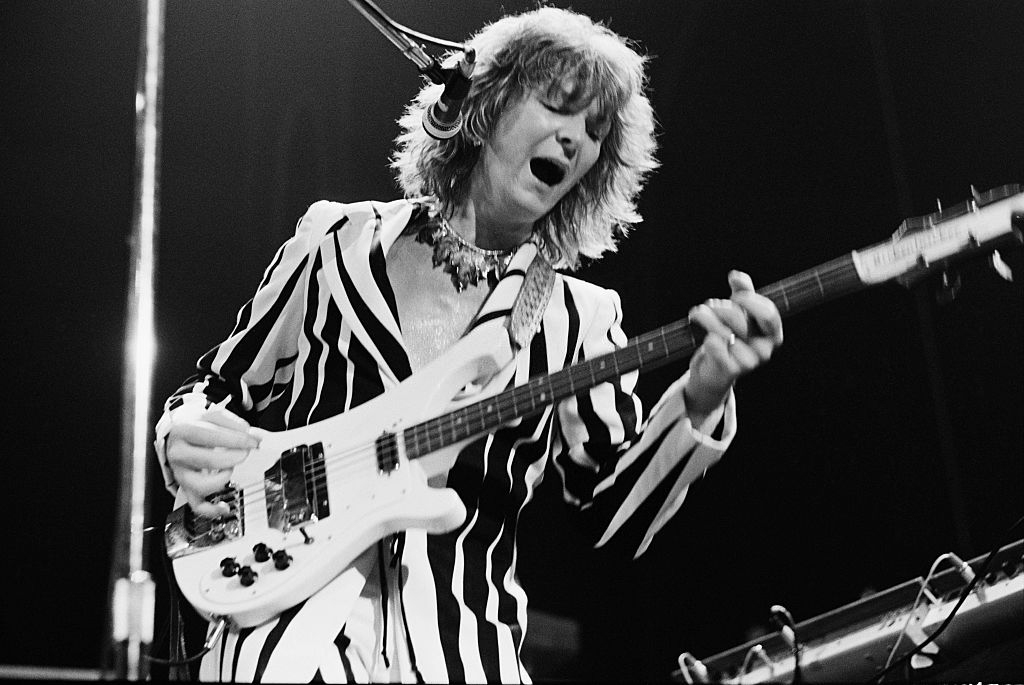

Chris Squire, 1977 | Photo: Atlantic Records

Chris Squire, 1977 | Photo: Atlantic Records

Do you hold out hope that things could catch fire in a big way again?

One always likes a shot in the arm to happen. How that happens is a little indefinable, otherwise everyone would be doing it all the time. [laughs] It’s just down to making an album that captures people’s imaginations and catches more of the fringe fan base, as opposed to the hardcore people who will like pretty much anything we do. We do have good audiences, and recently I’ve noticed there are a lot of young people, including teenagers, in the crowd. That’s always a healthy sign.

Tell me about your signal path for the Fly From Here tour.

I use my Rickenbacker 4001, Mouradian CS-74, a custom triple-neck, as well as a custom Tobias 4-string. I’m also using a 100-watt Marshall Super Bass head, two Ampeg SVT 2 pro amps, Marshall 4x12s, and two Ampeg 8x10 cabinets. In addition, I run bass pedal samples through a SWR 400-watt bass amp head.

Yes fans have demanding expectations of the group. What’s your approach in terms of considering their feedback?

I have a slightly cautious point of view when it comes to reading fan input. There are a lot of people who love this and that, and sometimes I think the opinions are a bit off and sometimes I think they’re good. I take the feedback with a pinch of salt.

You once told Yes fans “Sick and tired of reading crap…Go rest! Take your children on a picnic. Sit outside a bit longer and enjoy the now” when there was an uproar about the impending replacement of Jon Anderson.

[laughs] I could well have said that, yeah. There is a small section of people who take things too seriously, but that’s going to be the same for any band or performer. At the end of the day, when we’re making music, we’re really making it for ourselves. It’s a bunch of guys making music in a room with the object of coming up with something we all enjoy. When it leaves the room, it goes out into the wider population, and hopefully, it captures the imagination of the listeners out there.

Yes, 1984: Alan White, Jon Anderson, Chris Squire, Tony Kaye, and Trevor Rabin | Photo: Atco Records

Yes, 1984: Alan White, Jon Anderson, Chris Squire, Tony Kaye, and Trevor Rabin | Photo: Atco Records

90125 is 30 years old in 2013. How do you look back at that era of the band?

I haven’t thought about the anniversary, but celebrating it is something worth thinking about. We don’t have any definitive plans. That was a very good era for Yes. It was a very commercially successful record. We did quite a bit of touring on the back of it and made quite a bit of money. Generally, things were more on the positive side. We had a lot of great, enjoyable shows at that time with the Trevor Rabin lineup. I remember Madison Square Garden in 1984, when after the second song “Hold On,” the audience applause went on for 15 minutes before we could start the third song. It was an extraordinary event that sticks in my memory as a particular high from that era.

Describe the seeds of Squackett.

I first met Steve in Brazil in the ‘80s. It was just “Hi, how are you?” Apart from that, I didn’t have any real contact with him. I don’t think Yes ever played a show with Genesis on the same bill in the ‘70s. It wasn’t until 2007 when I was doing my Swiss Choir album in London that we really connected. I needed a guitarist and our drummer, Jeremy Stacey, suggested giving Steve a call. I did and Steve got involved. He did a great job. Our relationship got off to a really good start. After he played on my album, I said “Can I play on anything for you? Do you need help with demos or anything?” From there, I played on a few things he was preparing for future projects. During the course of that, it became a natural thing for me to work on his music and for me to play him things I had been writing. One day, it occurred to us that we should just do an album together. [laughs] We carried on in that direction, writing together, and it was a simple and easy process, with no stress involved. There were no record companies with deadlines. One day, we had an album ready. We had to wait a little while to release it because Steve had some legal things to sort out in his life. We also wanted to find a good record company to release it. We went with Cherry Red’s Esoteric label. I’m really glad the album is out now.

What is it about the chemistry that makes the collaboration work?

We get on really well as people and enjoy each other’s sense of humor, which is a bonus. It was an organic thing. Steve had some songs he had written that he wanted to record. I had some too. We chose the material we both liked and it was a painless process. We would usually go out somewhere for dinner after working in the studio during the day. It was actually my wife who came up with the name “Squackett.” Restaurants would ask for a reservation name when we all went out together and she would just say “Oh, it’s Squackett.” For some reason, that stuck as the name of the band. [laughs] There is a nice chemistry with Steve and his wife, and me and my wife. We’re all good friends.

We mustn’t forget the third member of the Squackett team, Roger King, who has been working with Steve for many years as a production cohort and writer. He was involved in the keyboard parts and production of the album very much. We all got along really well.

After working on Yes’ Fly From Here at Trevor Horn’s studio, was it novel to work in Hackett’s living room when recording Squackett?

It’s not a strange concept for me. I’ve done that in my own places of residence over the last 20 years. We didn’t need to be in a studio to do vocals, because these days it’s pretty much all done into a computer console, so we did quite a bit in his living room. It added to the relaxed nature of the project. Steve also has a studio in Twickenham, so we recorded my bass parts there.

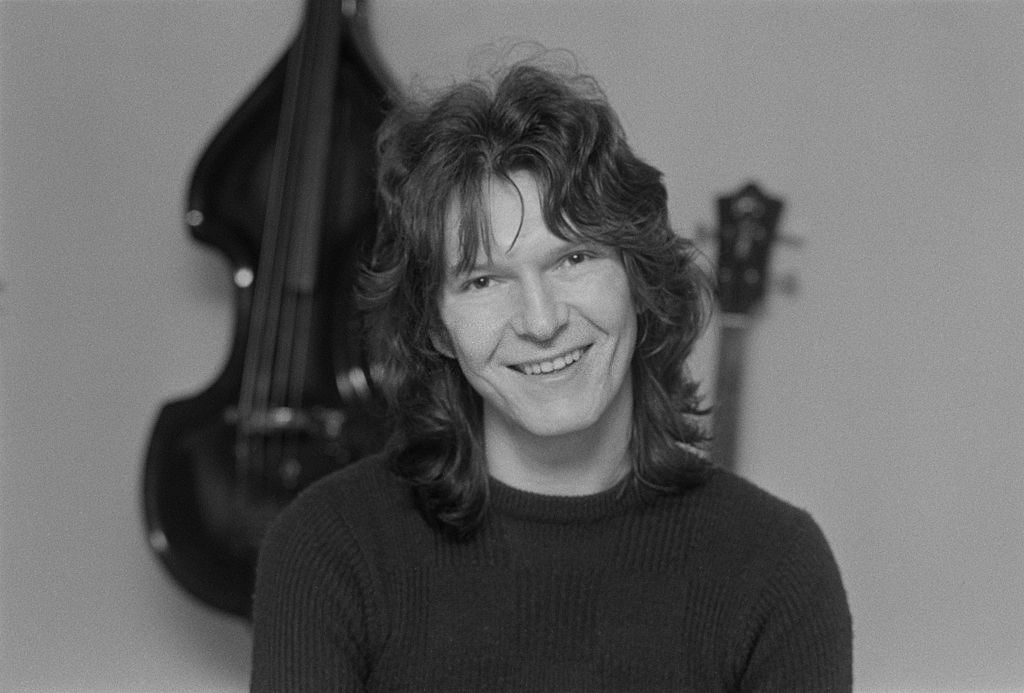

Steve Hackett and Chris Squire, 2012 | Photo: Esoteric Recordings

Steve Hackett and Chris Squire, 2012 | Photo: Esoteric Recordings

What basses did you use on Squackett?

I used my Rickenbacker 4001 on most of the tracks because Steve wanted the authentic Chris Squire sound. The album features me playing one-note, straightforward bass lines on it, apart from a little bit of chordal work on the song “A Life Within a Day,” which I did on my Mouradian CS-74. The Mouradian has been a favorite of mine over the years, and a bass I’ve had since the ‘70s. It’s a very good-sounding instrument. A Yamaha representative also brought a new bass guitar down to the studio. I tried it out and played a couple of riffs that developed into “Tall Ships.” I can’t remember what the bass is called, but it’s a Jetsons-like, pointy blue-and-red instrument with lights underneath the volume and tone controls.

Do you feel your bass approach continues evolving over the years?

I think so. Yes has been pretty active as a live act since 2008. A lot of technique development purely arises from playing live. The way I pluck the strings has evolved. I use a pick a lot, and the way I hold it is slightly different from when I started. Now, when I strike a string, the pick hits the string first, then a millisecond later, the side of my thumb plays the same note. So, you get the hardness of the attack of the pick, and the roundness of the sustain that comes from the thumb. It’s a technique that’s naturally developed without even thinking about it over a period of years. It’s a more mature sound compared to when I was younger. As far as my left hand technique is concerned, it’s pretty much the same as ever.

You play on Billy Sherwood’s new Songs of the Century Supertramp tribute and Prog Collective albums. Tell me about the rekindling of that collaboration.

Billy and I have worked together a lot over the years. We didn’t for awhile because I moved away from Los Angeles to London for a few years. Because of geography, we had a break from each other. Now, I live in Phoenix, Arizona. We’re relatively close again, so we get together from time to time to do various things. Prog Collective is something Billy was at the helm of. It’s a concept Billy and the record label Cleopatra had, which was to have him go around and see how many prog musicians he can collect to play on various things. [laughs] That’s as much as I know about that.

Are you a Supertramp fan?

No. It’s just that Billy was involved in that project and I was visiting him at his studio in his house when he was working on it. We spent a few hours messing around in there. I sung on an original song that was a Supertramp sound-alike that Billy wrote called “Let the World Revolve.” It was all done quite quickly.

Roger Hodgson was rumored to be considered for the Yes lead vocal slot when Jon Anderson left for Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe in the late ‘80s.

It wasn’t so much to be the lead singer of Yes, but a different project. Whether that would have evolved into Yes at some point, I don’t know. We weren’t looking for it to be Yes. Roger is a friend of mine. The band would have been Roger, Trevor Rabin, Alan White, and myself. I stayed at Roger’s house in Northern California once for a few weeks and worked on some material. It was one of those things that fizzled out and didn’t go anywhere. “Walls,” one of the collaborations with Trevor and Alan, ended up on the Talk album.

Chris Squire, 1974 | Photo: Atlantic Records

Chris Squire, 1974 | Photo: Atlantic Records

You’re currently working on an autobiography. What can you tell me about it?

I’m working on it with my friend Vincent Gallo, who is best known in the film industry. I’m doing interviews with him and we’re recording them. Vince and I have been good friends for years. He’s the godfather of my son. He’s a huge music fan and Yes fan. He used “Heart of the Sunrise” in Buffalo ‘66 and “Sweetness” during the credits. Right now, the interviews involve me just remembering stuff about my life. I think the project will take a couple of years. We’ll see how it ends up.

You’ve also been recently speaking about bringing Yes to Broadway for an extended run of gigs.

It’s being talked about, but is on the back burner while we mull it over. The idea is to do a history of Yes concept, including past and present members, if it was physically and financially possible. That’s loosely the idea that’s being discussed. We were looking at Broadway as opposed to Las Vegas or Atlantic City, which is where people try to do residencies. Those cities work for some acts and don’t for others. So, we put this idea out there to see if someone who controls the theaters on Broadway would come to us and suggest something. We’ve had a couple of enquiries, but it hasn’t gone that far. We’re still promoting Fly From Here and that’s going to take care of this year. Next year, we’ll be looking at doing a new studio album with Jon Davison. So, this idea may not surface for awhile.

Many people identify the spiritual side of Yes with Jon Anderson. Do you feel Fly From Here embraced that element?

Steve Howe and myself have also been writers along with Jon Anderson. Maybe Jon Anderson wrote more of the spiritual stuff, but I don’t think our writing doesn’t contain that element. Songs mean something different to each listener in terms of what they take away from the lyrics. It’s hard to define what the level of spirituality is between one song and the next. You have to also add Jon Davison into the mix. He has ideas. We’ll see how it comes out in the wash.

Does spirituality inform your life?

I know people who actually put time aside during the day to meditate. I kind of do the same thing, usually when I’m in the shower. [laughs] I don’t attach any religious beliefs to meditation. I just think about things and you can call that meditating. I do some of my best thinking when I’m having a shower.

You and Rick Wakeman have talked about the idea of Yes continuing beyond your lifetimes. Is rebooting the band with younger players a serious consideration?

Yeah, it’s possible. The London Symphony Orchestra is hundreds of years old. I recently began to think that there could be a Yes in 100-200 years time. Unless there is some amazing, modern medical breakthrough, I doubt I’ll still be in it. [laughs] So, the concept of people coming in and carrying on in the Yes tradition is definitely an idea. It’s not something I spend a lot of time thinking about. It’s just the natural progression of Yes. The fact that there’s still a Yes after 44 years has led to that idea. I remember when I was young, I used to see these soul bands that wouldn’t have any of the original members, but they’d still be touring. That’s something that could apply to Yes and other rock bands as well.

Listen to the audio podcast version of the interview: