Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Joe Zawinul

Man of the People

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1997 Anil Prasad.

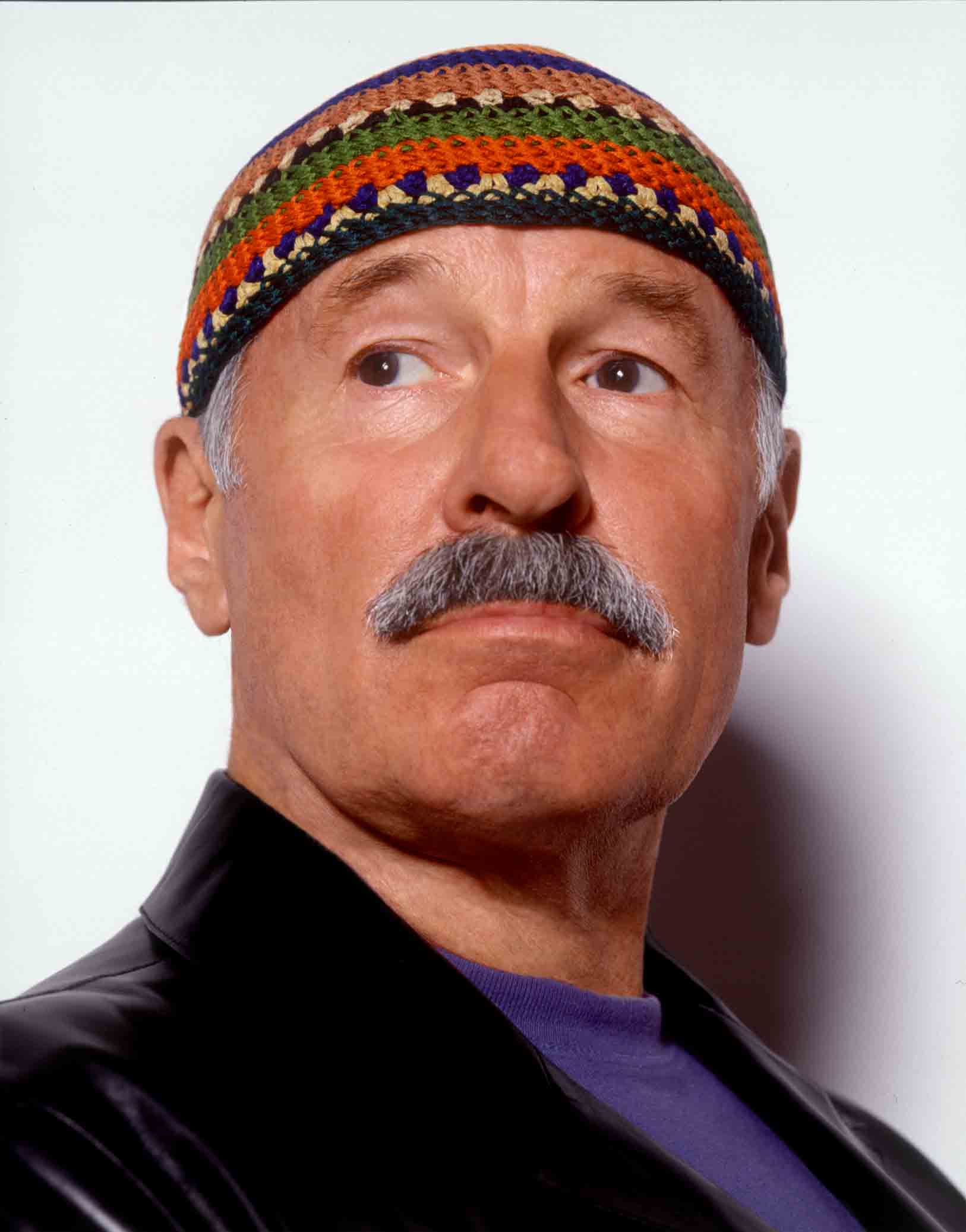

Joe Zawinul at his home studio in Malibu, CA | Photo: BHM Productions

Joe Zawinul at his home studio in Malibu, CA | Photo: BHM Productions

Technology pundits tell us we live in a wired world that enables people to bridge continents with the click of a mouse or remote control. But some critics believe the world is experiencing unprecedented levels of fragmentation across social, cultural and political lines. Are the tribes of the world pulling further apart or coming closer together?

Joe Zawinul advocated the latter answer. It’s a viewpoint the pioneering keyboardist—who helped establish electric piano and synthesizers in the popular music pantheon—expounded on in his 1996 release My People. The upbeat and spirited disc seamlessly weaves together world music, jazz and rock elements to make its point. The album features a cast of 32 musicians from across the planet, including Salif Keita, Burhan Öçal, Alex Acuña, and Trilok Gurtu.

Bridging cultures and influences is something Zawinul did throughout his career. During the '60s, he worked with jazz luminaries such as Dinah Washington, Ben Webster and Cannonball Adderley. Landmark collaborations with Miles Davis followed on the trumpeter’s 1969 releases In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew. The discs helped spark the jazz-rock movement and established Zawinul as a composer and visionary to be reckoned with. From 1970 to 1986, he co-led Weather Report with saxophonist Wayne Shorter. The forward-looking fusion band incorporated world music rhythms and structures into its sound throughout its reign as one of the most celebrated jazz acts of all time.

Perhaps the greatest realization of Zawinul’s global musical perspective was via The Zawinul Syndicate, the post-Weather Report group he led from 1988 until his death in 2007 from skin cancer. The band’s ever-shifting roster featured top-flight players from the four corners of the earth. Together, they forged a highly individual world fusion sound that was both complex and accessible, with the deepest grooves imaginable. The group’s last line-up, featuring drummer Paco Sery, bassist Linley Marthe, vocalist Sabine Kabongo, guitarist Alegre Corrêa, and percussionist Jorge Bezerra, was among its most potent. A fiery performance was released on 75, a posthumous album that captured the band performing on Zawinul’s 75th birthday in Lugano, Switzerland, two months before he passed away.

Several Zawinul Syndicate alumni were featured on My People, as well as Stories of the Danube, a large-scale symphonic project also released in 1996. Recorded with the Czech State Philharmonic Orchestra, the album explored the Austrian-born musician’s Hungarian, Czech and Sinti roots. The disc is an aural journey through the historical drama and trauma associated with the Danube River and the numerous countries it streams through. It also serves as a poignant reflection on the many struggles Zawinul faced during a childhood shadowed by World War II. It’s an ambitious effort that further underscored his lifelong commitment to using music as an expansive storytelling vehicle.

Photo: ESC Records

Photo: ESC Records

Describe the message you wrote My People to convey.

It’s more philosophy than music. There’s a real communication within all of us and so many people deny their own thing. I always believed in the fact that the world is one thing. Even when I was a kid during wartime, I always believed in the humanity of the people of the world. I’m talking about all kinds of people. I grew up with that idea of many tribes. I believe that all people are great in every nation. I’ve been all over the world and I consider all of these people to be my people.

I heard an interview on CBC Radio in Canada with Duke Ellington and he talked about the idea of “my people” and I thought he made the same statement I’ve been making throughout my entire life. Duke is really one of my favorites. He made a great impact on my life. So I said to myself, “that’s what I want to express” and I decided one day to make a record about that. Therefore, I have many people from many tribes singing on the record. My favorite instrument is the voice when it’s used right, but it can be the absolute worst when it’s not. In every culture, there are a handful of really outstanding storytellers. That’s what it is all about—music is nothing else. Music is not a bunch of notes and chords. Music is storytelling.

How did the pieces on My People come together?

My people are the people. They’re everywhere on the planet. My people are not just Austrians or white people. It seems to me that when anybody talks about “my people” it’s about people who are of their race or nationality. I wish people could get away from this concept so we can look at ourselves as all being from out of one pot. It was something I wanted to say for a long time. So, the pieces were very easy to put together when I explained the concept to the other musicians. By the time I had the pieces together, I was trying to find the best people to interpret them—especially the piece called “Bimoya.” I wrote that seven years ago as an instrumental and then I realized I wanted Salif Keita to sing it. Salif and I are good friends. I took the tapes to Paris and recorded Salif and then I went to Switzerland to work with Burhan Öçal. Then I went to Austria and recorded the yodelers. I used to live in Malibu before moving to New York. While I was in Malibu, I recorded friends like Alex Acuña. That’s the way I got it all together.

How did you choose the combination of musicians that appear on My People?

I come from sound. I need sound to make music. Everybody does, but some less than others. I'm totally depending on sound and if I have a piece of music, I need the right interpreter to make the piece come off. This is the premise for me—to find the people so I can express the music correctly. Sometimes you never have the opportunity to have the best musicians, but I always have the best musicians, although sometimes I can’t get them all together at one time.

Is it ever a challenge to make so many world musics fit together?

No. I’ve been doing this all my life, man. I played the accordion when I was a kid and I took a similar approach. There’s no big difference. But it took a long time for people to understand what I’ve been responsible for. You know hip-hop? I invented the beat of hip-hop! In 1970, I invented it and no drummer could play it. I did an album with Weather Report called Sweetnighter that has a track called “125th Street Congress.” It has the original hip-hop beat. I have about 50 recordings of rap and hip-hop groups using a sample of the original song. Many things I did in the '60s—I’m not complaining about it, but since we’re talking about it, I might as well tell you—a lot of other people got credit for, which is fine with me. But it’s a fact that I did this stuff so many years ago. What is called world music today—I started the damn thing!

African music is not "world music." It’s a phenomenal music in its own right, but it is indigenous. I worked with Salif Keita on his record called Amen in 1991 and it’s a masterpiece. It was voted in France as best world music record of all time. I produced and I wrote all the arrangements and orchestrations, and composed for it too. The arrangements are very intricate. I’m not trying to put myself in a special spot, but it was so natural for me to play with Salif. Then I found out he grew up with Weather Report’s Black Market. The young African musicians like Youssou N’Dour, Salif and all the West African masters, they all grew up with Weather Report music. In fact, in West Africa they didn’t have the CDs or records, they just had some pirate tapes. So, they only knew my name and thought because it was Zawinul that it was a Zulu band.

Why do you feel you haven’t received proper credit for your contributions to hip-hop and world music?

I think a lot of people recognize it. But, I've been reading a lot of reviews worldwide and many, many writers have credited others in the United States, Europe and Japan as being the first ones to make this music. It's strange the way it goes. But I don't mind the way it goes. I have no problem with recognition—I get plenty of recognition. I have never had a problem. I'm recognized.

Although your work—solo and with Weather Report—possesses a great deal of global influences, most people regard it as fusion, rather than world music.

It's really weird. But people can listen again and judge for themselves. Sony is gonna release a Weather Report album called Live and Unreleased soon which my son Ivan and I mixed. It’s got live and unissued material. This material is absolutely devastating. This is ten times as good as anything we put on record before. The album will be very interesting. It's going to blow people away. It sounds like it was recorded yesterday. I dunno when it’s coming out. Sony is dragging its tail.

A lot of jazz-rock fans point to Weather Report's 8:30 album as one of the best live recordings around.

This is at least on the same level. It’s just really incredible. I think it's better. They also just came out with the Weather Report albums as high-resolution compact discs in Japan. They sound phenomenal. My records sound good too and I give my son a lot of credit for the sound. They conducted a field test in Mix magazine and they chose three records including My People because of the multiple layers and the nice little hidden types of treasures on it. When you hear the disc with headphones, it’s really killer. The next disc is gonna be even better.

You have a live Zawinul Syndicate album titled World Tour due shortly, too. What can you tell me about it?

We've been on a world tour throughout 1997. We've played 106 cities this year—including a few week-long gigs in San Francisco, New York, Tokyo, and Los Angeles. It's quite a tour—we went to Africa, India, South America and Japan and we've been recording these gigs to make a great world tour record. The material draws from My People. Our studio records sound good and they feel like we’re really playing live—which we do. But I’m really looking forward to this record coming out.

How did you first connect with Keita to work on Amen?

I got a fax from Island Records and they requested me to produce his record. I had never heard of him back then and I told him to send me some tapes and they sent me a record and cassette of his traditional Malaysian songs. I listened to the first piece, but didn’t like what I heard, but checked it out further and liked that stuff. So, I took the job to produce, arrange and orchestrate the album. First, Island wanted Quincy Jones and then they decided they wanted to go with me and it was good fun. We recorded in Paris and I improvised all of the arrangements here in the US. I had the lead track of his voice, drum machine, a couple of keyboard lines, SMPTE code, and I had my son Ivan transfer the codes, and I started to improvise the music and that was it.

It got a Grammy nomination in the States. We made the best out of it. We toured—his band and my band together. Last summer, Salif played with my band at several concerts as a special guest.

Stories of the Danube is your first orchestral recording. Why did you choose to make one at this point in your career?

It had nothing to do with me. It is tremendously expensive to make a project like this. It costs a lot of money. There are very few composers that can say they’ve been recorded with a symphony in their lifetime—that’s because of the expense. I was fortunate to meet Karl Gerbel, the man responsible for the record. He was the director of the Brucknerhaus in Linz, Austria. He’s a wonderful guy and had access to wonderful facilities. He gave me the commission to write a symphony several years ago. I was there to play a couple of times with my band and my agent in Vienna spoke with him quite often and suggested it was a good idea to do something with the symphony. He jumped at the idea. When you get a commission, they have to have money—not only for the recording, but just to get the piece written too, because I had to lay off from other things for a few months, although I improvised the whole thing in three days and then I orchestrated it. Everything I’ve ever written is improvised.

There are a couple of pieces in there from a few years ago—like I said, things have to fit. What is called “Gypsy” on the album used to be called “Doctor Honoris Causa” from my 1971 album Zawinul. I wrote it in 1966, and I wrote the last movement suite a long time ago too—it’s also on My People as “Orient Express.” So, I use things because I want to tell a story. It doesn’t matter when I wrote them. It’s all good because it’s not doctored together—it’s a natural thing and it lasts long. That’s why Weather Report has lasted longer than anyone else from its era. Also, improvisation itself is much more lasting. Improvisation doesn’t come from the brain—it’s pre-brain. It’s much quicker and that’s one talent I must admit I do have—I can improvise a long piece and it fits together.

Weather Report, 1977: Joe Zawinul, Jaco Pastorius, Alex Acuña, Manolo Badrena, and Wayne Shorter | Photo: Columbia Records

Weather Report, 1977: Joe Zawinul, Jaco Pastorius, Alex Acuña, Manolo Badrena, and Wayne Shorter | Photo: Columbia Records

Compare your work with Zawinul Syndicate to Weather Report’s output.

I’m still the same person and I’m a better musician now. It’s a different situation, really. I didn’t have a guitar player with Weather Report and now we do. I had a sax then and now we don’t. There is an interpretive difference perhaps, but the music is still mine and a lot of the things you hear me do today, I wrote then. I wrote a lot of the music I play today back then. I’m making new music almost every day when I’m not on the road. Over the years, I have written perhaps 5,000 pieces of music of different lengths. I like having a concept for records so the pieces fit together. That’s what I did on My People too—I needed something little to finish the album with and found this piece called “Many Churches.” I don’t know when I wrote it. I wanted to record it with a choir first, but I didn’t have the finances and time, so I did it as an instrumental. For me, a record is a statement—a storytelling experience—and it’s gotta fit together somewhat. I like there to be a line through the whole album and in that way, My People is very successful.

Critics, music historians and fans alike point to Weather Report as a band that truly changed the face of music. What’s your assessment?

We started playing using electronic instruments in a way they had never been used. It’s just fine music played with different instruments. Also, the compositional quality of Wayne Shorter and myself, frankly speaking, is unique. The way we put together quartets and quintets—there was nothing missing. Weather Report sounds as fresh today as it did then. We always had great musicians and I still do. I’ve always had great musicians. They’re the only ones who can even approach this music. I’d never have a guy play bebop in my band—it would not fit. I don’t play bebop, I play another type of music. Dizzy Gillespie once called me to say “Man, I just heard one of your records. That’s music, man.” That really made me feel good because we had some funny backlash from people who said we were selling out because we were using electronic instruments. It’s such idiocy. It’s ridiculous that someone could place that much importance on the instrument to be that great. An instrument is not important. It is the way one plays that is important. Instruments don’t play by themselves. A piano is certainly not a better instrument than a synthesizer, but if a synthesizer is played like a piano, it becomes a very bad instrument. It doesn’t work. You can’t play a trumpet like a violin—it doesn’t go. That’s the problem—the players, not the instrument. Any instrument is a wonderful thing.

Describe the circumstances that led to Weather Report disbanding in 1986.

Our contract ran out—that was number one. Also, the name Weather Report suffocated me and Wayne. Weather Report was more well-known than we were. Weather Report toured and did a record every year and there was no time for me to do anything else. I had offers to play classical music and other things and they are experiences one has to have. When I grew up, I had very little time to play classical pieces and I had the opportunity to do so with a friend of mine from Vienna named Friedrich Gulda. He’s the greatest Mozart interpreter of the century and he invited me to play with him at his concerts. It was a very good thing to try out, but I’m not a Mozart player. I don’t really like Mozart. To me, it doesn’t mean anything. But I do like Brahms and we decided we’d play the “Haydn Variations” for two pianos—the best piece ever written for a piano duo. It’s very difficult to play and it was a challenge for me and that’s what I did right after Weather Report.

If you asked Wayne, he’d tell you the load of the work was on my shoulders. During the band, he worked with Milton Nascimento and Joni Mitchell—he had that freedom more than I did. I didn’t really have time to do the little projects I wanted to. It got tiresome, although the band was always a wonderful band. It was a great partnership for 16 years and Wayne did work too, but the main load was dropped in my lap and I wanted to get away from this and he also wanted to get away. There was a great opportunity to do so. You play 16 years together and what do you want in life, you know? [laughs] With a great musician like Wayne, it was fantastic and we’re still great friends today, but it was time. I’m very happy that we did it.

Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul, 1986 | Photo: Columbia Records

Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul, 1986 | Photo: Columbia Records

In 1996, you and Shorter negotiated with Verve to reform Weather Report. Why didn’t it work out?

We did talk about it, but it didn't materialize. It was the idea of the late Anna Maria Shorter. But we had our price and when the price was not met by Verve, we abandoned the idea.

My assumption is there would have been a great financial incentive for the label to make a reunion happen.

Yeah, but maybe it had something to do with the fact that Wayne's last record didn't sell as well as they hoped it would. And the money was big.

The years immediately following Weather Report were challenging for you. First you went out on the road with Weather Update—a band featuring several Weather Report alumni. Then you went on a solo tour. Neither were consistently well-received by critics and audiences. How do you look back at that period?

We had to take care of business. That’s why we did Weather Update. And immediately after that I made a nice solo record called Dialects which is the best record I’ve ever made in my life. But solo touring in the beginning wasn’t a big success because people didn’t believe I was really playing everything they were hearing. Some reviews of the concerts said "Zawinul is cheating. All he is doing is mixing the sound." And in reality, I was doing everything. I didn’t even use sequencers. I played all the music live—I had two drum machines because I needed those rhythms, but that was it.

Joe Zawinul, 1984 | Photo: Columbia Records

Joe Zawinul, 1984 | Photo: Columbia Records

I understand you believe America is in cultural decline because there are far fewer storytellers than there used to be.

Everything is in decline the moment you stop giving the artist freedom. That goes for everywhere, but it is happening in America right now. I think record companies are at great fault. In general, they don’t want to develop talent, but rather get the most out of them in the short term. They’re steering people to do things they perhaps wouldn’t do but have to do and not everyone has the integrity to say “No way.” People are hungry and they have to make money and take care of their families, so it’s a great pressure. Only when you can afford it from an artistic or financial point of view can you express what you want to express. Before I made My People for an independent label, I was with Sony for a long time and then there was interest from Verve Records over at Polygram. They told me at the first meeting I had with them—and it was the only meeting I had with them—that they wanted me to sign up but only to play acoustic piano on the first record and only Duke Ellington’s music. I got up and left.

Despite you being a big Ellington fan?

I’m the Duke Ellington fan, but that had nothing to do with it. They were telling me what to do and not only that, it was a question of “What is in it for me to play Duke Ellington’s music?” I’m a composer. I like my music and I like it as much as I like Duke Ellington’s music. Duke is one of the greatest musicians who ever lived, but everybody is an individual and it has nothing to do with being better or not as good. It’s about the storyline—what you have to tell. And in that respect, I like my music just as much. It sounds very different, but in principle it’s still the same.

So where have the individuals—the storytellers—gone?

They are many storytellers, but they’re hidden somewhere. In the old days, that’s all you had. You didn’t have these phenomenal music schools which are everywhere today. That was not so good because the people didn’t play their instruments as well as they do today. That was the way times were. If you didn’t have a sound of your own, you couldn’t make it. All the guys I used to play with when I came to America—each one was a different individual. They had different sounds and different ways of playing and that’s what made the business go around. But today, jazz has become very boring. And when I talk about jazz music, I’m talking about who everyone talks about when they talk about jazz.

Wynton Marsalis is often invoked as epitomizing jazz for the mainstream these days.

To me, this is very boring music—most of it. It has nothing happening. Nothing is sticking. They’re playing music perfectly with wonderful intonation and technique, but it’s dangerous for jazz itself. I do wish these people all the best. I’m happy that it goes like that in a way because we used to live like rats when I didn’t make any money. We used to have to play every night and drive everywhere. We didn’t have the accommodations available today. It was a difficult time, believe me. We all had families to support. I very much respect Wynton as a noble guy who is doing a lot for keeping the great names alive, but the music comes up short. Those little upstarts—that age group, it’s not happening. When I listen to old Cannonball, Horace Silver, Blue Mitchell, Art Blakey, and Miles stuff, it’s way, way, way superior. It’s in another league—the fire, the excitement. But that doesn’t mean the new guys don’t have it, they’ve just been geared to do the same stuff. I was able to afford to say no, but how many people can say no to a major league contract? Wynton has enough power to do what he wants to do, but it’s just not my cup of tea.

I just don’t like stuff that’s warmed up. It’s not bebop what these new guys are playing. Jazz music is a lifestyle. It’s not notes, chords and arpeggios. Today’s improvisation is too based on the knowledge of chords and the way they practice the chords. It’s not a melodic thing anymore like the older days. It was much more important to play shorter and to play more variable, valid stuff. Today, a lot of solos are long and uninteresting and the influence usually comes from John Coltrane’s group. He himself was a master musician, but he put so much emphasis on chord knowledge and technique, and now the kids want to show how fast they can play. This is the same with piano players and most instrumentalists—it’s speed. That’s gonna change again and hopefully the kids who are now 16 and 17 years old have a little more sense and maybe some more stories to tell. The other kids from the other generation came right out of school and immediately got a record contract. Do you know how difficult it used to be to get a record contract in the olden days? It was almost impossible. And then if you did, the record distribution was so tiny and small. It was very difficult.

If I was coming up now, I don’t think I’d enjoy going in their direction musically. But it’s not their fault and it’s not criticism because it’s not just music. Everything happens like that. It’s a spiral going down. In the arts, music and movies, everything is now geared to a specific audience—the young people, who in general listen to music. And it’s not music anymore. Rock and roll was a great movement and very important to all of our lives. It made it possible for jazz musicians to get a piece of the rock. It was a great change and cultural movement, but the way it has developed has become more and more ugly. The way songs are being performed today compared to the old days—now, you don’t understand the words and they have so many embellishments and very little substance. I hope I don’t sound like I have sour grapes. I’m a very happy person. But if you ask me, I’ll tell you what I think and it’s just not happening for me.

Joe Zawinul, 1956 | Photo: Philips Records

Joe Zawinul, 1956 | Photo: Philips Records

Describe your transition from straight-ahead jazz to the much more expansive approach you brought to the form in the ’60s.

I was tired of the standard form of jazz—you know, the A-A-B-B and the changes. I was fed up with that. Sax, trumpet, bass solo, then drums, and back to the melody—that bored the shit out of me after years of doing it. That’s when I started changing my music and totally opened it up with a lot of great musicians. Thelonious Monk and Dizzy Gillespie came to my house one Saturday morning and Monk heard one of my tunes and said “Man, what are you doing? I really like that! You’re the only one doing different things.” And like I mentioned earlier, one time, Dizzy called me on Thanksgiving in Oklahoma and said “Man, this is the way music should be”—this was a few years before he died. I knew I was on the right track and Wayne Shorter and me, we understood each other since we first met in 1959. I met him not long after I arrived in the States and we decided one day that we were gonna work together and have a band. Wayne comes from a different direction, but he already had that kind of openness with no limits.

Many point to the work you did with Miles Davis in the late ’60s as the music that most significantly impacted your musical evolution.

It is the other way around, frankly speaking. I think he got more from me than I got from him in that respect. The only difference is that I was much younger when I first heard him. I was very young in 1948 when I heard Birth of the Cool. It influenced my music, but it didn’t influence my life. I knew Miles until he died in 1991. Bitches Brew wasn’t the end of Miles and me. We spent a lot of time together talking about music following Bitches Brew. I did five albums with him and he was a great, wonderful guy and philosopher. We didn’t pay that much attention to music itself. Music is the result of things. It’s not the thing itself.

I understand you don’t look back at Bitches Brew as the landmark album many believe it to be.

No, I don’t. But I’m not a critic and what I like, I like, and what I don’t like, I don’t like. It’s a good album with a nice atmosphere. I don’t think there’s anything earth-shaking about that record. When we got out of a session, Miles drove me home and he asked me why I didn’t say anything during the ride and I said “I didn’t like what we did and what is being done.” It’s a good-sounding record. There’s a lot of power on those sessions. Everyone had respect for each other and no-one overplayed. It could have been utter chaos, but it was pretty organized.

How do you look back at your tenure with Cannonball Adderley?

The impact he had on my life is great. I played almost 10 years with Cannonball. He’s the most underrated musician of the 20th Century. Hardly anybody talks about Cannonball, but he was a giant. He was his own guy. He didn’t play like Charlie Parker. He played like no-one else. We had one of the longest-working, most excellent bands in the history of jazz. It’s all a part of me today, but not to the point where I’m obsessed by it. But there are no bands today. The record companies are always trying to put together names and it’s usually bullshit. They want everybody to be a star and it never sounds like a band—it sounds like some guys put together to make a good buck.

You've curated a forthcoming album called of recordings from your period with Adderley titled Cannonball Plays Zawinul.

Yeah, that makes me feel good. I did a lot of writing for Cannonball’s band. I had a large amount of songs on several albums, but this is a nice thing because I always liked Cannonball and his band.

Do you hold Jaco Pastorius in the same esteem as you hold Davis or Adderley?

No. I think Jaco was an inventor. He created a style and had a wonderful soul as a human being. But he didn’t live long enough and he didn’t contribute enough to be in the same league. Longevity is something. He was a phenomenal talent in music and other things too. He could paint and draw. He was an architect and a national athlete. He was a wonderful friend and he felt like a brother or son at times. But in terms of creativity, I cannot put him on the same level as Miles or Cannonball. I think he was just as influential as they were—maybe even more than Cannonball. People are sleeping on Cannonball—people still don’t get him. Cannonball was awesome—an incredible musician. He never stopped and never played the same thing twice. I never heard him make a mistake—he was a master. But with Jaco, I think there was a limitation there.

What was it?

Maybe he didn’t allow himself to get there. He was once in a house in Germany with a Gypsy friend of mine and he wrote down my name with my birthday and his name and his birthday and then the other page says “I don’t wanna be a second-hand Joe Zawinul.” He was somehow occupied with me too much. We were also true friends and I think that friendship lasted to the last day. Jaco always loved as a friend, a man and a musician and hoped he could have done better than he did. After Weather Report, he made a nice record with his big band. But he had deteriorated—he didn’t have any hold or anything, because he really wanted to be with Weather Report. We didn’t fire him or anything and he didn’t leave. What happened is, in 1980 we had all these contracts and he wanted to take off for a year and Wayne and me said “Jesus Christ, we have to go on. We can’t wait a whole year until Mr. Pastorius comes back.” And he might have thought at the time that he was not replaceable, but there is nobody in the world who is not.

John McLaughlin, Joe Zawinul and Jaco Pastorius, Havana Jam, 1979 | Photo: Columbia Records

John McLaughlin, Joe Zawinul and Jaco Pastorius, Havana Jam, 1979 | Photo: Columbia Records

Many credit you for bringing Pastorius into the public spotlight, but others have intimated that you weren’t always the best role model for him as far as recreational substances went.

I never introduced anyone to drugs. I’ve never used drugs. I gave Jaco a drink one time. If one drink does it, you’re a goner anyhow—believe me. I gave him a drink one time and told him to loosen up—I did do that. If one drink did it, then I’m responsible for his downfall. But drugs? I never used drugs myself.

You were quoted in GQ magazine as saying "By 1980, Jaco was always angry and drunk. He began to try to out-macho me, to out-drink me, as if it were a competition or something. Sure, I drank and occasionally did a little blow, but I liked myself too much to hurt myself."

Hardly, hardly. [pauses] I smoked a little pot here and there and had a little thing [makes a sniffing sound] once a month or something, but it was not a thing to do. I was a busy guy, man. I had a lot of work to do. I was into music. We were in the studio 46 hours sometimes to mix a record. I'm not stupid. I had a family with three children to feed. I was a real connoisseur about that. I haven't done drugs in 25 years, but here and there when the stuff was right and we were very tired, yeah, I had a little blow. But it had nothing to do with being strung-out or needing the stuff everyday. Wayne and me were drinkers. I'm still a drinker, but I'm 65 years old and I don't look like I'm a wreck. Usually, when people drink they look like wrecks by the time they're in their 40s.

You're known as extraordinarily demanding bandleader. Tell me about your perspective on driving musicians to do their best work.

I am. Because when I play alone, things are so clear and I want clarity in expression. I want to tell a story and when you tell a story and then you have to tell it with other people, it's very important that there is great discipline. I don't mean playing arrangements, I mean songs. I make up the arrangements and cues. It's like a conductor playing with an orchestra, but a conductor has a score in front of him and the musicians have music. On Stories of the Danube, there are improvised parts, but the bulk of the music is written and will never change, so it has to be conducted correctly. The record is not nearly as good as the same orchestra plays it now because we've performed it several times since recording it. What happened when we went to the Czech Republic to record it with the philharmonic orchestra is that they had not seen the music. My music is much more difficult than Beethoven’s music or Mahler’s music because the rhythmic structure of my music is coming from the ground. And it’s not like Mozart’s music in which you always have the rhythm provided with the violins and woodwinds moving in a 16th-note pattern. My music doesn’t do that. One section of violins might break up into up-beats and others might come in on top of that.

Portishead used Weather Report samples from "Elegant People" on the track "Strangers" from its album Dummy. The band received permission prior to doing it and gave you full credit. What did you make of the outcome?

It's not strange at all. It's really, really nice. I think some of the sampled music has some artistic value. I have no problem with someone doing something new.

You’ve said you're selling a lot more records in Europe than America. Why do you believe that’s so?

Yeah, it’s true. I sell a lot of records in Europe and Japan. In America, people don't work the way they work over there. Also, the audience is much more alert there. We're successful in America too. We sold out every night at Yoshi's in Oakland, Catalina's in Los Angeles and The Blue Note in New York. But selling records is different—especially without radio support. I'm also with an independent record label now. But if you're with Warner or Verve, they have so much money. They can put a lot of money into an artist. I'm with an independent company and I like them. I can do what I want to do. They treat me well and I'm doing very well, financially. But in America, unless you have advertising all of the time, it's very difficult. I've dealt with that record industry stuff for so long. I don't expect anything. I really, really don't.

Your son Ivan is playing a significant role in your career today.

Yeah, Ivan is 28. He's my engineer, my keyboard guy and we always work together. He's phenomenal. He has an incredible knowledge and it's the way I like it. He has great ideas too. He put together the drum rhythm on "Potato Blues" on My People. It’s a pleasure to work with the family. I didn’t have to encourage him to pursue a career in music. I haven’t had to encourage anyone in my family to do anything—they just do it. They know what it takes to make a living and they work hard.

What are your thoughts about your own mortality?

I’m not afraid of death. The reason could be that I grew up in an environment in which I was always exposed to death every day for years. Experiencing bomb attacks in the night and day and actual war in your country is very different than watching a war a thousand miles away from your home. We had the war right there in my house. The Russians came in and many of my friends died, so this type of life prepares you for death. When I was a kid, I used to bury people—dead soldiers and all that. At age 12, I used to steal horses from the Russian wagons and kill them for food. I ploughed fields with oxen. That was my life. The kids were the men. I was trained for the military—I was a bazooka man. But going back to mortality, I felt when the war was over, everything was easy, but I went through some very hard times in America too. I was the only white guy to play with black bands in the South during segregation. I often had to sit in the bottom of the car when we drove through certain parts of the South. Those kinds of things never fazed me. I wanted to play music with the best and I could play on that level with the best.

You’re an avid boxing fan. Are there any similarities between the lives of boxers and musicians?

I box when I'm at home every week with my trainer and I do sports every day. Boxing is the greatest sport in the world and really, it’s not even a sport—it’s a passion. It’s funny, I know a lot of boxers and they all love music, and all the musicians I know really love boxing. There are parallels in terms of improvising music like I do. And you can’t blink an eye. You’ve always got to be alert or you’ll miss the moment. It’s all related. You gotta use your limbs, hands and feet in music and you have to do that in boxing as well. But when you make a mistake in boxing, you’re gonna have a problem. [laughs] If you make a mistake in music, you’ll have less of a problem. You’re not gonna get knocked out!

Listen to the audio podcast version of the interview: