Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Bob Nyswonger

Perpetual Motion

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2025 Anil Prasad.

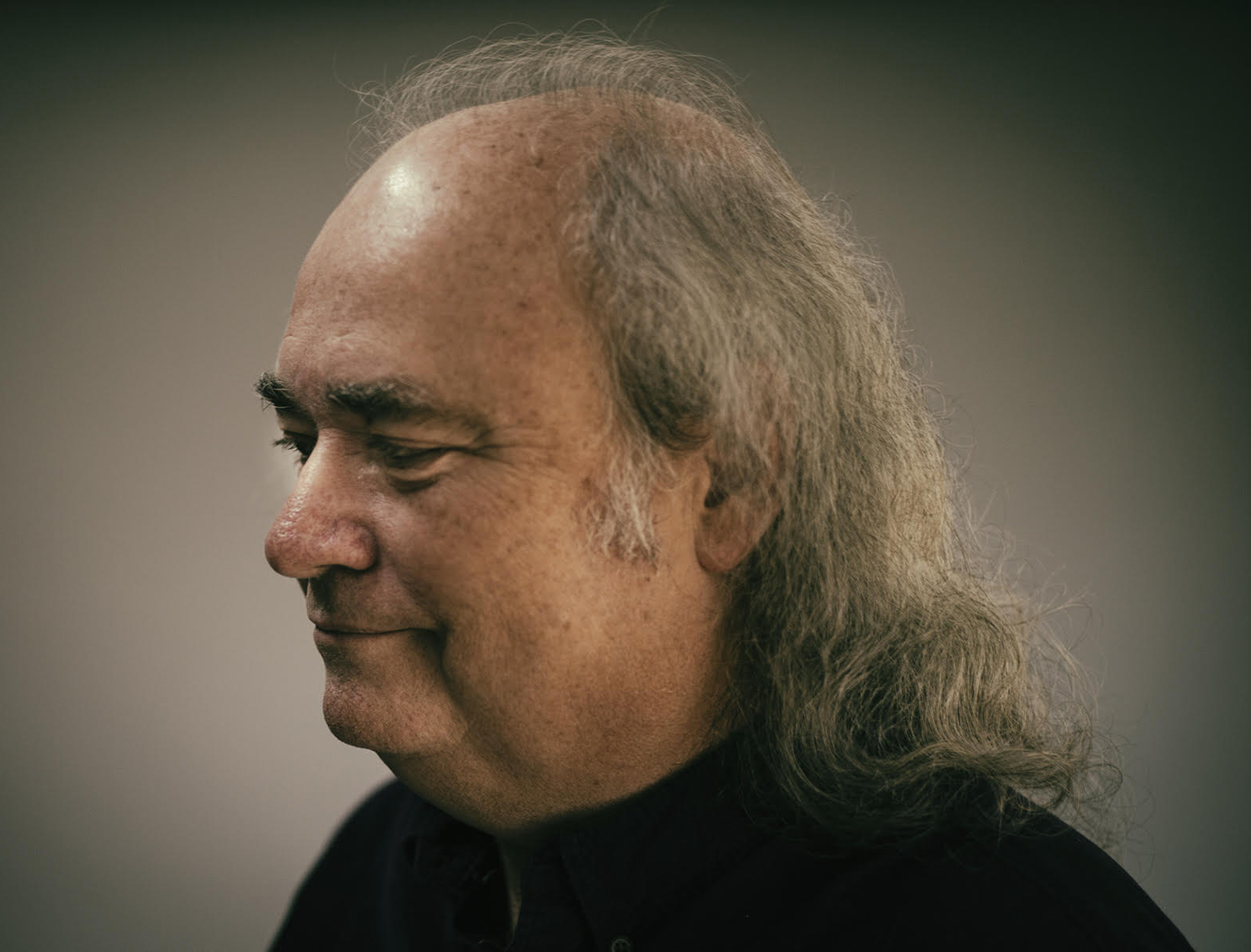

Bob Nyswonger in his Cincinnati home music parlor | Photo: Anil PrasadCommunity is at the heart of bassist and singer-songwriter Bob Nyswonger’s career. Since 1977, he’s been a critical mainstay of the Cincinnati music scene, playing in some of the region’s most important bands, including The Raisins, Psychodots, Graveblankets, Tickled Pink, Bucket, The Bluebirds, and New Sincerity Works. During the 1980s and 2000s, he was also a member of The Bears, the globally-renowned act that had its roots in the area.

Bob Nyswonger in his Cincinnati home music parlor | Photo: Anil PrasadCommunity is at the heart of bassist and singer-songwriter Bob Nyswonger’s career. Since 1977, he’s been a critical mainstay of the Cincinnati music scene, playing in some of the region’s most important bands, including The Raisins, Psychodots, Graveblankets, Tickled Pink, Bucket, The Bluebirds, and New Sincerity Works. During the 1980s and 2000s, he was also a member of The Bears, the globally-renowned act that had its roots in the area.

All of the bands have a foot in the rock universe, but also extend their output into art-pop, folk, folk-rock, and Americana realms. Many of them share members. Perhaps the single most important thread that runs through them is the fact that they're all friends and support one another.

As a bassist, Nyswonger is a master of groove, dynamics, and propulsive drive. He also delivers blazing, deep-in-the-pocket solos when the inspiration strikes. As a songwriter, his lyrics are often observational and philosophical, and explore the nuances and proclivities of human interaction. He’s also unafraid to delve into the impacts that result from our less enlightened tendencies.

Nyswonger can be found on any given evening performing with combinations of musicians from Cincinnati’s elite musician circles, including singer-songwriters and multi-instrumentalists Scott Covrett, Roger Klug, Lee Rolfes, Marcos Sastre, and Greg Tudor.

All of those people, not to mention fans that attend the gigs, are fans of The Raisins. The seminal band existed between 1975-1985 and essentially created the indie template most of the region’s acts built on.

The question of whether or not The Raisins would reform again lingered eternally among Cincinnati music aficionados of a certain vintage. Apart from three shows in 2000 and one in 2011, the band remained quiet for most of the 40 years since its breakup.

In 2024, fans got a definitive answer when The Raisins made a surprise return to active duty. Nyswonger reunited with the group’s classic lineup of guitarist Rob Fetters, keyboardist Ricky Nye, and drummer Bam Powell for a series of six gigs in Cincinnati. The concerts found The Raisins in superb form as they expertly reprised their classic repertoire. The gigs proved such a success that the band chose to continue, with further shows ahead in 2025 and potentially beyond.

The Raisins are also the subject of a recent in-depth documentary titled The Bends, written and directed by multimedia artist Mike Tittel. The limited-run film digs deep into the group’s storied history, using the 2024 reunion performances to frame its mercurial journey. Notably, Tittel is also a respected singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, and the leader of New Sincerity Works.

Innerviews met Nyswonger at his home in Cincinnati, where he discussed the majority of his musical endeavors past, present, and future. It’s a warm, welcoming environment surrounded by instruments, and features multiple music rooms. His basement is a recording studio where he’s documented and rehearsed with his many bands. The dwelling also includes a colorful parlor with a baby grand piano and upright bass, and a living room infused with Bears, Raisins, and Psychodots memorabilia, not to mention a serious old school stereo setup. During most nights, Nyswonger and his friends are found there listening to LPs, CDs, and cassettes from across every genre imaginable.

During the interview, Nyswonger was clad in a blue shirt, jeans, and sneakers, and was relaxed, upbeat, and thoughtful. He’s still got a touch of rock shag in his gray hair, and at age 69, possesses youthful enthusiasm about life and the world of music.

What's your view on the value of music in this era of ultra-polarization and societal chaos?

That’s a big question. I think because music is so widely spread through our culture and so easily accessible that it has lost some of its value—certainly its monetary value. But I think the thing inside people that makes them appreciate music is always going to be there. It will never change.

Culturally, musicians have been appropriated by the tech industry, so it’s much harder for anybody to try and earn a living. I saw it coming a quarter century ago, which is when I got a real estate license. That’s when Napster emerged. I could see the writing on the wall. The idea from that point on was “music is free.” And while that’s great for listeners, we used to have mechanisms for compensating artists and songwriters. Now, unless you reach certain levels of media, you’re not going to be compensated.

Music is a spiritual thing for me. It’s almost like a substitute for going to church. Music does still have a profound personal effect on everyone, and brings people together regardless of their beliefs. Personally, I still love to experience the connection I have with artists I admire through their music. And thankfully, people still come and see me perform as well.

If I’m really in the zone when I perform up to what I consider my standards, I know it’s as good as it’s going to get for me. That’s my highest moment of spirituality.

Bucket: Lee Rolfes, Bam Powell, and Bob Nyswonger | Photo: Grace Powell

Bucket: Lee Rolfes, Bam Powell, and Bob Nyswonger | Photo: Grace Powell

Explore the formation and journey of Bucket.

Lee Rolfes is 15 years younger than me, so we didn’t travel in the same circles. But back in the ‘90s, he was in a rootsy, folky duo playing guitar and singing with Mark Gillespie. People told me they were performing The Bears’ song “Trust,” which I wrote. I thought it was really cool they were doing that. It was around the time Psychodots were winding down in 1997. Rob Fetters wanted to dial it back because he was involved in a lot of studio and production work.

So, I was looking for ways to keep my chops up and keep playing. A bass player has to play, or you lose your calluses and there’s nothing worse than that and having to go through the pain of getting them back. It’s the only way I can physically remain able to play. It’s a perpetual motion machine.

Lee and I connected. Around the same time, Bam Powell was working with The Bluebirds. We remained friends over the years. Bam was doing this thing at the time in which he’d create a drum kit with buckets, saw blades, and tin cans. The kick drum would be a pickle bucket or recycling bin. He’d figure out a way to hook a pedal up to it and he’d just start banging on stuff. It was fun. That’s where the band name came from. Lee would play acoustic guitar with him, and I said, “I’ll come and play upright, and we’ll learn some stuff.”

When we first started, we didn’t have that much original band material. We were doing songs Lee had written, as well as Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan tunes. Of course, we did “Trust,” because it was already in the repertoire. It was all quality stuff. Lee liked it well enough that he used Bam and I on his 1998 record Further Down the Line. And we kept doing it and Bucket turned into a thing of its own.

Everyone started bringing in their own songs. The format of the band, with me playing a big old doghouse bass, meant the songs had to be kind of elemental, and not require major chops. It’s basic music, which had some appeal to me. I was also playing upright in The Graveblankets during that period. I prefer the electric bass though, because it’s easier to carry around.

Reflect on the making of the Bucket’s third album Wall-O-Matic from 2023.

It’s a fun record. We recorded that one in my home studio in the basement. It’s always a little nerve-wracking for me, because I have to be the engineer and the bass player at the same time. I have to make sure the gear is going to work. We managed to get it together, Lee re-tracked some of his guitar at his home studio. But that’s the nice thing about modern technology. Everybody’s got a way to record at home. If you’re unhappy with something, you can easily fix it and not be a slave to the studio. But there are some things I miss about great recording studios, too. So, it’s a compromise.

I wrote a song called “What’s Wrong With Me?” for the record. We also did my tune “Copy Machine” that I wrote for Psychodots. Bam and Lee brought in most of the material for the record. But we all had input into the arrangements. It all goes into the Bucket filter. So, the songs didn’t necessarily sound like the demos. Everything evolved.

The great thing about working with your friends is everyone has a lot of regard for each other. So, it’s a very positive situation. And I only work with people I like. I need to have some kind of bond, friendship, or mutual respect with people I make music with. Otherwise, why do it?

Tickled Pink: Scott Covrett, Bob Nyswonger, and Bam Powell | Photo: James Campbell

Tickled Pink: Scott Covrett, Bob Nyswonger, and Bam Powell | Photo: James Campbell

Let’s dig into Tickled Pink, which also has three records to its credit. Talk about establishing the group and its focus.

Lee Rolfes moved to Nashville at the turn of the century, so I was in the vacuum of not being able to play enough to keep my hands in shape. Bam had been playing in a three-piece called Curly with a different bass player. For one reason or another, they said, “Let’s get Bob to play bass.” So, I was invited to be a part of it. I’ve known Bam forever and knew Scott Covrett as a fellow former Sylvania High School guy. He’s a great guitar player and was also in The Raisins briefly in 1975.

Like Bucket, we started by focusing on cover material, with everyone bringing in songs they like. We did material by Los Lobos and The Rolling Stones. We eventually started making records, and we’ve made them all here in my home studio, too. They’re all self-produced.

We took our time making those records. We might record three or four songs a year, and then eventually, we’d get to the point where there were enough songs for a record. It’s a cool band. I love bringing in songs and seeing what Scott and Bam do to them. They always bring so much to them.

The first song on the first Tickled Pink record is “Moment of Truth” which I always thought would have been a great Bears song. That’s who I had it in mind for. But it was great to have Scott sing and play on it.

Tickled Pink only plays locally in the Cincinnati area. So, we’re not forced to tour all the time in a van. We all do other things. So in this case, familiarity doesn’t breed contempt.

New Sincerity Works: Roger Klug, Greg Tudor, Bob Nyswonger, Mike Landis, Lauren Bray, and Mike Tittel | Photo: Michael Wilson

New Sincerity Works: Roger Klug, Greg Tudor, Bob Nyswonger, Mike Landis, Lauren Bray, and Mike Tittel | Photo: Michael Wilson

Since 2014, you’ve also been part of New Sincerity Works led by Mike Tittel. Discuss your contributions to it.

I knew Mike Tittel from his work in the group Pidgin. In 1997, the late Shawn Marsh, who was the soundman for Psychodots, said Pidgin wanted to use me on their debut record. I came in totally cold. I didn’t know them. They just knew me by reputation. They were younger than me and were Raisins and Bears fans. Pidgin did very challenging music.

I didn’t see Mike for a while after that, until I saw him play with The Roger Klug Trio. My wife Laura had gone to see them a couple of times without me, because I was playing with The Bluebirds at the same time. She said, “You’ve got to see these guys. You’re going to love them.” So, I went, and I did. We started hanging out and became friends. I even helped Mike buy his house.

At one point, Mike was going through a tough personal situation, and he was writing songs related to it. It was like therapy for him. I said, “Well, if I can help, I’d like to play on them.” So, I recorded a couple of tracks for what went on to become the first New Sincerity Works record titled 44 that was released in 2014. It was also cool, because it was my first opportunity to work with Roger during a recording.

I really like Mike’s songs and his singing. My favorite New Sincerity Works release is Wonder Lust from 2017. It was also so cool to see that album come out on vinyl. It was the first vinyl album I’d been on in 30 years—since The Bears’ Rise and Shine. They also mixed the bass up hot.

Mike also had me play on his solo album Sleeping In from 2020. That’s a really good record as well. We then went on to work together on the last New Sincerity Works album, Heirloom Qualities from 2021. I’m on several tracks on that one. It also came out really well.

New Sincerity Works is mostly a recording project. It has played live just a few times over three years. There’s usually a showcase gig for when a record comes out.

Most of your bands have multiple lead vocalists. Explore your attraction to that format.

I think it’s because most of the musicians I play with sing and have common influences like The Beatles, Todd Rundgren, NRBQ, and so many others. I think all of us felt “It would be so cool to pull something like that off ourselves.” Rundgren’s Something/Anything? was an eye-opener. As a result, everybody tried to learn how to do things well enough on their own, too. I played most of the instruments on my solo record Deposition, with the exception of Chris Arduser, Adrian Belew, and Bam Powell playing drums, and Rob Fetters playing guitar on one track.

I have too much respect for drummers to attempt to play drums myself. I’m very fortunate to have worked with some really great drummers like Bam, Chris, Mike Tittel, and Mike Hodges. Most of these guys are multi-instrumentalists and have made records entirely on their own. And because everyone makes their own records, when we’re in bands together, we’re all able to put the egos aside and go, “The best song wins.” And usually, the person who brings the song in sings it.

This approach goes back to The Bears. When we’d bring songs into that band, it was a bit terrifying. Sometimes people you love and respect say, “I don’t know…” But I’ve been lucky in that The Bears were willing to do a lot of my stuff.

Psychodots, 2016: Rob Fetters, Chris Arduser, and Bob Nyswonger | Photo: Michael Wilson

Psychodots, 2016: Rob Fetters, Chris Arduser, and Bob Nyswonger | Photo: Michael Wilson

How do you look back at your time with Psychodots?

It was always fun for me. I really brought my A-game to that band, recording-wise and performance-wise. There was a little bit of frustration in that I wasn’t ever able to sing in it. Rob Fetters and Chris Arduser wanted to sing and didn’t want me to. That’s just how it evolved.

When The Bears were playing in the 1980s, Chris barely sang. And then when we came back and did Car Caught Fire in 2001, Chris was a lot more involved as a singer because he had proven himself on all the great Psychodots and Graveblankets stuff. Everybody knew he could really sing. But you don’t need four singers in a band. A couple of times, I sang “Caveman” when Adrian Belew wasn’t feeling well. I wrote that one, so I could handle it.

My favorite Psychodots record is On the Grid. It was the second album, and we all had a lot of input into it. We also had some management backing, so we had two whole weeks in the studio to do it. It was a really concentrated effort and came out really well. By the time we got to Awkwardsville, I was a little frustrated, because there were some songs I brought to the band that I felt should have been on it, but weren’t. At that point, Rob was getting more into the production side of things and finding his stride. It’s a great-sounding record, but I remember being slightly frustrated as it went down.

I got my footing back a little when we did Terminal Blvd., and I was happy with my contributions and the way they came out. But there are some songs we played live that never got the full production and recording treatment they deserved. Some are on Psychodots’ Official Bootleg and others are now emerging with Tickled Pink and Bucket.

I think as a band, we were always kind of unmanageable. We were still working with Stan Hertzman a little bit, who also managed The Raisins, but we wanted to be independent. We never hired publicists. We put out the records, and frequently local radio would show us some love. But the hope always was for somebody who could advance our career to get behind us, but that never really happened.

We had a measure of success with The Bears in the 1980s. So, I think we felt we understood what it took to do good work that has some legs and commercial viability. But for whatever reason, Psychodots didn’t get that level of attention. I don’t know why popular music becomes popular. We had a lot of pop sensibilities and wrote tight songs. We’d like to have heard them on the radio in another town.

Photo: James Campbell

Photo: James Campbell

Psychodots emerged out of The Bears breaking up. But it initially used the name The Raisins for the band. Talk about that transition.

After The Bears, Adrian Belew went on to do the Mr. Music Head record, and the Sound + Vision tour with David Bowie. It was obvious he was going to focus on his solo career, which is only natural. But Rob Fetters, Chris Arduser, and I felt we had a really solid foundation, even as a three-piece. So, we kept playing. We did some Bears stuff and new material. It wasn’t the same band, but it was a solid entity. And then we decided to start putting records out.

We started as The Raisins, because that was the name people knew us as in Cincinnati. It was a matter of getting booked. People would say, “Oh, The Raisins? They’re back.” But eventually that didn’t feel right, because it didn't have Bam Powell or Ricky Nye in it. So, one night, we were playing at a club, and we asked the audience, “What should we call this band? We don’t want to be The Raisins anymore.” And somebody yelled out “Psychodots!” We said, “That sounds good.”

So, that was it. We wanted a new identity and chose that for it.

What was it like to perform at the 2018 Psychodots farewell gig at the Woodward Theater in Cincinnati?

That was a tough gig because Chris Arduser was having a lot of personal trouble. It almost didn’t happen. We had done a few shows earlier that year and saw a change in him and his performance abilities that was undeniable. It was disturbing in that we were used to having everything at a very high level. So, we almost pulled the plug on the final show, but Chris said he really wanted to do it.

I could tell the desire was there for Chris, but we were hanging on by our fingernails during the show to get through it. And it was a pretty good performance. We put out a DVD of it, so there’s a nice document of it.

Chris was such an incredible musician and good friend. It was a painful thing to go through, in terms of the changes and his passing in 2023.

Elaborate on what made Arduser such a special presence.

He was so gifted. He was an incredible drummer—and he was even when he was age 13. And he taught himself how to play so many stringed instruments. He became a fine guitarist and mandolin player. He was also a really good vocal arranger. There wasn’t a whole lot Chris couldn’t do.

Chris invested his own money in producing his own records, but he wasn’t able to get quality bookings for The Graveblankets. So, we didn’t play live too often.

I remember one period in the mid-‘90s when The Graveblankets had a weekly gig, and the band got really good. It was the lineup with George Cunningham on guitar, Karen Addie on violin, and Chris and Bridget Otto singing. But things kind of fizzled out with the band, eventually. I wasn’t a party to the inner workings of it. I was just a guy in the band.

Chris released many records as a solo artist and with The Graveblankets. It’s all very high-quality stuff and I play on most of them. But it was always a shoestring operation. It was a case of, “I can get this studio for two days, so let’s go in and see if we can cut four tracks.” So, they were recorded all over the place with different engineers. The common thread is Chris produced it all. He left a lot of great music behind for the world to appreciate.

What are your thoughts on the two-part existence of The Bears?

The first part of the band’s run was kind of a whirlwind. I’m so grateful I got to do it. It was a chance to make records and play with Adrian Belew all over North America, Canada, and Israel. Those experiences will always be a part of me and helped make me who I am.

The Bears was a fortuitous experience for all of us, including Adrian. I think it was great for him to be in a band again in which he didn’t feel like he had to direct everything. We all had faith in each other and a collective vision for what the band should be and sound like. So, those were great days, and I wouldn’t trade them for anything.

When we got together the second time, we were a lot more experienced and mature as musicians but still writing really cool tunes. We were able to bring another decade’s worth of experience into the band and I think Car Caught Fire and Eureka! are the best records we made.

Unfortunately, during the second run, we didn’t have the same level of support as the first time. Everything we did was on our own at that point. We had a booking agent, but that was about it. We never made enough money to sustain the machinery of the band. There wasn’t a label behind us or advances we could draw on against the future. We weren’t in that position. We were self-funded.

The Bears, 2007: Chris Arduser, Bob Nyswonger, Adrian Belew, and Rob Fetters | Photo: Michael Wilson

The Bears, 2007: Chris Arduser, Bob Nyswonger, Adrian Belew, and Rob Fetters | Photo: Michael Wilson

What do you consider the highs and lows of The Bears?

The high is that I thought I was living in a dream world. It was so much fun to be in that band. The first Bears tour involved me playing electric upright bass, which I had only picked up that year and I wasn’t terribly great at playing it. I certainly knew people who really knew what they were doing on the instrument were probably looking at me going, “How did he get that gig?” [laughs] But by the end of that tour, the band was in great form. When we played The Ritz in New York City, there were hundreds of people who couldn’t get in. Mick Jagger was in attendance. It was surreal. It was so exciting.

The low is the frustration I came away with from the first run with The Bears in the 1980s. I wondered if it was just a tax write-off for Miles Copeland who ran our label PMRC. I didn’t feel like we got the push we should have. I’ve spoken to so many people who went to our shows in the 1980s that said they were memorable and really inspiring. And that is so gratifying, but we thought the possibilities should have been bigger for the band.

I still remember halfway during the Rise and Shine tour, the plug got pulled on the band by the label. We were playing clubs, filling them constantly, and wondering “How do we take it to the next level?” But we never got that chance and that was effectively the end of the band.

Could The Bears reemerge?

I would never say no to anything. Chris has only been gone for more than a year, so that’s still kind of raw. But I’d love to do stuff with Rob and Adrian again. I’d love to go out and reprise our five-album career and have people enjoy that. That’s kind of what Adrian is doing with Beat when it performs the 1980s King Crimson material. There’s a market for that. People love to hear the music that was important to them when they were younger.

I think we could execute the music properly and bring the right spirit to it. It’s hard to think about doing it without Chris, but I know there are a lot of great drummers that would love to do it. So, I’m not going to close the door on the possibility.

The Raisins at Bob Nyswonger's home studio, 2024: Bam Powell, Rob Fetters, Nyswonger, and Ricky Nye | Photo: Michael Wilson

The Raisins at Bob Nyswonger's home studio, 2024: Bam Powell, Rob Fetters, Nyswonger, and Ricky Nye | Photo: Michael Wilson

The Raisins are an active unit again. What did the 2024 reunion gigs mean for you?

It was really fun bringing those songs back to life. I’m proud of that music. It doesn't sound dated to me. Everybody had a good time, and it was also profitable. It was also great to get reacquainted with Ricky Nye again. As far down the boogie woogie alley as he’s gone, he still has that rock stuff going on in his head and he really came through for the shows.

We all felt like the last show we played during the reunion gigs in November 2024 was the best one The Raisins ever did in its entire career. We did a lot of great shows 40 years ago, but in terms of everybody’s skill level and being conscientious and focused, it probably was the very top one.

We played more than 30 songs a night on average during these shows. And “Porkopolis” is really three songs in one. It went back to what the band was about. We always had like 70-80 original songs ready to go. Every night, we’d pick and choose what we wanted to play.

We used to have this embroidered setlist. Ricky’s late ex-wife would embroider one or two new songs on it every month. Eventually, it transformed into a Dead Sea Scroll or something because it was so long. It became very important.

The response to the shows was fantastic. It’s a testimonial to the fact that this music was important to these people during a formative time of their lives. Some of them brought their kids. There were a lot of younger people there. It was a nice blend of generations.

Everybody had so much fun that we’re going to do more shows and maybe play even more weird songs we haven’t played in a long time. We just want to work smart and control all the parameters of future gigs, so we have good sound and organization.

Provide some insight into the making of The Bends documentary on The Raisins.

Mike Tittel came from the advertising world and really knows how to frame things well. He’s a longtime fan of the band and did a great job of distilling everybody’s thoughts and feelings about The Raisins. He created a very interesting narrative. It starts by leading up to the first reunion show and then he does follow-up interviews three months later. I think it was a cool way to do it, and it worked out well.

The Raisins situation is unique in that since we broke up 40 years ago, we’ve really all gone our separate ways. There have been a handful of reunion gigs over those decades, but the shows we did in 2024 were a significant regrouping compared to those. The fact that everyone got together, got along, and tried to do something positive was special. We’re also all free agents and can do whatever the hell we want. None of us have contractual obligations.

I think the chemistry of the reunion was a revelation for Rob. He’s been doing solo shows on his own for a long time. The reunion shows reminded him of the value of being in a band, as opposed to being in control of everything. He’s got some Jeff Lynne tendencies. I'm more laissez-faire in comparison. I think Mike captured the contrasts well.

The other thing I like about the documentary is it's all new interviews and footage. Mike didn’t cut back to any of the old footage, like the Rock Around the Block film from 1980, which is the best production-quality video of the band during its heyday, but it was before we had Bam. Sadly, that band from ‘81-’85 was never well documented on video. Obviously, nobody had cameras in their phones back then either.

The film really is accurate in how it captures our different views on the band while keeping things overall positive. There was an early cut of the film in which Bam and Ricky were a little resentful about the fact that Rob and I went on to do national work with The Bears after The Raisins. And if I was in their shoes, I would have felt the same way. But The Raisins didn’t break up so we could go and do that. Rather, Rob said, “I’m done. I don’t want to do this anymore.” And it was only after that when Adrian Belew said to Rob, “Maybe we should do something, then?” The band was essentially done.

I like the fact that the final cut didn’t focus on that kind of stuff. All kinds of stuff happened at the end of the band, but looking back, it’s not important. The fact is the band had run its course.

After the breakup, I was the one who put together the Everything and More compilation. I worked hard on the audio to make it sound consistent from song to song. It was a monumental project, but I thought I owed it to the band, because I was so proud of our work. I wanted it documented. I’m happy that it's still out there, as well as Mike’s great film.

The Raisin Band, 1976: George Leist, Rob Fetters, Diane Bressler, Bob Nyswonger, Vaughn Turley, and Steve Athanas | Photo: Mick Athanas

The Raisin Band, 1976: George Leist, Rob Fetters, Diane Bressler, Bob Nyswonger, Vaughn Turley, and Steve Athanas | Photo: Mick Athanas

Let’s talk about some pre-Raisins history. The first version of the group was called The Raisin Band. Reflect on that period.

I was playing with Rob Fetters for a couple of years towards the end of high school. We had a band called Red Hot Tots that worked school dances and frat houses. He also played with us in Legs, another band I had with Chris Arduser, earlier on.

Rob was attending Ohio State University and decided to bounce out of there to pursue music full time. He hooked up with Steve Athanas, who was a little older than me. Steve and Rob put together Strongheart, which had Dianne Bressler on vocals, a keyboard player, sax player, and drummer.

When I graduated from high school—a year after Rob—I spent the summer of 1973 playing with Johnny and the Hurricanes. Johnny Paris was a Toledo guy with a pro gig. It was an eye-opener. We had to wear matching shirts and we’d play things like the Wisconsin State Fair. It was a fun, interesting summer for me. Then I attempted to go to Ohio State University to study liberal arts for a couple of quarters.

I heard Rob had this new band Strongheart. They were working clubs playing four nights a week. I got busted for weed in January 1974 and then transferred to the University of Toledo that spring, again studying liberal arts. As soon as I arrived, I was immediately looking for someone to play with. By that point, Strongheart had kind of blown up and they were going to create a new band. I was invited to play bass. They changed drummers and keyboard players, and the new group had Steve, Rob, and Diane singing.

They called it The Raisin Band. Steve came up with the name. There’s no rhyme or reason for the word raisin in the name.

We played the hits of the day from the likes of Steve Miller, Steely Dan, and J. Geils Band. We were a cover band at the beginning. We could do some vocally-intense tunes like “Pretzel Logic,” “China Grove,” and “Rocky Mountain Way.” We even made a demo tape of all cover tunes just for booking, which was my first experience in the studio. It was at a low-budget place called Hanf Recording.

We aspired to do our own stuff and eventually started writing songs.

The Raisin Band also recorded an album-length highly-polished demo of original songs. What can you tell me about those sessions?

We did that in 1975 with a bunch of tunes which were mostly written by Steve and Rob. I had a few on it too, including “Nudies Gone Berserk.” Steve wrote the words for it. I was trying to come up with something that sounded like Utopia. It also had tunes like “I Don’t Give Up” “Mexico,” and “Lost in the Sauce" on it.

Soon after, the personnel of the band started changing. A lot of people came in and out, and by 1976, the drummer and keyboard quit. That’s when Rob said, “Let’s get Chris Arduser if we can.” Chris wasn’t out of high school yet. So, Rob talked to Chris’ dad, who was a dentist, about how he didn’t need to finish high school and that he should come out on the road and be a rockstar. [laughs] We weren’t rockstars, but that was the fervent hope.

Chris chose to join, which was great. I had played with Chris since he was young and knew he was capable of playing anything. He was such a great musician. Tom Toth also joined on keyboards in that period. Both Chris and Tom were in a group called Allsmall Band, which I played with occasionally, too.

At the time, I had no permanent address. I lived on the road for two years. Even when we were in Toledo, I stayed in a hotel or with friends. That’s how weird my life was at the time.

Bob Nyswonger and Bam Powell perform with The Raisins, 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

Bob Nyswonger and Bam Powell perform with The Raisins, 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

How did The Raisin Band transform into The Raisins?

What happened is Chris Arduser, Tom Toth, Rob Fetters, and I realized we had enough strong singers and didn’t really need a frontman for the songs we were writing. Steve was a great entertainer, but we wanted to double down and focus on writing and recording. And that’s what happened. So, in early ’77 the four of us shortened the name to The Raisins, relocated to Cincinnati from Toledo, and refocused our energy.

Again, we didn’t have permanent residences and were drifting around Cincinnati. Our management was there, and the gigs were better as it was a bigger city. Our management also got us into better studios. We mostly worked at Fifth Floor Recording, which is where we made our first recording, “Your Song Is Mine.” It was released on a WEBN compilation. We eventually shifted our recorded work to QCA, where we recorded our self-titled 1983 debut LP.

What do you recall about making “Quarters,” the first Raisins 7” single in 1981 on Raisin Records?

That was just after Bam Powell joined the band. It was done on an eight-track recorder at Northside, at a primitive studio above a costume shop in Cincinnati. The song cut together the intro from a live version with the studio recording. And that was our first single. We used the same version on Everything and More. We basically did it for fun.

Tell me more about Legs and Allsmall Band.

Legs was a band I was in during high school between ‘70-’73 that was formed by a guitarist named Doug Perkins, who was also in Red Hot Tots. It also had Chris Arduser and John Arduser in it. I didn’t play bass in it, originally. There was another bass player and I was just the lead singer.

We were all Alice Cooper fans. We’d put on makeup and make a big show out of our gigs. We also had some original tunes that were primitive and awful. We wanted to be kind of like Bonzo Dog Band and The Mothers of Invention—weird, outrageous, and fun.

Allsmall Band was a group Chris got together to do very complicated music in 1975 and it lasted through 1976. It was a prog-rock monster. Chris hooked up with Tom Toth, Roger Holland, and Dick Lang. It had two guitarists, bass, and drums. The first time I saw them, I was totally blown away. It was obvious it took a long time for them to put their music together. It was so well-rehearsed and impressive. They were kind of like a combination of Mahavishnu Orchestra and King Crimson with a little bit of Allman Brothers. They were 16-18 years old at the time.

I wanted to be in that group, but I had a pro gig with The Raisin Band. However, I did play ARP 2600 synthesizer with Allsmall Band a few times. I also worked with them on the soundtrack to a short student film called Technilepsy that you can see on YouTube.

Allsmall Band would frequently have like five-to-10 solid musical ideas welded into an eight-minute piece. And you can hear some of those elements on the early Raisins demos we did with Tom. He was amazing at having three or four fragments of good pop songs come and go all in three minutes.

The Chris and Tom version of The Raisins did some demos with Adrian Belew back in 1977. We had met him at that point through our management, right after he joined Frank Zappa. At that time, Adrian moved from Nashville to Springfield, Illinois and was working in a studio called Kwazy Wabbit with Rich Denhart, the engineer.

We recorded tunes like “Stella,” “I Don’t Give Up,” “Mass Media” and some other Tom songs with Adrian. He was interested in producing the band back then, which he eventually did in the early ‘80s.

Technilepsy generated quite a bit of attention when it was released in 1976. What do you recall about working on it?

A friend of mine named Ken Raymer directed that. He was a cinema major at Ohio State. We were both tripping hippies at the time. One day, Ken told me about this film project he wanted to do, and he had heard Allsmall Band and asked if they could do the soundtrack. The film was a collection of NASA footage and stuff he shot himself. It also included some early computer graphics that were cutting edge then.

Once he had a cut of it together, he brought it to Allsmall Band. All of us kept looking at the film wondering what the hell we were going to do for it. Ken really wanted some synthesizer on it, and I had an ARP 2600. So, I played that on it.

I have no idea what the film communicated, but it won a Student Division Academy Award for short films. I think the soundtrack probably had a lot to do with that, because it was original, interesting music.

In 1985, every member of The Raisins participated in the making of The Biscuits’ LP Gorillas on Display. What’s the story behind it?

It was basically an excuse to get together and party. The guy that instigated it was our soundman, George Corneliussen. He said, “I want to do something with my songs.” So, we learned them, he recorded them, and pressed them up. We even played two or three gigs.

Everything was done piecemeal—a couple of songs here and there when he had money to buy studio time. George is very proud of that record. It was a big deal for him, going from being someone who worked for the band to becoming the director for this album.

George had also got some video cameras from a public access TV station. He recorded the sessions as best he could. I remember during one, we were all pretty stoned, and Bam Powell is the frontman. We did a send up of an R&B thing that was psychedelic. Some of this stuff is up on YouTube.

Photo: Mike Tittel

Photo: Mike Tittel

How has your bass playing approach evolved over the decades?

I got my technique together when I was a teenager. I had figured out the physical limitations of what I could play and how many notes I could cram into a measure. As I got older, I became less focused on displaying technical prowess. I also evolved into being a fretless player. In Tickled Pink and Bucket, I only play fretless. It forces me to play differently. I had to adapt my thinking to that instrument.

In the early days, I would manage to really put a lot of notes into a song. When I was learning how to play bass, John Entwistle, John Wetton, John Siegler, and Jack Bruce were big influences. When I first picked up the bass in 1969, I played with a guy who said he wanted to play Cream material. He gave me the LP Goodbye Cream and asked me to learn “I’m So Glad.” It’s only two chords, but I realized there was a lot more happening than those chords. So, I learned from Jack how to embellish and create interesting parts.

When it comes to bass playing, it’s not that you’re harmonically limited. Rather, you’re limited to what your physical capabilities are and what you can hear and make work. So, my technique has evolved in that I’ve become better at thinking of something or hearing something, and then being able to play it.

I’ve also become a little bit more of a soloist, particularly in Bucket. I didn’t really know how to do that until I started playing in that band. I’ve mostly been about driving the rhythm and framing out the song. So, soloing was the last frontier for me, and I feel I now know what the instrument’s all about and how to interface with it.

What’s your perspective on the state of the music industry?

Don’t quit your day job—that’s my perspective. We just keep putting out music with all these bands, independent of the state of things.

It would be great if somebody said, “Hey, I’d love to use that ‘Trust’ song by The Bears” in a film, TV show, or ad. It’s about the only way to make money from a song these days and get any mechanical royalties for it. Otherwise, it’s now almost impossible to make money from recorded music.

At some point, the tech middlemen came in and hijacked the business. That’s a fact. And they’re trying to do it in every industry and they’re succeeding. If you can write really good software or build a platform, that’s where you make money.

Like we were discussing at the beginning of the interview, music doesn’t have the same cultural impact or importance as it used to for people. It may affect people in profound personal ways sometimes, but it doesn’t occupy the same mind space—you know, the days of waiting months for the next Who album to come out. Then you get it, study it, and play it endlessly. I don’t see people doing that so much now.

Rather, music is in the background somewhere. It’s not the focus. I don’t think kids get friends together and sit around listening to new records and digging deep. I think that’s reflected in how music is now monetized by the tech middlemen.

So, if you’re going to be a musician, you better have another source of income in mind if you want to survive in this world.

I’m still happy to record and bring what I can to the work. I’m really proud of the records I’ve made. I feel I continue to improve in terms of my songwriting and bass contributions. As long as I get to play, I’m happy. The tech middlemen can’t get in the way of those things.

You’ve spent most of your musical life based out of Cincinnati. What makes it your anchor point?

I think with this scene, what you get out of it is what you put into it. And we put a lot into it, in terms of the music and developing relationships with people, including musicians and listeners.

I’m able to go into venues and say, “Here’s what I’ve done.” They might tell me to pound salt, but a few of them say, “Well, come on in, and let’s see if our crowd will be into it.” So, as long as people are willing to come out and make you a part of their evening, the venues will respect that.

The truth is the money you make playing bar gigs in Cincinnati is the same as it was 20 years ago. If you can go home with $100, you do it. And I still do a lot of those. I do it because I want to play. It’s a part of me. It’s what I enjoy doing. I don’t do it to sustain myself economically. I do it to sustain myself, spiritually.

We’re so lucky to have a real community here. When I was on tour with The Bears, I saw a lot of cities. I thought I might come out of that going, “You know what? Cincinnati may not be the best place to live. Maybe there’s a better place.” But I never left.

I’ve never found anywhere I want to leave Cincinnati for. I feel most at home here. It’s a big enough city to support what I want to do, and a lot of people appreciate it. So, that’s where I’m at. I’m lucky to be here. And I’ve been lucky my whole life.