Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

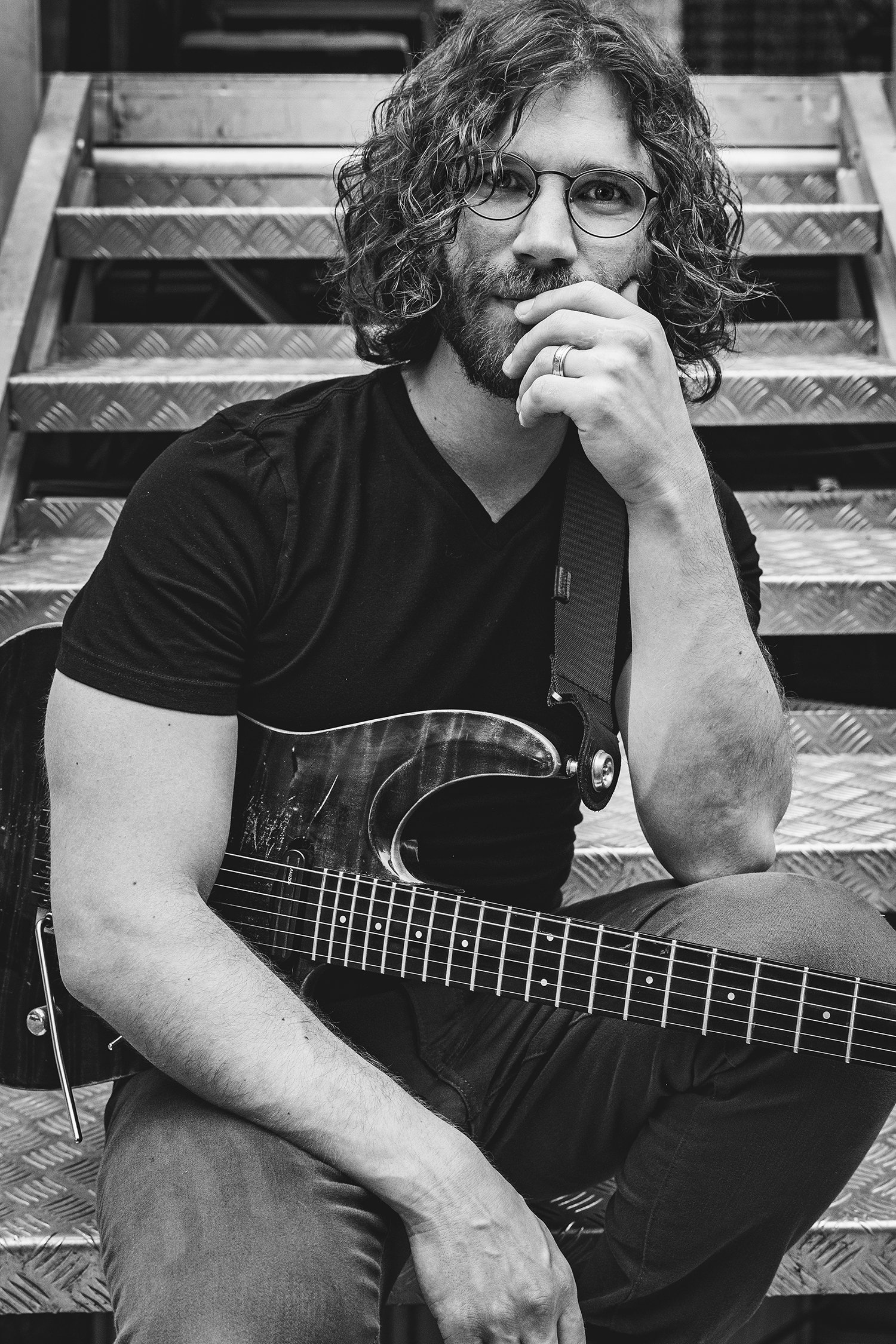

Randy McStine

Ground and Sky

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2024 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Hajo Müller

Photo: Hajo Müller

Singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Randy McStine’s career journey is informed by drive, grit, serendipity, and an unwillingness to compromise. It’s why his expansive rock output has achieved global renown across circles of discerning listeners and musicians entirely on an independent basis.

The American musician is best known as the touring guitarist for Porcupine Tree during its 2022-2023 reunion tour, as well as his contributions to the 2025 Steven Wilson studio album The Overview. But what newcomers view as a rapid emergence across arena, festival, and large theater gigs, is actually the result of hardcore perseverance that began in 1998 at age 10.

McStine started out as a prodigiously-talented child guitarist, writing and recording instrumental rock compositions inspired by the likes of Joe Satriani and Gary Moore. In 2009, following several early solo recordings, he chose to explore wide-spectrum singer-songwriter possibilities under the project name Lo-Fi Resistance, yielding three studio albums and a live release.

Lo-Fi Resistance offered intelligent, kaleidoscopic songs that straddled progressive rock and atmospheric pop. Several major musicians took an interest in the work, resulting in the participation of drummers Nick D’Virgilio and Gavin Harrison, bassists Colin Edwin and John Giblin, guitarist John Wesley, vocalist Dug Pinnick, and violinist Joe Deninzon.

Since 2016, McStine has focused on recording and performing under his own name, releasing more than a dozen studio and live efforts. He has also engaged in two major collaborations: The Fringe, a power trio with D’Virgilio and bassist Jonas Reingold; and McStine and Minnemann, his avant-pop duo with drummer Marco Minnemann. McStine also went on to record and tour with the likes of Jane Getter Premonition, Stu Hamm, Adam Holzman, Vinnie Moore, and Ryo Okumoto.

McStine’s new solo album, Mutual Hallucinations, is an encapsulation and extension of his diverse directions and experiences to date.

Sessions for the LP extended over the last five mercurial years, which included both the COVID-19 pandemic as well as McStine being recruited for Porcupine Tree. McStine harnessed the possibilities of the evolving environments to his advantage, revisiting and reworking the material until he hit his creative stride.

He describes the approach he took on Mutual Hallucinations as a search for “ground and sky,” referring to a desire to take his observational, timely songs and situate them within ambitious constructs that shift between the accessible and avant.

It’s also an all-star effort, with appearances from D’Virgilio, Harrison, Holzman, and Minnemann, as well as drummer Pat Mastelotto. Mixing duties were split between Wilson and Tim Palmer. Even more impressive is the breadth of McStine’s own performances, with him handling vocals, guitars, electric sitar, ukulele, bass, keyboards, drums, percussion, and programming.

McStine began his conversation with Innerviews by exploring how sociopolitical flux, disinformation, gaslighting, and false flags served as catalysts for Mutual Hallucinations.

Randy McStine live at Yoshi's, Oakland, CA, October 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

Randy McStine live at Yoshi's, Oakland, CA, October 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

What are your thoughts on the value of music during this era of such polarization and chaos?

On an individual level, it has great value and is deeply personal to me and the types of people I work with. Culturally speaking, there is a difference. When I look backwards at the history of music, I see these pivotal moments during which music, culture, and politics combined into mythic moments. But I’m not able to see whether or not, in 2024, if we’re living through anything similar. I don’t know if any pop artist has put something out that is significantly influencing the world at large or is intersecting with broader culture.

These days, generally speaking, with the arts, you have popular shows, movies, and music, and everything has its specific audience. But there are few things I think reach everybody like things seemed to in the past. There are just so many options today and so much competing for our attention. So, from an individual level, I know what music means to me. I know that I continue to search for new music and music from the past that has value.

On stage, there is something different that happens. I’ve been in many situations in which I’ve thanked the audience for being there, and for coming together under the banner of enjoying the music and having a connection through it. It’s a place where everyone can put aside their differences for the evening. There is a point of commonality, which is great. So, we still do have that.

Discuss how Mutual Hallucinations addresses the themes of tribalism and self-delusion at the expense of legitimate truth and facts.

The album title refers to the idea that we’re sharing a space in which algorithms and politics intersect and divide us into hyper-individualistic perceptions of the world. We’re all walking around with a different take on what the world even is, much less what’s happening in it. It’s a hallucination of sorts.

What I think happens these days is we try to form a sense of everything that’s going on, and mostly converse with people who land on the same side of a particular issue. These are the people we band together with. But it’s all happening within a vortex of information and disinformation. The distinction becomes “my truth” and “your truth.” So, Mutual Hallucinations is about how society has crossed the point to arrive where we’re together and completely apart, simultaneously. It’s also about the things we’re ignoring at our own peril.

Let’s explore some of the album’s key tracks, which relate to the larger narrative, starting with “Counterintuitive.”

Structurally, the song started as a ukulele solo vocal piece. I barely know what I’m doing on the instrument, but I can move around and find shapes on it. So, you’re hearing me play ukulele and singing as a full take, with the rest of the track built around that.

Lyrically, it sets up the record with a somewhat cynical tone, but it’s observational about how for humans, even when something is clear as day in terms of what we need to do, individually or collectively, we so frequently decide to go completely in the opposite direction.

There’s a line in the song that goes “If the universe told us it’s run out of ways to provide, we’d blow it up to salvage our pride.” That’s referring to the idea that no matter what, we’ll take something given to us on a silver platter and just flip it over, because it just seems to be in our nature.

Talk about the specific element of American societal breakdown “Economy of Differences” examines.

The track is a response to the mass shootings we have in the United States. I woke up after one of them and felt the combination of feelings most sane people have, which is hopelessness at the situation, and anger at the fact that no matter what happens, we can’t get to a point in which we’re willing to figure out how to stop them from happening—or at least attempt to curb them, without so many people immediately rushing in to hijack the conversation for their own benefit.

In the song, I tried not to point fingers at any side of the debate. I always try to do that with my commentary in songs. Rather, I present things as I see them, but leave it open to listeners to reflect on what’s being said, and to hopefully have them see themselves within the dialog.

“Remains” closes the album with further consideration of how we’re manipulated into stark divisions across every online touchpoint. Describe what it looks at.

It was the first song I wrote and completed during the COVID-19 lockdown. I wrote it a couple of weeks into it, around April 2020. Lyrically, it was my response to living through that moment.

It reflects the fact that we were fighting amongst ourselves about whether or not going outside was a good or terrible idea. And the communication in America that was coming from the top down to states and local governments was a total nightmare. It was completely mind-blowing during this period when we were united in the unknown. At the time I was writing the song, we had already arrived at a point at which we were fractured as a society.

People were forming binary ways of looking at the situation. So, it was symbolic for me to close the album with essentially a similar thread as where the album starts with “Counterintuitive.” Together, they form a kind of 360-degree view of the perspectives the album communicates.

Some academics argue civilization as we know it was always a fabrication. The perspective is the 20th Century was the apex of our veneer of civility and that the species is simply reverting to what it really is at its core. What are your thoughts on that?

What you’re saying kind of describes the end of “Counterintuitive.” In it, I communicate that after we blow ourselves up, even if we start again from the ground up, we’re going to repeat the cycle. We’ll begin a new loop involving picking some idiot to try to run the world and having the same outcomes. It’ll just be a question of how long it takes to happen.

So, the album is not an entirely optimistic take on things. It’s hard for me, at this point in time, to see a more positive outcome, especially with the very advanced technology that we continue to add into the mix of the species that always further confuses things.

Randy McStine at his home studio in Broome County, NY | Photo: Avraham Bank

Randy McStine at his home studio in Broome County, NY | Photo: Avraham Bank

You spent years working on this album. What informed the time horizon?

Every time I make a record, I feel like it’s a journey through process. This one needed time to figure out what it wanted to be. I had a lot of ideas in various stages of completion for a long time, but I wasn’t sure where they were going. So, I’d find myself getting away from it all for long periods of time and then going somewhere else. I’d come back to it when I felt I had something new and interesting to bring to the table. I also wanted to find things that were surprising to me.

Now, when I listen back to it, I hear a sense of mystery in it, and I don’t actually even know how I accomplished some of what I did on it. There was stuff that happened in the moment when I was in the zone. And that’s a feeling I live for.

I think the album benefited from the fact that it took the longest from start to finish of any of my albums. It gave me perspective on what I was trying to do. I think where it landed is an amalgamation of the singer-songwriter leanings I’ve had in the past, mixed with my experience in progressive circles. It reflects a much deeper understanding of production and arrangement.

Did the fact that you’re known by more people because of your association with Porcupine Tree influence the creative process?

I’d be lying if I didn’t acknowledge that it made me want to create something that could play at a bigger level. So, I paid a lot more attention to detail when making it.

I stand behind all the work I’ve done previously. All of it was the best I could do at that moment in time. Whenever I release something, it’s because I felt it was good enough for me. I’ve tried to keep that bar very high. And I think the past couple of years has created pressure to level up my work. I’m not trying to cater to anyone, but I do want to present something to the audience that I feel is worthy of its attention. This process had very little to do with the idea of selling it to anybody. Rather, I had to sell myself on it.

Steven Wilson mixed several tracks on the album. Discuss his influence on the outcome of those songs.

Steven and I have been in constant communication since the last Porcupine Tree tour in the summer of 2023. At one point, I was feeling a bit stuck when making this record. I had completed the song “Adopted Son” and asked him if he’d be willing to consider mixing it and he agreed. When he got in there, he discovered that for him and his tastes, there was too much musical information in it.

When Steven sent it back to me, he left me a note saying he threw a bunch of stuff out and that I should sit with it and see what I think. I thought he made it a million times better. He was absolutely right, not just because of his pedigree as a mix engineer, but also as a writer and producer himself. He was able to see the bigger picture better than I could. It taught me that I tend to overcompensate with too many ideas, when the fact is less ingredients can make the dish taste better.

This was a turning point for me. After that, Steven and I got into a back-and-forth rhythm with a few more songs. This gave me the confidence to finally get the album done. Everything started moving very quickly and I finished up all the in-progress songs, buttoned them down, and sent them to him. Luckily, he had a gap in his schedule during which he could prioritize this work, which I’m very grateful for. In the end, he mixed half the record for me.

Photo: Avraham Bank

Photo: Avraham Bank

What’s your philosophy when it comes to directing musicians who perform on your music?

My records reflect my interest in getting better as a musician on all fronts. Yes, I’m known as a guitarist and singer, but I really care about my bass playing and textural ideas. I simply want to hear myself expressing what I can do on those instruments. So, where things usually land is I play most of the things on my records, and then I get different drummers involved.

Even though I love playing drums, it’s the one position I feel I can’t make happen in the way I want to hear. So, I’ve been very fortunate to get to know and work with a lot of great drummers. This record has Pat Mastelotto, Gavin Harrison, Nick D’Virgilio, and Marco Minnemann on it. I did play drums on one song called “Impossible Door,” because I felt it was a piece I could support with my abilities.

I also have Adam Holzman playing keyboards on a couple of tracks. He’s brilliant and brought in so many things I couldn’t do on my own.

In terms of directing the musicians, a lot of it is unspoken. It starts with having a player in mind that I think will naturally guide the track towards what I have in my head.

When it comes to drumming, it’s typical for me to program some drums as I’m building the tracks. And then once I get the bigger vision together, I’ll bring in a drummer. They tend to get involved as the tracks get close to completion. But pretty much every time, what they kick back to me influences how I finish the rest of the track. Sometimes, I’ll reassess elements to lock in with what they’ve done. They’ll reveal things through their playing I wasn’t aware of, initially.

I admit, it’s kind of weird when you’re not making music in real-time with somebody. The communication part has to happen in stages, because you’re listening to something that has already happened in the past. In essence, someone is contributing to a static form of expression. When I get parts back, I have to bridge together different performances and make it feel natural.

How do you overcome option paralysis as a multi-instrumentalist?

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to not be able to play different instruments. But that’s impossible to know even though it seems like things would be easier. By that, I mean all the attention could go to those one or two things I specialize in. But if that occurred, there would be multiple musicians involved in every position and the whole sonic stamp would change.

I try not to get too bogged down in option paralysis. In terms of this record, it’s unique in that I tried to largely craft sounds on physical instruments. There was very little use of software synthesizers.

During the first Porcupine Tree tour I did in 2022, one of the most inspiring things to me was watching Richard Barbieri every night. I was closest to him on stage, and whenever I wasn’t playing, I’d pay attention to what he was doing. He’s such a genius at synthesis. He creates these sounds that are completely previously unheard of. That got me into wanting to build up more of my physical keyboard arsenal and to work with things that are more tactile, rather than pulling up preset sounds and tweaking them.

I said to myself, “You’re going to build sounds from the ground up and see where you end up.” So, Richard had a huge influence on my approach. Doing things this way does take a lot of effort. I’ll spend a lot of time looking for a sound. Sometimes I’ll find it immediately, and other times it’ll take hours because I’m not quite sure what I’m looking for. But I have to allow myself to have that time. The danger, however, is spending too much time doing that stuff, and getting exhausted, without getting any “real” work done. But I really wanted to go beyond my comfort zone and push myself to find new ways of doing things.

I do think this record is very stylistically diverse and doesn’t belong to any particular genre. But there’s something about the way it holds together that I feel is very cohesive. I believe it’s my most realized work to date. It has a listening arc that enables people to bounce between the different sonic worlds each song inhabits, without feeling like they’re on a crazy rollercoaster ride.

Despite your increased profile, you had some unhappy interactions with record labels who were considering releasing Mutual Hallucinations. You ultimately chose to put it out independently. What did you experience?

I grew up with the whole record label dream since I was a kid making independent records and playing gigs. The idea was you’d play somewhere, get discovered, and move on up the food chain. It’s the naïve idea most musicians used to have. But the fact is, my ability to remain independent during the Internet era is largely responsible for the career I have. It’s why I’ve got to work with so many musicians and join the bands I have.

I was born and raised in a small upstate New York town. I still reside in one and it hasn’t kept me from doing the things I’ve set out to do. I have increased awareness, I’ve met a lot of people in the industry over the years, and I get to play with musicians who tell me they have a tremendous amount of respect for me as an artist.

However, at the end of the day, there’s still resistance from the music industry about the fact that my music is not easily categorizable and that it “falls between too many musical chairs.” I’m told it’s an artistic success, but a marketing problem. So, until a label steps up to the plate and accepts my work for what it is and can engage in creative marketing to find a larger audience for it, it doesn’t make sense to keep trying for one.

The people that listen to my music are the same as me. They’re people who aren’t caught up in categorizing the music. They just want to listen to it as a piece of art. So, I remain independent for the time being.

The fact is everything with labels is now geared towards analytics and metrics. They go to the streaming services, YouTube, or Instagram and look at the numbers. They want to know how many people follow you, how many streams you have, and how many views they’re generating. If they don’t see a metric they like, they won’t even click play on your music. It’s an unfortunate situation.

On one level, I understand why things are the way they are, especially given the amount of music pushed out daily, along with every other cultural form. But where it gets unfortunate is when there is quality work out there that won’t get a single honest look, because all they’re looking at is analytics.

I admit it’s disheartening for me, because I’m not a completely unknown person. I don’t have a commercial history with these big metrics, but there are enough people who know my music that I’d think a label could at least look at a biography and have a quick listen. But that’s not how things work any longer. The labels don’t seem to have even a base curiosity about the music or artistry. It’s about whatever is going to immediately and easily sell.

I don’t know what this means for the future of a lot of artists, other than trying to create a dedicated fan base and organically building it up from there. It’s a very kind of grassroots, old school way of doing things. But it has worked for me so far. The big machine doesn’t seem to work for me at the moment.

Photo: Hajo Müller

Photo: Hajo Müller

Let’s dig into how you built up your audience in more depth.

Historically, I’ve been inconsistent in my outreach approach. I typically put all of the time and effort into the work itself and then would be a bit shy on the promotion part. I think why I was attracted to the idea of working with a label is that it would let me focus on art, and they could be the mouthpiece for it. But that’s not the way things work any longer.

Social media is such a force now and all artists are expected to use these tools to constantly promote themselves. You have to be careful and walk a tightrope, so you aren’t oversaturating your message, but showing up enough for people to know you exist. That’s the ebb and flow I’ve worked with over the years. But ultimately, I believe live performance is where word of mouth has really spread.

The more I’ve put myself out there in a live context, the more I’d start seeing familiar faces showing up. I’d befriend a lot of people and build a coalition of people from the ground up that care about my work and are interested in what I’m doing next.

I’d say 2019 was a turning point. I really started putting my foot to the gas to not just be seen as a sideman, but as someone stepping out on my own terms. I had an electric trio that year that did shows. I also had an opening slot for The Pineapple Thief in North America. That went very well, and the audience was very receptive.

Of course, the COVID-19 pandemic came in shortly afterwards and blew everything off course, but it did prove to me that I could get my message across to the people that were there to receive it in a live context.

I learned about you from fans who insisted I listen to your music. What are your thoughts about the network of people that have emerged to support and promote you?

Oh man, I have immense gratitude to those people. They’re the ones that have convinced me that what I do is worthwhile, especially when I experience a really down moment in which I start to question my own worth in the music world at large. There’s always an inevitable moment when I’m working on something and I think it’s great, but self-doubt always emerges and that voice can pull back at your potential if you give into it.

Talking to someone who really gets the work, really believes in it, and can’t wait for the next thing you’re doing can really lift you out of that situation. It’s a real course correction to realize you do have people who are invested in what you do and that it would be a disservice to not keep bringing your art to the table. The desire to create and share art is something truly unique to our species. That can also be a nerve-wracking process, because your art can be interpreted multiple ways, or misinterpreted. But you have to let it go out there and live its own life once you set it free.

Your debut album Shredding Skin was made at age 12. Discuss your early days as a recording artist and performer.

When you’re young and haven’t lived much life, your biography is all about what you’ve done in the last year or two. And as you keep going, those years become footnotes and don’t even get mentioned any longer, which is the case for me.

I got an electric guitar for my fifth birthday and fiddled around with it for a year before I started taking guitar lessons. Between 6-10, a vocabulary emerged in my guitar playing. It was mostly a blues-rock vocabulary. People around me felt I had something special happening, so the next step from the bedroom and guitar lessons was to start sitting in with local bands.

I was kind of thrown into the deep end with no prior experience playing with anybody. It was through doing those shows that a lot of musicians realized I could play and communicate musically with people on stage. Those experiences began growing and unfolding. We’re talking about when I was aged 10-12.

I was already regularly gigging that young. I learned tons and tons of cover tunes and was mostly playing classic rock, blues stuff, and instrumental rock. By age 12, the next step seemed to be that I should record an album.

By the year 2000, I had my own instrumental tunes. My dad wasn’t a musician, but was a big music fan. He’d have musical ideas that he’d hum into a tape recorder, and I’d learn them on guitar, and we’d put these songs together. And that’s what you hear on Shredding Skin. There are a few covers on it, including Jeff Beck’s “Freeway Jam,” along with Joe Satriani and Gary Moore tunes. The rest are original compositions that I wrote or co-wrote with my dad.

My dad booked a little studio outside of Cortland, New York for a couple of long weekends. We recorded the album Shredding Skin and independently pressed up CDs and sold them at shows. Another album followed at age 14 called Second Shot. It was in a similar direction, but my writing was a little better by that point. Soon after, a label called Grooveyard Records found out about me and put together a compilation of those two CDs with a few new tracks called Guitarizm.

The reason I’ve expunged these records for the most part is because I wanted more control over the entry point through which people find out about me and my work. I didn’t want those early albums to get priority in Google searches over all the other work I’ve done since, which is miles away from that era. I don’t want people who look me up to think of me as the kid that made Shredding Skin. For instance, I remember meeting Kerry Livgren for lunch once and I realized that his context for my work was what I did at age 14. I felt, “This can’t happen again.”

Those albums are curiosities at this point. They’re for completists. They’re the beginning of my journey. If anyone finds them, the caveat is you’re listening to a kid in his early teens. They have nothing to do with the music I make now.

We’re only talking about eight years between Shredding Skin and me starting Lo-Fi Resistance at age 20, which was the real beginning of my professional career. I felt I needed a clean break so I could start that new musical journey. Using the name Lo-Fi Resistance for my music was a way of creating a line between those early albums and what I was doing as an adult.

Photo: Avraham Bank

Photo: Avraham Bank

How do you look back at your output under the Lo-Fi Resistance banner?

I view the first two albums as Lo-Fi Resistance as a musical rebirth. I was moving into my next phase as a musician and songwriter. I had exited my teens and wasn’t sure what my place in the world of music was going to be. Opportunities and promises related to my early music never came to pass. So, I wasn’t sure If I was going to continue as an artist. I thought perhaps I could go into production or engineering.

Eventually, I realized I just had to make music for the sake of making it, independent of any idea of trying to “make it.” The first Lo-Fi Resistance album, A Deep Breath, was a collection of recordings I made in an apartment I was renting. I played multiple instruments and really experimented with the possibilities of playing everything on a track from top to bottom.

With Lo-Fi Resistance, I was channeling new musical influences including Cocteau Twins, Jeff Buckley, Bill Nelson, and Crowded House. So, the first album was a stylistic roller coaster with power pop and progressive rock influences.

When making A Deep Breath, I also started thinking about who I would love to have play on my music. I thought Nick D’Virgilio would be a great drummer to have on some of these songs. I didn’t know him at all. I had no connections to the industry. But I reached out to him through his website and dropped him a note. And he responded. I sent him a song and he really liked it, and it snowballed from there. It went from one track to two, and then the whole album.

Eventually, Nick said he’d love to mix the album. He also asked me what I wanted to do with the album when it was finished. I had no answer for him at that moment. I was investing my own money into the project, but I hadn’t even thought about it being something I would release. I was doing it just for me.

Nick made me realize quickly that this was worthy of being heard. Once he opened that door, I had the confidence to start sending tons of emails a day to anybody I could get to listen to it. I’d write random publications and independent record stores. Everything slowly built up from that tiny seed.

By the time you get to the second Lo-Fi Resistance album, Chalk Lines, from 2012, I started to further build up my reputation. I was able to use the first record as a calling card, and it opened a lot of doors. I got to meet and work with people like Gavin Harrison, Colin Edwin, John Giblin, and John Wesley. The record was more ambitious, and in retrospect, I can see that big leaps were starting to happen.

How were you able to afford such impressive musicians at that time?

Nobody knew me, so there was no buddy deal happening with anyone at that point. Everybody was really good about assessing the situation and realizing I am an independent artist who’s taken this all on by himself. Everybody had their own price, and I paid what they determined to be appropriate. That’s how I wanted it to be done. It was financially difficult and there was no guarantee of any return.

Lo-Fi Resistance slowly built up an audience and Chalk Lines was appreciated within progressive rock circles because of the people who were attached to it. But when I made the third album, The Age of Enlightenment from 2014, I kind of shot myself in the foot. I chose not to lean into the progressive rock direction and build up a trajectory within the genre. I knocked the wall down and made a strange, quasi-electronic, more experimental record. It came and went without anybody really noticing it.

I learned the hard way that I couldn’t just do whatever I wanted and expect everybody was going to show up for it. I had no guests on it at all. I did it all myself, partially out of protest. I didn’t want people tuning into my work just because of the other people that played on it. I wanted to make something that was just me. It was an important record to me, but not a great commercial move.

I could have continued as Lo-Fi Resistance and evolved it into a band, not dissimilarly to how Porcupine Tree started out as a bedroom project. But at that point, I believed I had satisfied the possibilities of that project and that I could release music under my own name again. I felt I had broken the link between my early childhood output and the new identity I had created.

Randy McStine and Steven Wilson perform with Porcupine Tree at The Anthem, Washington, D.C., September 2022 | Photo: Joe Del Tufo

Randy McStine and Steven Wilson perform with Porcupine Tree at The Anthem, Washington, D.C., September 2022 | Photo: Joe Del Tufo

Talk about the journey that led to you joining Porcupine Tree.

This goes back to the second Lo-Fi Resistance record, Chalk Lines. I first met Gavin Harrison in 2011 when he agreed to play on it. He then championed the record over the years and brought it up during interviews and as an example of studio work he was proud of.

In 2019, when I saw The Pineapple Thief was going to be touring North America, I asked him if they had an opening act. He immediately responded and asked if it was something I was interested in. I said yes, and they chose to have me on the tour. Through the process of touring with those guys, I got to know Gavin on a deeper level. He could see and hear me every night in terms of what I was doing and what I was capable of.

At the time, I didn’t know Porcupine Tree was even remotely in the conversation. But then we arrive at September 2021, and I’m out walking my dog. I came home to a couple of missed calls from Gavin, which seemed very random to me. We got on the phone and after a minute of niceties, he told me that Porcupine Tree was coming back with a new album and tour, and asked if I would like to join them as their touring guitarist and backing vocalist. I immediately said yes and scribbled down some vague details about how things would progress.

After getting over the shock of that, there was this period of three or four months during which there was very little communication. And that was laid out to me from the start, but I still had many moments when I thought, “Is this really happening? Am I going to get a call that says they’ve changed their mind and are getting someone else?” I started getting in my own head about it. But at the turn of the year, everything started kicking into gear. That’s when my communication with Steven Wilson started and I was sent the Closure/Continuation record so I could start studying it and figuring out how to approach it in a live context.

So, things became very real as I listened to the new record and realized that they picked me for a reason. They wanted me to really pay attention to the details and hear myself in it, even though I had nothing to do with creating it. I had to imagine that I was already a part of the music.

I also did a ton of research on the back catalog. I’d cross-reference studio and live recordings so I was prepared to approach the setlist. With the new stuff, I had to discover what it was I’d bring to the table. I excavated a lot of detail I don’t think they expected I would go into, like fine details in production—things they were unclear on in terms of getting assigned to guitars or keyboards, but things I knew I could handle for them. So, I took it upon myself to figure out the split of duties between Steven and I when it came to harmony vocals and guitar parts, and what I could do to take as much work off his shoulders as the frontman as possible. I drafted a giant Google doc going through the songs section by section, with my suggestions about who should handle which part. We went with about 95 percent of what I drafted. In some instances, Steven would flip things around.

I wanted to walk into the rehearsal room for the first time as bulletproof as possible. There was a lot of pressure on me, especially given that somebody else used to be in my position and I needed to justify being there. The rehearsals went great. We cut the time down because it all went so smoothly. And then we did the tour, and it was incredible.

The experience was so full circle and surreal. At age 15, I bought In Absentia at Tower Records in New York City, when I was there to play a gig at The Bitter End during my instrumental guitar days. I took it home and it blew me away. I was a fan from that point on. I found as much of their back catalog as possible, as well.

I saw every tour the band did until it went on hiatus. It began at a dingy club in Syracuse, New York on the Deadwing tour, during which they played for maybe 100 people, all the way to the Radio City Music Hall gig on The Incident tour, which was their second-to-last gig before stopping.

So, to find myself onstage about to launch into “Blackest Eyes” for the first time, 12 years since their last show, was an indescribable experience. And then to actually play at Radio City Music Hall with them in 2022 was unbelievable.

Photo: Joe Del Tufo

Photo: Joe Del Tufo

Tell me more about the first gig you played with Porcupine Tree, as well as the last one.

Before the first gig, which was in Toronto, right up until an hour before the show, I was completely comfortable and confident. But as the moment drew near, I started to realize what was about to happen and that there was no safety net. We weren’t in rehearsal anymore. So, it’s time to really do it. I was getting a stressful feeling in my stomach that this is really gonna happen. I started doing a lot of breathing exercises and meditation to calm the nerves and be present. I told myself, “This is exactly why I’m here and this is what I’m gonna do.”

The moment of getting the signal to go on and then crossing the barrier from backstage gave me this feeling of, “You’re one step from the point of no turning back.” But we went out there and there was a standing ovation before we started playing for a couple of minutes, which felt great. And then we launched into the show and away we went.

There were several moments when I felt I was leaving my own body and observing myself on stage performing. I would have to remind myself that I’m actually the one playing and singing with the band to remain focused in the moment. It was very emotionally overwhelming. Once we got that first one under our belts, I felt like I could really start to take ownership of my position on stage. Steven and I also built up a sort of unspoken onstage relationship and we quickly locked into a chemistry that evolved throughout the tour.

It was amazing to form a connection with fans who are singing the words to the songs along with you. They’re anticipating the solo you’re about to play. It was a very powerful thing and my first real taste of what it might be like if I could get my solo career to a point that resembles anything like that.

I felt like I was on stage with a band that had won the right to present itself in a really heightened way. And the more we did it, the more I felt emboldened to perform more and really try to connect not just with the people right in the front, but at the very back of the arenas. It became real rock and roll and was just plain fun. It got me out of my shell a bit. I really had to help put on a show.

In terms of the last show, really, there were two of them. There was the last show in 2022 at the O2 Arena in Wembley. I had the assumption that it was the end of the line and that the journey was over. So, it was very emotional for me. My wife flew out for the gig. I tried to savor every moment. But not too long afterwards, I got word there was going to be another leg in the summer of 2023 in Europe. So, I was able to prolong that feeling of excitement of being in this band.

Now, that second leg became very unique, because after we played our first show, our bassist Nate Navarro had to go home for a family emergency, and he didn’t rejoin the tour. We had two days to figure out what we were going to do. We had his bass tracks recorded from a prior show, and we chose to continue as a quartet. There were 11 gigs and as they went along, we realized the shows went off without a hitch. It worked much better than any of us thought it would, so we decided to continue that way.

After Nate left the tour, there were suddenly just two people in the front line. That meant there was more ground to cover with just Steven and I out there interacting. So, the personal chemistry onstage changed again. The experience was completely different. Steven and I spent more time together as well. We’d hang out, go to record stores, and all that kind of stuff.

By the time we got to the last show in 2023 at Musik im Park in Schwetzingen, Germany, we were a well-oiled machine. We were completely used to playing the show as four people. We had all this offstage banter and in-jokes, and had a deeper connection with one another.

During the encore, when Richard and Steven would go out and do “Collapse the Light into the Earth,” I found myself standing at the side of the stage holding back tears, because I thought, “Okay, maybe this time it is the end for real.” It’s hard to let go of something you’ve worked so hard to develop and care for. To have arrived at that place as a musician doing exactly the kind of gig you always dreamed of meant I had nothing but gratitude, but it also felt bittersweet because the end was in sight.

I tried to play that gig as well as any other, but I was probably a little bit more observant of everything in the moment to give myself a mental snapshot of the experience that I could hold onto.

I’m not making a definitive statement here, but I’m not fully convinced that was truly the end of the band. But I’ve had to train myself to accept that it might have been.

Photo: Hajo Müller

Photo: Hajo Müller

Discuss some of the antics that took place behind the scenes of the Porcupine Tree tours.

As the tours went on, we all had more time to hang out. Steven is such an encyclopedia of music, and we would have lots of conversations about all kinds of artists and albums. There’s a ton of overlap in terms of things I already had exposure to, but also lots I hadn’t. At some point, we landed on the subject of Southern rock and the idea that because I was American meant I must subscribe in some way to Southern rock tropes. We’d joke about that.

At a certain point, a Wikipedia page of one of these classic Southern rock bands came up and we realized it had dozens and dozens of people in and out of it throughout its history, and everyone would have a ridiculous nickname. So, we decided to adopt Southern rock nicknames for everyone in our band.

For some reason, they decided to call me Randy “The Mink” McStine. We tried Steven “Rust Weasel” Wilson at one point, and he eventually became Steven “Slingshot” Wilson. We’ve since come up with entire mythologies about who these characters are. We even have lists of song titles they’ve recorded.

During the soundcheck ahead of the final show in Germany, Steven actually launched into “Sweet Home Alabama,” and we played a couple of verses. So, we have established the precedent of Porcupine Tree playing a really, really poor version of it. [laughs] It cracks me up that potentially the last soundcheck Porcupine Tree might ever do was playing a Lynyrd Skynyrd song.

What was it like for you to have the Closure/Continuation.Live. box set emerge and realize you’re now part of the band’s discography, too?

It’s such an honor to have played a role in the legacy of this band that contributed to my own musical development in a really big way. It’s a great document of where we landed. It’s a moment captured in time, and it was very surreal for me to hold it in my hands and then see it on a screen, realizing I was part of it.

Describe your role on the 2025 Steven Wilson album The Overview and its accompanying tour.

In December 2023, Steven had this Christmas song called “December Skies,” which he unexpectedly produced using AI-generated lyrics. He asked if I could play a guitar solo on it and sing some harmony vocals. So, I did, and it came out really nice. Essentially, it’s just the two of us on this track. Even though I had done a bunch of shows for Porcupine Tree, this was the first time in a studio context I had done tracks for him.

I think Steven realized our vocals blend well together. That led to the next step, in which he had a demo in progress for what is now side two of The Overview. I knew the stakes were higher, because we were discussing something that will become his next solo album.

Steven sent me the music in progress, and at that point, it was him playing all the instruments. He pointed out where guitar solos could go and some vocal lines he thought I could put harmonies on. It was very much in the demo phase, and he told me to do whatever I wanted. So, I got to work, put on my producer and arranger hats, and got into micro-detail on what I thought might sound cool based on the space available to me on the canvas. In addition to guitar and vocals, I’d pick up a bass for a couple of lines here and there, and even contribute a keyboard solo.

I saw it as an opportunity to present a bigger picture version of who I am to Steven. He really only knew me for what I did with Porcupine Tree, previously. Now, we were into the realm of “What is this person going to be able to bring to my music, creatively?” We went back and forth for a couple of months constantly as he was building up the music. I kept adding more and more as he would send new versions. To my delight and surprise, he was taken aback by what I gave him and most of what I provided ended up on the final cut of the record. You’ll hear some significant guitar solos, vocals, and ear candy details from me on it that I’m proud of.

In terms of the upcoming tour, I was surprised to get the call. Historically, Steven has kept Porcupine Tree and his solo career separate, particularly on stage, with little exception. I didn’t assume that’s where things were heading, but thankfully it did. I’m looking forward to playing a part in bringing this material to life on stage. A huge difference this time is that I’ll be playing parts that I actually wrote for the music.

All of the musicians who were in Steven’s band before I joined have had serious chops. This opportunity is a catalyst for me to expand my own vocabulary as a guitarist ahead of the tour. I welcome the challenge, because it can only make me better as a player. It’ll also help continue to move my own music forward.

Marco Minnemann and Randy McStine, 2019 | Photo: Erik Nielsen

Marco Minnemann and Randy McStine, 2019 | Photo: Erik Nielsen

You’re about to release McStine & Minnemann III. Talk about how the duo began and what people can expect from the new record.

It was about taking the seed of an idea and blowing it up into something neither of us anticipated. We met through another project we were attached to and really hit it off. I proposed the idea of doing an EP together in late 2019. And then COVID-19 hit. I suppose you could call it a silver lining of the pandemic, but we found ourselves with bandwidth to work intensely on music together, and the EP turned into a full album, which then immediately turned into a second record.

It was almost a maniacal, childlike process to work together. We loved giving each other these ideas and pushing the boundaries of song structures. It was an exercise in seeing what we could get away with. From my perspective, packing as much as you can into the small package of a short song was really interesting. I hate to use the word “content,” but the fact is we’ve arrived at a point in which people consume information in smaller and smaller amounts of time. So, we tried to cram as much information as possible into these songs.

We didn’t deliberately decide every song had to be under three minutes, but that’s where we ended up. You’ll hear micro-symphonies within the space of five seconds on the records. And by the time you notice it, it’s gone. It’s the opposite of minimalism in a way.

We put together a live band with Mohini Dey and Nick D’Virgilio and did a couple of shows, but Porcupine Tree came along. So, that took the focus off the band and my solo record. But we still decided to do a third McStine & Minnemann album.

We felt it’s important to remember the chemistry we have. The new record is the most focused one we’ve done. It does what a third album should do, which is observe what came before and bridge the gap between the two records. This one also reflects the fact that I’ve grown as a writer and producer since the last record, so I had a fresh perspective on the work and how to finish it.

You contributed to Stu Hamm’s most recent LP Hold Fast and performed as part of a mini-tour in 2024 with him. What was it like to focus on the jazz-rock universe?

I think it relates to my early instrumental work in some ways. It’s about the long road back to that part of my musical identity. When I was a kid in third grade, seeing Stu Hamm with Joe Satriani on the first G3 tour had a major influence on me as a player. And through this strange career I’ve had, I ended up playing with Stu in the Jane Getter Premonition. And that led to Stu calling me to do one of his tours in the summer of 2016. In 2023, he asked me to contribute vocals to a couple of songs on Hold Fast. He went on to do a few gigs to support it in 2024, with Chad Wackerman on drums and Matt Rohde on keyboards.

I thought, “This is going to throw me into the deep end, stylistically.” I didn’t feel the jazz-fusion space was out of my reach, but I don’t live in that world constantly. So, to get back into that headspace meant a lot of woodshedding so I could hang with those guys and avoid the feeling of “imposter syndrome” from creeping up. I mean, Chad has played with Frank Zappa and Allan Holdsworth. Focusing on that will quickly eat away at you if you let it, and start making you think you don’t belong in the same room as him.

I worked really hard so I could be in the same room as Chad. I have so much admiration for him. It was so fantastic to play with him and hear stories from his past. And again, working with people like Chad will likely open the door to collaborations in the future. It’s all about building musical relationships and trust. I suggested to Chad that my solo music is a blank slate and that whenever I determine where I’m going next, there’s a good chance I’ll be in touch.

Randy McStine and Stu Hamm in concert at Yoshi's, Oakland, CA, October 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

Randy McStine and Stu Hamm in concert at Yoshi's, Oakland, CA, October 2024 | Photo: Anil Prasad

You’ve combined musicians in your solo work that have had significant conflicts among themselves. Describe the philosophy that enables you to seamlessly collaborate with them all despite those situations.

I think a lot of it goes back to my childhood growing up in a chaotic household in which interpersonal relationships were not ideal. I had to try to keep the peace. It’s something I developed throughout my life. I also recognized there’s something in me that could hit the tripwire and end up in a negative space. So, I’ve tried to build up layers of failsafe in terms of how I handle being confronted by difficult situations and difficult people.

I will not resort to tendencies that escalate conflict. I go in the opposite direction, which is to take temperatures down and shift the focus onto other things. I try to keep the musical goal in mind for everybody. It’s a guiding light, regardless of who I’m dealing with. We all want the music to be something we’re proud of and content with.

I have no problem inserting myself into the situation in ways that will attempt to defuse the bomb. It could be as simple as saying something. It could be locking eyes with somebody and motioning that we understand one another and that something is about to happen that shouldn’t and should be avoided. I also have a really dark sense of humor that can go a long way as well to calm situations. At the end of the day, the goal is to bypass all the baggage, focus on the job at hand, and make some music.

What keeps you creatively motivated?

It’s about the continued pursuit of self-expression and wanting to grow as a person and an artist. Every time I commit to doing a session, record, or tour, it’s a decision to push myself to be something I didn’t know I could be until I do that thing.

I’m always resisting the feeling of being complacent and stuck in a comfort zone in which I can coast. I get uncomfortable with being too comfortable. Whenever that happens, I try to run as fast as I can towards another direction I’ve never gone before. Or I’ll try to bring a lot of different directions together in a new way for me.

I’m ultimately driven by the desire to create new things and observe if I’ve made progress. Sharing music with the world is the final step of acceptance. When I let go of it and am unafraid of how it will be perceived, it becomes more of a celebration and motivation to start another chapter.

I’m always looking forward to the next song, the next record, and the next tour. There’s always something that has yet to reveal itself until the moment the music is happening. It keeps life beautiful and interesting.