Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Robby Aceto

Universe of Possibility

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2024 Anil Prasad.

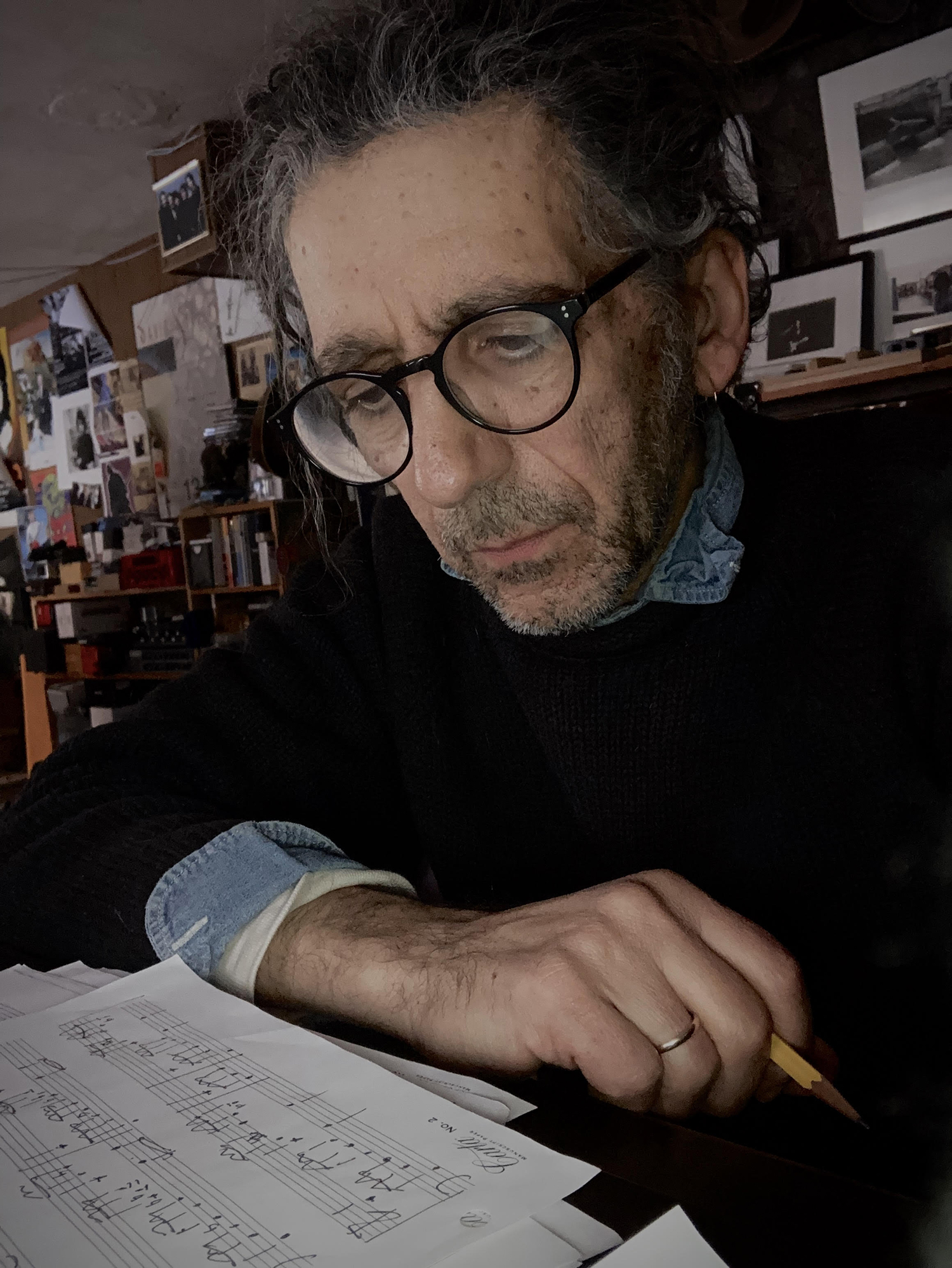

Photo: Rebecca Proctor

Photo: Rebecca Proctor

In 2024, Robby Aceto is driven to write, record, and perform music solely to satisfy his inner voice. Prior to his decision to exclusively follow his muse, the guitarist, pianist, singer-songwriter, and composer had engaged with the larger music industry at significant levels.

He’s worked with Jerry Harrison, The Heads, Jansen Barbieri Karn, David Sylvian, David Torn, and Tom Tom Club as a sideman and collaborator. He’s played major roles with several of them in realizing their music at multiple levels, from performances to recordings to technical and production oversight. He has also found himself serving as an advisor, counselor, and sounding board to several of them.

The key reason all of them engaged Aceto is simple: trust. They understood the realization of the art of sound is always top of mind for him. He has no use for business acrobatics, ego-driven battles, or making music according to someone else’s template. And he’s encouraged the artists he’s worked with to adopt similar mindsets. Sometimes they’ve listened. And sometimes he’s found himself removed from the inner circle because of his candor. The reality is that’s sometimes the price of integrity.

In his solo and collaborative band work, Aceto has put those principles at the forefront of his intent and interaction. In 1996, he released his first solo album Code. It combines experimental guitar, ambient songcraft, creative looping, and dynamic rhythms into a cohesive and engaging whole. Aceto infused the proceedings with imaginative performances by Steve Jansen, Bill King, Happy Rhodes, David Torn, Doug Wyatt, and Gota Yashiki.

Following Code, the subsequent 28 years have seen Aceto evolve far beyond his status as a gun for hire.

He co-founded the improvisatory trio Cloud Chamber Orchestra in 2008, which creates live soundtracks for silent film to this day.

He also launched a successful film composing career that’s seen him contribute scores to critically-acclaimed independent features, including Change in the Family, Freak the Language, The God Squad, Hidden Books, Jungle Warfare College, Patient 001, 12 Ingredients Over the Generations, and Walking the Line.

Another core focus for Aceto is Birds Through Fire, a trio that explores the intersections between electronica, chamber music, soundscapes, and rock. The band also features Paul Smyth on keyboards and electronic treatments, and Paul Cartwright on bass, keyboards, guitar, vocals, and percussion. It has released two albums to date: 2015’s Letters to Thurza and 2023’s The Sting of Everything.

“Robby’s depth as a composer, orchestrator, and musician is of the highest order,” said Cartwright. “He comes at music from so many points of entry. Whether it’s experimental and textural guitar, orchestral string arranging, or as a lyricist, he seems to be able to do it all with amazing honesty, enthusiasm, and emotion. Robby is able to take a song’s seed and deconstruct and reconstruct it to make music that sounds like all three of us. He’s always very curious about where the song idea comes from, yet isn’t afraid to make it his own. I’ve never worked with such a fully-formed musician that can span musical distances with such ease.”

Even though Aceto generally concentrates on his own projects these days, there are two significant exceptions. The first is Douglas September, the revered singer-songwriter known for highly-literate and poetic observational works set in an eclectic mix of rock, pop, folk, and atmospheric contexts. Aceto has worked with September since 1998 and remains close friends with him. He’s contributed to the majority of September’s releases, including the forthcoming 2025 recording Rare Breeds.

“Robby’s skill, dedication, musical intelligence, and humility, not to mention his bad-ass guitar playing, are only a few of the reasons he gives me hope for lasting integrity in any kind of meaningful creativity,” said September. “If there’s anyone on this great Earth that knows me better than myself, when it comes to what the heck I do, it’s Robby. I can unequivocally say that without Robby, my creative output would have been completely unfulfilling and my musical explorations without reward.”

Aceto also plays a major role in the career of his son Alexei Aceto. Alexei is a highly-regarded, emerging classical pianist that’s been working as a professional musician since 2017. He regularly performs solo and with orchestras, and has been featured across classical media. Robby has written solo piano and chamber music pieces for Alexei, and now considers classical composition an area of significant interest.

Photo: Rebecca Proctor

Photo: Rebecca Proctor

Explore the musical life you’ve been leading since you shifted your focus away from touring to recording and composition.

Things really began to change for me when my son Alexei was born in 1999, right at the peak of my touring days. I had been quite busy through the 1990s and after with several different projects, but by 2006, he was in school, so it became a bit more complicated to get out the door. Every time I’d tour with somebody, I’d have to get a nanny and go through a training ritual. My wife also travels for work, so touring for me really became a mixed bag. It was fun, it was my work, but it was also getting more difficult to sustain.

Sometimes the logistics would work out, but sometimes not. I liked traveling and playing gigs in different parts of the world, but by 2006, I felt I had really done it enough and wanted to be more involved in my boy’s life. So, I had to figure out how to reconfigure my career in a way that would better accommodate family life. I don’t think this is a story unique to me. Everyone who has a career and a family has to find their own solution.

I had to start saying no to things, especially longer outings with Tom Tom Club. They would go out and do a string of dates, but it would eat up a huge amount of time. Even if it was only a handful of dates, they would want to rehearse for a week or two prior. That was totally commendable from a professional perspective, and helped foster the group feeling. But my thought was, “No, we don’t have to rehearse for two weeks. It’s music you’ve been playing for decades.” So, that time commitment became less tenable and eventually I had to leave the group. I’m happy to say we had an amicable parting. I consider Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth great friends. They were wonderful to our toddler, always sending me home with something for him. We always said Tina was like his “Rock and Roll fairy godmother.”

As early as 1999, I was already exploring other possibilities and ways forward. By 2001, I had the chance to collaborate with Bobby Lurie on his score for the film The God Squad. I remember feeling, “This is a mode of work I could really feel connected to.” He entrusted me with mixing the project and helped me build up a nice little music production room, so I began working my way into doing soundtracks.

In the beginning, I did a lot of work for next to nothing just to get experience, and in the process started to build up some working relationships. I was still going on the road, but the idea of working from home just became so attractive. I got to work with some great up-and-coming indie filmmakers, and have gone on to do multiple pictures with several of them.

Doing film scores and making a real study of the process became my focus. From a career standpoint, it was a natural progression. I’m comfortable working alone, and my compositional style seems to lend itself to what one might consider a visual approach.

I’ve also continued to perform since 2008 with an improvising trio called Cloud Chamber Orchestra, doing live scores for silent film. We play every year at the Finger Lakes Environmental Film Festival (FLEFF) in Ithaca, New York. Working with a cutting-edge festival like FLEFF presents a great creative opportunity. In our case, it provides access to performing to these monumental classics of film history. This past year, we performed a score for Mother, the second film in the Bolshevik trilogy by Vsevolod Pudovkin from 1926. We had already done Storm Over Asia a few years back, so now we only need to perform with The Last of St. Petersburg to complete the trilogy.

But the most important facet of my musical life of the last 20 years or so, without a doubt, has been focusing on Alexei, who emerged at a fairly young age as a virtuosic talent. He’s 25 now and has been living in Indiana the last two years attending Jacobs School of Music working on his Masters degree in piano performance. He completed that degree last May. As a kid, and as his talent became more obvious and he really started to develop, it was clear I had to put my energy behind supporting him every way I could. He’s really quite incredible and I feel like it’s been the privilege of my life to observe his gift unfold.

I’ve been playing music all my life, and I think I’ve been disciplined in developing my abilities, but he chose to play classical music. You have to train for 20 years before you can even think about approaching performance of this kind of music with any level of sufficient understanding. The sheer physicality of it, the necessity of muscle training, and developing the many levels of sensitivity you need are all significant elements. You’re dealing with a mechanism, the point of contact with the key, and producing your tone through that. It’s unlike a stringed instrument in which you have direct physical contact with the string. You can develop that sensation of string contact much more quickly that way. Plus, I’m entirely self-taught, so in that way it’s like your idiosyncrasies become your technique.

With piano, you need a mentor—someone who has a fully-formed technique and knowledge of the literature. We were lucky in that since a young age, Alexei has been in the hands of an incredible concert pianist and teacher of deeply profound understanding by the name of Charis Dimaras. They forged an incredible relationship in the years Alexei studied with him and they remain very close. Charis has really been like a second father.

From the time he was very young, Alexei had his piano room directly above my home studio. Throughout high school and later, during his undergrad degree when he’d come home to visit, I’d hear him up there working. The music he was acquiring became increasingly complex and virtuosic in nature. COVID-19 hit during his junior year of college, so he basically attended the second half of that year studying remotely from home. He was up there playing every day. Colleagues would come over and they’d be rehearsing chamber music. Even as students, it involved playing at a fairly high level. And hearing him working on this intensely virtuosic music day in, day out, I know had the effect of rewiring my brain.

Oddly enough, the piano is the only instrument I had any training on, so I’ve always felt a connection to the instrument. It’s actually informed my life as a guitarist and I’ve worked at employing those subtleties of voicing and shading—subtleties that are central for a pianist but easily overlooked if you play an amplified instrument. It’s easy to be seduced by all the power and energy the electric guitar affords you. You develop a relationship with your instrument and an amp, and once you have a sound you’re comfortable with, you lean on that and trust in it, but you can become complacent.

An identity as a guitar player, whatever that is, began to feel somewhat constrictive. Around that time, 2006 or so, I was also thinking about mortality. I wanted to make a body of work I could leave behind for Alexei. I don’t mean music performed and embedded on a plastic disc or digital file for him to passively listen to, but real, living music on paper for him to interpret for himself. This has now been a process over many years. Back when he graduated high school, I presented him with a book of solo piano music I had written for him—about 50 pages of score. It was my graduation present to him and my first project of that type. I realized at that point, this is really what I’m becoming about.

So, my work is now an amalgam of what I’ve always been doing: film scores, collaborating on album projects, co-writing, and producing. But I’m also now becoming about working on scores and writing solo piano music and chamber pieces for Alexei.

I walked away from the whole road dog element. I don’t miss it. It helps that Alexei keeps asking me “What about writing a sonata, or something large for piano and amplified guitar?” Well, you need quiet and focus, and to sit in one place for a while to do something like that.

Out of necessity, I’ve been learning to communicate ideas of sound in notation, on paper. Last winter, I finished working on a set of four pieces for piano quartet. You begin to make this transition from a focus on the instant production of sound and musical ideas to placing black marks on paper in such a way that describes the effect. It becomes, in a way, a visual medium.

In general, the piano also became the source for a lot of continued ear development that I translate into the guitar. There are very esoteric practices which are second nature to pianists and inform the way you need to practice, because of the way the architecture and physicality of the instrument works. As a result of sitting at the piano more, I’ve discovered voicing effects that on the guitar are easy to miss if you’re not focused on them. It has been very rewarding adapting them to the guitar. Working on more kinds of music, and thinking of my musical life in much broader terms has really opened up new areas of interest and exploration for me.

Robby Aceto and Alexei Aceto | Photo: Rebecca Proctor

Robby Aceto and Alexei Aceto | Photo: Rebecca Proctor

You’ve described Birds Through Fire as an art collective. Tell me about your involvement in the trio.

It’s such an unusual project and has been central to my output for the last decade and a half. It’s a perfect study in long-distance collaboration, something that has now become more normal during and after the pandemic. But in 2010, it was an unusual way to go about making music.

My involvement with them began around the time the news broke that Mick Karn was seriously ill. Two musicians in Australia, Paul Cartwright and Paul Smyth who are both huge fans of Mick, felt compelled to do a tribute track for him. They were looking for a collaborator to work on it with them who had a personal connection with Mick. They had been in touch with Debi Zornes at Medium Productions, who sent them to David Torn, who suggested they get in touch with me.

They sent me a very lively track. It was three main parts over a drum loop with all kinds of intense, generative sound floating around in it. Paul Cartwright, the bass player, was doing something very evocative of Mick. It was kind of chilling for me because it sounded so much like him. When they sent me the track, I was on my way to support Mick in Cyprus that summer when he was getting chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

After I got home from Cyprus, I started writing and working on the musical structure of the piece. Collaborating long-distance can be fairly challenging, and when you add crossing the date line and swapping Northern and Southern hemispheres to it, it really gets interesting. We called it topsy-turvy. It's morning here, it’s night there. It’s winter here, it’s summer there. So things, especially creative projects, just really take on another level of complexity.

They gave me complete license on the track. I did a lot of cutting, providing more of a shape, and doing a lot of overdubbing creating a drum and bass mashup with some crazy dissonant guitar improvisations. But as it became more structured, it also became obvious it wanted to be a song.

Mick passed away that winter, and I was in grief. At that point I wrote the lyrics. The resulting track, “A Portrait in Amber,” became a story of friendship and about notions of the irreconcilability of ephemera and permanence through the image of an insect fossilized in tree resin. I finished it and sent it off to them, thinking it would be a one off. They came back and said, “Would you like to do the whole album with us?” I didn’t have another band project at the time, and they were lovely guys. They had interesting music and propounded this notion of a true collective. I felt the track had come out quite good, and it seemed like a good collaboration so I threw myself into it.

They were very unorthodox in their compositional approach, using synths, wonky upright piano, and sometimes even things like an iPhone to make sounds, and incorporating field recordings and aleatoric elements. In a way, it was very musique concrète. They were involved with and in love with electronica, generative synthesis, sound effects, and all kinds of ambient noise. It presented a fertile playground.

They sent me stems of the music they had been working on together. It was this enormous trove of creative output that was unconnected and sprawling. Little by little, I’d isolate parts and say, “Well, there might be a song in here.” I sort of saw my role as helping to shape their music into something that resembled a song format, but without the format. They also wanted a singer. I hadn’t done much singing since completing my 1996 solo album Code, so the collaboration also provided me a kind of outlet for that as well.

For me, that entire first album, Letters to Thurza, reflected my relationship with Mick. I sort of exorcized through the music what I was feeling about that incredibly painful and tragic loss. Most of the writing I contributed was either directly, or at least obliquely about him. I wrote some string arrangements. There was a spoken-word piece, and some steady-state kind of writing. It took us a little more than four years to finish it. I took the tracks down to David Torn and he mastered them at his place in Bearsville. We finally got it released in 2015.

Fast forward a few years. About a year before COVID-19 clobbered everyone, Paul Cartwright and Paul Smyth surfaced again and wanted to do a second album. We knocked ideas around for a while and had just begun serious work on it when the pandemic hit. It threw any sense of day-to-day life into chaos, and pressing forward became really difficult. Just surviving was very much in the front of everyone’s mind.

As a result, the nature of our second record, The Sting of Everything from 2023, is quite a bit different. It was less spontaneous and improvisatory, and focused a lot more on structure. Also, the deadly impact of the virus had a huge effect on the ideas in the writing. In many respects, it was very much a response to the epic calamity that was COVID-19. The album has a focus on family and looking for community, which it seemed like human society was rapidly losing. So, it’s vastly different, but also has some interesting and compelling similarities. And like Letters to Thurza, it’s very immersive and emotionally complex.

It was completely organic in the way it came out. The two Pauls had been working together remotely in Australia–one in Sydney, the other in Melbourne, which is in itself a great physical distance, and they rarely saw each other. Paul Smyth and his whole family got COVID-19 and were quite ill, and he completely disappeared from the equation. So, Paul Cartwright and I carried on and over the course of the next few years managed to complete what became disc one of what emerged as a two-disc album. At the end of the process, I was doing final mixes and suddenly Paul Smyth surfaced, with this massive explosion of incredible creative energy.

For all intents and purposes the record was finished at that point, but it seemed so stupid that because Paul Smyth had been sidelined by COVID-19 that he hadn’t been able to participate. So, we decided that with a bit more work we could release a double album—one disc with the songs Paul Cartwright and I had completed, and a second ambient, generative disc that Paul Smyth could produce, but that the rest of us would collaborate on as well.

I took on one of the pieces and did some cutting and restructuring, and so was able to make contributions to that set of music. Paul Cartwright also did some playing on it. In those ways, disc two was still a group project.

Going back to disc one—the song disc—I once again saw my role as an editorial one, providing structures and shapes within a song format that Paul Cartwright had initially sketched out. The disc also includes a song that wasn’t originally intended to be on the album. Paul Cartwright had written “The World Inside Your Room” for his daughter Eve. Several years had gone by since Letters to Thurza had been released and we weren’t working together in the interim. He presented the song and said he was uncomfortable singing it because it was so personal, and asked if I would sing it and write a string arrangement for it. So, I was happy to contribute, thinking it was going to be a private, personal piece. But he was very happy with how it came out and that’s when he decided he wanted to do another project together, and that he wanted it to be on the album.

Shortly after the release of The Sting of Everything, Paul Cartwright brought about another collaboration with Australian music legend Brian Cadd. This was possibly in response to the many global conflagrations we had been witnessing. Paul Cartwright had written a spoken-word piece titled “Bullet Wind.” Brian was approached with the idea of doing a spoken word track with Birds Through Fire, which I think was out of the ordinary for him, and he performed this incredible dramatic recitation for us. It was absolutely chilling. We built the track around him and released it as a digital one-off.

Paul Cartwright has on his own very-recently completed spoken word piece with Australian actress Jane Clifton. So he’s carrying on with this Birds Through Fire tradition of music pieces with spoken word that began on Letters To Thurza with “Poeme,” our first track of this kind. We did that piece with the fantastically talented Barcelona-based singer, Maïa Vidal.

Expand on working with Bobby Lurie to make The God Squad score and its accompanying soundtrack album.

First, I should say that if people ever get the opportunity to see this chilling environmental documentary by Emily Hart, they really should. Anyone with a feeling for or respect for nature, and a general mistrust of the inner workings of Congress and the influence of corporate lobbyists in our government, would find it of great interest. I still feel very strongly about that music, especially since it was my first serious collaboration on a film.

I met Bobby Lurie for the first time after a gig I played in New York City with Tom Tom Club in 2000. He was friends with Doug McKean, who was the engineer at that time working on their recordings. But it turned out we had another friend in common in Karl Derfler, who is a well known and incredibly accomplished recording engineer and mixer in the Bay Area. Karl had been the engineer and mixer on the recordings of the Billy Nayer Show, this wild, offbeat and intensely creative music group Bobby had for years with Corey McAbee.

Bobby is a great musician and was collaborating with Emily on this documentary film about the U.S. Endangered Species Committee who had made a controversial decision in 1992 allowing federal timber sales in protected Northern Spotted Owl habitat. That committee basically had the power of life and death over this vanishing species of owl, and people on Capitol hill just referred to them as The God Squad for that reason.

Bobby had something specific in mind for his score and approached me about collaborating. He sent me the cues, which were just single melody lines written out, with no performance indications, timings, or even suggestion of instruments. He wanted to just see how I might approach these fresh, skeletal ideas. I was really intrigued and we met in New York and set up in an old theater in Alphabet City in Manhattan, which had just been bought by Lenny Kravitz.

Doug came and set up a mobile recording environment. The place was under construction. There was no heat except from a jobsite heater. It was freezing cold. We would play until it got too cold, then fire up the salamander until it got warm enough to continue. We recorded about four hours of improvisation based on these few pages of melodies that Bobby had written, with Doug McKean engineering. A few weeks later we went to House of Beauty, Doug’s tiny studio in NYC, and did some minimal overdubs. It was all very loose and I was impressed with how calm and collected Bobby was throughout, just letting musical things happen and allowing the score to take its own shape.

He went and made the film mixes, finished his project with Emily, and then went out on tour with Billy Nayer Show. When the film came out, he wanted to release a soundtrack, but because he was still on the road he asked me to do the CD mix. It’s the first record I mixed and arranged completely on my own, which was a real turning point for me. He sent me the drives, which had literally hours of improvisation for me to sort through and shape into an album.

I really owe so much to him, just placing his trust in me in that way. When I was finished mixing, we met up at David Torn’s place in Bearsville and David mastered the project. It really felt like the start of something and I loved our chemistry. Later, I mixed a couple of tracks on one of the Billy Nayer records, but we have yet to do another full scale project together.

Cloud Chamber Orchestra: Chris White, Peter Dodge, and Robby Aceto | Photo: Chris Woolf

Cloud Chamber Orchestra: Chris White, Peter Dodge, and Robby Aceto | Photo: Chris Woolf

Cloud Chamber Orchestra is one of your core vehicles for creating scores, with a focus on silent film. Discuss your interest in that realm.

I began working with silent film because of an incredible film scholar who I’m so fortunate to have known, Dr. Patricia Zimmerman. We worked on many projects over the years and she is someone I became very good friends with. She was a profound intellectual that authored many books on far-ranging subject matter, not only about film and the early era of film, but also urgent topics such as women’s rights, feminism in the arts, war, racism, and social change. She passed away in August 2023, suddenly and tragically, which is just an immeasurable loss.

In a very real way, she formed Cloud Chamber Orchestra. She was a professor of screen studies and the co-director of FLEFF. In 2008, she got in touch with me and said, “I want you to work on a silent film with these two musicians” and she put me together with Peter Dodge, a fabulous trumpet player and pianist, and Chris White, a superb cellist.

The first film we performed together was a 1922 documentary by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest Shoedsack called Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life. It’s about a tribe of nomadic people called the Baktiari who lived in an area that’s now known as Iran but was then called Persia. It didn’t really have a national identity at the time. The filmmakers teamed up with a journalist named Margueritte Harrison who it was rumored was a spy, and they spent the seasonal migration with the nomads.

The film explored the experiences of the Baktiari as they walked literally barefoot over the Zardeh Kuh across the Atlas Mountains. They have done this every year since before who knows when, to bring their flocks to new grasslands on the other side of the range. Watching Grass is like looking through a time bubble at the way people lived in biblical times. It was the first time any Westerners had done the trek across those mountains. It’s a truly mind-blowing documentary. Cloud Chamber Orchestra released a CD of that live recording, which was our first ever performance.

Since then, we’ve done at least one screening every year at FLEFF, and for several years running, Dr. Zimmerman also had us in to perform with the Robert Weine film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari for her history of film aesthetics course. We’ve done probably 15 performances with Caligari, a film that never ceases to amaze.

I think what the trio does is very special and respectful. A lot of people that do scores for silent films seem to come at it from a sort of hipster perspective. Some of them think “We’re a lot smarter and hipper, and more clever than these people were in 1920 that made these films. Look at that goofy makeup and the way they act and glare at the camera.” It’s easy to be cynical and allow yourself to feel superior when the actors are wearing five layers of greasepaint and acting stiff and jerky. Sometimes the camera never moves and you need intertitles to follow the action.

But if you start to look a little deeper at the films of this era, and what the filmmakers were all doing, you realize the level of sincerity and commitment. During the 1920s, it was an entirely new form of art and they were inventing it as they went along. Everyone was deadly serious about making these productions, especially those directors doing narrative storytelling and drama. And then, going back to Grass for a second, just imagine the commitment needed to drag a 50-pound hand-cranked movie camera over a mountain range, on foot, in winter. There was also the matter of keeping the film stock safe from the elements. Some of the tribespeople actually perished during the trek. So, with those realities in mind, we couldn’t approach these films from the silent era with anything other than a similar level of sincerity and respect.

Also, we improvise during our performances. Most groups I know of who do this sort of thing perform through-composed scores. Our process is about mapping out areas in which we can improvise and allow for surprise, and yet still create a cohesive structure for the film. It’s very challenging because I tend to use different instrumentation for every film. Sometimes, I just go out with an electric guitar and time-based effects. Other times, I’ll bring in several instruments, or instruments I’ve made, sometimes even a laptop, looking for the right range of colors. As much planning as we put into it, we’re still largely thinking on our feet during these settings.

Robby Aceto, 1996 | Photo: Randi Anglin

Robby Aceto, 1996 | Photo: Randi Anglin

How do you look back at Code?

Musically, there are a few things I would do differently today, but in terms of when it was made and where I was at, I’m at least not embarrassed by it. I have a lot of gratitude to Jon Durant, who started Alchemy Records, for giving me the platform. I think I might have been one of his first signings. The opportunity came at a really good time for me.

To get a chance to work with David Torn on this music was absolutely fabulous. He’s someone I’ve known for most of my life. He has a most energetic musical imagination, and our process together was natural and very exploratory. Also, he put up with a lot of my insecurities. If I was getting dramatic about something, he would just tell me to figure it out and simply leave the room for a while. This is an incredibly intuitive producer at work. He had much more experience in the studio than I had, but instead of getting authoritative, he just helped me arrive at my own solutions.

I sketched out the material using an 8-bit sampler, so there wasn’t a lot done in the way of pre-production. We dumped those sequences to tape and just started fleshing things out. It’s all extremely personal in terms of the subject matter. The lyrics are metaphorical, like poetry as a form of semiotics. They’re combined in such a way they could mean different things to a listener.

Alchemy was intended to be an instrumentalist’s label, but I’m also a songwriter, so I think Jon may have been perplexed at first with what I had in mind. But to his credit, he allowed me pretty much free rein. Of course, I wanted to showcase the guitar. So, unless it’s a piano or drums, vocals or some other element, much of the sound on that record was in some way derived from guitar.

I went down to David’s place in Bearsville once I had the music structured, but was still working on the poetry elements. We did some basic tracks at Applehead Studios. The music evolved during the recording process in places and as a result, morphed into something unanticipated.

I was still recording vocals right up to the very end of the project, which lasted from mid-December 1995 through the end of January 1996. I had a grid on the wall of the cabin I was living in with the names of the songs, and what state each of them was in, including the notation and lyrics. Every time I took one of the songs off the grid, that meant it was finished. Eventually there was only one song taped to the wall, and when that one got done, suddenly it was over.

Working with David was such an amazing experience. It was just the two of us. He was very patient with me, and we had a lot of laughs. It was also during one of the worst winters we’d experienced in upstate New York in a decade, so we were also struggling with that. The week we started working, we got eight feet of snow. We had to shovel the snow off the roof of the studio so the ceiling wouldn’t collapse.

When we did Code, I was really interested in having the guitar front and center, buoyed by these other ideas, including ambient effects and designing a soundscape for the guitar to inhabit. So, compared to the music I’m doing now, it’s much more of a guitar record. I’ve sort of stopped thinking of myself as a guitarist and more as somebody who writes music and uses the guitar as much as possible.

My one disappointment is that I wasn’t able to go out and tour the album. We had a plan to tour Code with the possibility of involving Mick Karn, Steve Jansen, and Richard Barbieri as the group. But in the end, it just wasn’t feasible.

What can listeners expect from your forthcoming solo album The End of Violence?

These are tracks I started on that coincided with the time of me deciding I’m going to be a musician from home, and that my output was going to be focused on recordings, with infrequent live performances.

Once I built my production room, I started accumulating tracks. The earlier work I’m considering for inclusion is very much in a progression from the kind of music I was doing when I made Code. It’s very guitar-driven, with a lot of fuzz, and angular playing. That’s one half of the approach. The other half is more internalized, and similar in a way to chamber music.

Some of the material is inspired by monumental global events that have occurred, including Hurricane Katrina and the Gulf Wars, and more recently, the pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But is also informed by past events. The arc of history has always been bloody. If you happen to live in a war zone or the path of a hurricane, your experience is singular. American culture is very self-absorbed, very myopic, but not far away they are still lobbing missiles into Ukraine every day and a lot of innocent people are getting killed for no reason. But even if you are someone who only witnesses these events through the eye of a news camera, they are still life-altering and you need to live responsibly, with an awareness of the intensity of calamity being visited on people pretty much everywhere else in the world.

I have 10 tracks in progress and I’m in almost an editorial process at this point. I’m hoping to release it within the next year or so.

Let’s go back to the mid-’80s and your group Red Letter. Talk about what that band was about and your ambitions for it.

That was the one group I really made an effort to go all the way with in terms of trying to break and get a deal. It lasted until around 1994. We looked for management. We played showcases. We played a gig at CBGB’s on a bill with another band no-one had heard of at the time. That band was called Live. I remember really liking their guitar player. They went on to get a deal and have had very considerable success. Red Letter was not so lucky, but that’s just how it went.

The style of music we played during the ‘80s and early ‘90s wasn’t exactly in vogue. What was called “progressive rock” was dead. The music scene was cycling through grunge and the post-rock movements.

Red Letter was fairly unique in that everyone in the group was in their way a virtuoso talent, and at a time when musical virtuosity was not really of interest. We weren’t personality-driven with an impressive frontman. We never figured out how to write simple songs. I was really into ambient looping, which no-one was doing, certainly not in a band or song context. We also got into using sequencing, which was a fairly new thing at the time. Our drummer Bill King used a combination of sampling and live drums. Our violinist Frank Martinez used a lot of distortion and ambient looping. He retired from playing, but he’s still to this day one of the best musicians I’ve ever played with.

We were happening right at the beginning of a lot of new music technologies. We had to figure out our own way to make it all work because there was no model for what we were doing. We rehearsed a lot, which had its own rewards. There was a lot of trial and error involved, and a lot of experimentation.

We must have been crazy. It was always a big production to do a gig, and we hauled around about a ton of equipment. But we were doing our own thing. It was a lot of fun and when it all worked it was really exciting. We had the feeling of being a part of something.

At most places we played, like clubs in the Northeast and up and down the Eastern Seaboard, we’d see other bands on stage with just an amp and a stomp box or two. But we’d show up with racks of gear which was very unfashionable, not to mention unwieldy. Because of that we were usually treated in a pretty dismissive way. With help from Karl Derfler, we did a showcase at Montana Studios in New York and a very well-known music industry executive who attended said, “What’s with all the Keith Moon hippie bullshit with this band?” "Hippie bullshit" became our catchphrase to describe all the things we thought relevant and important, and which the music industry did not care about in the least. And then five years later, the jam band scene came along, and "hippie bullshit" and wild improvisatory-style drumming were all of a sudden back in vogue.

Red Letter may have existed at the wrong time, but we made a good effort, and I think made some great music. It just became too much to maintain and the band died by the proverbial thousand cuts just short of a decade together. It was heartbreaking when it ended, but at least we made some interesting music and actually released two albums. We made at least two more albums worth of studio recordings that were never released.

The band fell apart, and I started doing solo gigs featuring ambient guitar improvisations, and some song-oriented things. That brought me to the attention of Jon Durant, which is how Code came about. In the early stages of tracking Code, David Torn let me bring in the core of Red Letter, and they played on several tracks. We had already broken up, but everyone was really committed, and did some great work. It was a very humbling experience to have them involved.

Tom Tom Club, 2000: Victoria Clamp, Robby Aceto, Abdou M'Boup, Chris Frantz, Tina Weymouth, Mystic Bowie, and Bruce Martin | Photo: Brian Ashley White

Tom Tom Club, 2000: Victoria Clamp, Robby Aceto, Abdou M'Boup, Chris Frantz, Tina Weymouth, Mystic Bowie, and Bruce Martin | Photo: Brian Ashley White

How did the opportunity with Tom Tom Club emerge and what was that experience like?

It was a really interesting time. This was around ‘97-’98. Karl Derfler, who I mentioned earlier, was the first person in my early days who expressed any kind of faith that I was a musician worth promoting. He was based in the San Francisco Bay Area and would put me on sessions in San Francisco and Los Angeles. Those were really my first serious professional engagements.

He worked on many projects with Jerry Harrison and got me hired on a record in ‘97 that Jerry was producing for an Irish singer named Noella Hutton. She was like a young Marianne Faithful, in that she was a great blues singer, with a punk edge. Noella was really astonishing and had some great songs. Prairie Prince was the drummer on those sessions and we got to be good friends. Joe Gore came in as well and did some crazy guitar work and it was a blast to watch him work.

I felt like Jerry and I hit it off pretty well, and later that year, he got in touch with me to let me know he was coming to the East Coast to visit Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth. He said they were all going to jam and that I should join them. I said, “I would like nothing better.” So, I went down to Connecticut around Easter time. I brought the same gear I always used, not really knowing what to expect. But it turned out they weren’t jamming. They were recording the second album by The Heads, the post-Talking Heads group the three of them had.

The first Heads album had Debbie Harry, Michael Hutchence, and Johnette Napolitano singing, and an excellent guitarist named Blast. The new album they were doing was going to feature the singer Jimmy Helms, who was from Londonbeat. Chris, Tina, and Jerry said I should just try to work my way into the music they were already doing.

It was a really noisy, energetic, and effective process, sort of like the things they had done with Adrian Belew. Jerry kept saying he wanted it “illbient,” which was the new thing going on then—a sort of drum and bass thing with this weird, textural stuff. It was really exciting and had the hallmarks of what we always think of with Talking Heads and how groundbreaking they were.

They ended up doing most of the record with Jimmy. But during the process of creating it, they got in a legal wrangle with David Byrne over the use of the name. Chris and Tina said it just wasn’t worth it to go into that whole world of a massive legal squabble. So, they put the album aside and said, “Let’s reactivate Tom Tom Club, this group we have full control of.” They asked me if I wanted to do it. I had been a fan of the band, especially Adrian’s manic guitar playing. So, that’s how it happened.

Mariah Carey had recently sampled “Genius of Love” for what became her hit song, “Fantasy.” It was a big success for Chris and Tina and made a lot of things possible. They completed work on their album The Good, The Bad, and the Funky and decided to do a tour to support the release. They were such fun people to be around, and their dynamic as a duo is really interesting. The two of them are incredibly charming in terms of their vibe together and Chris is like a walking encyclopedia of R&B. I also got to know and work with the legendary front-of-house engineer Frank Gallagher, who is one of my favorite people of all time.

Tina has this catchphrase she was constantly using called “The two phases of musicianship.” She said, “There’s the mad genius phase, when you’re writing or working in the studio, and there’s the performing monkey phase when you go out on tour.” [laughs] I thought that was really funny and apt. But I never saw things that way, because I try to see performance as a creative act as well. Still, I tried to embrace my performer monkey for them as best I could.

My feeling about the Tom Tom Club shows is that Chris and Tina weren’t completely embracing their own personhood. They wanted to find and expand into a new audience. It was happening during the emergence of the jam band scene and they made every effort to become a part of that scene. I was thinking, “These bands are still in their diapers, compared to the two of you, who have made some of the most groundbreaking music ever.” So, trying to curry favor with that coterie was puzzling to me.

The shows were very nostalgia-based. I wanted them to be more exploratory and keep moving forward, but I think they were trying to focus on achieving more commercial success.

I made several recordings with them, including The Good, The Bad, and The Funky. I did a lot of overdubs on that. It was very much a Pro Tools event. I also was involved in the re-recording of “Genius of Love.” The original master tapes were lost, and everyone was starting to sample it. So, Chris and Tina decided to re-cut the masters from the ground up, exactly as they were first done. I had to be Ernest Ranglin one day and Adrian Belew another. That was fun for me in a superficial way, but it was also difficult as I was someone trying to forge their own identity. I had to duplicate their parts. Today, if you hear a new sample of “Genius of Love” that came off a multi-track, you may be hearing me. It feels very weird.

We also recorded a live-in-the-studio album called Live from the Clubhouse. That was recorded during a house party at their place on Cock Island in Connecticut. The band Phish were also quite huge at the time and someone organized a CD project with different artists covering their songs called Sharin’ In the Groove. Tom Tom Club did the song “Sand,” which I played on and I think is a fabulously creative re-think of that track.

I left in 2006, but I did return to play a few shows in 2009. They had an offer to do the Island 50 Festival in London, which celebrated 50 years of Chris Blackwell’s label that had been home to Tom Tom Club and a host of other great bands. We did that gig, and the Benicassim Festival in the south of Spain. Those shows were filmed for MTV Germany. Also, there were a couple of dates in Belgium that year. That was the last time I worked with them. So, somewhere out there, there’s quite a bit of documentation from my time with the band.

How did you initially engage with David Sylvian, resulting in you joining him for the 1988 In Praise of Shamans tour?

Once again, that’s something I owe to David Torn. He did a lot of solo touring between ‘87-’88. I would go out with him and help move gear, do his tech stuff, and mix front of house. So, we spent a lot of time together on the road. Brilliant Trees was in the CD player non-stop. I was really overwhelmed by the intensity and profundity of the music on that record. And then Torn was invited to play on Secrets of the Beehive. They recorded at Miraval Studios in the south of France and Torn came back raving about the experience.

Sylvian had decided to tour again, and the 1988 tour In Praise of Shamans was to be a retrospective. Because of the dense, layered aspect of the music he had selected to perform, he wanted a strong group of musicians around him.

Torn called and said, “Sylvian is looking for a rover who can play multiple instruments, do background vocals, and play parts.” Torn has that deep improvisatory background and didn’t enjoy playing parts other people had recorded. He’s so gifted with that mercurial musical sensibility and you need to give him the freedom to be spontaneous. Why would you want to put any kind of leash on that? To his credit, Sylvian allowed the principle soloists, namely Torn and trumpeter Mark Isham a lot of leeway, and the function of the core of the group was to create a solid foundation for their explorations.

I was asked to put a demo tape together for Sylvian, but I didn’t have one. Torn said, “Make one.” I said, “I have nowhere to make a demo tape.” He said, “Are you going to let that stop you?” So, I went to my friend who owned a music store. He gave me the keys and let me go in one night after-hours to use a four-track recorder they had for sale, and I made a cassette of me playing and singing. I’m absolutely certain it was awful, but I sent that to Sylvian and his manager Richard Chadwick.

Sylvian and Chadwick were coming to New York City, and I was invited to dinner with them and Torn. We hit it off conversationally, talking about books mostly, and a few weeks later they asked me to join the tour. I was floored and will say it changed my life significantly.

In Praise of Shamans Tour, Montreal, 1988: Richard Barbieri, David Torn, Steve Jansen, David Sylvian, Robby Aceto, Mark Isham, and Jennifer Maidman

In Praise of Shamans Tour, Montreal, 1988: Richard Barbieri, David Torn, Steve Jansen, David Sylvian, Robby Aceto, Mark Isham, and Jennifer Maidman

What are your thoughts about the tour?

I have a very unique perspective because I’m the only musician that didn’t have history with everyone. I came at it with a very idealistic, wide-eyed enthusiasm. I had this “Let’s change the world” attitude. But things were going on in the background in terms of personal dynamics that I think made the tour very difficult. I tried to be respectful and careful around those dynamics and not become embroiled in them.

Musically, it was really profound, because these amazing songs incorporated so many elements including world music, ambient music, virtuoso performances, improvisatory soloing, and of course Sylvian’s compelling vocals. And we had this core of great musicians sinking their teeth into it and allowing Torn and Isham to focus on improvisation. The amount of intellectual energy that went on in organizing for those shows, including collating all of those samples, and integrating everything into the texture of the music was really astounding.

As for the playing, every night, it was like, “How deep can we go into this?” The band was also loud as hell. I usually stood onstage next to bassist Jennifer Maidman. She had a fantastic sound, but I will say she played pretty darn loud and I struggled with the volume. I was given the acoustic and nylon-string parts in several songs and that did present some difficulties onstage. Ths was before in-ear monitors. The stage levels were quite high. But we had good techs, and after the first week or so, things began to work out.

In hindsight, I think the tour was difficult for Sylvian, psychologically and physically. He wasn’t well for a lot of it. We became really good friends, and I was concerned for him. He couldn’t eat and his energy was suffering. I also think he was turned off by the whole Beatlemania thing that was going on in the background. Whenever we’d leave a theater or get on a train, he’d be swarmed by fans, which was kind of shocking to me. I had never experienced anything like that.

It was a long, demanding tour. I tried to maintain a positive attitude. I remember having discussions with him about Mick Karn, who I was by then very close friends with. I was probably being incredibly naive when I asked Sylvian, “Why aren’t you guys still working together? There’s a chapter of history you need to finish with him.” I encouraged him to work with Mick, Steve Jansen, and Richard Barbieri again once the tour was over. A year or so later they formed Rain Tree Crow. I don’t know if I was the only one suggesting they reunite. I can’t imagine I was. As everyone knows, Rain Tree Crow was a disaster and did not last, but I think they made a truly phenomenal record.

I was quite sad that my friendship with Sylvian seemed to fall away afterwards. We corresponded a lot through letters during the following years, but then that correspondance just gradually stopped. I will say working with him really affected everything I wrote for the next several years, right up to the making of Code.

Robby Aceto and Mick Karn, 1996 | Photo: Steve Jansen

Robby Aceto and Mick Karn, 1996 | Photo: Steve Jansen

Tell me about the close friendship you had with Mick Karn.

That began during Torn’s Cloud About Mercury tour following its release in 1987. Torn wanted to do that record with Mick, but Mick disappeared at the last minute, so he was famously replaced by Tony Levin. The record is by every measure a masterwork. When it came time to go on the road, Torn was able to get Mick to come out of hiding to do the tours in North America and Europe.

I knew David’s rig cold, because I had been his tech when he was touring solo. He said, “Are you free? Do you have anything going on? Do you want to be the tech for the tour?” I said, “Yes, love it.” He then said, “Wait until you meet Mick, you guys are really going to get along great!”

So, that’s how I originally met Mick. I was a gear lumper and handled the rigs for both him and Torn. Mick and I became good friends during the tour.

When I went to London to rehearse for the Sylvian tour a year later, the first person to contact me was Mick. I was delirious from travel, but he took me out to eat and we hung out in his studio.

I asked him “How is it you’re not in this band?” I was really unaware of the whole post-Japan thing, the falling outs, and the rocky personal relationships. It just puzzled me that Mick and Sylvian would walk away from the dynamic that allowed them to make such amazing music together.

But Mick did choose to guest on one of Sylvian’s songs titled “Buoy,” which they had co-written. Going back to the In Praise of Shamans tour, Mick was going to be a guest performer when we played in London, but I think it was derailed by some underlying acrimony. It was a shame that it would get in the way of what could be great music-making. So, another life lesson learned.

Mick and I instantly hit it off though during the Cloud About Mercury tour, and were comfortable talking about anything. Our interests and intellectual pursuits were really similar. We were always reading the same books. Everyone talks about Mick’s technique, innovation, and his voice on his instrument being so unique. But most are possibly less aware of the intellect behind it. Mick could discuss any subject and hours could go by and you’d still be in the thick of the conversation. He was invigorating to talk with. We’d talk about everything from Carl Jung, sculpture, art history, mythology, the perplexities of life, or some obscure author we were wild about. Books were always a huge topic.

Mick was intellectually ravenous, and really grabbed the things he found of interest 100 percent. He had one of the strongest personalities of anyone I’ve met. He’s become somewhat of a legend in my house. I tell my son stories about him. I wish they could have known each other. I think they would have really hit it off.

Mick was also funny as hell—one of the funniest people I ever met. When Mick, Steve Jansen and I were rehearsing for the tours we did with the incredible Italian singer Alice Visconti, we were staying in Concordia, which is a little town just east and south of Milan. We’d drive over to the next town every day to the theater where we were rehearsing. The route passed through a little medieval village that had these decrepit stone buildings. Every day we’d drive through it, and he’d say, “Okay, you can get that one, Robby. Steve, that one is yours. I’ll get this one.” Of course, the one he picked for himself was the only one that looked even remotely like it could be a house. It was his brand of humor, and we laughed ourselves silly. We wanted to buy all the houses in this beautiful little crossroads. It’s a cherished moment for me, which will probably sound corny and sentimental to people. Nowadays, you hear these stories of folks purchasing broken down houses in Italy for a dollar and renovating them. I wish we had had that foresight.

You only recorded with Karn once, for the Jansen Barbieri Karn Beginning to Melt album from 1993. Explore that period.

That band was originally going to be the three of them, plus me and Torn. The plan was for the two of us to go to London in 1992 to write and record some demos with them. But then Torn ended up in the hospital with a brain tumor. I was very conflicted about continuing without him, but Torn said I should go anyway and see what happens. I visited him in the hospital in New York City right after his surgery, and the same night, I flew to London, where I stayed for a month.

We just fooled around in the studio Steve had in his flat. They had previously sent me some demos and I put lyrics on them and sent them back. So, we proceeded with that material during the sessions, and wrote some new things. But it was a huge disappointment that it didn’t continue as the five-piece group as intended.

They chose to go down a different route. I think it was a matter of expediency and economies of scale. Steven Wilson was in London. Jansen and Barbieri had a good relationship with him, and it made sense that they would work with him instead. So, I missed out on doing the tours with them and the further recordings. It was just one of those things one has to accept and move on from. I think we recorded four songs, but only one, “Human Age,” was released.

Can you elaborate on your role in caring for Karn in Cyprus in 2010 prior to his passing?

The news circulated among Mick’s closest friends that he was ill. Mick was living with his family in Larnaca in the south of Cyprus, and the hospital he had to travel to in order to get his chemotherapy was way up in Nicosia. Neither Mick nor his wife could drive. So, the immediate need was for someone to help get him there for the treatments. The secondary need was to raise money to move the family back to the UK where he could get treatment under the National Health Service. Torn was living in Los Angeles at that time and with the help of Rick Huber organized some concerts to help raise money. Fans contributed as well. I think that’s what eventually helped make it possible for them to get to London.

When I got to Cyprus, Debi Zornes from Medium had just been there and she left the same day. I think Richard Barbieri came right after I left. So, there was a support network hastily put in place for Mick. It was a very intense time.

I thought my role was to be as positive and helpful a person as I could be. Mick was vaguely looking at alternative therapies as well. We went to a clinic in Aradippou to discuss them with the clinician there. One evening in his garden, Mick’s phone rang. It was Kate Bush. Knowing how much I adored her, he pointed at the phone and silently mouthed the words “It’s Kate!” with this huge grin on his face. She called to offer to help and was strongly advocating for alternative treatments. But at that point, they had discovered the cancer everywhere. So, it was a case of trying to arrest the growth and see if there was anything that could be done. But there wasn’t.

Mick passed away in London. I didn’t get to London during his last weeks, but we said goodbye there in Cyprus. I had to drive to the airport to get a super early flight to Athens, so we stayed up all night talking. Then the cab came, and we said goodbye and that was the last time I saw him. It was heartbreaking. I came back home just completely emotionally leveled. A few months later, I went to London for the funeral.

David Torn and Robby Aceto, 1988 | Photo: Robby Aceto Collection

David Torn and Robby Aceto, 1988 | Photo: Robby Aceto Collection

David Torn has been a core presence in your life for 50 years. Reflect on that relationship.

As we discussed, I’m smack dab in the middle of upstate New York in the Finger Lakes region. It’s very, very beautiful here, but somewhat remote. I started spending time here after college. David was one of the first people I met. When I got there in 1974, I knew only one person, and he said, “Do you know The Zobo Funn Band?” I said, “No, I haven’t heard of them.” He responded, “Well, those guys live down this little side road. Go knock on the door. You’d like them and I know you would get along well.” So, I did that.

I rolled up unannounced. David answered the door. We looked at each other, and it was like, “Wait, I totally know you.” We instantly became friends. As you said, we’re talking about a 50-year friendship. I have a hard time getting my head around the idea that so much time has gone by. We still pretty much act like adolescents when we’re around each other.

David has had a profound effect on my life. It’s something indescribable. It exists across every stratum from rarified intellectual, musical pursuit, and the prickly career stuff, all the way down to the really subterranean, human core in terms of the things that make you tick. It’s a friendship at a level one doesn’t encounter very often.

I even married David and his wife Linda. When they decided to get married, they said to me, “We want you to do the ceremony.” So, I remembered there was a classified ad in the back of Rolling Stone. You wrote away, sent in a little form, had a telephone discussion with someone you didn’t know and became a “mail order minister.” So, I got the credentials, and I married them during a hippie wedding out in a field overflowing with family, friends, and flowers. I think eventually they went to a Justice of the Peace in New York, just to be on the safe side.

From a musical perspective, meeting David galvanized for me a lot of what I had been searching for, as I was just beginning my fascination with amplified guitar. He also introduced me to ambient looping. When we first met, I was already obsessed with echo, or delay, or whatever you want to call it. I had an old tape echo I found in a garage sale that I was using. David borrowed the device a few times, and we explored the idea of using time and repositioning it in small or large increments. As the technology expanded, there was that gradual shift from analog to digital and the delay times began to get longer and longer. It was like this technology came along right at the perfect moment. He got deeply into it and embraced it as a core feature for improvisation, and shared his method with me.

I found the use of ultra-long delays magical and captivating. The ability to shift a musical utterance in time and work with the randomness of it remains a center of fascination for me. Some people say “looping” today and it’s just meaningless. As typically practiced, it’s just about playing phrases, locking them in, and there’s your song. But I’m talking about looping as it informs composition and improvisation. There are only a handful of practitioners I know of who are doing that, but it’s the approach I’ve adopted. So, he was very important as a mentor to me during a crucial formative period, as I was learning who I was as a guitarist and realizing my identity.

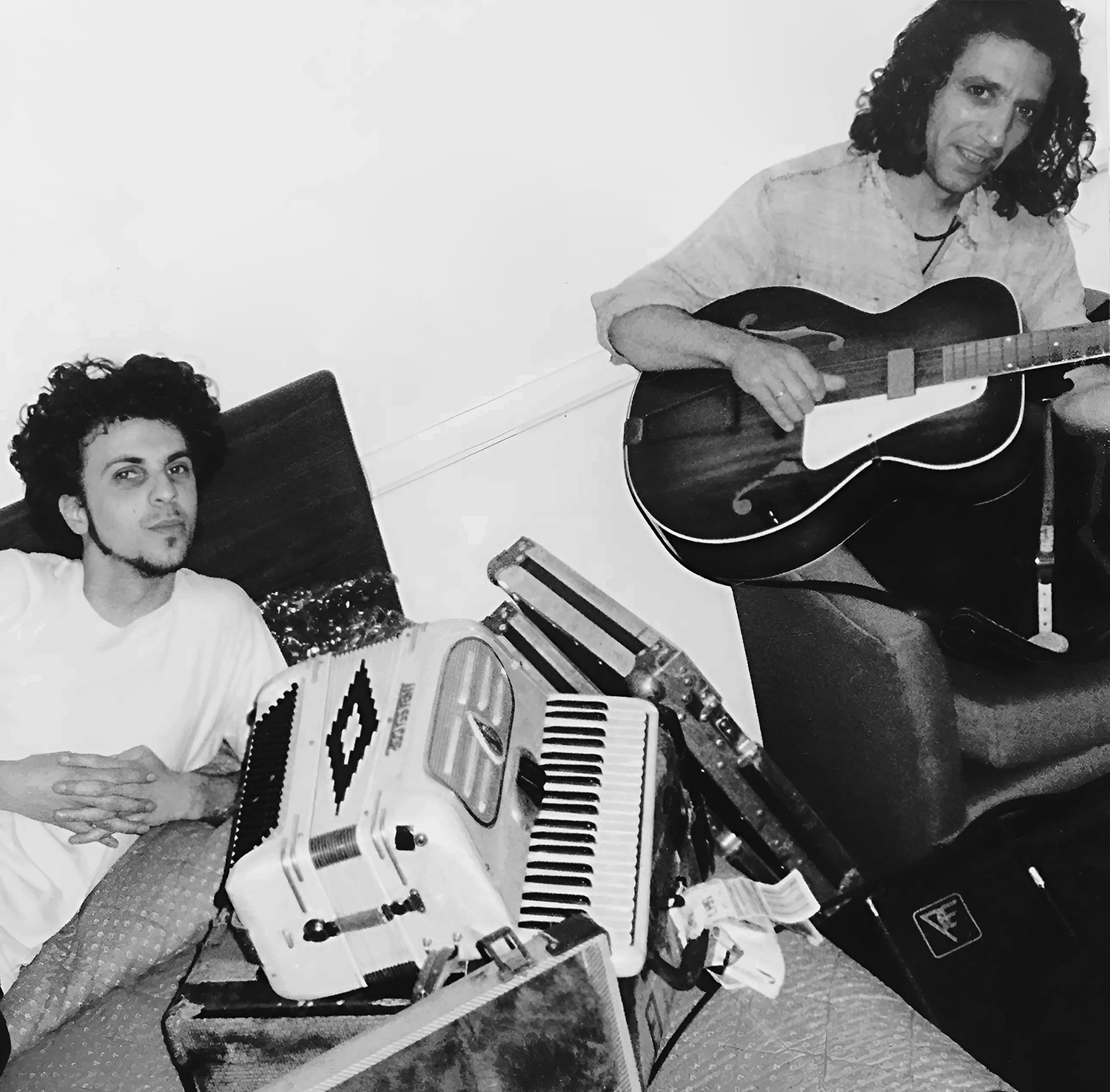

Douglas September and Robby Aceto, 1999 | Photo: Robby Aceto Collection

Douglas September and Robby Aceto, 1999 | Photo: Robby Aceto Collection

You’ve played a significant role across Douglas September’s output. Discuss the work you’ve done together.

He’s an absolutely amazing artist and truly one of the best human beings I’ve ever known. In terms of his music, a journalist somewhere along the way referred to him as a “post-apocalyptic balladeer.” It’s a phrase I think in a lot of ways is quite fitting. He takes impressions and observations about contemporary society, family life, dogs, the dystopian trends we seem to be living through, and looks at them through a very grassroots sensibility. He’s like Woody Guthrie or early-days Bob Dylan, but filtered through a lens of Harry Partch, Bukowski, urban chaos, and the French Symbolist poets. Partch was known to refer to himself as “a philosophic music-man seduced into carpentry.” which I think might also describe Douglas fairly well. A complex individual and fabulous artist.

Again, I’ve got David Torn to thank for meeting him. In 1998, David played on Douglas’ Ten Bulls album, which was produced by Michael Shrieve. Frisell was the main guitarist on it, and David did all this beautiful textural stuff. Douglas’ label Gold Circle wanted him to put a band together to tour it. David was unavailable, so he recommended me.

I drove up to Syracuse to hear Douglas do a solo set at a coffeehouse, and hung out with him and his manager Tony Boone, who was also his best friend from childhood. His set was really good. It was just him in balladeer mode with an acoustic guitar. He’s from Cape Breton and is a real poet, so he comes to this tradition honestly. But he’s seen a lot of the world and also has that cynical edge.

His voice and ability to inhabit a character struck me as something definitely of a different order than your typical folk singer. He was coming from some other place entirely and using the style of music to channel characters. I saw amazing potential and instantly wanted to work with him. I put some musicians together, who were basically the rhythm section from Red Letter. The three of us had spent so much time playing together and had excellent chemistry, so we just got together and shedded on Douglas’ songs for a couple of days. When he and Tony arrived from Toronto, we were able to just add him into the mix and within a day or so of rehearsals, we had this beautifully-functioning band. It was just marvelous. We rehearsed for a couple more days, and the tour was supposed to commence the next day at The Living Room in New York City.

Ithaca is famous for its spectacular gorges, and most everyone knows to exercise a lot of caution. To my never-ending anguish, I never mentioned to them to be careful walking at night, as their hotel was right in the middle of Collegetown, which is a part of the city bisected by these deep gorges. That night, Tony, who was unfamiliar with the area, met with a horrible accident. While walking back to their hotel in the rain, he slipped and fell to his death in one of the gorges. They had been walking on a municipal footpath after these torrential June rains we had that Spring. The river was swollen and everything was drenched and slick. He lost his footing and went over the side. It was just an absolute life-altering tragedy.

After living through a disaster of that proportion, what had been a fun, new friendship, in a matter of moments took on another level of significance. This is not something you encounter often in life. There was a police inquiry. We spent hours talking to the detectives going over what had happened. It was morning when we finally left the police station. We went back to my house. My wife made up some beds and we tried to get some sleep. I gave Douglas a shirt to wear. You’ve heard that expression “forged in fire” about certain friendships. This was definitely that.

As for the tour, everything went on hold. All the venues that had been booked were very sympathetic and allowed Douglas to reschedule. A couple of months later, we reconvened and carried on. We played some great gigs including showcases at The Bottom Line, and some live radio appearances. It was a terrific band. But the dynamic was altered in that Douglas had to be more in charge of his own management. That is just a really difficult thing to try to do.

His label wanted him to do another record right away using the band. We went to Los Angeles in 2000 to cut the basic tracks for what would become his album io. But Douglas had been paired with a producer who I don’t think really understood who he was. Fortunately, Douglas was able to get control of the masters and he came down and we mixed much of the record here in Ithaca.

When it came time to support the release, I don’t think they wanted to spend the money to put a band on the road. It was suggested that Douglas and I should go out as a duo, which is what we did. We played our first gig with that configuration in a theater in Ottawa with almost no rehearsal. I think we were both surprised at how good it was. Eventually we toured the UK, Europe, the US, and Canada as a duo. Everything sounded very fresh and very unusual. We completely overhauled his material, using ambient effects, tape recordings, and distorted microphones to create these intense, immersive atmospheres.

The two of us started writing together. He’s a dream collaborator. You can lay down a deep, one-chord blues riff on a fuzzed-up guitar and suddenly he’s right there howling these wild lyrics like a beat poet on a week-long bender. It’s instant fabulous music.

After a bunch of touring, in 2001 we made a live-in-studio record with David Torn that Douglas cryptically titled Oil Tan Bow. We set up at David’s studio just as we would on a gig, and started playing. We had the best time working together. Douglas took the mixes back to Toronto and went to work crafting these incredible interstitial-like pieces to weave the whole thing together. Then Douglas and I went out and did some more touring on the back of that release.

Back in Toronto, Douglas started organizing his own recording studio which is now a terrific place to work. He’s been doing some producing and building bespoke electronics. On top of all his other talents, it turns out he’s totally incredible at tech stuff. He has been collecting vintage gear and is fearless when it comes to opening up a piece of gear like a tape recorder and fiddling with the circuitry.

He went on to do another album called Sundays in Radio, which he self-produced. We were both immersed by then in family life and spent a lot of holidays together, but only collaborated on that project remotely. I played on a lot of it. He also has a new album called Rare Breeds which I hope comes out sometime soon. I played on it as well. It’s even more vicious in its social commentary, with all the heavy sarcasm and the insightful, cutting perceptions typical of Douglas.

Photo: Rebecca Proctor

Photo: Rebecca Proctor

Since you began your career, the music industry has transformed into a social media-driven, algorithm-based, streaming universe. What’s your perspective on that?

To be honest, I hardly recognize the landscape. I’m from the era where you’d go to a record store, browse, touch, and feel the records, and listen. That’s one of the ways you would discover things. With streaming for instance, that tactility has been completely eliminated from the experience. Today, listeners consume music in soundbites. It’s about consumption, like eating a Big Mac, which is filling but not sustaining. It’s all about corporate regurgitation and the cult of personality.

In terms of social media, previously, we could appreciate a recording without knowing anything about the musicians or asking “I wonder what they’re up to today? What kind of makeup are they wearing?” and clicking on their feed to find out. I feel like this is what people are buying now, as opposed to buying music. Music has become mostly an empty gesture to a lot of people. You’re lucky if they listen to the first 30 seconds. Thirty seconds is enough for a lot of people. And then they scroll to the next thing in their feed. To me, this is a strange way to appreciate music, as a cosmetic appurtenance. It’s like buying artwork to match the curtains.

With physical media, there was an investment involved. You held the album in your hands. You didn’t just “stream” it, you owned it. You could mull over the thing as a piece of art, in tandem with the sounds captured in the media. Over time, as you revisit it, you might think, “Isn’t it fabulous how these words work together and how the artwork relates to the music?” One of my favorite records of that time was Laura Nyro’s Eli and the Thirteenth Confession. The inside of the sleeve was perfumed. That seemed so crazy and intensely personal, but very... wow.

I still feel connected to the time when if you had respect for a musician or a feeling for the work they did, you might want to appreciate it and experience it in the way it was intended. This usually involves something like thoughtful listening, which takes time and concentration. It’s like reading, which is also one of life’s great treasures that has gone by the wayside for so many people who just don’t bother to do it.

I’m fortunate in that I have managed to avoid the necessity of selling records, or the survive-by-touring part of today’s music scene. The thing has really come collapsing down on the artists. I still believe in making long-format albums, but don’t support myself through the release of them. I try to earn a living scoring documentary and narrative films, collaborating, and playing sessions. My wife also works, so we’re lucky to be a two-income family.

Music remains extremely personal to me. And it’s about the music. I’m not concerned with “How is it going to work in the industry? How is it going to stream? Will it hook people in the first 30 seconds? What if it doesn't?” and “Gee, I hope people think I’m cool or something.” I’m not building my music according to how people use their mobile devices. I simply won’t allow those considerations to leak into the conception or production of my music. A mobile device is a delivery system and there'll be a new model to replace it next year, whereas music is an absolute and irreplaceable.

I’m just more focused on the music, not on trying to be a personality, or maintaining a well-curated Instagram. For instance, having been in David Sylvian’s band might get someone interested in me because I once worked with him. But I’m extremely uncomfortable with that. It feels like name dropping. I just never mention it. I’m uncomfortable even now, talking to you about it. I don’t feel special, I just do what I do out of a compulsion to do it. I’ve had to find a way to make it possible without the benefit of larger success. Listen, or don’t listen because if you’re not interested in actually listening, then I’m probably not making music for you.

The Birds Through Fire guys are perplexed by my attitude, because they understandably feel making those associations would perhaps help increase awareness of our music. But as much as I want more people to hear it, I wouldn’t try courting an audience by using someone else’s celebrity. It’s just bad form.

What motivates you to be a creative entity?

Society has changed in so many ways that are, for the most part, incredibly negative. Somewhere there’s a quote that goes “All art is a political act. If it’s not in some ways political, it probably isn’t art.” And I really believe this is true. So, a creative life needs to be lived in response to your time on Earth. At the same time, I think being able to insulate yourself from all of that, disconnect from all the noise, just sit at an instrument and try to connect with some sense of discovery, and go into that universe of possibility and invention that attracted you to playing music to begin with remains incredibly important. Keeping your health together, staying connected to your family, making dinner, and walking the dog are also things that are important.

And oddly enough, I’m still ambitious.

When my son Alexei was born, it was during my “professional musician” period. I could have easily gone on for the next 20 years doing that. But you can’t be a musician in a vacuum and I wanted more to be a decent dad, a complete person, and it made me refocus my energy. Now, I just hope to complete a body of work, both in the form of performances I’ve realized, and in pages of notation.

Given the level of Alexei’s talent, he’s like a sounding board for me. He can play this Nth-level piano music by Schumann, Brahms, Rachmaninoff, Bartok, and Liszt because he’s put in the massive amount of work necessary to do that. He’s a fully-realized pianist and he has this capacity and depth of musical understanding that I find terrifically exciting. So, I want to keep talking with him about that and the effect it has on him, including what he discovers about it and through it. I’m also interested in his thoughts about other musicians, other periods in time, and other ways of living in the world. It’s not just about me being the old man going dotty who he needs to humor. Rather, he’s able to point to some of the things I’m doing and relate to them from his perspective. And that keeps me interested in trying to get better at doing it, and possibly making music worthy of his effort.

It’s difficult to imagine doing anything else. I’m usually writing at the piano these days, but I keep my hands in shape for the guitar. There’s no way to read all the books and listen to all the music that you want to absorb in your lifetime. So, you have to say, “What do I have time for? Can I stay focused long enough this week to finish this piece?” Can I make time to walk the dog this afternoon?" So, maintaining direction as a creative entity as long as I can sustain it, and walking the dog, are the priorities.