Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Sharna Pax

Oblique Reality

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2025 Anil Prasad.

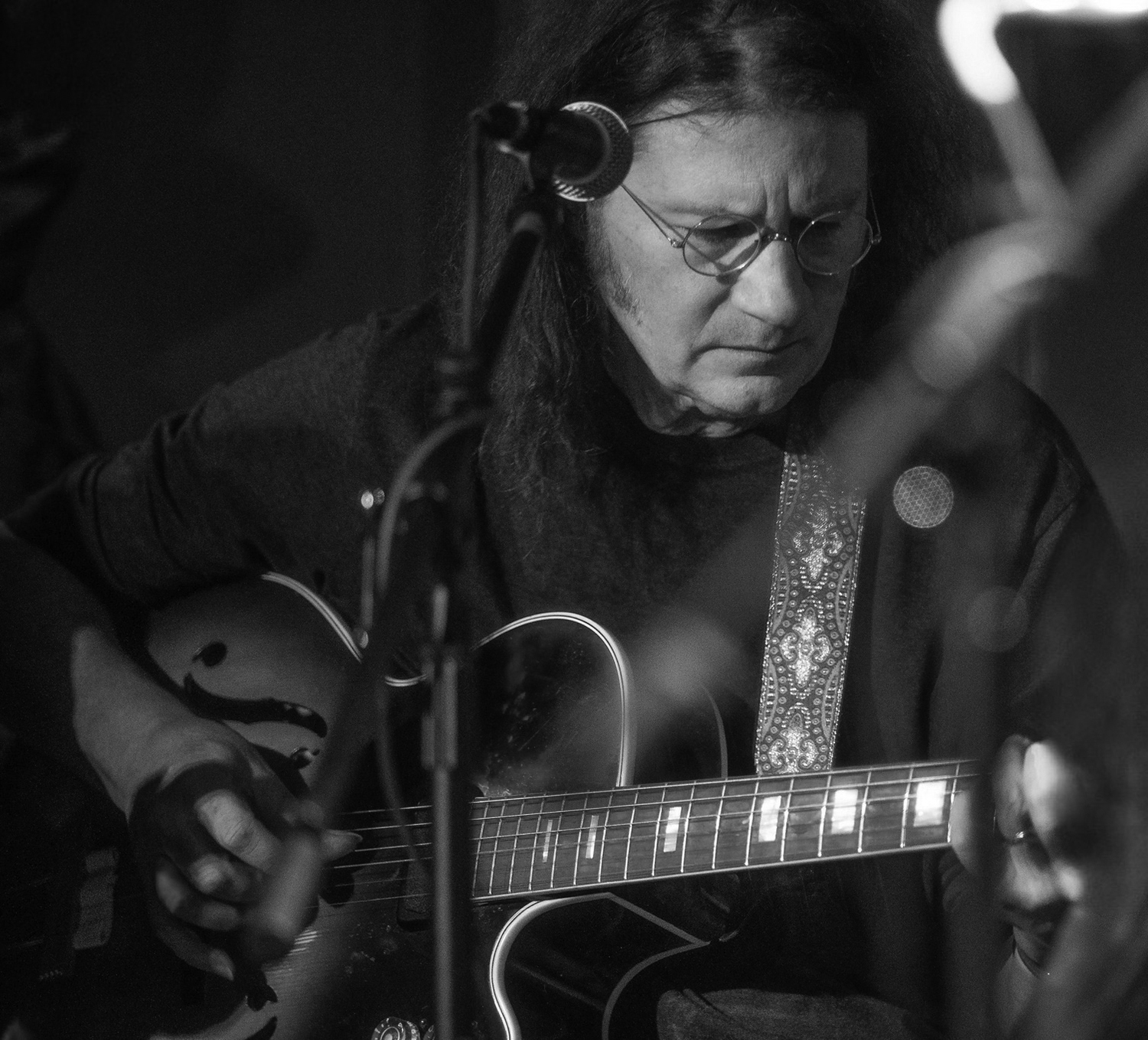

Sharna Pax: Mike Tittel, producer Brian Lovely, Hallie Menkhaus, Dave Ramos, George Cunningham, and Peter Obermark | Photo: James D. CampbellSharna Pax’s Peter Obermark writes provocative songs for grown-ups.

Sharna Pax: Mike Tittel, producer Brian Lovely, Hallie Menkhaus, Dave Ramos, George Cunningham, and Peter Obermark | Photo: James D. CampbellSharna Pax’s Peter Obermark writes provocative songs for grown-ups.

The Cincinnati-based singer-songwriter, vocalist, and guitarist delivers razor-sharp lyrics about the nature of existence, ambitions achieved and lost, prioritization and perception, what's in our control and what isn't, and the toxic influence of tribalism on our lives. And yet, even with the highly literate, informed cynicism that often colors his songs, he still brings cautious optimism to the table, and the hope that there’s a more positive way forward.

Sharna Pax features some of Cincinnati’s finest musicians, including lead guitarist George Cunningham, bassist Dave Ramos, lead vocalist and guitarist Hallie Menkhaus, and drummer Mike Tittel. Together, they’ve infused Obermark’s songs with adventurous, mercurial rock, pop, and roots arrangements, full of engaging twists, turns, and ornamentation.

The band just released its debut album The Way We Live Now. It was produced and mixed by Brian Lovely, another Cincinnati luminary revered for his own solo albums and virtuoso guitar work.

Sharna Pax is inextricably linked to a previous group called Copper that recorded three albums between 2014-2019. The band included Obermark on lead vocals and guitar, Cunningham, Ramos, and drummer Chris Arduser, known for his work with The Bears, Psychodots, and The Raisins. Arduser passed away in 2023, resulting in the remaining members choosing to establish a new band, while retaining much of the spirit and spark of the prior ensemble.

Innerviews visited Obermark at his colorful, elegantly-appointed home in Cincinnati to conduct this interview. As with his songs, Obermark offers piercing, incisive perspectives about the world around him in conversation. He also has a professorial air about him, which isn’t surprising, because he literally is a professor.

Obermark has taught at The University of Cincinnati and The Art Academy of Cincinnati, specializing in social sciences, humanities, and history. And within those contexts, he's fearless about engaging his students on the corrosive societal fissures we’re encountering at every turn in modern life and empowering them with ideas to transcend and address the issues. In addition, Obermark previously served as a licensed paramedic and EMS professional for more than 20 years.

Photo: Plan B Images

Photo: Plan B Images

You have a unique background between your life in academia and your experiences as a paramedic. Discuss how that influences your music.

For a lot of my life, I've taught literature, languages, humanities, social sciences, and interdisciplinary studies. Most recently, I’ve been teaching at the Art Academy of Cincinnati. It’s a wonderful institution that has always given me wide latitude to create multidisciplinary courses that reflect things that I'm interested in.

At the Art Academy, I’ve been teaching courses on the history of totalitarianism, and one called “The Apocalyptic Imagination,” which is a social history of the idea of the apocalypse. I also teach a course on the history of dystopia as artistic and intellectual concepts. In addition, I teach a course on modern war, which looks at the way that warfare has evolved over the last century and a half.

I only learned recently that behind my back a lot of the students nicknamed me “Dr. Death” because there's kind of a recurring, kind of gloom and doom theme that runs through a lot of these courses. [laughs]

I spent about a decade riding on an ambulance as a paramedic back in the early 2000s, and then I taught in a paramedic program for about 10 years, training paramedics.

My squad was responsible for some of the worst neighborhoods in terms of crime and poverty in Cincinnati. On a regular basis, we dealt with medical illnesses, gunshot wounds, stabbings, drug deals gone bad, domestic violence, and spousal abuse.

You see a lot of ugly things riding on an ambulance in those areas, and we had a lot of close calls. There are a lot of guns around in this country, and many people have one, so we never knew when we rolled up on a scene what was going to be waiting for us.

When it comes to working on songs, I invoke the old adage they tell writers, which is “write what you know.” And that means there’s always a real battle happening. I always feel like I'm walking the line between cynicism and even despair about certain facets of life and existence. But at the same time that's always coupled with my love for my friends and family, and my care and concern for us as a species.

I feel like that's a tension that never gets completely resolved when I'm trying to write. There's always a part of me that’s ready to give in to despair and that's always butting heads with the part of me that wants to embrace the good things about this life that I would like to write about.

When did you first begin writing songs?

I started during the period of being a paramedic, around age 50. During that time, I was good friends with and an avid fan of Chris Arduser. Chris was a legendary character on the Cincinnati music scene. He was a superbly talented drummer, multi-instrumentalist, and songwriter.

Around 2006, when I was heavily involved in paramedic work, I would hang out with Chris on a regular basis. We’d talk about music and movies. Chris was a fascinating raconteur and conversationalist. I think talking to him so frequently about music and seeing him perform were huge catalysts for me to want to write songs myself. Other local musicians like Brian Lovely and George Cunningham who I was also friends with, who also knew and worked with Chris, also inspired me to write songs.

Doing emergency medical work really started to wear on me, psychologically. And that shift intersected with me actively following these great musicians. I realized I needed an outlet to come to grips with the things I had seen. And that combined with a period during which my son was facing a lot of medical challenges. So, all of that made me gravitate towards my first tentative jabs at songwriting.

Initially, I didn’t have much success. I didn’t really know what I was doing. I have been playing guitar since my twenties. I’m entirely self-taught and never had a lesson. But I’d use the skills I had and record drafts on GarageBand and send them to Chris. And anybody that knew Chris knew he was blunt, to put it mildly. Chris would never tell you something because he thought you wanted to hear it. He was brutally honest, and he was very quick to tell you if he didn’t like something.

So, Chris was a good sounding board. I’d keep sending Chris song drafts, and for the first few months, he’d say, “Yeah, keep writing.” That was his way of saying “You’re not there yet.” He would also critique the songs and tell me why he thought they weren’t working.

In 2007, I wrote a song called “New Hope for the Dead” and sent it to Chris. I got an almost immediate response from him. He said, “Okay, let’s talk.” And from that point on, Chris was very encouraging, and I started to write and record more. By 2011, I had enough material together and Chris said, “Why don't we take these into the studio and start working on them?”

We partnered with Matt Hueneman, a local sound engineer and producer that’s very talented, and began working on the first record that was eventually put out under the band name Copper. And that album was called Fade to White, which came out in 2014.

So, “New Hope for the Dead” was the first song I wrote that went on to be recorded. But the truth is, I wasn’t very happy with how the song came out on Fade to White. I didn’t like how it was executed, and it was entirely my fault. That’s why we decided to revisit it on the debut album by Sharna Pax. I really wanted another crack at it so we could really do it justice.

George Cunningham, who was the lead guitarist for Copper, and now for Sharna Pax, agreed. He suggested we change the key so Hallie Menkhaus, the lead singer for Sharna Pax, could transform the vocals. We also came up with a different arrangement. We’re all much happier with the new version.

Photo: Plan B Images

Photo: Plan B Images

Two more Copper albums followed Fade to White, which are Cincinnati all-star musician records. Explore the journey you went on with those.

I never would or could have put out any of those records had it not been for the fact that I was friends with so many great musicians before I started writing songs. I knew people like Chris Arduser, George Cunningham, Brian Lovely, and Bob Nyswonger for years, socially. I met them because I was a fan of their music and by going to their gigs.

When I finally did start writing songs, I knew right away it was going to be sink or swim, because of the standards these musicians had. I was blessed and fortunate in every way, because all of them were so encouraging and took me seriously. They agreed to do the records. I could never have made them without them.

The second album was The Devil You Know and the third was Number Six Girls School. By the time we made those records, Chris and I were spending a lot of time together. I would make lots of demos and Chris would critique them, and make suggestions for arrangements, chord progressions, and melodies.

One of the songwriting tricks I learned from Chris was the practice of taking really grim subject matter and putting it in a happy, poppy, upbeat setting. He was doing that in his solo work and output with The Bears, Graveblankets, and Psychodots, too.

You’ll hear that approach on the title track of Fade to White, which is a true story about one of my patients, who was 19, that was shot multiple times and then run over by his own car in a drug deal that went bad. We were the responding crew and worked very hard to keep him alive on the way to the hospital, but we lost him. When we got to the hospital, I had to talk to his mother, who was waiting to find out how her son was. Again, Chris showed me how I could transform that topic matter into something that was also musically interesting. I kept that in mind for those subsequent two Copper records.

Every record I’ve ever done, including both Copper and Sharna Pax, also has a song that’s about my son Nathan. He’s 38 and is profoundly disabled. He was born with severe cerebral palsy. So, some of my songs are about my life with him and the experience of being a father to a son with those challenges.

On those Copper records, you’ll also hear a couple of love songs for my wife Sherri, and some macro-level observational songs about the world at large, including the broader injustices and tragedies occurring.

I think the Copper records got better and better. I really think the third record is strong. The title track, “Number Six Girls School,” is a true story about the cultural revolution in China under Mao Zedong and the atrocities that were inflicted on the population during that era. It’s a song about ideological rigidity and fanaticism. Number Six Girls School was the name of a school in Beijing at the beginning of the revolution. I wrote the song after watching an interview with a Chinese woman who was the principal of the school. She discussed being dragged away by young, ideologically-fanatical members of Mao Zedong’s brigades, and being beaten, and then sent to reeducation and forced labor camps. I was very moved by that story and wanted to capture it in the song.

Live performances accompanied the release of Fade to White. It’s rare for musicians to do that for the first time in their fifties. What was that like for you?

Actually, I was in my late fifties when we did the first show as Copper. Initially, I didn't think it went well. I had terrible stage fright, but it’s better now.

The only way I could get myself up in front of an audience was by surrounding myself with incredible people like Chris Arduser and George Cunningham. They helped me cover my shortcomings during those early shows. They were really white-knuckle experiences for me, but things got better by the time the second album came out.

By the time of the third record, I started to feel, “You know, I can do this and not fall on my face.” [laughs] I was essentially an amateur musician at that point, but I was working with A-list professionals. Having them express confidence in me and saying, “You’ve got this” went a long way in calming my nerves and making it work.

Copper, 2015: Peter Obermark, Chris Arduser, and Matt Hueneman | Photo: Tanner Hinds

Copper, 2015: Peter Obermark, Chris Arduser, and Matt Hueneman | Photo: Tanner Hinds

Explore why Copper came to an end, leading to the formation of Sharna Pax.

When we were making the third record in 2017, Chris Arduser’s alcoholism was starting to really become apparent. Most of his friends knew about it and Chris was pretty open about it. He was really an open book. I had a lot of conversations with Chris about it and he was never able to really articulate what was driving this really rapidly accelerating alcoholism. And it was starting to affect his performances.

I really tried to convince Chris that he was someone lovable completely apart from his extraordinary gifts as a musician. But it didn’t change his behavior. No matter what I did to try and help him, I couldn’t. Many, many other people who were as close or closer to Chris also tried and tried.

Finally, I had to consider the questions, “Am I helping to enable this behavior? Should I tell him I can’t work with him anymore unless he gets sober? If I do that, will it drive him even deeper into despair?”

Eventually, I decided, “It’s too painful to be around this.” I talked to Chris and said, “I can’t do this anymore. It hurts me too much to watch you do this to yourself.” And he took it with calm grace. A lot of musicians had said that to him by that point.

Chris had a couple of stints in rehab. He would call me from time to time from rehab to talk about books or politics. We had a thousand interests in common. But the day I felt it was over was during one of those conversations when Chris said he had sold all of his musical instruments and was never going to play music again. I felt he was telling me he was giving up on his life.

Chris died in September 2023. He was truly a generational talent. He was a brilliant songwriter, drummer, multi-instrumentalist, and producer. To watch him succumb to his addiction was an incredibly depressing thing.

When that happened, I had written songs for another album. But Chris had been such a core, integral part of Copper that I didn’t have the heart to use the name. It didn’t feel right. So, I let some time pass and then talked to George Cunningham. We decided, “You know, let’s start something new." And that became Sharna Pax.

Provide some insight in putting Sharna Pax together, leading to recording its debut LP.

George and I thought about who would be ideal. We felt Dave Ramos, the wonderful bass player from Brian Lovely’s Flying Underground, who had also previously played with Copper, would be great. And I thought my niece, Hallie Menkhaus, who had done some backing vocals on Copper records, would be the perfect lead vocalist. She has a fabulous, classically-trained voice, and is a lot of fun to be around. She’s just 24 years old, but is an old soul with an appreciation of rock music from the ‘60's-’90s that’s rare to find in someone so young. On drums, we knew the amazing Mike Tittel would be great for the band, but he’s so busy that we thought he'd say no, but he agreed to join. He’s one of the few local drummers that Chris Arduser considered to be a peer in terms of technique and musicianship. So, we had a crew.

We were originally going to record at Audiogrotto studios in Newport, KY with Matt Hueneman, who had co-produced all of the Copper records with Chris Arduser, as well as serving as sound engineer. Matt had been a really central part of the Copper sound, but he was incredibly busy with big clients and corporate work, which needless to say, pays a lot better than broke-ass Obermark. [laughs] I totally understood.

Then I thought, how about if we got Brian Lovely? He has his own Beat Parlor studio and is a fantastic producer. I had been friends with Brian long before I started writing songs. So, I asked him, and he instantly said yes, and we started recording.

I had 20 finished songs ready. We started chipping away and worked on it until we had nine finished songs. And when we pulled the trigger and finished the record.

Photo: Plan B Images

Photo: Plan B Images

Elaborate on how Lovely contributed to the record’s sound.

I wanted to wander off into a little bit of a Brit power-pop direction for some of the songs, and that was right up Brian’s alley in terms of his sensibilities. He had an immediate intuition when I sat down with him to explore the way I wanted the record to sound. And from that point on, I barely had to even have a conversation with him about it.

Every recording session with Brian was an education in terms of how he worked, how he thought about songs, and the ideas he’d bring to them. He’d come up with things that would never have occurred to me.

For instance, on “I Am Ray’s Brain,” the original version was a little more of a straight-ahead rocker. Brian listened to it and said, “The drum track really needs to be more kinetic.” Mike Tittel came in to record the drum part and Brian and Mike strategized on how to do it. They decided, “Let’s go Keith Moon on this.” So, they went wild and gave the song a force that was lacking in the original. I could tell a similar story for every song on the record.

Because Brian is a major musician and songwriter in his own right, he would be listening to mixes and say, “I’ve got a guitar hook that would sound really great here.” And he’d just add it, and it would be amazing. It was such a blast.

Everyone had such a good time making the record. We were all giggling like children by the time it was over. We were so happy with how it came out.

The name Sharna Pax comes from Russell Hoban’s sci-fi novel Riddley Walker and translates into “sharpen the axe.” Why did you choose it?

The novel has a devoted cult following. It’s a post-apocalyptic story set in rural England, thousands of years after a nuclear apocalypse has wiped out most of civilization. When Hoban wrote it, he created a bastardized dialect of English and the whole book is written in it. He imagined a post-literate society that had been bombed back into the Iron Age. And of course, English was going to change as a result of that.

In the novel, there’s a subplot that involves people being beheaded by an executioner. And the phrase “sharna pax” refers to preparing for the execution. I later learned that in present day rural Kent in southern England, some locals actually will say “sharna pax” instead of “Did you sharpen the axe?”

So, I thought it was an interesting name. George and I also liked the idea that people might think Hallie’s name is Sharna Pax. [laughs] It sounds like a 21st Century pop diva.

Let’s discuss a few songs, beginning with the title track “The Way We Live Now."

It was written at the end of the pandemic when things were starting to wind down and I realized how profoundly our society had changed as a result. And what we’ve got is probably what we’re going to have for the foreseeable future.

The song discusses political dysfunction, anti-science hysteria, repression, nativism, and racism, which began intersecting in American culture during that period and continues. I was trying to capture what many of us are feeling and seeing in everyday life.

Photo: Plan B Images

Photo: Plan B Images

“Infants in Arms” looks at a more personal experience.

It can be very sad sitting in an airport at Christmas time waiting for your flight that’s running late. That’s where I found myself some years ago after a relationship had broken up. Cops were running around with drug-sniffing dogs and kids were playing video games while their dads were getting drunk. The whole thing felt so preposterous. It was like living through a parody of a bad Hallmark movie.

I was at Pearson International Airport in Toronto. Finally, we were boarding, and the overhead speaker said, “Boarding priority will be given to anyone with infants in arms.” That’s where the title came from.

We’ve all probably experienced some version of this in our lives and that’s what the song captures.

“Infants in Arms” almost didn’t make the record. We were running out of time to hit the deadline for mastering. In order to get it on the record, George Cunningham, Brian Lovely, and I knocked out the track in a single afternoon session, unlike the others, which took a very long time.

We talked about how the new version of “New Hope for the Dead” came about, but let’s explore what the lyrics delve into.

It came out of chance encounters with a well-known homeless man in Cincinnati. It was near the University of Cincinnati where I was teaching at one point. After several encounters, I put his story together and understood he had been an inpatient at a nearby psychiatric facility. This was before the government closed down all the residential psychiatric facilities and put people out on the streets, gave them 30 days worth of meds, and said “good luck.” He was one of those people.

He lived in the woods next to the university at a local park. He’d go marching up and down the streets with a white sheet over himself, holding a long pole he cut from a branch of a tree he had wrapped with tin foil. He also made quasi-religious head dresses and necklaces that he wore. Depending on the day you talked with him, sometimes he thought he was Jesus, sometimes he thought he was Moses.

One day, I was walking down the street, and he came out of the woods in a non-threatening way and wanted to talk. I stopped to give him some money, which I usually did. And he started this free association about how the world was going to end soon and nobody seemed to understand what was going on. He said he was a prophet that was trying to get the word out to everybody, but nobody would listen to him. It was simultaneously bizarre and kind of made sense.

I got the phrase “new hope for the dead” from an old Reader’s Digest. That publication used to run articles like, “New Hope for Disabled Veterans” or whatever it was. So, the title was a parody of that kind of bright, chirpy optimism. I used it to communicate the threads of the conversations with this man, and his wild, free association of apocalyptic visions.

“Churches in China” has a provocative title, but it’s actually about something endearing.

It’s about neither churches, nor China. This has caused no end of trouble when we play it live. People come up to me and lecture me about how “There are no churches in China.” I’m like, “Dude, listen to the lyrics please.”

I wrote it after a spectacular, crisp, cloudless fall day. I had taken my son Nathan in his wheelchair out to a local Cincinnati park called Ault Park. It’s a really beautiful place and is where I got married.

I had brought a picnic lunch and a book to read, which was The Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen. It was a perfect afternoon full of beautiful, glorious colors as the sun went down. Everyone was in lovely spirits.

So, we were reading the story, and Andersen, being the European colonialist he was, set it in China. But he’s referencing churchyards, without it dawning on him that China probably didn’t have a lot of churches at the time he was around. I joked with Nathan, “What do you think about that? Churches in China? Isn’t that funny?” And he thought it was.

The song is about what a wonderful day that was and being in the moment, bonding over this story, and contemplating the tension between what is beautiful in this life, and the knowledge that it’s all temporary, and that even the most beautiful of things always come to an end.

“What Makes the World Go Round” is the only song on the album you didn’t write. Tell me about its origins.

It was written by David Surface, a very talented author I’ve known for decades. He’s also a great songwriter, bassist, and guitarist. He often works with Bill Lloyd, the Nashville songwriter and guitarist who's known for his work with Foster & Lloyd, and has many well-regarded solo albums.

David and I sometimes trade drafts of songs we’re working on to critique them. One day, he sent me a rough mix of “What Makes the World Go Round” that he and Bill had recorded. It’s a very stark story about temptations of the flesh, and the corrupting influence of money and power. I loved it right away and asked David if I could record it and he generously agreed.

It was a great day for me when we sent him the master and he said that he loved it, and commented on how great George Cunningham’s fabulous guitar solo was.

Photo: Mike Howard

Photo: Mike Howard

Preview the second Sharna Pax album you’re working on.

First, I’m pinching myself that we’re going into the next Sharna Pax record with exactly the same lineup—and producer—that we had for the first one. These are all busy professionals with multiple bands and commitments, and I’m grateful that they’re all willing to make time for this next foray.

The songs are already written, and as with the debut album, they're a mix of personal experiences and broader cultural observations. I’ve written most of the songs for Hallie’s voice.

We’re starting off the next round of recording sessions with a song called “Press 1 if You’re in Pain." It’s grounded in true stories about trying to access medical care in America’s Kafkaesque, for-profit system.

As with the first record, musical styles vary a lot from song to song, and include Brit-pop, jangle-pop, roots rock, and Americana. George Cunningham and I are also co-writing a gypsy jazz tune about the burlesque scene in 1950s New York city, and we’re having a lot of fun with it.

How do you strike a balance between providing a provocative perspective without sounding like you’re proselytizing?

That’s something I learned from Chris Arduser—that you’re always better off suggesting something than stating something outright. Oblique is better than direct a lot of times. I like the idea of delivering images that are suggestive but leave some room for interpretation from the listener. I’m inviting listeners to ponder and contemplate what the lyrics are about, rather than clubbing them over the head with something that’s straightforward and obvious.

All the great songwriters I admire have mastered that, including Chris, Brian Lovely, and Rob Fetters. I owe them all an incalculable debt for showing me how it should be done. I try to emulate their approach in my own way.

What’s your take on the 2024 U.S. presidential election outcome and what it says about American society?

Even though I wrote these songs before the election, the subject matter reflects the moment we’re looking at. After the first Trump administration, it felt like something fundamentally had shifted in this country, culturally, economically, and socially. And despite the fact that Biden won in 2020, and there was a respite, the forces that created Trump had not gone away. And in fact, those forces probably became bigger than Trump himself.

So, as I was writing Sharna Pax’s debut record, those pathologies were present in my mind. It was clear we were not going back to what we imagined ourselves to be as a nation prior to 2016.

I wasn’t shocked by the outcome of the 2024 election. It seemed to confirm the essential feeling I had that this country has changed forever. In a sense, I was already writing about the outcome we got, because in a sense, that’s the world we have now.

What’s your perspective on the value of music in this era of polarization and chaos?

Music is a universal language. It’s the closest thing the global community has to Esperanto. Regardless of political or cultural orientations, music can bind people together. There are lots of musicians I’m good friends with that have political views that are very different from mine.

Sometimes I wonder if it’s just fantasy, but the truth is, I yearn for the days when politics weren’t so tribal. I wish we were still in the days when political agreements were merely over policy. I used to be able to argue with Republican friends amicably about the best way to provide health insurance for everybody, what foreign policy should be, or whether taxes should be higher or lower.

I’d like to think there’s a path back to rational discourse, somehow, in which we don’t see people who disagree with us politically as the enemy. I’m not terribly optimistic about this, particularly given how technologies such as AI are developing and being deployed via social media to really corrupt, spoil, and divide discourse.

But when we’re listening to music or performing it, there’s a shared humanity that we can reach for and experience, and I think it’s critically important.

Special thanks to Kevin McKeehan.