Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

Tu-Ner

Converging Circles

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 2024 Anil Prasad.

Tu-Ner: Pat Mastelotto, Trey Gunn, and Markus Reuter | Photo: Julia Hensley

Tu-Ner: Pat Mastelotto, Trey Gunn, and Markus Reuter | Photo: Julia Hensley

The careers of touch guitarists Trey Gunn and Markus Reuter, and drummer Pat Mastelotto have intersected and converged in myriad ways across the last 30 years.

Gunn and Mastelotto were both part of the 1993 Sylvian/Fripp band, which led to the duo joining the 1994-1999 King Crimson double-trio lineup. Gunn and Mastelotto continued performing together in subsequent incarnations of the ensemble until 2003, at which point Gunn departed. Mastelotto remained in further King Crimson formations between 2008 and its final live activity in 2021.

The musicians became close friends over the years and continue collaborating extensively across their own duo projects Rhythm Buddies and TU, as well as in their solo careers.

Reuter met Gunn and Mastelotto through shared musician circles between 1998-2000. In 2005, Reuter and Mastelotto formed the experimental instrumental duo, Tuner. The pair also worked together in The Crimson ProjeKct from 2011–2014. The six-piece featured musicians from across the King Crimson extended family focused on playing its double-trio repertoire.

Reuter and Mastelotto went on to create the ambitious, genre-bending Face recording in 2017, based on 385 bars of music woven together from more than 200 audio tracks. And they continue to be part of Stick Men, a group with Tony Levin formed in 2007.

In 2019, Reuter and Gunn partnered to helm Touch Guitar Circle seminars, which eventually evolved into duo shows. The musicians are also connected through their mutual experiences as part of Robert Fripp’s The League of Crafty Guitarists during the ‘80s and ‘90s.

It was practically inevitable Gunn, Mastelotto, and Reuter would combine forces. In 2023, it happened with the creation of Tu-Ner, which merged their duo projects into a trio.

The band’s just-released second album, Tu-Ner for Lovers, is a mercurial, improvised journey through many genres, forms, and moods. The record is based on material captured during its 2023 concerts. It shifts between art-rock realms, minimalist passages, spectral soundscapes, and abstract electronica.

Innerviews met up with Tu-Ner ahead of its May show at Sweetwater Music Hall in Mill Valley, CA to discuss the new album, its creative and collaborative process, and the collective history that informs its output.

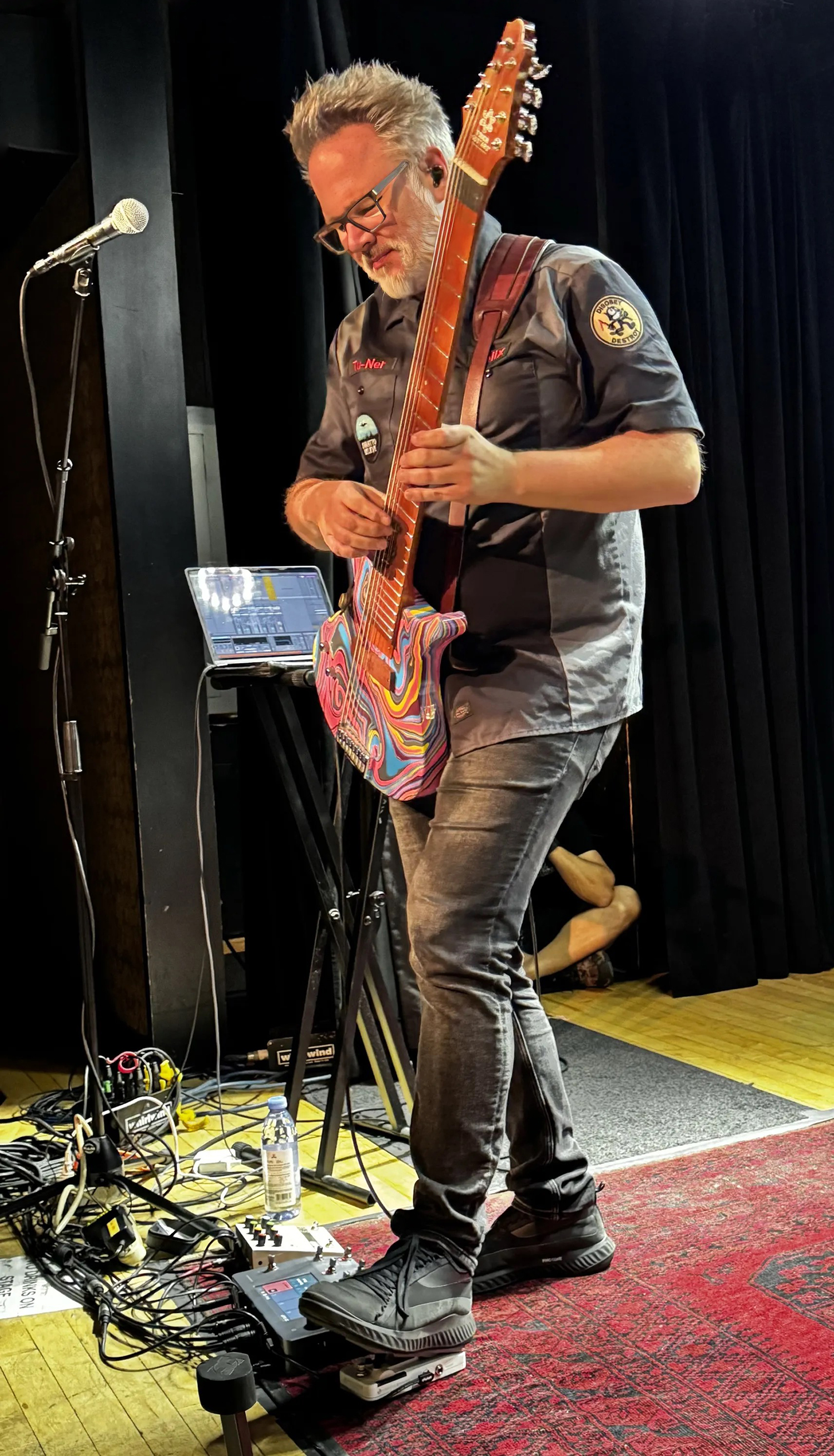

Photo: Anil Prasad

Photo: Anil Prasad

How did you arrive at the album title Tu-Ner for Lovers?

Gunn: For me, the inspiration was the John Coltrane record Coltrane for Lovers. That was it and we ran with it.

Reuter: Some of the titles are romantic movie titles, too.

Gunn: It’s not much deeper than that, except that the title is contradictory given the music is so obtusely abstract.

Mastelotto: After mixing one of the first pieces, "The White Thing," once we decided on Tu-Ner for Lovers as a title, I listened back to it with my wife Deborah. It was so abrasive. I said “It’s just so anti-love. What if we slowed it down?” So, we did that. Then we have the track "I Put a Crush on You" with the gamelan bells on it. That was the first track that did sound creamy and fit with the title.

Reuter: This is an album for music lovers. That’s my angle. You have to love music to love this record.

The album title also intimates the ideas of elevating and inspiring people. How does that connect to the complexities the world is facing?

Reuter: These times are giving us the freedom to do this kind of music in a more or less commercial context. The sort of division that exists also allows for radical expression. I think the Tu-Ner for Lovers album is pretty radical.

Mastelotto: Younger generations—people in their teens into their twenties—aren’t dating as much as they used to. It’s a disconnect compared to when we were teenagers. Now, I think a lot of them are playing video games and texting. They’re staying distanced. But I also meet older people who engage one-on-one with people on the ideologically-opposite side.

Live music is so important to people. When I started playing live right after the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe with O.R.k., it was incredible to have people crammed in small clubs again. My throat would choke up from seeing how much people loved to be back in these environments to hang, listen to loud music, and have a communal experience again. So, I think both the musicians and audiences appreciate it even more.

Gunn: It’s definitely a more precious experience since the pandemic.

You’ve all worked together in myriad permutations for decades. Talk about how you surprise each other and continue expanding your horizons.

Reuter: I think this band is developing its own character. It’s as interesting to me as when I saw Pat and Trey play together in 1993 with Sylvian/Fripp. In fact, I said “Let’s do a Sylvian/Fripp thing," so you’ll hear a nod to Sylvian/Fripp in the show. It’s a way of connecting the past to the future.

Mastelotto: We sometimes ask ourselves “Where can we pull from our catalog without being too obvious?” We couldn’t take a vocal tune from David Sylvian, so we grabbed the coda from Sylvian/Fripp's “Firepower” and used its coda as the coda for "The Construkction of Light" during the shows.

Gunn: There are also a lot of strange things we individually do on stage that undermine where you think you’re going. When we do improv, I have no idea what’s going to happen.

Reuter: The cool thing is there’s so much intuition with us that things just work. Any sort of expression one of us engages in finds its way into the fabric.

Mastelotto: Just changing one component means we’re completely different. Markus and I are also both in Stick Men with Tony Levin. In Tu-Ner we have Trey instead of Tony and that means there’s a different generation in the band with a different ethos.

Robert Fripp figured out the same thing in King Crimson. He realized if he changed the musicians around him, but he kept doing the same thing, the music is presented in a different way.

When we’re in improv mode, I’m clicking through my head about the options for where we can go, and the patches I can use. I’m also listening to these guys as this inner dialog is going on. Eventually something one of the other two plays will grab me and I’ll latch on to it. I’m also trying to provide them with something to latch on to.

It's funny. When we did ProjeKct Three, if Robert wasn’t enjoying something, I’d look over and he’d be filing his nails. And in ProjeKct Four, if Tony wasn’t into something, he’d put his hands in his pockets.

Gunn: It’s important not to leave somebody sitting there with their balls hanging out. But that doesn’t occur with us because we’re all just going forward and supporting each other in the music.

Reuter: An example of how it unfolds is I might play a random chord and Trey might play a random bass note, but somehow it all works, and we end up in a cohesive space together. It’s often more about the attitude than the actual notes.

Gunn: We know it’s always going to be okay.

Reuter: I’m actually using sounds sometimes that are completely detuned, so we have some quarter-tone stuff in the improvs. It’s similar to emulating broken tape.

Mastelotto: Sometimes I might introduce a patch that has a melodic element to it. I’m sometimes very nervous about it. I know I’m about to throw a tonality out there that could botch everybody else’s beautiful harmony. But I also realize that if you repeat it a couple of times, everyone’s ears go “Oh, this is okay.”

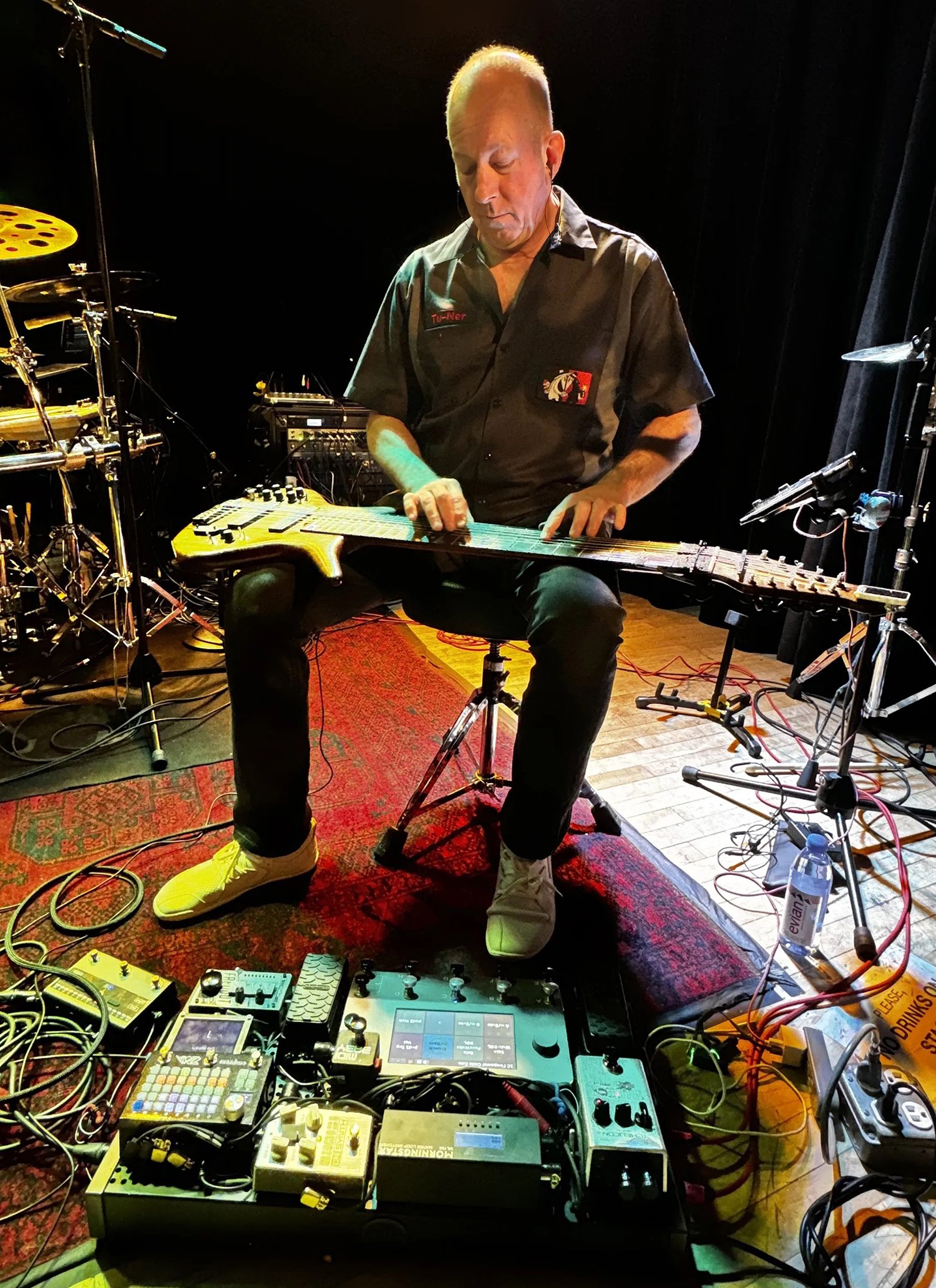

Photo: Anil Prasad

Photo: Anil Prasad

What are some of the other key considerations that create cohesion when you improvise? And how do you avoid going off the rails?

Mastelotto: We give each other cover between one place and another. We don’t want any dead air on stage, unless it's intentional. For instance, if someone needs time to change their patches, another one of us will ensure something’s happening.

Also, when you’re trying to do a cohesive show and you lose energy during an improv, it’s a drag. The other guys know if we experience that, I’ll want to scroll to find a new sound, and they’ll play something to help connect things together.

Gunn: We don’t look at it as the improvs going off the rails. I think if you look at it like that, you can’t get to the spaces we arrive at. We accept that any note we choose to play is going to be fine.

Mastelotto: In King Crimson, all the levels were loud. In this combo, I sought to be a quieter or softer drummer. You’ll hear what I mean when we start to play “The ConstruKction of Light.”

We added electronic drums to the group, and their dynamic range is way fun, but it requires a different approach to achieve that. I’m happy we added them, because there’s lots of potential for even more unique sounds.

Describe the art of editing improvisations into a final piece.

Reuter: The first Tu-Ner album, Contact Information, was recorded at Pat’s place, mostly live in the studio. One of the pieces was composed and there were a couple of overdubs, but mostly Pat did the editing of those pieces. He would decide “This is a piece” and then we gave it to Erik Emil Eskildsen to mix.

Mastelotto: All three of us really start pieces together from scratch. I was also the engineer for a few days. On the last day we had Bill Munyon come over to engineer so I could be at my drum kit. I couldn’t see Markus and Trey though, because they were set up in other rooms.

Some of the improvs were quite long and went up to 20 minutes. So, they got condensed. Also, sometimes the editing isn’t about chopping out parts or moving them elsewhere. It’s more like “Let’s get rid of this note and let’s mute this.”

I was always sending edits to Markus and Trey. We have a Dropbox folder where everyone can access the tracks and provide their comments. When things would go over to Erik, the same process would also occur. He’d condense things a little more.

Reuter: I’d work closely with Erik once it was time to be involved. We’d get Pat and Trey involved if there were bigger questions like discussing the drum mix. But this album was pretty painless. By the time we got to version two of a mix, it was usually finished.

Talk about the decision to make every track available to listeners as they were finished ahead of finalizing the album.

Gunn: The idea was to be able to tell the Tu-Ner for Lovers story over a longer period of time and also to give fans insight as things went along. We would change the mixes along the way sometimes. Some people got early mixes. When we got the whole thing finished, they got the newer mixes.

Reuter: I also did something similar in 2001 with Centrozoon’s The Cult Of: Bibbiboo album. We had a public mixing web page in which people could vote for their favorite mixes. So, it’s not a new idea. But as Trey said, it means the narrative of the story can be longer. The end of the story is when the record came out.

Markus and Trey, how do the two of you self-mediate your contributions in a live context to give each other space?

Gunn: There are compositions and then there are improvs. In the compositions, we decide who’s playing the low end. On the improvs, we do that in real time. Sometimes we’ll both play in the same space, too.

Reuter: One could say there’s no overlap or one could say we’re always overlapping. It’s about the character and the personality of the musicians. We have a good blend of people who know how to work together in any possible way. So, yes, sometimes we both play high parts or low parts.

Because it’s only three guys, we don’t have any traditional roles anyway. There might be no kick drum, bass, cymbals, or solos at any given moment. Everything is just another sound.

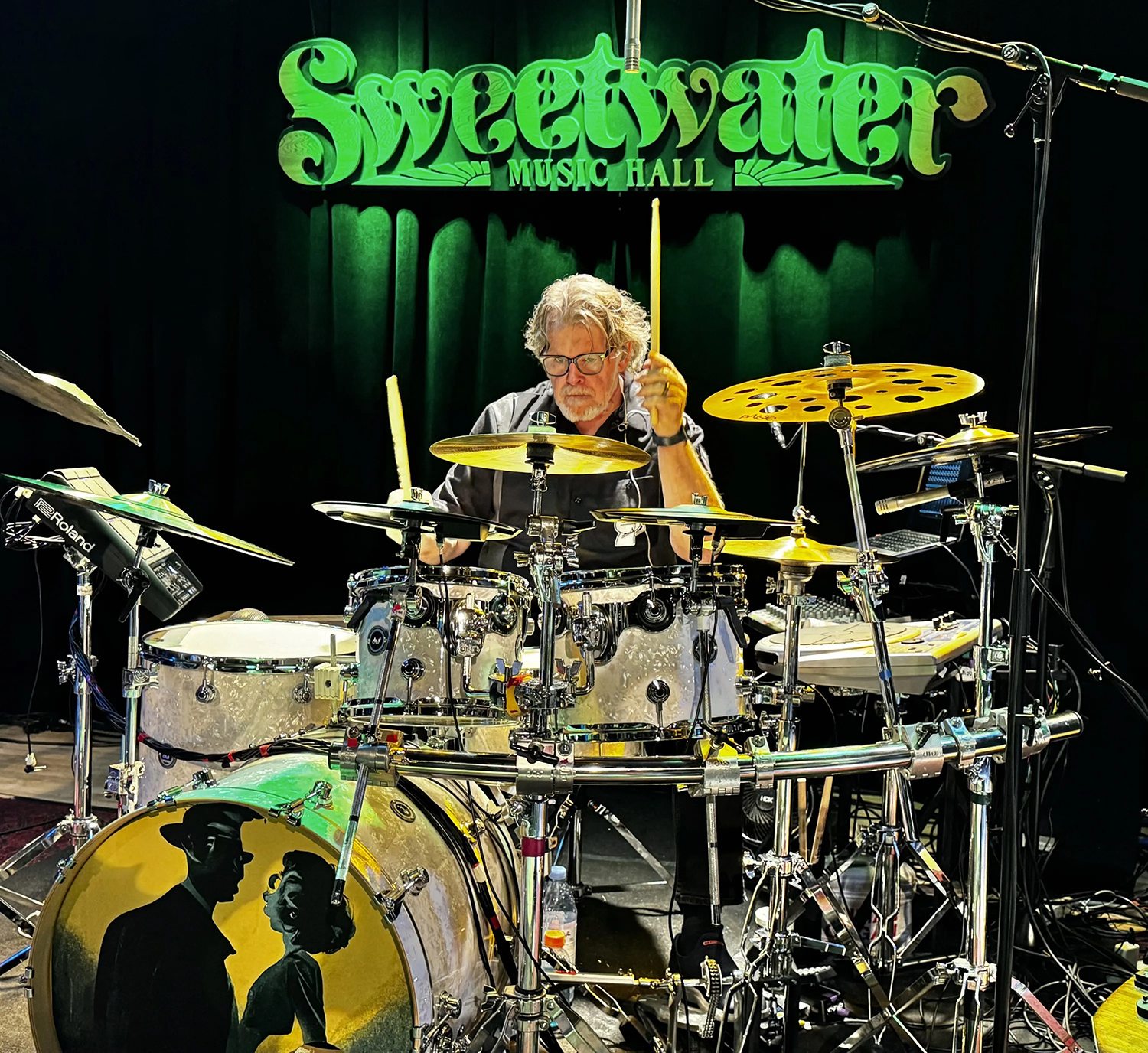

Photo: Anil Prasad

Photo: Anil Prasad

Pat, your role in Tu-Ner goes far beyond the realm of hitting things with sticks. Explore what else you’re doing on stage.

Mastelotto: I provide a rhythmic element, but Markus and Trey can both do that as well. I also provide an element of color—but they can both do that, too. So, how do you smear it all together? Things were mostly clear-cut when I was just one of three drummers in King Crimson in which I knew I had more of a rhythmic responsibility.

As Stravinsky once said, “I’m foraging for joy.”

Gunn: Pat is like a real-time sound designer.

Reuter: In Tu-Ner, he is really more like an orchestral percussionist. That’s how I see everything he does. When we did Crimson ProjeKct, I felt he was more somebody playing in the orchestra. He would be about attention to detail and when things would stop and come in.

Mastelotto: I have a Roland HandSonic digital percussion unit to my left that has a lot of good dynamics. It has synth sounds and they’ve all been tweaked. Sometimes people come up after the show and say, “I have that same box, but it doesn’t make any of those sounds.” I reply, “Well, I stay up late at night and process them, fuck them up, and store them.” I make a lot of pads. There are 15 playing zones on it. I can control sound sources, pitch, patches, and stereo placement. Sometimes I work with all of those at the same time.

The box on the other side of me is a sampling box. Sometimes things get a little messy, and I’ll go “Oh shit. I haven’t used that sound in ages. It’s over in patch 32, on the lower left pad. I hope that’s the right one and I can get to it before the moment is gone." But I do try to prepare things, so they have the right tempo at the right level.

Also, we’re mixing our own in-ear monitors from an iPad. Sometimes I might grab the wrong fader and turn the wrong guy up and down. Then I might panic and think, “Oh shit, I’m on another page here, but I’ve got to keep playing. How do I get to the right point? When will I have a one bar break so I can quickly fix things?"

If I was just using my acoustic drums, I’d be thinking the same way in terms of setting up sounds. There are opportunities to muffle the drums, to do more of a Ringo Starr thing, or put some metallic or wooden things on top of the drums. You can’t do those things with the electric drums I’m using with Tu-Ner. If you set something on top of them, they’re going to go boom. But so far, things have been working out well with my setup.

Markus and Trey, you both run record labels. Explore the challenges and rewards of pursuing those endeavors.

Gunn: 7D Media has been around long enough that we have enough of a vibe and when we release something, people give a shit. But in terms of the challenges, it’s accounting for me. Today, that’s just part of being a musician.

Reuter: The number of potential sales you can have has gone down so much. And even when I thought it couldn’t get any worse, two or three years ago, it did. Early last year, things started to go down drastically for Iapetus.

The best-sellers, such as Stick Men albums, will always do the same number. But it can be frustrating with the other music. My solution was to put out more music—not just stuff I make. There are more artists on the label now.

Gunn: With streaming, in fact, nobody has to buy anything anymore if they don’t want to. So, buying music is almost something between a donation and a vote of confidence in the artists.

Reuter: I agree. It’s exactly that: a donation.

Mastelotto: I think people of our generation still want to collect things. It’s why they want these souvenirs.

Both 7D Media and Iapetus are known for being transparent with the musicians you sign. Talk about the artist-first policy you both have.

Gunn: Part of the 7D model is that almost all the money goes out to the artists. But we also don’t invest our own money in the recordings. What does that mean? It means if you want to make a record for us, you’re paying for everything. I’m going to invest in my own records. Occasionally, we’ll invest a little bit in something we think is going to do really well if they don’t have the money. But we’ve figured out how to run a label as cheaply as possible.

We package the music, put it on a timeline correctly, get all the information together, and get it out. An artist can do that themselves, but if you don’t want to do that or want to be in alignment with our flow and audience, we’re great to work with. But we’re not for everyone. We’re definitely for mid-career artists who don’t want to do all of that themselves and see that they’re going to sell more with us.

Mastelotto: I’m one of the artists on Trey’s label. My wife Deborah and I put out A Romantic’s Guide to King Crimson on it, because it was easy, and he has a distribution channel.

Reuter: The actual curation is important. Our labels stand for a certain quality, sound, and the expectation we’ll deliver surprising stuff.

King Crimson during the 1994 Vrooom sessions: Tony Levin, Pat Mastelotto, Adrian Belew, Bill Bruford, Trey Gunn, and Robert Fripp | Photo: Tony Levin

King Crimson during the 1994 Vrooom sessions: Tony Levin, Pat Mastelotto, Adrian Belew, Bill Bruford, Trey Gunn, and Robert Fripp | Photo: Tony Levin

Pat and Trey, 30 years ago almost to the day, you were at Applehead Studios in Woodstock, NY recording the Vrooom EP, your debut output with King Crimson. How do you look back at that experience?

Mastelotto: There was confusion in the air and concern things might not end well. I remember Robert calling me and saying he sees the new band with me and Bill Bruford in it. I wondered “What does Bill think about this?”

Robert had a three-year plan for the band from the get-go. After recording at Applehead, we were going to Argentina to play, and then we were going to make an album at Real World Studios.

The thought was, “Let’s get comfortable with Bill before we commit to this.” So, Robert arranged for us to get together at Bill’s house. It was Robert, Trey, and me. Tony was there for one afternoon as well. We played together. I wouldn’t say Bill was happy, but he was very accepting about the whole situation, and we figured out what everyone would be doing.

At Applehead, things went very quick. We were there for perhaps two weeks. The first week we rehearsed, improvised, and worked up material. I think “Cage” was a tune Adrian brought in for the band. We also worked on another Adrian track called “I Remember How to Forget” that Robert didn’t connect with, so it ended up on Adrian’s solo album Op Zop Too Wah. The nail file came out for Robert with that one. It means he’s bored.

Gunn: That was really a thing. When the nail file came out, we always knew it was time to move on to something else.

Mastelotto: Robert was waiting for something he could shred over. I also remember Adrian’s equipment arriving, but it had been crushed during transport. It was a giant freezer-sized case with his David Bowie rig from the Sound and Vision tour. So, Adrian had to deal with getting it all back together, too.

I also remember the engineer David Bottrill arriving at the end of the first week. He was there to record what we had worked on the previous week. But he immediately needed a second tape machine and an extra chassis. The problem is there were too many mic inputs, and we weren’t set up for that. So, he was calling people in Manhattan to bring things over.

Finally, we’re ready to record. I start changing my drumheads and realize the guys are already overdubbing on what we were playing from the days before. So, I’m actually done and didn’t know. I didn't realize what I had played before was going to be used as takes.

And the other thing that happened is Adrian withdrew from the band after a few days during a meeting in the kitchen. He said, “Listen guys, this is fun, but it isn’t going to work for me. I have another career as a producer to focus on.” Robert responded, “Well, what do you need to make this work?” Adrian said, “I need three-to-six months a year to do my other projects.” Robert said, “That’s easy. We’ll give you six months a year.” So, the situation was resolved in the kitchen and then we were up and running.

Gunn: The only overdubs I did on Vrooom involved doubling the “Thrak” chords. Everything happened so quickly. I was kind of surprised some of those improvs made it on the release. Take “When I Say Stop, Continue” as an example. We didn’t have headphones on when making it, which is why it was called that. I had previously worked with Bottrill on the Sylvian/Fripp record. So, I was very comfortable working with him, but still it was intriguing.

Mastelotto: I have some other interesting memories from the studio kitchen. Mitchell Froom called me to say Crowded House needed a drummer right now. They wanted me to fly to Canada to join the last three dates of the tour. I couldn’t do it. Jeremy Stacey ended up doing it and he would go on to become a member of King Crimson later.

Also, during the Vrooom sessions, The Rembrandts’ manager called me to say they wanted me to play on the Friends theme song “I’ll Be There for You.” I had to tell them “I can’t do that.” I remember Danny Wilde from The Rembrandts calling King Crimson a bunch of old farts in response. But I said, “This music is me. I want to stay here.” So, I didn’t leave to cut the Friends theme. But I did recut it for them after I got home, and I played on the final version.

Gunn: Looking back, I like the version of “Vrooom” on this EP better than the one on the Thrak album. Same with “Sex Sleep Eat Drink Dream.”

Reuter: Everything on Vrooom is better than every other version. I still remember in 1991, when I had taken my level one Guitar Craft course, I had learned to play “Thrak.” And then it became a King Crimson piece. It was a raw, powerful version on that recording. I think you guys never matched that again, even in live performance.

Gunn: During my first Guitar Craft course in 1985, Robert showed us the “Thrak” chords. At a concert in Georgetown in Washington, DC, there were 18 of us playing guitar. Robert called out for “Thrak” to be performed and we started playing it. One by one, everyone fell out, except for Robert and me. It was just the two of us at the end of the piece.

Was that a signal that there was something more musically significant to pursue between you two in the future?

Gunn: I guess it was.

Photo: Anil Prasad

Photo: Anil Prasad

Pat and Trey, without your involvement in the Sylvian/Fripp band, none of us would be sitting together in this room. There would be no Tu-Ner, Stick Men, Crimson ProjeKct, Rhythm Buddies, or Face. Discuss how your tenure with the duo got put into motion.

Reuter: We met Bill Forth during this Tu-Ner tour. He’s a guitarist and composer who has known Robert for a long time. He’s actually responsible for the beginning of everything.

Mastelotto: We realized when we gave Bill a hug the other night that we wouldn’t be here without him. He’s the first domino.

Bill was how I found out about the audition for Sylvian/Fripp in 1993. I had put an ad in The LA Recycler about selling or trading a dbx 160 Compressor for $200. There was another ad in the same issue from a guy selling a Leslie cabinet for $200 or trade. So, I call the guy up and it’s Bill. I didn’t know him. I went over to his place, gave him my compressor, and took his Leslie cabinet.

He realized I was a drummer and I realized he was somehow connected to The Crafties, because he had some pictures of his work with them in his house. We had a good conversation. After I left, he called me an hour later and said, “You forgot to take the pedals.” So, he drove out to my house to drop them off. While he was there, he said “Oh, by the way, there’s this Sylvian/Fripp gig coming up and they’ve decided not to move forward with Jerry Marotta on drums.” I replied, “Who do I call?” He said, “I don’t know. I’m not connected with the management. The only person I know is Trey Gunn, who’s working with them.”

So, Bill gives me Trey’s number. I call Trey and he’s like “Dude, fuck off. I’m going to the airport right now. Today’s Friday. Auditions are in England on Monday. You’ll never make it. You’re wasting my time.” I said, “Dude, come on, help a brother out, just give me a number. Who’s the manager?” Trey replied, “Richard Chadwick from Opium Arts.”

I went and looked up Richard and found a phone number. I called him and said, “I’m this dude in Los Angeles. I hear these auditions are happening for Sylvian/Fripp. How can I take part?”

He said, “It’s useless. You won’t know the material. We’re not paying to bring you over here.” But I had heard a track on NPR the week before so I knew I could play the material. I knew some people at Virgin. I had already done XTC’s Oranges and Lemons, which was on the label. So, I asked someone there for an advance copy of the Sylvian/Fripp album. I drove to Beverly Hills where the offices were and got it.

It turned out after Richard hung up on me, he called me back shortly after. He must have called somebody at Virgin too and said, “Who is this guy?” Once he realized who I am, he said “Okay, if you learn a couple of songs and come over, you can audition.” So, I used all my frequent flier miles and booked a flight to England.

Before I went over, I went to Tower Records and bought every David Sylvian record I could find. Before that, Rain Tree Crow may have been the only record I had. I was concerned he’d want to do something from Gone to Earth or something else, so I felt like I should know in the back of my head what he’s talking about if he discusses his catalog. Also, I have to thank Bill once more, because he came by my place again and helped me figure out some elements of the music before I left.

So, I’m listening to all of Sylvian’s albums on the flight over. I also brought a trap case with as much gear as I could fit, including my snare drumhead.

Michael Giles was also up for the gig. He was coming out of retirement to audition. In fact, I think they originally thought he would be the guy.

Gunn: Michael was really fun to play with. He was a master. We rehearsed “Firepower” with him. As for Pat, I don’t think he knew that Jerry Marotta had overdubbed his cymbal sound in a different time signature for "God's Monkey” on The First Day. So, Pat was playing both parts because that’s how he heard it on the record.

Mastelotto: The audition was wild for me because it was at Real World Studios in a gazebo, not in the big room. Robert was in front of me, along with David and Trey. We played through a couple of songs and quite often they would fuck up. I’d say, “Guys, there’s a B section you’re forgetting.” I had been listening to The First Day 24/7 for three days before the audition, but they had done the record months ago. So, they didn’t remember the details.

I played for a half-hour. I knew they had another drummer coming. Robert set his guitar down while it was still looping and said, “I need to talk to you.” I thought “Okay, I’m going to get a rap on my knuckles for wasting his time.” But I see he’s writing a note. He said, “I don’t know what will happen with this gig. It’s up to David. But here’s my home number. If you ever need a recommendation, have them call me. Is there anything else I can do for you?” I said, “Can I get your autograph?” [laughs] And he autographed my snare drumhead. Robert then said, “Is there anything else?” I said, “Well, I heard Michael Giles is coming down today. He’s one of my heroes. I’d like to meet the guy face to face if possible and say “You were the guy. You were revolutionary to not just my world, but all sorts of players.” Robert said that was reasonable.

Eventually, in the distance, because Real World is in a valley, I saw Michael’s truck coming down over the hill. He didn’t use cases. He just put all the pieces of his kit in the back of the truck. He pulled in the driveway and there’s Michael. I said, “It’s a pleasure to meet you. This kid loves your work. Adios.” And I got a taxi and left.

After I got back to California, there was a voicemail from Richard waiting. My ex-wife Connie greeted me at the door crying, saying “They called.” I called Richard back, and he said “You’ve got the gig. Now we need to figure out money. We’re not cheap and you don’t seem greedy.” He offered a figure and I replied “perfect,” and he said “done.”

Photo: A.J. Chippero

Photo: A.J. Chippero

Everyone is in their fifties or sixties in the band. Talk about how you try to make the most of every moment as a musician.

Reuter: Things are difficult and strange in these times. Sometimes you have to do things that are hard and not fun or hard and a little fun. That’s how I see it. Of course, I enjoy things that are musically and artistically satisfying the most.

I don’t have the King Crimson label on me like Pat and Trey do, so it’s a little different for me. There’s something refreshingly free about that. I like doing something that’s fun and moves listeners and myself.

Mastelotto: And hopefully not lose money in the process.

Reuter: With Stick Men, Tony Levin brings in the audience. But musically, we can basically do anything we want. It doesn’t make a difference if there are 85, 155, or 185 people there. We’re playing the music we want to play, and Tu-Ner takes that to the next level.

Gunn: Every time I perform, I think to myself “Is this the last show I'll do?” I pay such a high cost physically with the time and stress involved in doing this. And you know, we might not be alive in three weeks.

Reuter: You never know if it’s the last time. Being aware of every single moment in which you have the pleasure of playing is a healthy thing to do.

Gunn: The truth is it doesn’t make any sense to tour at all. The amount of effort that goes into making merchandise, carrying the merchandise, parking the cars outside the venue, and still doing a soundcheck is a lot.

Reuter: Putin invading Ukraine made a difference in my approach and changed things for me. As a performer, I think I was always holding back a little, believing I would live forever. Then I realized with Berlin, where I live, being so close to Ukraine, that war could be very close. It was a trigger that changed something in me. Now, when I take the solo in “Level Five,” I’m just wailing, bending strings, going crazy, and being more expressive.

Gunn: You’re playing like they might be your last notes.

Reuter: Definitely. I’m more fearless than ever.

Special thanks to A.J. Chippero.