Donate to Innerviews

Since 1994, Innerviews has provided uncompromising, in-depth interviews with musicians across every genre imaginable. And it does that with no trackers, cookies, clickbait, or advertising.

Your donations are welcome to help continue its mission of highlighting incredible music and artists, without any commercial considerations.

Your contributions will be instantly transformed into stories and videos, and cover hosting and web management costs. Importantly, your dollars will help ensure Innerviews remains absolutely free to all visitors, independent of their ability to financially support it.

Please consider making a donation today by using the PayPal QR code below.

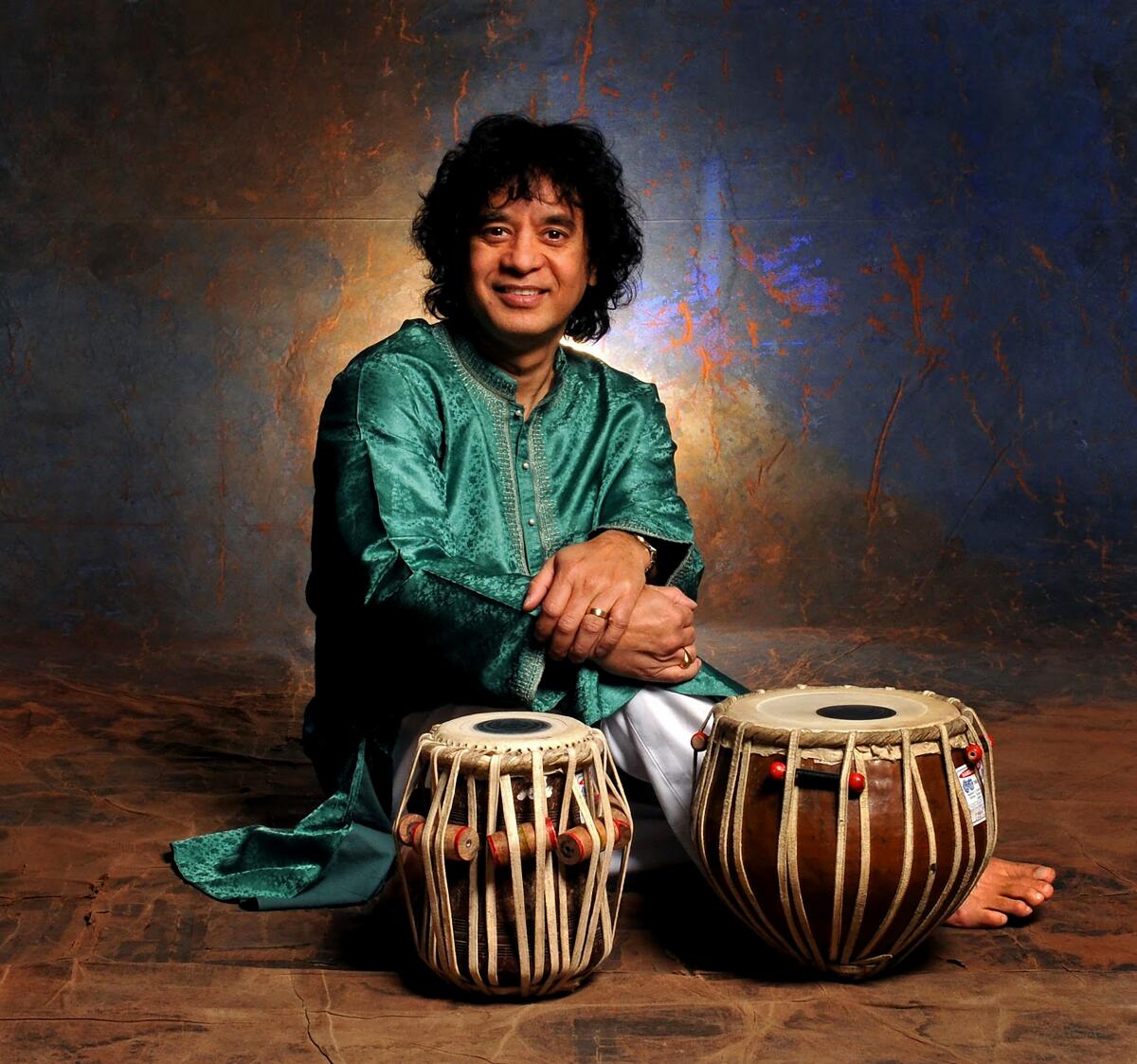

Zakir Hussain

In the Moment

by Anil Prasad

Copyright © 1999 Anil Prasad.

Photo: Jim McGuireWithout a doubt, Shakti’s East-meets-West explorations that bridged jazz and Indian classical music played a pivotal role in establishing world music as a viable, potent force. Formed in 1974, the groundbreaking group initially consisted of British guitarist John McLaughlin, North Indian tabla master Zakir Hussain, and violinist L. Shankar and ghatam player T.H. “Vikku” Vinayakram, both of whom hail from South India. The band, whose Hindi name translates as “creative intelligence, beauty and power,” fashioned an organic, fluid sound that combined what were then perceived as disparate traditions into a seamless whole. McLaughlin’s enormous fan base from his years fronting the wildly popular early '70s fusion group Mahavishnu Orchestra ensured Shakti had a large audience from the outset. As a result, it opened the ears of listeners worldwide to the immense possibilities cross-cultural musical collaborations can yield.

Photo: Jim McGuireWithout a doubt, Shakti’s East-meets-West explorations that bridged jazz and Indian classical music played a pivotal role in establishing world music as a viable, potent force. Formed in 1974, the groundbreaking group initially consisted of British guitarist John McLaughlin, North Indian tabla master Zakir Hussain, and violinist L. Shankar and ghatam player T.H. “Vikku” Vinayakram, both of whom hail from South India. The band, whose Hindi name translates as “creative intelligence, beauty and power,” fashioned an organic, fluid sound that combined what were then perceived as disparate traditions into a seamless whole. McLaughlin’s enormous fan base from his years fronting the wildly popular early '70s fusion group Mahavishnu Orchestra ensured Shakti had a large audience from the outset. As a result, it opened the ears of listeners worldwide to the immense possibilities cross-cultural musical collaborations can yield.

After a five-year, three-album run, Shakti disbanded in 1978. In 1997, the Arts Council of England contacted Hussain with the suggestion of reforming the band. It spurred him and McLaughlin to launch a reunion tour under the name Remember Shakti. The two remained friends and collaborators after the original group’s demise and even engaged in a brief Shakti tour of India in 1984. But the emergence of Remember Shakti marked the first significant activity invoking the band’s name in 20 years.

At the time, McLaughlin and Hussain were unable to locate Shankar and opted to recruit other co-conspirators. The 1997 concerts featured Vinayakram and North Indian bansuri player Hariprasad Chaurasia. The resulting 1999 CD, simply titled Remember Shakti, featured a complete gig from the tour. It was a very different effort from Shakti, Handful of Beauty and Natural Elements, the albums that comprise the group’s '70s output. Those recordings offered a fiery blend of acoustic pyrotechnics that showcased a youthful quartet determined to prove its mettle, as well as champion what was ostensibly a new musical genre. But for the Remember Shakti album, McLaughlin and Hussain preferred to let the music ebb and flow in a more restrained, meditative and traditional Indian manner.

Since the first Remember Shakti tours, Vinayakram’s son V. Selvaganesh has performed in place of his father on ghatam, kanjira and mridangam. Karnatic mandolin player U. Srinivas and vocalist Shankar Mahadevan have also joined, rounding out a revised quintet line-up. Still intact to this day, Remember Shakti has now been together longer than the original group.

Hussain’s expansive solo endeavors also continue with frequent Indian classical recordings, as well as relentless global touring. He also participates in the Indian electronica outfit Tabla Beat Science along with bassist/producer Bill Laswell, and the Global Drum Project, a percussion group that includes Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart, talking drum player Sikiru Adepoju and conguero Giovanni Hidalgo. On top of all that, Hussain runs Moment Records, an independent label devoted to the creation, distribution and promotion of traditional Indian music.

Photo: Paul Joseph

Photo: Paul Joseph

Why do you think there’s been such an enduring interest in Shakti’s music?

Why is there still an interest in The Beatles or Rolling Stones? There’s something magical about certain people coming together and linking on whole levels of communication, whether that’s through music, mind, heart, or emotions. Shakti was such a group that made that connection. You could see it when you watched the band play—the musicians were totally connected. They were operating as one. They were not four people, but one person. That brings incredible amounts of positive feelings and vibrations into one’s music and is something that lasts.

McLaughlin said the group was very dimly viewed upon its debut.

What happens is sometimes you have a vision and an urge to go forward and do something unique at a time when people are still tied to what is, as opposed to what should be or what can be. One must also realize that John had just disconnected himself from Mahavishnu Orchestra, a very, very commercially popular group. In many ways, John made the big sacrifice because he lost a lot of fans who were into his electric experience and they faded away. Another reason John probably said that is because the record companies and promotional outfits had no idea what to call Shakti, which category of music it fit into, or which bin in the record shop to put it in. So they looked at it with a great amount of hesitancy. But they’ve been proven wrong because Shakti has endured.

How much easier is it for Remember Shakti to operate now compared to the original group’s circumstances in 1974?

I think concert-goers have a much greater awareness of traditional music from all over the planet. It is more evident than ever before. The tastes of music listeners are so varied these days. They listen to everything from techno to rock to jazz to Indian to world to all kinds of stuff. It’s amazing to see people being so open-minded and panoramic in their vision these days. Therefore, a group like Shakti is just the ticket for a lot of people. The Remember Shakti record is doing well and the concerts are selling out wherever we play. The response has been so incredible. There’s great love and affection from the people to us. It’s incredible and amazing, even though this group does not resemble the old Shakti. It’s a different sort of group and in some ways a step forward to hopefully a next level of musical coordination and composition.

What impact do you believe Shakti had on other Indian musicians?

After Shakti, Indian musicians became much more open to the idea of trying things not only within the realms of Indian music, but by stepping out of Indian music and into any traditions they felt comfortable with. Shakti was one of the first combinations of musicians trying to do something that crossed all musical boundaries. We didn’t approach each other thinking “Okay, you play South Indian, I play North Indian and he’ll play jazz, then see what happens.” We just jumped into the wagon and took a ride together. It was four people as one. We were very young at that time and had no qualms about trying different things. We just sat down and played and did whatever was necessary to make it work musically and be fun. It was something unique at that time. Previously, when people from different cultures made music, one or the other music was crossing over and never meeting somewhere in between. For instance, if Yehudi Menuhin played with Ravi Shankar, Menuhin had to cross over into the Indian territory to play Indian classical music written for him by Shankar. It was never a combination of classical music and Indian classical music together. There were reasons for that. They were great traditionalists who believed they had to maintain their traditions.

Your father, tabla great Ustad Alla Rakha, wasn’t thrilled about your decision to join Shakti.

In the beginning, he did have problems with it. He felt I had to make my name as an Indian musician before anything else was to happen. As a teacher, he was worried that I would drift to the other side of the world and sever my connection with India. I convinced him that will not be and then proved that through my actions and it was fine. My deal with him was “Okay, I am going to play Indian classical music and I will travel to India regularly and play concerts there and have the audience accept me as an Indian classical musician. On my own time, I am going to do what I enjoy doing apart from Indian music.” Even now, 80 percent of the time I am performing Indian classical music. It is rare that I get involved in playing anything else.

Was his initial response surprising given that he had worked with Elvin Jones and Buddy Rich?

He had already proven himself as an Indian classical musician. He had been playing for 50-odd years and had already been accepted as one of the greats. So for him to interact with somebody posed no danger to him as far as losing his identity. For me, as a young musician of 19 or 20, there was more of a danger of that, but from the very beginning, my relationship with music other than Indian music has been adventurous. There was enough of a connection to my roots that there was little chance of me being overwhelmed by what I saw in the world. Therefore, I felt I could bend and work myself into any kind of music and play with any kind of people. For instance, when I work with Mickey Hart, he will try anything including throwing metal onto the ground and recording that or building a fire on a farm and putting a microphone there to record the crackling sound. He’ll also record a drum playing at one end of a tube with a mic at the other end 500 meters away to see what kind of a sound projection it has. It’s only by being open to all kinds of things and sometimes taking risks that you can really discover what is out there.

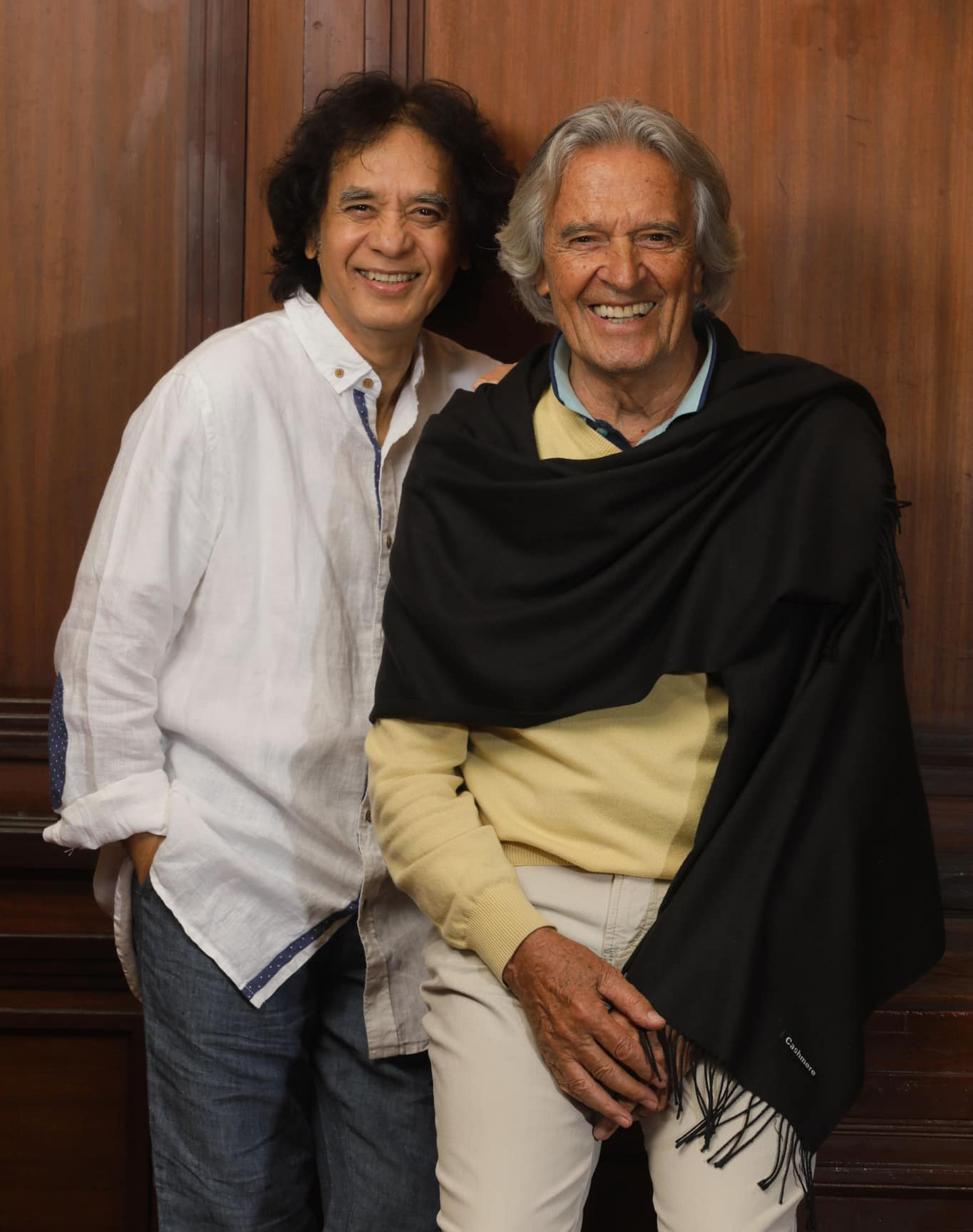

Zakir Hussain and John McLaughlin | Photo: John McLaughlin Collection

Zakir Hussain and John McLaughlin | Photo: John McLaughlin Collection

How has the chemistry between you and McLaughlin evolved over the years?

When I play with John, it’s not like playing with a Western musician. It’s like playing with an Indian musician, believe it or not. John has taken the time to study Indian classical music and figure out how we work, how we think and what our improvising techniques are. Myself, I have had the good fortune to study and understand the Western ways of musical thinking, be it jazz, pop or rock. In terms of musical interaction with John, it’s a bit more detailed now than before, but the same love and affection for one another is there. The fabulous thing is that connection hasn’t changed. I never feel like I’m working with someone strange from a different tradition and he doesn’t feel that way either.

Tabla is no longer the fringe instrument it once was. Today, it’s all over the place, including hit pop songs, television commercials and even hip-hop.

I’m elated. I’m happy that’s happened. Now I don’t have to explain to people what tabla is. That makes my job easier as a performer. People used to relate to India through the sound of the sitar. Now it’s not that. Now, it’s the sound of Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan’s voice or tabla. People know there is more to the sounds of India than just the sitar and that makes me feel really good. Somehow, it has reached the point where the sound is not only recognizable, but also in demand. There are some very, very fine tabla players now and a lot of well-known percussionists who play and really relate to this instrument. People like Trilok Gurtu, a fabulous jazz percussionist, have a lot to do with it. So has Talvin Singh lately. In my own way, I’ve contributed. It’s just an instrument that has caught on. It’s tabla’s turn at the moment.

Describe the motivation for creating your label Moment Records.

Moment Records wasn’t founded to do my music, but Indian music in general. When you do a record for any record company, you go to a studio, do the recording, deliver the tape, and then you see it in the store. Between the delivery of the tape and getting it in the store, musicians really have no say in what happens with the album cover, what’s in the liner notes or how the master mixdown sounds. I felt there needed to be a company that can provide a platform to Indian musicians so they can have control over what their product is like and have it appear simultaneously in all major record stores all over the world. However, it’s difficult to convince distributors and sales representatives to go out and sell our products in the shops and make them understand that they are worth putting in the bins. To a certain extent, my name helps sell them and makes it possible, but it is hard work and hard going. Today’s focus on world music and therefore on Indian music, means it is becoming a little easier.

What's at the center of your creative spirit?

Adventure, learning and finding out more. I’m still learning about Indian classical music. And every time I play with a new Indian classical musician, there’s more to learn. There are as many expressions as there are musicians, so it’s learning time no matter what. So, that is what I am—a student driven to make more and more discoveries.

Listen to the audio podcast version of the interview:

Connections:

Zakir Hussain

Shakti